When I was writing my last article about Instagram mental health comics largely being bullshit, one of my main resources was Instagram’s explore tab. As someone that loathes social media but adores hate-reading bad comics, it became (and still is) a new tool in my ever-increasing addiction. While I already wrote about the horrible mental health meme comics I came across, there is another genre that is just as awful but ten times more popular– the bad relationship meme comic.

This genre is significantly more vast and has a lot more variety than the mental health comics on Instagram. Because of this, there’s a wider range of quality in both art and writing. However, the majority of these comics share a common problem that has me asking the same question and again:

Where the hell are your friends?

These comics are drawn primarily by women, and the only characters shown are the author and her boyfriend. THAT’S IT. If they have a kid, then the kid’s always there too. It is a perfect microcosm of a societal issue that drives me bonkers — the message women get over, and over, and over — a man, and no one else, is the key to happiness.

I started looking around my feed. Out of the 300+ accounts I follow on Instagram, I really think that only around ten have done comics that focus on positive female friendships. Keep in mind most of these accounts are cartoonists that I genuinely respect and whose work I enjoy. Even an accomplished, prolific cartoonist like Lucy Knisley has an Instagram account full of comics about her husband and child and none about her friends, with the exception of 2018 and 2019’s hourlies.

I also wasn’t just looking for comics about female friendships either. What I was actually looking for was positive portrayals of female friendships — comics that celebrated good friendships. Not only is there a serious lack of female friendship portrayals in media in general, comics included, but when these friendships are shown, they are often a source of conflict and drama. When I told people I was thinking about doing this article, they mentioned This One Summer by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki. I hadn’t read it, but I knew the gist — kids growing up and growing apart. It was fine, but not what I had in mind. I want to highlight books that CELEBRATE awesome friendships.

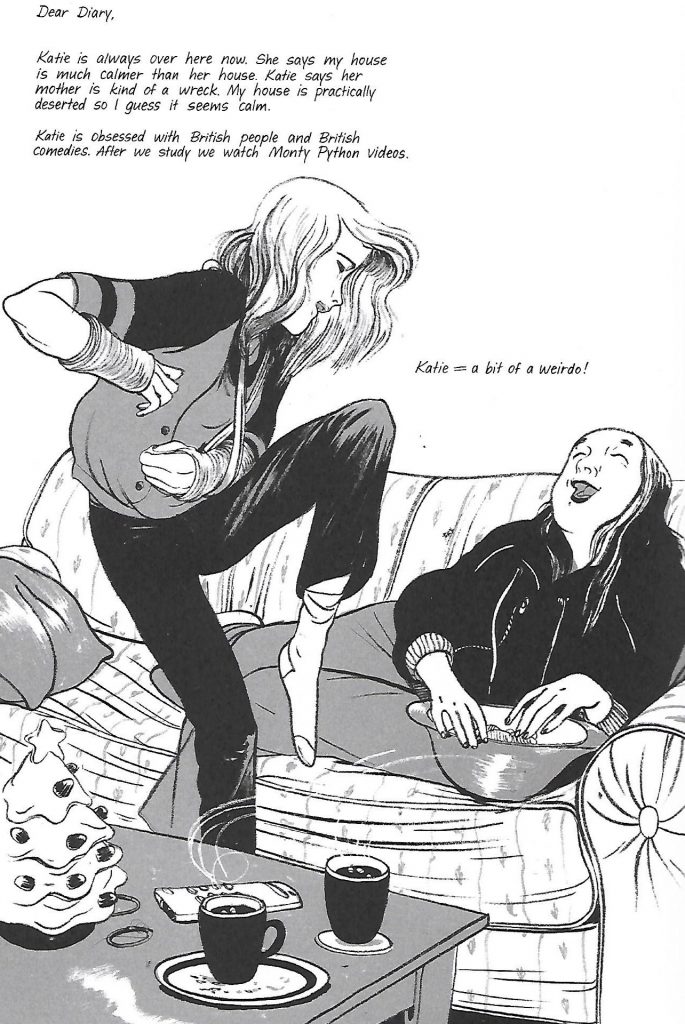

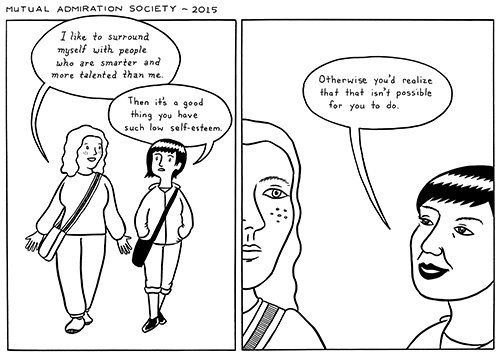

Only after reading This One Summer did it occur to me that Jillian and Mariko Tamaki’s previous book, Skim, was exactly what I was looking for. The beautiful thing about Skim is that while it is about growing up and drifting apart (among other things), it also shows how Skim survives and thrives by getting a friend she actually connects with and tossing out a toxic one. The friendship she ends up having with Katie is so strong because they are truly vulnerable with each other in a way they haven’t been with anyone else, and they connect about things like their shared trauma. Skim is such a brilliant book because it shows so many examples of truly selfish and misguided people attempting to help others they believe need it the most (in a condescending way) that the refuge two “at-risk” youths find in each other and the healing it brings is SO fucking satisfying. It’s also such a great use of cartooning. This panel towards the end of the book shows everything about Skim and Katie’s friendship:

Skim’s expression of pure joy in this panel at Katie’s antics shows: 1) the dynamic and strength of their connection and 2) how the friendship has helped heal Skim from the events of the rest of the book. She doesn’t have this type of happiness shown anywhere before this point in the book. Since I’ve experienced these types of friendships, I thought I’d highlight some other comics with female friendships that are worth celebrating.

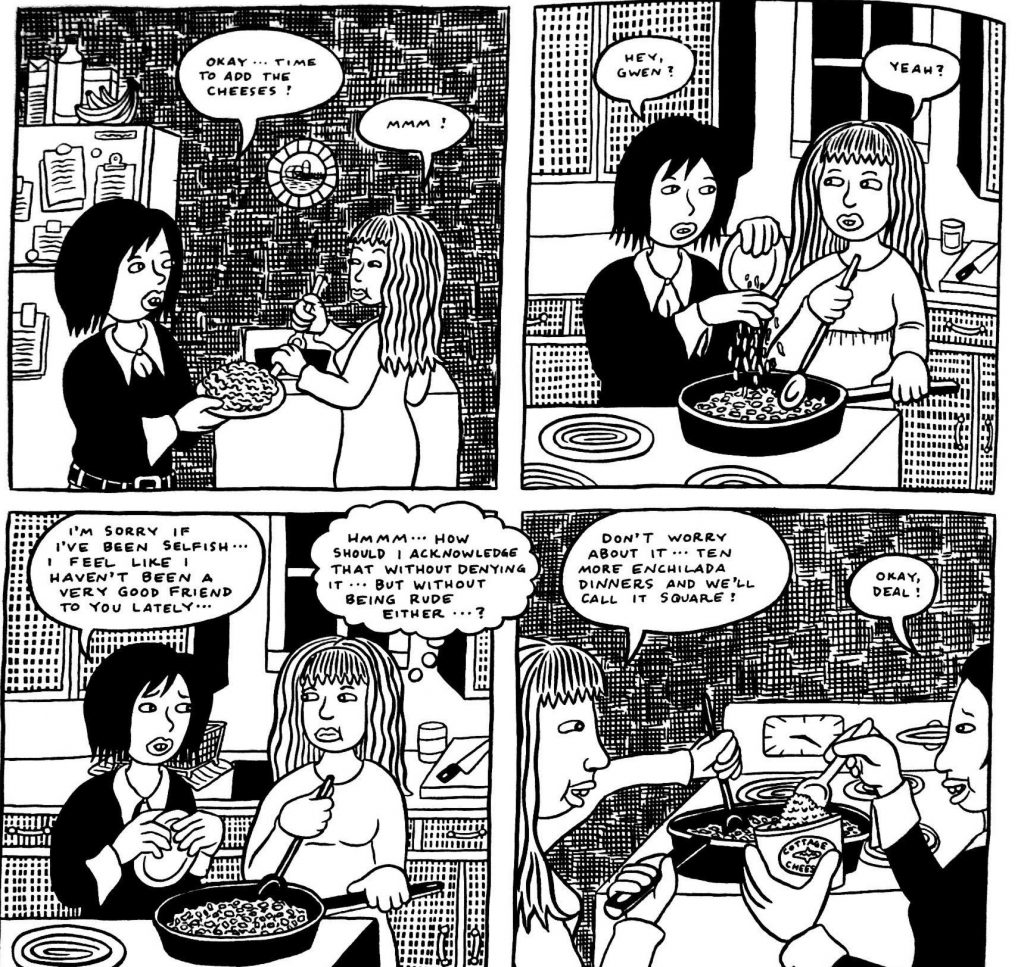

There were a few books in particular that came to mind when I really started thinking about this topic. I have already expressed my adoration for Ariel Bordeaux’s work in the interview I did with her. In No Love Lost, the narrator, Gwen, tells the story about her friend and the protagonist, Emma. She is recounting a story about a rift between them. Specifically, Emma is in a bad relationship that is dominating all of her free time and making her be a bad friend. Bordeaux talks about how she was very susceptible to the messages that the media puts out implying that women should prioritize men at the expense of everyone and everything else in their lives. I asked Bordeaux about her inspiration for making the book. She said, “So in this story, everyone around the main character, Emma, who was a stand-in for me, sees right through her – and she’s painted as kind of worse than I (like to think) she really is. I think what I was trying to do was to understand and own my own impact on the people around me.”

Bordeaux went on to tell me that the friendship depicted is strongly based on a toxic friendship of hers. While the real-life friendship between her and her friend fell apart, No Love Lost is what Bordeaux would have liked to have happened in an ideal world. “I was able to instantly gain some perspective on my own behavior, realize that maybe *I* was a little ‘toxic’ in some ways too, and talk it through with my friend,” said Bordeaux.

The thing I love in No Love Lost is that no one in it is portrayed as a bad person; Bordeaux gives all of her characters empathy and context. Even Jed, Emma’s bad boyfriend, is really a good guy. They just don’t suit each other. Emma is a bad friend and apologizes for it. Gwen accepts the apology without letting Emma’s poor behavior slide. When I read Gwen’s thought process as a middle schooler — both holding her accountable while being polite about it — it had a positive impact on how I deal with my friends today. It’s something I’ve never really seen in other work, especially at the time. A major reason for that is because it is shown by female characters in a thoroughly female voice. Both of the characters’ internal and external dialogue resonates with how I experience life as a woman and how I interact with other women in the day-to-day. And the fact that it had such an impact on me shows, in my opinion, that it is exceptional and more comics should portray this kind of narrative.

To me, the fact that No Love Lost is so obscure is tragic because of the power of Bordeaux’s strong, authentically female voice. This is in opposition to Daniel Clowes’ much beloved and celebrated Ghost World, which is many people’s go-to example of female friendship in the 90s. Ghost World is about a pair of teenage friends straight out of high school trying to figure out any sense of direction for their future or purpose while being contemptuous of virtually everyone else in their town. I absolutely hate this book. There are a number of reasons. One is that I don’t think Gen X cynicism holds up very well 30 years later. Also, the characters are thoroughly unlikeable. When I was told that Enid is a stand-in for Clowes himself, I wasn’t surprised because Enid and Rebecca are just teenage boys in girl’s clothing. Their entire dynamic of not only ripping on each other, but the amount of vitriol involved just reads like a work by an author who has no idea what teenage girls are actually like. Women can be cruel to each other, but it’s a totally different and more nuanced vibe than just constantly calling each other slurs. Rebecca has some moments where she is sympathetic because she is aimless the way a lot of high schoolers are after graduating, and her having to play second fiddle to a better-liked best friend resonates with me. Enid also dismisses Rebecca’s pain quite often because Rebecca is pretty. This is in line with the cultural narrative that being an attractive woman guarantees happiness, and the fact that Enid feeds into this is true of many teenage girls. However, it also shows that she is not a good friend when Rebecca is literally expressing her pain throughout the book.

Also, having Rebecca want to come along with Enid to college because she feels like she has nowhere else to go is well done too. But I cannot really understand why Enid is liked by anyone, period, yet everyone seems to be enamored with her. And her self-loathing isn’t really explored enough to have the ending actually feel satisfying. The real problem here isn’t the comic itself, as much as that when I tell people I want to do this article focusing on positive portrayals of female friendships, they give me books like this — a story 1) with women that feel fake and 2) the fact that this isn’t positive in any way — it’s a story about a friendship falling apart and the pain surrounding it.

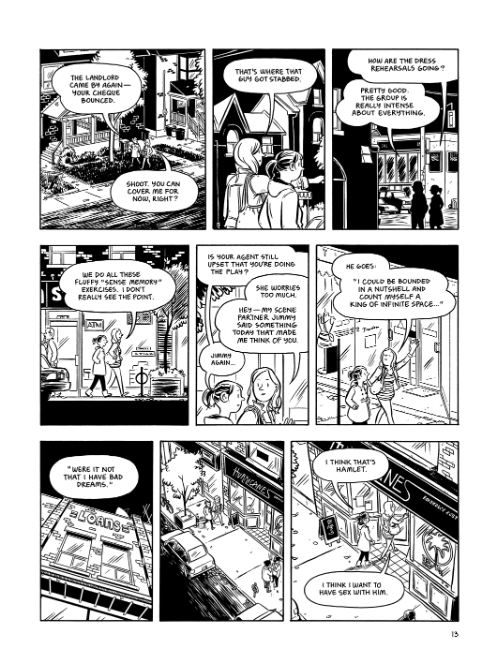

A great rebuttal to this is Young Frances by Hartley Lin. This book takes so many toxic Hollywood tropes and turns them on their head. Frances, the protagonist, is the mousy best friend to Vickie, an up-and-coming actress that is beloved in NYC and ends up getting a role in Hollywood. While Vickie is starting her dream career, Frances is stuck in a very stressful job at a law firm and is thinking of leaving. Vickie is introduced as seemingly self-centered, flakey, and not really caring about Frances. One of the subversions of this book is actually once she is settled in Hollywood, you see that she actually is a wonderful, caring, and unbelievably supportive best friend. She was acting like a stereotype of an actress in large part because she was making her dream come true with all of the excitement and stress that entails. Overall, the book is so satisfying because Frances finds her own way to be happy that is not the typical Hollywood narrative of escaping the grind of a normal life and following her dreams. Even though her best friend is across the country, Vickie goes to Frances as a major source of love and support while she is figuring out her life.

While I believe that giving women the space to write about themselves is crucially important, I think that men are completely capable of writing convincing and interesting women. Young Frances is one example of that. Another is cartoonist Zack Bly, who I only noticed after re-reading all of the zines I’ve collected of his over the years that predominantly have female leads. His work is funny and lighthearted in a way that most of the comics on this list aren’t, but you are still just as engaged with the characters. He also draws heavily from his background when writing his characters, regardless of their gender. He, unlike Clowes, does more than portray himself as a teenage girl. When I spoke with him, Zack Bly mentioned that when creating characters, he draws from his experiences and meshes them with women in his life he respects: his friends, his wife, and the women with whom he works (Bly’s career had been primarily in public libraries and non-profits, both women-dominated fields).

Bly also said that he is influenced by the books he reads, many of which are recommended by his wife with a degree in gender studies:

“One book that I’ve thought about maybe once a week for the past eight years is You Just Don’t Understand by Dr. Deborah Tannen. Reading it showed me patterns and styles of communication that our society typically genders as male and female. For example, people who use male communication styles tend to view relationships in terms of hierarchies, while people who use female communication styles see them as networks, or webs. Obviously, it’s a huge generalization, and I’m probably not doing the best job of explaining it, but it all has to do with the kinds of expectations that were placed on you and role models you had when you were young. It’s put me on the lookout for behaviors that fall into those patterns, in myself and others. Once you learn to see them you start finding them everywhere. Like for instance, I never read a Baby Sitters Club book until I was an adult, but when I did, it was so obvious that it was not written for people who see relationships as hierarchies—how many book series for boys are there that deal so forthrightly about jealousy, envy, shifting alliances between groups of friends, betrayal, misunderstandings, and forgiveness? The books that were available to me as a boy were largely about surviving in the wilderness or fighting with ghosts or spaceships or stuff like that. Or if they were more grounded in relationships, it would be about running away from home or hating your dad or something. Nothing like the emotional complexity of The Truth about Stacey.”

This is something that all of the works here highlight — the lack of hierarchies. With Skim, her toxic friend who she has a falling out with is in charge of the two, and their falling out is largely due to Skim growing and standing up for herself. This is also the exact trope that Young Frances subverts — you think Vickie is a figure whose shadow Frances has to step out of, but they are in fact equal partners in their friendship.

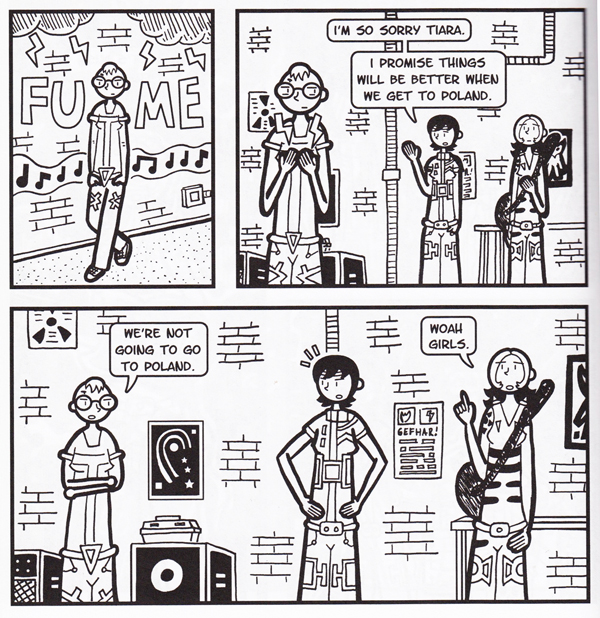

Another male cartoonist that I think writes women very effectively is Robin Enrico. I stumbled upon his work in high school. His flagship series, Jam In The Band, focuses on a musical riot girl trio and their friends. It’s about a lot of band drama, mostly stemming from every band member’s differing life goals. What I really like about the work is that all of the characters have different personalities, dreams, and motivations, and the way they interact feels real to me. And with Enrico’s work, you get a mix of female dynamics, even with the same characters. Bianca and Tiara are not friends, even if it is not recognized by the people around them, because Bianca railroads Tiara’s feelings every time they interfere with Bianca’s ambitions. The same can be said with Bianca and Corbin, to a lesser degree in this series, because Corbin is more outspoken. Bianca is a solitary figure because she lets her ambition get in the way of forming deep connections with anyone. Corbin has multiple friendships where both parties are equal, though the relationships themselves are very different. The friendship between Becky Vice and Corbin vs Corbin and Jennet are nothing like each other — Becky Vice and Corbin are pals whose initial gravitation towards high octane party situations is what bonded them, though their friendship deepens over time.

The relationship I have the most affection for is Corbin and Jennet. Their relationship starts with Corbin, a very sexually driven lesbian, pursuing Jennet, a quiet, heterosexual artist. They end up having a platonic coupling that I really adore — they find their own way to love each other and find a good life for themselves. I asked Enrico specifically about this relationship. He said, “Corbin and Jennet in Jam in the Band, and especially as they carry over into Things Between are the characters who get to get out okay. Not the norm, but a good life, good enough. I feel like hard-won platonic love is something that’s not really explored much in fiction, but it’s something that’s been a major thread in my actual life. It also feels like a good middle ground between my characters who find their place in ritual society and those like Bianca or Becky, or Leona are too off-model to ever really find a home in this world. Me writing Corbin and Jennet is again me trying to imagine a more hopeful outcome. I’ve never had much in the way of role models for the kind of adult relationships I wanted. I suppose that’s why I had to write some for myself.”

Robin Enrico is a cis man but writes primarily about female characters. His identity plays into how he writes women in his work. I asked him why he writes about women when he doesn’t identify as one. “I write about women, but I don’t think I could ever write about what it means to be AFAB or to exist in a female body. I write predominantly about myself (sides of myself) and somewhat about my friends. But I have only the most through a glass darkly idea of what it means to be a man and a forever at a remote idea of what it means to be a woman. I do know feeling like you’re on the outside, not wanting to do what everyone else has always done, and I sure know screwing your life up because of things you think you want. I’ve been around long enough to know that feelings like that are in no way confined to any one identity.”

The primary reason Enrico writes mostly about women mirrors Bordeaux’s reason for gaining perspective on himself while telling his stories.

Enrico says, “Making my protagonists women is a very conscious choice on my part. The reasons however are complex. On a surface level it was a means of abstraction, of obfuscation. Even when I am introducing supernatural elements into my stories, they are at their core about my experience. …In taking steps to separate myself from my protagonists it allows me to examine myself from the outside. Writing Bianca as stubborn and egotistical lets me try to understand the parts of myself that are the same without immediately putting up my defenses, because I’m not exactly talking about myself. And this is only my perspective, but for the stories I am trying to tell, interior stories, it just feels more correct to have a female protagonist. There’s so much baggage of accumulated male protagonists in fiction, that I feel like I would have to work doubly hard to make one not feel out of place within what I am trying to do.”

Both Bordeaux and Enrico give themselves the space to explore parts of themselves they dislike but in different ways — Bordeaux has a supportive friend narrate her stand-in, Enrico changes the gender of his. However, with the strongest friendships shown in both of their stories, it’s what they want to see in their own lives as well.

In a similar vein, the large cast of characters in these works brings to mind a comic I really enjoy by Caroline Cash, Girl In The World. In it, you see a group of girls who all have different experiences on the same evening, but, in the end, get together to hang out. It really encapsulates the need you feel as a young adult to cram as much fun as possible into a weekend. The girls in the book have a wide variety of experiences women can have on any given night — from a laid back night watching America’s Next Top Model and getting high, to getting out of a psych ward and grabbing McDonalds, to going around spraying graffiti, to narrowly avoiding getting attacked by a skinhead. But, in the end, the women all get together and find comfort in each other’s company.

When asking Cash about her inspiration for creating the book, she said, “The main motivation behind making Girl in the World was trying to make a book that I would want to read, about characters that reminded me of myself and my friends. Something fun to read that you know, had a plot behind the weed jokes. My nights out always kind of were all over the place, and I knew my friends had similar times running around the city trying to cram a ton of stuff into the weekend. What seemed most important to me was that, no matter how busy it seemed, we’d usually end up together in one way or another.” This comic is short and you only get a superficial look at the characters, but you still see an important aspect of friendship that reminds me of Becky Vice and Corbin from Jam in the Band. These girls like hanging out, they like partying, they like getting high. But they are also each other’s source of support and comfort. They come together at the end of their adventures and end their day with the people they enjoy spending their time with the most.

The differing types of dynamics between friends in Enrico’s and Cash’s work is similar to one of my favorite webcomics of all time: Girls With Slingshots (GWS) by Danielle Corsetto. GWS is a daily slice of life webcomic that ran for 10 years (!) and follows Hazel and her core group of friends through their day-to-day lives. Here you get the deepest exploration of characters. One of the main reasons for that is the length (it updated 5 times a week for 10 years), but another is it became the focus and heart of the story. There are so many webcomics that started in the early 00s, along with GWS, that totally shift gears in a disorienting and jarring way or reboot completely. This is usually because the creators are so focused on narrating the actions of characters versus having the characters feel so real that they seem to take over the show. When I was invited to participate in the Our Comics Ourselves project run by Jan Descartes and Monica McKelvey Johnson, I highlighted GWS for having one of my favorite endings of any comic series ever. Everyone in the cast gets a unique happy ending versus the standard uniform ending a lot of media pushes on women where the female lead gets married with the promised future of popping out children (obviously every woman’s deepest desire). Even beloved progressive comics created by women are guilty of this, such as Octopus Pie.

While I will not spoil the ending of GWS here, what I will say is that the ending, while satisfying, is open-ended so that Corsetto can revisit the series in the future if she wants to. Like Enrico’s comics, GWS has a fully realized and delightful cast of characters, both male and female, with separate dynamics between all of them (including a non-sexual romantic coupling between Jaime and Erin, similar to Jennete and Corbin’s relationship). Unlike the diversity in everyone’s happy ending, there is a shocking amount of consistency in how all of the women became friends. Corsetto told me that she enjoys fiery and icy relationships, and most of the strong bonds at the beginning of virtually all of the friendships formed by the female cast start with them being antagonistic and fighting. Jaime, the kindest and most caring member of the group, is the one that ends up connecting and bringing former foes together through her “Pussy Club,” where the girls get together and talk about being women while drinking. Eventually, the group becomes friends so the club moniker is dropped, but their grouping still serves the same purpose. Jaime starts out more aggressive in the beginning of the series, and is similar to the salty protagonist Hazel, but becomes more realized as the strip progresses. This is largely due to the story being created over the course of a decade and Corsetto coming into her own as a writer.

One of Corsetto’s greatest achievements in writing GWS is the friendship of Candy and Clarice. Candy has been in love with the town barista Jameson for years, who starts out single but falls in love with the sweet and timid Maureen. Hazel is at one point in love with Jameson and hates Maureen as well. However, Hazel reacts properly when Jameson makes it clear that he sees Hazel as a friend only, and her being hostile to Maureen, the love of his life, is completely unacceptable. Candy doesn’t accept his boundaries and in one arc makes a grand production of trying to ruin Jameson’s and Maureen’s wedding. She is, rightfully, ostracised by the rest of the group. While in a lesser cartoonist’s work Candy could be a universally reviled character, in GWS she has a good friendship with Clarice, who, while giving her shit about her actions, continues to be a caring friend. While their relationship goes through ups and downs, they remain friends. Like Emma in Bordeaux’s work, Candi, while worse than anyone in No Love Lost, isn’t universally bad or evil. Both Corsetto and Bordeaux give context and empathy to even their most problematic characters.

One of the strengths of multiple authors I interviewed for this piece, including Corsetto, is that they show not only strong friendships between women, but different types of friendships. While the main reason I get angry at the portrayal of female dynamics in media is because it is often so negative, another issue is that the types of bonds depicted are so narrow, even the positive ones. Corsetto and Enrico have a real knack for showing how a woman can have meaningful friendships with multiple people and they’re all unique.

The transformation of Clarice, Hazel, and Maureen’s friendships from hateful to deeply loving is similar to the transformations found in MariNaomi’s autobio short comic I Thought You Hated Me. This short graphic memoir is about the decades-long friendship developed between MariNaomi and her friend Mirabai. You see Mirabai starting out as MariNaomi’s bully, then becoming her close friend as a teen, them losing touch for years in big part over a misunderstanding where they assumed the other one hated each other (hence the title of the book), and finally becoming extremely close as adults.

I asked MariNaomi about it, specifically in terms of why she chose this topic. She responded, “The idea of this book was born when Retrofit approached me and asked if I wanted to publish a book with them — any subject I wanted. That’s a dream gig, if you ask me, the total freedom. Immediately I knew I wanted to write about female friendship, as that’s a subject I find not only sorely lacking in U.S. art and media, but also not-reflective-of-my-experience-at-all when the subject is broached. Whenever you see female friendships in movies, for example, there’s so much acrimony, usually involving fighting over some guy. So many things are male-centric, even when it’s supposedly focused on women!”

Unlike the previous work mentioned, I Thought You Hated Me is straight-up autobio and MariNaomi is relating real events from their relationship. For me, this brought up issues about consent. As an autobio cartoonist myself, I think it is incredibly selfish to not get proper consent from people in your work, especially those who you love. MariNaomi responded saying, “It made sense for me to write about ‘Mirabai,’ as our relationship has been pretty interesting over the years, a lot of ups and downs. I immediately asked if she’d mind if I wrote about her. I think she felt pretty weird about it, but I let her see each draft, and I gave her veto power, in case I crossed any lines or gave away her secrets. I don’t recall her vetoing anything, but she did say she remembered things differently than I. I’ve been encouraging her to write her own book as a companion piece, to tell her side of the story. I think she wants to, and I’m bracing myself for her book being way better than mine. 🙂 “

An aspect I really love about I Thought You Hated Me is showing the transformation of a female friendship over time, told through a series of moments. It’s a unique format that leads to insight about a friendship lasting decades. This is something you don’t often get to experience in media: how female characters’ friendships go through changes and improve. You also rarely get to see comics about women older than their early 20s discussed at all, especially a few years ago. Even now, middle-aged women’s comics are usually about overcoming negative experiences (breast cancer or losing loved ones are what immediately come to mind). Mirabai started out bullying MariNaomi, then pretending to like her, and then they finally became real friends. There are a number of instances in this series that I relate to, including Mari’s insecurity about their friendship. As she says, “I’m not sure I will ever feel entirely secure in any of my relationships, even this one. Nothing is permanent, whether you drift away from a person, you disconnect purposefully, or you’re separated by death or circumstance. But regardless of what happens, I know that our love is true, that our relationship has been significant to one another. I’ve known this since we were teenagers, probably around the time she took the photos of me, which is why I was surprised and hurt when I thought she separated from me on purpose.”

One of the reasons I have chosen the included comics in this article is because I find the ways the friendships highlighted are strong because of good communication. Specifically, the reason I chose these works is that they all read as authentically female, either because the author is a woman or is a man with a lot of women they love and respect in their lives that they actually listen to.

As Bly mentioned, the book You Just Don’t Understand by Dr. Deborah Tannen explores how men and women communicate differently. Examples of women communicating well with each other are rarely portrayed. The benefit of watching a decades-old friendship portrayed over the course of a book is that you see not only the characters change, but the communication between them maturing as well, strengthening the friendship overall. When I asked Mari about this, she said, “Gah, this is the thing we’ve all got to learn at some point, isn’t it? How to communicate, how to see through other people’s eyes, how to be compassionate, less selfish. My experiences with Mirabai in that arena have certainly taught me some lessons about communication and that I shouldn’t make assumptions about people. Even now! I will be attempting to learn these lessons until I die.”

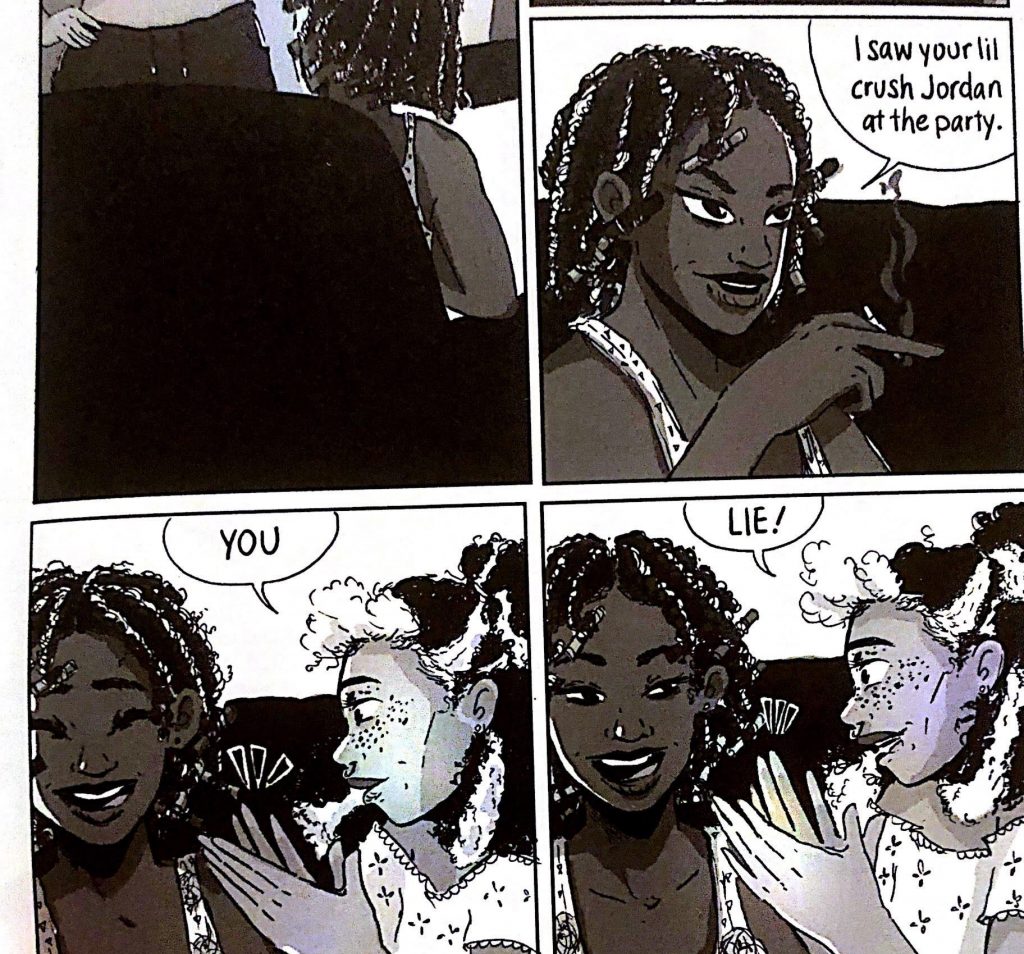

Continuing this idea, another short comic zine that shows multiple ways of communicating love and affection between friends (along with the characters’ daily lives ) is Wash Day by Robyn Smith and Jamila Rowser. It shows the protagonist, Kim, taking care of her hair, buying her friend Cookie a sandwich, and them catching up. The power of this comic comes from how authentic and intimate all of the events are. The friendship between Kim and Cookie, just like everything else in the book, feels very real and very personal. This panel below is the perfect encapsulation of their dynamic.

I asked the artist, Robyn Smith, about how she and author Jamila Rowser collaborated on the comic: “The script was so detailed, I feel like Jamila Rowser (the writer) has mastered the art of writing a comic book script. So much of the movement and the environment is described in great detail. Basically to the point where I understood it almost as a play. Jamila also had a very set vision for this comic and conveyed that idea very clearly by gathering her own reference material.” This included things like character mood boards. I have been a huge fan of Smith’s since we went to the Center For Cartoon Studies together. The panel above stood out to me because I have experienced this exact thing with my friends, yet I’d never seen it in comics before. The second I saw it I knew the pacing was Smith’s decision. As she said, “One thing I pride myself on is pacing, so there were a few moments I slowed the book down but apart from actually drawing the book, that was mostly my input when it came to mapping out the pages. So in the end I think the narrative imagery came mostly from Jamila’s script but talking about how we’d push the story along with each panel was highly collaborative.”

Many of the comics here show multiple forms of communication between a pair of friends. Not all forms of communicating love for friends are through verbal discussion. To me, the simplest and most effective use of non-verbal communication of love in terms of a narrative device is Kim buying Cookie a breakfast sandwich in order to show her love for her, but also so we can explore the rapidly gentrifying NYC as Kim sees it. The fact that this mini says so much, and that you really get to know Kim and Cookie in so few pages, shows why the zine was so successful. As Smith says, “The authentic nature of the way Black women can relate to and trust each other is something Jamila and I know well, so of course incorporating that into Wash Day just comes naturally. Add the layer of Black hair care to it and it becomes something even more intimate. We are at ease knowing Kim’s well, her hair is done and we experience the comfort of her friendship with Cookie.” Wash Day’s brilliance comes from the fact that you are getting an intimate look at Cookie and Kim.

The last cartoonist I interviewed for this essay is an autobio cartoonist named Athena Naylor. Like MariNaomi, Naylor makes comics about herself and her friends, though they are done in real-time, so there isn’t an arc of their friendship evolving like in I Thought You Hated Me. In my opinion, Naylor’s friendships are portrayed the most powerfully of any listed in this essay. Naylor’s work shows the intimacy between herself and her friends that I have never seen anywhere else. She is also willing to be vulnerable in a way that is incredibly rare not only in comics but I would say in art in general. Her relationship with her friend Rachel is the epitome of this. Like all of the works listed, Rachel and Naylor’s friendship is built on good communication. They have their own rituals, dynamics, and languages. Naylor explores them more than any cartoonist I’ve ever seen. For example, Naylor illustrates her and her friends inside jokes in one of my favorite comics of hers:

I had never seen an inside joke so well described in such a short comic. About this, Naylor says, “Drawing comics about inside jokes is so difficult, especially when a joke is less about the words you say and more about the way you say them. I’m glad people could relate to the phrase ‘leaning into your swords,’ which has a long backstory fueled by drunken nights of tarot readings. I want to get better at relating that kind of common language of friendship in comics, because there are plenty of TV shows that manage this (Broad City comes to mind, along with Insecure and recently I May Destroy You). I think inside jokes can be key in writing stories because they instantly illustrate two people’s closeness and shared history. Also: inside jokes can be some of the most hilarious things in your daily life, so there’s a certain validation that comes when you find they can make sense in a broader context. That doesn’t happen often– they’re usually exclusive to one friendship or relationship and can’t live outside of that. Which, to be fair, is also part of their magic.”

Naylor has many comics that are lighthearted, but she has the versatility to create incredibly profound, powerful work as well. It is truly breathtaking, given how short her work is. She also has an incredibly close-knit crew.

While the #relatable Instagram comics made by women only show themselves with their partner and family in their autobio, many female cartoonists whose work I love are guilty of it too. I may be reading too much into it, but it seems like an incredibly limiting life to not have friends close enough to include in your dailies. However, as I look through my own work, I see my boyfriend dominating my work, especially at the beginning of our relationship. While my friends are always present, my hard-core infatuation with my boyfriend at the beginning of our relationship dominated my thoughts, and thus my work. I make comics featuring my friends very often, but I’ve created an entire 42-page full-color zine about our relationship, something I have not done for anyone else in my life. I asked Naylor about it. We both are in the Washington DC area where it is incredibly hard to date as a woman, and many of her pack of female pals are also single. Naylor responded, “In terms of friendships <vs being in a romantic relationship,> it’s true that I oscillate with contentment and loneliness, but I sometimes struggle to discern if I’m really unsatisfied or if I just grew up in a culture that heavily emphasized the imperative of romance. It’s also complicated knowing that sometimes friendships develop through the solidarity of singleness. With single friends you can share in the frustrations of disappointing dates, unrequited crushes, and unfulfilling flings. I have a group of friends who proudly refer to themselves as ‘The Thornbacks,’ and we are very close.

However, I loathe the suggestion that friendships are just a balm against the loneliness of singledom. I think that’s often a trope in stories, and it really underestimates the deep intimacy that close friendships foster. In a culture that does emphasize romantic relationships, the varieties and shades of friendships are flattened unfairly. A friendship can have just as much of an impact, if not even more of an impact, as a romance. Close friendships are undoubtedly a form of love.”

This is the core reason I’m writing this essay and highlighting these works. I hate how trivialized friendships between women are in our society. I hate how my friendships are seen as lesser than my relationship with my boyfriend in society’s eyes. And it’s so insidious, I’m susceptible to this feeling too, it’s so ingrained in me. Naylor struggles with it as well, but the love she shows between herself and her friends just obliterates this bullshit societal narrative.

When I asked about the above comic, Naylor said, “In that comic, I go to a party where I don’t know anyone except my one friend Rachel, and there’s this implicit understanding that we can stand to do the vulnerable thing of meeting new people in an unfamiliar setting because we are doing it together. There’s a base level of comfort and care in that relationship that comes out naturally in a quiet moment on a porch swing with the recognition that a friendship can be a soul connection. Drawing that piece I worried that the comic could veer too much into sentimentality, but it was a genuine moment that I wanted to remember.

I think in the end, feelings and friendships are never one thing or the other. It’s not either ‘you’re single and empowered’ or ‘you’re single and sad.’ It’s ‘you’re single and empowered and sad and happy and fulfilled and you constantly crave something more.’ I want more narratives that embrace ‘ands’ rather than ‘ors.’ Life is complicated, and friendships are essential for navigating that complexity. Besides support, good friendships can bring a lot of joy to that journey.”

The fact that these authors tell stories of positive female friendships so differently and so well shows how complex and important female friendships are. The fact that so few cartoonists are making work on this topic shows how undeservedly undervalued female friendships are in our society. Even among the feminist authors I follow, of all genders, these types of stories are barely being told. I don’t think this is a dismissal of the importance of these types of relationships outright; I think that it’s not even occurring to cartoonists to write about friendships as a focal point in a positive life. But as Naylor says, women having friendships with other women is so crucial to a healthy support network and makes for a much richer life. I hope that more work is created celebrating friendships among women. I know that for the amount of joy my female friends bring into my life, they certainly deserve to.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply