Comics have always been a huge part of my life. I grew up reading comics and eventually became a cartoonist myself.

Some context: I was born in 1994 – which makes me a late millennial. I was an awkward preteen in the middle of the ’00s. I take pride remembering vividly the low-cut jeans craze, Britney Spears’ Toxic, wanting a flip phone, and the Disney Channel’s first live-action TV shows (and how terrible they were, don’t hate me). But that was also the era where I got deeply engaged with comics. Just like today, comics were more than stories with pictures: as a shy kid, they opened the doors to an alternate reality with characters that mirrored different aspects of myself and my aspirations, but they also made visible, but acceptable, all of my insecurities, fears, and shameful thoughts. In an age where you’re so constrained by self-doubt, it seems vital to most teens to have something unto which they can connect and hold on.

It’s 2020 and I’m turning 26. A friend recommended Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me (2019), written by Mariko Tamaki and beautifully illustrated by Rosemary Valero-O’Connell without knowing that, about 6 or 7 years earlier, I had been a massive fan of the Tamaki cousins. So, how could I say no? I read the whole graphic novel in one sitting, yet there was something that made me feel uneasy, or at least, slightly weird about it. For the first time, reading a young adult graphic novel, I felt old, outdated. As a huge fan of Skim (2005) and This One Summer (2014), both created by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t relate to this new approach in the same way that I felt so connected with the other two. The themes and the genre of Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me are practically the same as the earlier books, and the story had a lot of well-crafted parallels.

This essay is a (rather personal) effort to analyze the evolution of the YA genre on Western media and culture, through Literature, Film, TV and, of course, Comics, and how it impacts its characters and stories. How do the social and cultural changes in our society affect youth, growing up, and how it is portrayed? Have these stories — and their characters — matured, become more infantilized, or have I?

Young Adult and Coming-of-Age

Before addressing these two specific graphic novels, we first need to define the meaning of Young Adult and Coming-Of-Age.

Young Adult is a literary genre that emerged in the late 19th century and originally targeted audiences between the ages of 12 and 18. Meanwhile, the expression Coming-of-Age refers to a specific set of themes, tropes, or types of events that often appear in Young Adult narratives, but are neither synonymous nor limited to them. As the Oxford Dictionary defines it, the term Coming-Of-Age “may be devoted entirely to the crises of late adolescence involving courtship, sexual initiation, separation from parents, and choice of vocation or spouse.” [1] These themes are commonly associated with young adults and teenagers because they are the typical ages where we start seeking/demanding freedom and independence, but, as we know, these crises can happen at any time in one’s life.

We can briefly say that Young Adult refers to a target audience, while Coming-Of-Age addresses the specific topics and concerns explored in narratives, independently of its demographic target. Some remarkable Coming-Of-Age books, films, and TV series aren’t necessarily about teens, but instead, portray twenty-somethings or even thirty-somethings as main characters. In Frances Ha (2012, Noah Baumbach), for example, Frances, the protagonist, is a 27-year-old young spirit who can’t seem to find a way to figure out her life. HBO’s Girls (2012-2017) or Comedy Central’s Broad City (2012-2019) are two more examples of TV series who focus on young, but adult, women who are still dealing with typical adolescent dilemmas that are often at odds with what society expects from women of that age. The goal of these immature characters is to learn how to “act” like a proper adult. Hannah, in Girls, struggles to accept accountability for her actions and become a responsible, competent, and emotionally balanced adult.

Skim (2005) and Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me (2019), both written by Mariko Tamaki, are considered YA Coming-Of-Age stories because their focus is the transformational journey of their main characters into “adulthood”.

Since this is a medium that has been generally targeted for younger audiences, Young Adult and Coming-of-Age comics and graphic novels have existed for decades, even if we don’t immediately attach those labels. Take superhero Marvel Universe characters like Spider-Man or the mutants in the X-Men series: we’re often reading about teenagers that suddenly have responsibility thrust upon them and must overcome their own weaknesses and insecurities despite having superpowers. The success of the first teenage protagonist in Marvel’s history, Peter Parker, a.k.a Spider-Man, is often attributed to his connection to the increasingly culturally (and economically) relevant teenage audience of the early 60’s – but that doesn’t necessarily mean that Peter can be considered “relatable”. His problems might be relatable, but, as it often happens with superhero stories, their solutions are often aspirational wish fulfillment. Even though I’m aware that this statement is fairly debatable, early Spider-Man was still meant to be a fantasy.

Being Relatable

At some point, Skim wonders, while reading Shakespeare’s: “When you read Romeo and Juliet it doesn’t talk a lot about how Juliet was feeling when she knew she was in love with Romeo and wasn’t supposed to be. (…) I wonder if Shakespeare wrote a draft that had Juliet being so nervous, she had really bad cramps and had to pee all the time.” [2]

In 2015, Jillian Tamaki’s Super Mutant Magic Academy, an anthology of a former webcomic with the same name, was published by Drawn & Quarterly. Despite its slightly satirical title, it was not marketed as a superhero comic. This anthology collects a large series of comic strips and short stories that evolve a group of magical mutant students (reminiscent of Hogwarts or the Xavier Institute), but instead of focusing on their supernatural abilities, Tamaki chose to depict genuine, self-conscious, and flawed teens who happen to shoot lasers from their eyes. Instead of inserting teenagers into a fantastic magical reality, Tamaki brings this reality to them without their consent (or interest). As J. Tamaki said to The Comics Journal: “(…) I just think there’s a humor in the tension between being a superhero and being a self-absorbed teenager. (…) They don’t want these powers; they’re not a blessing for them. It’s funny because [the strip is] so Degrassi, it’s not at all Harry Potter or the X-Men.” [3]

This shows us that there’s a slight difference between writing a story about or focused on teenagers and writing an action story that happens to contain characters that are teenagers. The Tamaki cousins, Jillian and Mariko, were mainly interested in the first approach – exploring the complex and layered perception of being a teen and how it affects their views on the world, the society, and, of course, their emotions, relationships and its shenanigans. Both Skim (the eponymous protagonist of Skim) and Freddy (the protagonist of Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me) share the same idea of having unwanted feelings and emotions towards the recurring events imposed on them by their lives.

But, surprisingly, Super Mutant Magic Academy is a much cleverer satire of the genre; it’s an attempt to answer the question we’ve been always secretly asking while watching the X-Men fight a deadly menace in stylish pleather suits – What if Rogue were on her period? And how come they never have zits?

The mainstream superhero comics industry, headed by Marvel and DC, has long recognized the potential of the YA market. Both publishers have been rebranding and designing new characters to invest in a new approach to the genre.

Creating relatable characters and narratives can be as vague and broad as it sounds because all it takes is to have people relating to them or not. As Savage Books points out on his video essay on Netflix’s Bojack Horseman[1], people seem to be able to resonate with any type of character, from the Joker to GOT’s Samuel Tarly – or even Bojack himself, who was not primarily created or designed with that goal in mind but has been embraced by the audience for his “human” flaws. In the end, every character and story is possible to relate to, but some are written intentionally with that outcome in mind, using tried and true techniques for that effect.

Some of those techniques evolve creating characters that we can relate to physically, psychologically, or by experience comparison. For example, as a shy, chubby young girl, I was easily drawn to TV shows and books that included characters with these traits. Even though it was likely the only thing we had in common, I was able to see myself in the show and felt more compelled to engage with it.

Still, not only Marvel or DC, but big entertainment industries like Disney, are quite aware of the impact of creating relatable characters and, therefore, more inclusive narratives that connect with larger and more diverse audiences. Yet, diversity should not be a marketing strategy alone (at least we hope so). It’s a political and active choice of integrity and character that acknowledges that the content is made to resonate with and represent reality (and its audience). The power we attribute to representation also acknowledges the transformative, pedagogical power we put into stories – not only to reflect, but also to promote and perpetuate values, ideals of common and individual interest. Rebranded characters like the new Bat Girl or Kamala Khan, aka Ms. Marvel, represent a new take on teen superheroes that still fight crime and have amazing superpowers but also suffer from the mundane issues that their readers deal with. In the early ’00s, Disney Channel tried a similar take with Kim Possible (2002-2007), an animated series that follows 14-year-old Kim, as a rather relatable cheerleader that fought crime in her free time. The series emphasized the struggle of balancing a double life – during the week, Kim had to deal with school and family problems, and, in her spare time, she needed to gain strength, determination, and self-confidence to dismantle criminal schemes.

But in the ‘10s, this approach seemed to be going in a slightly different direction. It seems that having a double life is not as realistic as we wished or expected. Some new modern approaches prefer to blur the lines that used to separate the real girl from the super version of herself that arises after a transformation (just like Usagi, on Sailor Moon).

These new teen heroes were not going to transform or evolve from a shy, reserved self to a rebranded, better version of themselves – they didn’t have to because the whole goal was to embrace their identity, personality, and traits as there are. As Etela Lehozky wrote for NPR about Ms. Marvel #1, “Their [Adrian Alphona and G. Willow Wilson’s] Ms. Marvel, Kamala Khan, is an utterly believable teenager (…). Everything from Kamala’s postmodern mindset (she’s a superheroine who reads superhero fan fiction) to Alphona’s elegant line work make this a comic for the discerning reader. [5] This review not only praises the technical qualities of the comic’s writing and illustration, but also congratulates its approach to the character rebrand: “(…) Kamala [has] an expressive face and a normal girl’s physique. Kamala has no use for the typical heroine outfit either, finding that the original Ms. Marvel costume gives her «an epic wedgie»”.

It’s easy to see why the double life trope is so resonant with teenage audiences, as they themselves are between the worlds of childhood and adulthood and often seeking reinvention.

As we all know, YA has been getting exponentially popular in the last decades. Imogen Russell Williams wrote for the Guardian (in 2014) that this genre usually targeted teens between 12-14 years old, but has now a larger audience constituted mainly by adults. This doesn’t mean that YA is necessarily a juvenile, light-themed genre, though. Williams also points out that even Harry Potter, the acclaimed series of novels that brought attention and recognition to this new genre in the late ’90s, addresses mature themes such as murder or torture. But, still, “YA (…) is more likely to deal frankly with sex, tackle challenging issues and adult relationships, and feature swearing.” [6]

YA has gradually evolved into a genre that is not targeting a specific age gap, but a genre that approaches and explores themes and concerns that are usually connected to adolescence but end up relating to different age groups and generations.

Still, I believe it’s wrong to say that Kim Possible, or Usagi Tsukino (aka Sailor Moon), or even Hannah Montana, since we’re talking about teen girls with double lives here, aren’t believable characters. Like Kamala Khan, these characters also represented a specific mindset that corresponds to the contemporary values at the time they were created – which less and less correspond to the priorities we want to establish today. Probably, both Kim Possible and Hannah Montana were designed to mirror what girls aged 12 to 16 would want to be, while Kamala represents what many girls aged 12 to 16 are and can be.

The False Promise of Popularity

As we’ve seen, being relatable or not seems to be one of the most important characteristics to determine how well accepted a YA narrative is or not. But, relying on it alone can be simultaneously misleading. Skim (2005), This One Summer (2014), and, later, Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me (2019) are good examples of YA genre graphic novels because of their genuine, technical, and almost anthropological interest in adolescence as the theme, and not only because of a cathartic desire to create relatable content that people can simply identify with. Their stories are, indeed, relatable, but also because they’re full of real-life references that are familiar and close to most of their readers. Not just the characters, but the whole atmosphere in This One Summer, for example, feels printed out of an old photograph from our childhood summer day. It uses a rather standard aesthetic replicated on a collective memory to produce fiction.

Mariko Tamaki didn’t always feel like young adult fiction was about the experience of being a teenager, so it couldn’t truly mirror the haunting experience of being an anxious teen. As she says to the Miami New Times, “I don’t think Gossip Girl happens to any teenager I know (…) I think the idea is to stay within a visible realm of experience.” [7]

After her writing debut through indie graphic novels, Mariko Tamaki has been writing for DC and Marvel (She-Hulk (2017, 2018); Hunt for Wolverine (2018); X-23 Vol. 2: X-Assassin and Harley Quinn (2019)), and others, contributing to this new take on mainstream superheroes who claim to be closer to its new generation of young readers. As is often the case, YA and Teen Fiction will use schools, high-schools, summer camps, or other micro-societies as settings that can easily emulate, in a smaller and much more “harmless” scale, the real, larger (and scarier) environments that adults live in. [8] Until today, teen TV series represent, somehow, an eternal fight over the hierarchic roles established in high schools and middle schools that rely on stereotyped cast roles that should, somehow, resemble the experience that the reader had back in their day. These stereotypes are as close to authenticity as a caricature. If mainstream fiction wants us to relate to the main characters, it expects the opposite from other characters – the villains, the antagonists, or, in this general case scenario, the popular kids.

(Left) Disney’s Recess (1997-2001): The Ashleys were a caricature of the Mean Girl trope, popularized the late 90’s. They’re a clique of fashionable, snobby and arrogant girls who act cruel towards other kids that are not like them. Acting as a private club with limited member access, they contribute to maintain the social system that they benefit from. Source: Recess Wiki Fandom. (right) Shot from Heathers (1989), a dark comedy that explores the cruel side of highschool cliques and their social power.

But what does it mean to be popular, exactly, and why does it matter so much?

We can briefly describe the mainstream traditional “popular” archetype as the individual that seems to have it all. They’re an overlooked, powerful person that is praised for their good looks, who’s usually extroverted, demanding, assertive, and, above all, feared. Just like AMC’s Mad Men’s Don Draper, they’re also envied. They’re an unattainable ideal not despite but because, in most cases, they’re also a front.

In Freaks and Geeks (2001), a single-season TV series that portrays a group of teenagers in the late 80s, popularity and social hierarchy in the school environment is so determinant and central that it’s represented in the show title. Just like Mean Girls (2004), the series deconstructs these ideas by exposing them, using its layered characters to explore and indirectly critique how harmful, misguided, and useless labels can be. Early Disney live-action productions, such as High School Musical (2006), Lizzie McGuire (2001-2004), or That’s So Raven (2003-2007), are generally about insecure protagonists who don’t consider themselves comfortable enough to be who they truly are, opposed to their “popular” antagonists. This shows us that the main characteristic of the popular trope is that they seem to be sure of themselves, unlike the protagonists, who we are driven to identify with.

In High School Musical (2006), a modern-day cheesy interpretation of Romeo and Juliet, Troy and Isabella are two students who fall in love with each other thanks to the only thing they share in common: their passion for music. The conflict in this romantic-comedy-musical-teen-drama (wow) is that both protagonists are being forced by their social groups to stick to their social role, preventing them from breaking the stereotype by joining a shared interest – a school musical.

Until the late ’00s, the fictional hierarchy seemed to be an unavoidable cliché, but what seems to happen in Laura Dean Breaks Up With Me, and some recent YA graphic novels I’ve come across with, is that the strict social pyramid that I was so used to is slowly being subverted.

In the past few years, I am glad to notice that the tendency of today’s youth graphic novels and comics has been to draw attention to issues of a social character — from issues of gender, sexuality, social equity, and other topics that have been treated as taboos for the past few decades.

It seems to me that these novel YA narratives are more than just about pleasing a target audience; they are intended to be reflective of their target audience, but also to raise a new generation that does not seek to be labeled and stereotyped. The very notion of moralism becomes obsolete in these works since it is not about determining who is either good or bad anymore – these new narratives seek to dissect and deepen their characters in order to expose different angles and perspectives on the events.

Mean Girls, Popular Kids, Jocks, and Nerds – all these badges no longer stand for closed and profiled categories. The main character could be an insecure cheerleader that likes 80’s horror movies. The antagonist may be the punk honor student. Not every guy has to be a crude jock without any ambition or individual agency.

Graphic novels like Kiss Number 8 (2019, Colleen A.F Venable and Ellen Creenshaw) The Prince and The Dressmaker (2018, Jen Wang), Go With the Flow (Lily Williams and Karen Schneeman) or the Breakaways (Cathy G Johnson) are some examples of First Second’s catalog directed at a YA audience where the main focus is on empathy, awareness, and understanding.

Authors like Ngozi Ukazu, Cathy G. Johnson, Tillie Walden, Noelle Stevenson, Rebecca Sugar, and many others, represent a new generation not only in comics, but in the media in general, with greater openness and a concern for inclusivity.

So, what’s up with Laura Dean?

Both Skim and Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me deal with female queer protagonists who struggle with their own emotions towards their unattainable love interests. In the first one, Skim falls secretly in love with her teacher, Ms. Archer, while in the second, Freddy finds herself in a toxic relationship cycle with a girl, Laura Dean, who promises her more than she gives in return.

The stories are told from the protagonist’s perspectives, and we can access their points-of-view through two different levels: what we see, their actions and interactions with other characters, and their inner thoughts and feelings, revealed in a private journal (Skim) or personal letters (Laura Dean …).

In both stories, their potential romances are doomed to fail. Their love interests are intentionally hard to get, and the story is more about the pursuit to achieve their approval than their relationship (or lack thereof). Both Skim and Freddy end up feeling stuck and uncertain about themselves. At first, the protagonists are led to think that the reason why the relationship with their love interests is not working is mostly exterior: their social positions are incompatible (Skim can’t be with a teacher, insecure Freddy can’t keep up with the popular Laura Dean), but later, it’s revealed that the real issue is something else.

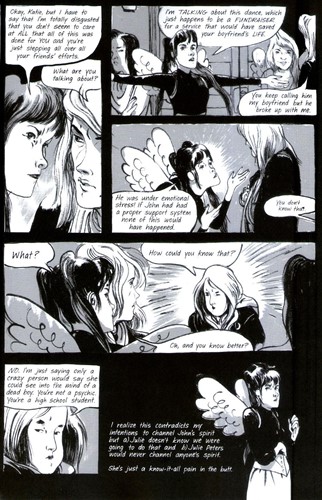

And this is where Skim and Laura Dean Keeps Breaking up With Me first clash: who and what represent these distinct love interests that, despite their obvious differences, cause the same harmful impact on our protagonists? What can we learn about both graphic novels and their take on YA just by analyzing the portrait and role of the main love interest? First and foremost, the infatuation Skim feels for Ms. Archer is secret and must be kept as such. Part of the anxiety Skim feels results from the struggle between wanting to love someone and simultaneously making that strong and expressive feeling go unnoticed: “How is it possible that

no one else can hear how loud my heart is beating?”[9] This book also addresses this issue from another angle: the suicide of a boy from a nearby school, John Reddear: “No one talked about John being gay at the ceremony. (…) Although Julie Peters piratically ripped Anna Canard’s tongue out when she brought it up afterward.“[10]

The dilemma between John Reddear and Katie Matthews is a narrative that runs parallel to the mainline of the story and unfolds the same kind of challenges that Skim overcomes without being directly aware of it.

Meanwhile, in Laura Dean…, Freddy’s relationship with Laura is not a secret – on the contrary, Freddy wants it to be public and acknowledged in order to be considered official and, therefore, real. In Laura Dean…, the taboo problem is not the secrecy of the sexual orientation of the protagonist, but the classic problem of any love story: does she love me or not? Being queer or not is not the main theme discussed in the narrative in the sense that this theme is not treated as a peculiar exception, but rather as part of the reality of the 21st century.

Perhaps the question is really: how does a problem as classic as an unrequited passion apply to the social and diverse context of Western youth in the 21st century?

Freddy’s problem is beyond accepting her sexuality, but how to reconcile it with the rejection of her love interest – a problem that for a long time was usually represented mostly by hetero and cis couples.

At some point, Freddy even acknowledges, ironically, the situation: “Of course, I know there are LGBTQIA activists out there who fought for centuries for me to have the right to fuck up like this. I’m aware that I should be grateful that I have the ability to get broken up with and publicly humiliated the same as my hetero friends. I am progress”.[11] This monologue happens at the same time Freddy’s class is discussing Harvey Milk, where some of her classmates still have lingering, inappropriate opinions. The graphic novel points out that the coming out doesn’t necessarily mean that the past is buried. “Embarrassing progress”.

Laura Dean, meanwhile, remains silent towards this discussion – as it doesn’t really affect her. Take’s video essay[12] points out that the “Mean Girl” is a trope usually defined by a confident, ambitious, and, obviously, good looking popular female character. But, unlike the Jock, the most obvious male equivalent who’s usually rendered as a shallow and dumb character, the Mean Girl earned her crown not only because of her elevated status or her looks but due to her perceptive, manipulative, and therefore toxic demeanor. The Mean Girl takes her qualities – being assertive, charismatic, and self-assured – to a negative, toxic extreme, using them for her own, selfish benefit.

Laura Dean falls into a new interpretation of this archetype. Laura shares some of the same standard characteristics of a classical 00’s Mean Girl – she’s manipulative, charismatic, and envied. She has an extroverted and out-going personality and has no difficulty in demanding from everyone what she takes for granted. She is popular in the sense that she has several people with whom she can choose to spend time with, letting Freddy feel like the last choice. Laura can become truly intimidating as well, Freddy can’t take her for granted because she’s not the one in control. And even recognizing her flaws and toxicity, Freddy can’t help but be carried away by her charms. In the end, Freddy just wants to feel recognized, appreciated, and loved by someone that we all know, even Freddy, won’t be able to do that. And Laura can be all of that and more without falling in the cliché of the mean, sexy, cheerleader prom queen.

MTV’s TV Series Awkward (2011-2016) depicts a vaguely similar situation. Jena, the protagonist, is struggling to feel accepted by her love interest, the good-looking and (obviously) popular jock Matty. This story is also told from Jena’s perspective that, just like Freddy (and Skim), writes down all her thoughts in a journal. Both Jena and Freddy end up feeling guilty and unworthy at several points about their relationship with the over-romanticized love interest. But the main difference between these two is that Jenna projects all her hopes and dreams not exactly onto Matty, but onto the idea of engaging with someone like him: “Guys like Matty don’t go for girls like us.” On the other hand, Freddy doesn’t mention as much their romantic interests’ status – they seem to be focused on seeking real “love”, establishing a true connection that will make them feel cherished and special. Laura’s popularity is mostly considered an obstacle or even a flaw, not an envied prize.

But these girls feel lonely most of the time, despite having the support of friends and peers. Their struggle is fundamentally intimate and internal, and they seem to take it as an individual problem from the very start. Both Jena and Freddy have warmly supportive friends, but from whom they do not rely on for advice, even if they ask for it (a lot). This makes the protagonists, at a certain point, shut themselves off in their problems in such a way that they don’t even realize that their friends have their own challenges too and that they may need support as well.

Both Jena and Freddy can’t rely on their young-type, bubbly parents either, forcing them to become self-resilient. Adults are rarely seen to be reliable in these narratives at all. While in Skim the parents take a nearly absent role, Freddy’s parents behave as much as an extension of the group of friends as they simultaneously reflect the ideal of a loving relationship that Freddy cannot achieve. They don’t give the psychological support or the security that, in turn, is put in friends and peers that show the traces of maturity that the protagonists can’t find in their parents.

In most of the stories I grew up with, just like Skim, teenagers’ personal lives are religiously kept out of the relationship with their parents – they are completely incompatible. However, in Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me (2019) and even in Awkward (2011-2016), the parents detach themselves from the classic authoritarian and opaque fatherly figures and acquire some of the characteristics that we would have attributed, until now, to other characters in the circle of peers of the protagonists – they’re also flawed, they have insecurities but, mostly, they’re not always right.

Freddy’s parents are not only oblivious of their daughter’s distress, they also encourage and participate in the myth created around Laura Dean, as if they were proud that their daughter is hanging out with someone like that: “Hey, Laura’s back! Laura’s cool. Laura DEAN. Like a movie star or something.” I’m not saying that they’re terrible parents – they simply hold the general belief that being in love is the best and only necessary thing there is, above everything else (even your mental health state).

Finally, MTV’s Awkward stands right in between Skim and Laura Dean… when it comes to its relationship with the internet. In Awkward, we already have the impact of the internet on communication (Jenna writes a blog, there are quite a few references to MySpace, but mostly texting), but we hadn’t yet reached the ubiquity of (and addiction to) social media that we currently live in. Still, Jenna’s blog already opens a window to explore the damage of exposing your privacy online.

Skim also addresses the archetype of the popular girl and her clique, but without providing the same power or protagonism as we have seen so far in previous examples.

Skim tries to deconstruct Katie and her group of friends by showing how, behind the rumors, they too have insecurities and weaknesses, but most of all they suffer and can be hurt as well. The cliques and social divisions are consequences of a lack of empathy or communication. The thing that will unite Skim with Katie, in the end, is the shared ground that none of these girls were able to establish with the groups they thought they belonged in the beginning. Here, “mean girls” are not necessarily cold-blooded villains, and their attitudes are not purposefully evil or destructive. The damage they cause is essentially collateral, a consequence of their narcissistic and self-centered naïve character, which does not always allow them to consider the well-being of others.

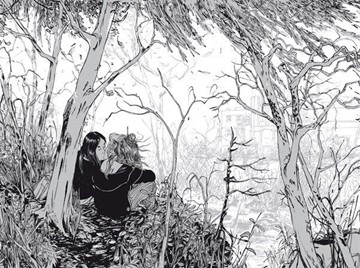

In Laura Dean…, the love interest and the mean girl merge into the same persona – in other words, what the protagonist wants is the same thing that destroys and prevents her from progressing. Skim’s love interest, Ms. Archer, differs into another type. Ms. Archer remains an idealized figure, of whom we know little or nothing of as readers. Skim writes that they spent hours chatting, while the teacher held her cast arm, as the only proof that there was a certain level of intimacy.

I’ve always read this graphic novel divided into two parts: before and after the silent kiss between Ms. Archer and Skim. But, contrary to what one would expect, the kiss will not be the beginning of the romance, but the root of its rupture. Laura Dean starts long after the first (or tenth) kiss. But the problem remains: are these feelings I have reciprocated?

Laura Dean… is an XXI century teen romance story not only because of the obvious style references, but mostly because the narrative is deeply affected by the existence of social media. The anguish and suffering are aggravated because the distance is fundamentally emotional. As Freddy writes: “Like, she’ gone, but she’s not gone. (…) I can still text her.” The pain is caused by having to deal with the remoteness of a person who is still there as if it permanently reminds us that they don’t belong to us.

Social media amplifies this effect by allowing physical distance to become an abstract measure. We don’t need to stand next to someone to stay in touch with them. The access to public and private life merge in a single layer that can be unveiled through an endless scroll of an app. And while Skim suffers from Ms. Archer’s physical and emotional absence, Frankie finds it harder to give up on Laura because she continues to have her present in her life over and over again, even if it is not necessarily in person.

This particular feeling could not be more relevant, not only in terms of our relationships, but also throughout the current circumstances in which we are living. The Internet and social media have allowed us to be in innumerable simultaneous spaces and realms, even though we may only be in one, physically. We have become dependent on our newfound and expected omnipresence.

The anxiety Freddy feels about Laura Dean turns out to be different from what Skim feels towards Ms. Archer since, in the 1990s and in the context of Skim, being near or far from someone was essentially an emotional or geographical logic. Adding to this, Freddy must deal with Laura not only in her physical and emotional presence and absences, but also through the abstract digital reality of social media, where proximity can be more toxic than distance.

And yet, both stories end with fairly optimistic endings.

Freddy realizes that she has to break up with Laura Dean and get out of the toxic cycle in which she is immersed in order to be happy and move on. She learns to value herself in her own individuality. However, in Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me, the conclusion is more straightforward. Anna Riley, the columnist to whom Freddy writes and narrates her life throughout the book, finally answers and concludes all the things the reader has to withhold from this tale: “The truth is, breakups are usually messy, the way people are messy, the way life is often messy. It’s okay for a breakup to feel like a disaster. (…) It’s also true that you can break up with someone you still love. Because those two things are not distinct territories: love and not loving anymore“.

In Skim, although the message is broadly similar, the end is more diffuse, and M. Tamaki does not provide us with a prepared speech. The idea comes across in subtext: through Skim’s diary entries, her thoughts, opinions, and questions about the most varied things, the reader creates their own opinion and insight into the story. The descriptions of the events are subtle and preserved by a safe distance – just like Skim who never lets herself be too exposed and sets up a natural barrier that prevents her from being forthright with how she feels.

Unlike Freddy, all of Skim’s suffering is repressed under silence and secrecy. The transformation is essentially internal, a hard, difficult growth that leaves her wounds so deep that Skim feels the need to change her physical appearance by bleaching her hair.

The situation is not any less painful for that, but for those who perceive it from the outside, like their best friend Lisa, the changes in Skim are practically nonexistent. “Being in love changes you, you know?” Lisa asks. “It’s just… it makes things different, you know? It’s like, you turn a corner”. The final dialogue between Skim and Lisa proves how completely oblivious Lisa was to the situation that Skim overcame and simultaneously concludes, in a very brief way, the positive aspect of her romantic heartbreak. We don’t need to know, as readers, whatever happened to Ms. Archer, because the narrative has proven that she’s not the ultimate love interest, i.e., the moral goal of the protagonist. Ms. Archer is the accident that allowed Skim to grow up, complete the arc, and evolve.

How about now?

Writing and thinking about these two graphic novels, as well as the role of the YA genre, made me reflect not only on my own experience as a teenager but particularly on the responsibility and mission that one acquires when creating stories.

Unfairly, I assumed that I may not be able to relate to this new wave because I didn’t grow up with smartphones or Tik Tok, but now that just seems to be a sterile and superficial observation.

There has never been such an actual, wide-ranging, and diverse approach to adolescence and its problems as we have now. Today’s approach does not depend only on stereotypes or a close-knit group of references that hardly reflect the surrounding reality. It is a reaction to the ever-growing number of new voices within the medium that contribute with new visions, perspectives, and enriching narratives that do not rely on any age group to be interpreted and appreciated.

More than ever, I feel I can still learn, at 26, 36, or 86 years of age, especially in an era when the idea of being an adult and growing up has become both relative and abstract.

Comics and other media are and must be portals that reflect different experiences and perspectives, of which we should all want to be a part, learn, and contribute.

References & Footnotes

[1] https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095626688

[2] Skim, page 70

[3] http://www.tcj.com/supermutant-children-an-interview-with-jillian-tamaki/

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ku8GWvE-vhg&t=1153s

[5] https://www.npr.org/2014/10/16/354592028/shazam-rebooted-comic-heroine-is-a-marvel

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2014/jul/31/ya-books-reads-young-adult-teen-new-adult-books

[7] https://www.miaminewtimes.com/arts/mariko-tamaki-on-this-one-summer-young-adult-writing-and-queer-lit-6514439

[8] In the late ’00s, there was an expansion on post-apocalyptic / sci-fi / dystopian fiction in the YA genre and these rules may not apply in the same way.

[9] Skim, page 46

[10] Skim, page 95

[11] Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me, page 31

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3AgCDkiKlhE&t=701s

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply