The police are incompetent, the politicians are paranoid, the scientists are selfish. The newspapers are full of fake news, and the courts imprison the innocent. In the swirling Belle Époque storylines of Jacques Tardi’s The Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec, anyone looking for modern resonances about the state of things will find some familiar handholds. Tardi’s true focus in the Adèle stories, though, turns out to be neither Adèle’s time nor ours, but a calamity in-between. Set in 1911 Paris, the story’s subtexts circle World War I like a rock caught by a black hole, and if Adèle‘s characters are oblivious to their connections with the Great War until it’s too late, a reader of the stories can hardly miss the sense of escalating doom and futility looming over everything. Tardi depicts a population about to find the full weight of history pounding them into the mud. We should hope the story’s signposts point in a different direction for us.

WWI is Tardi’s consistent artistic project, the topic he has approached from multiple angles over the years without allowing his incandescent anger to curdle into obsession, even when the stories he tells have involved his own family. “The only thing that interests me is man and his suffering,” said the artist, echoing the thoughts of Francisco Goya. “And it fills me with rage.” He said this in the foreword to It Was the War of the Trenches, a long gestating war story eventually published after the Adèle series had set sail, which gazes directly into the pit of WWI; however, the same sentiment bubbles underneath Adèle Blanc-Sec’s adventures too. In Trenches, the disasters of war are colossal enough to throw cause and effect out of whack altogether. Terrible Goya-esque sights appear, drawn in Tardi’s atmospheric black and white line, with Letraset grey tones making the landscape seem polluted and sickly. The corpse of a horse hangs in a tree; a slumped soldier holds his helmet in front of his belly and reveals that his innards have spilled into it; acts of kindness lead only to death. For the bulk of the book, Tardi sticks to an unbreakable rhythm of three horizontal panels per page: the sombre drumbeat of an execution, or a parody of the French Tricolour.

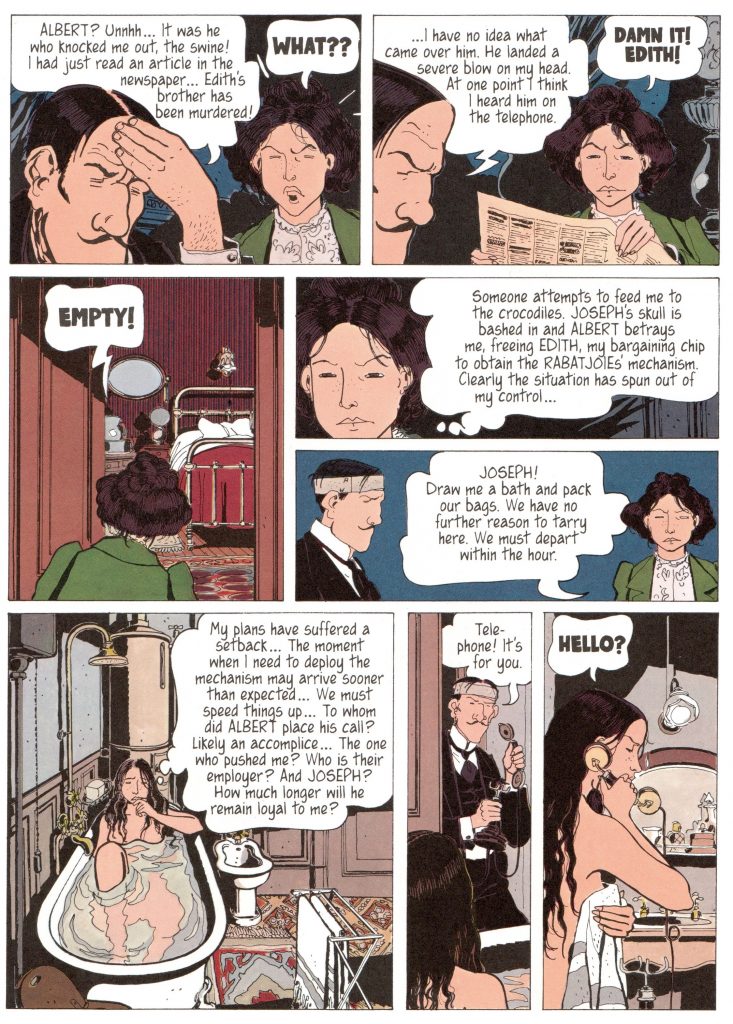

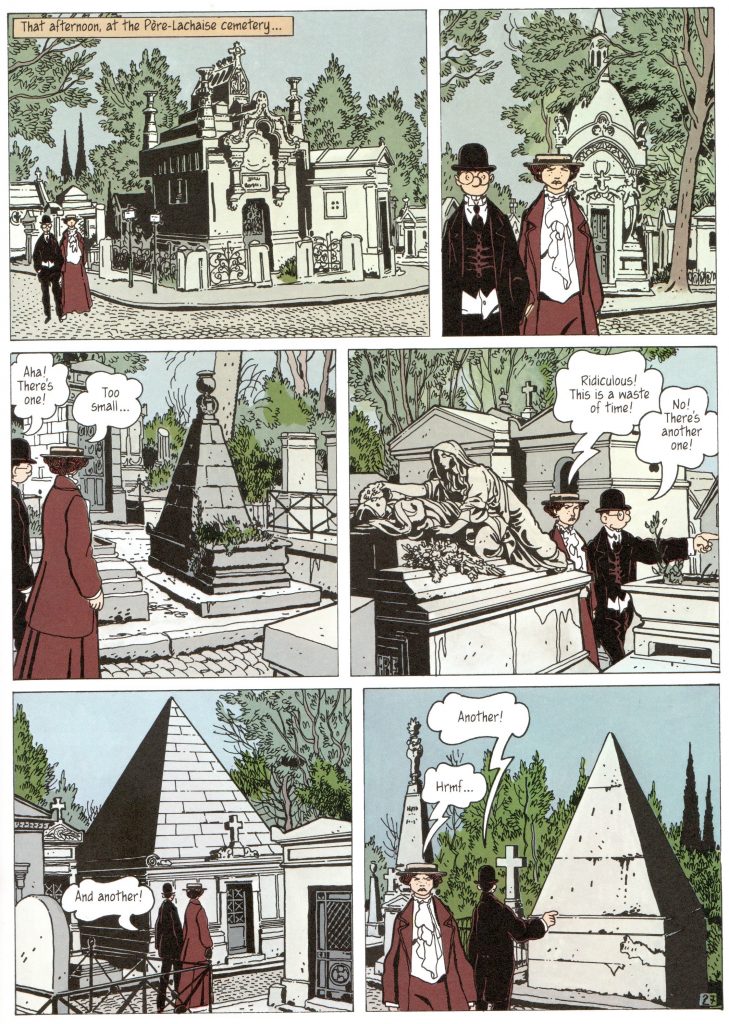

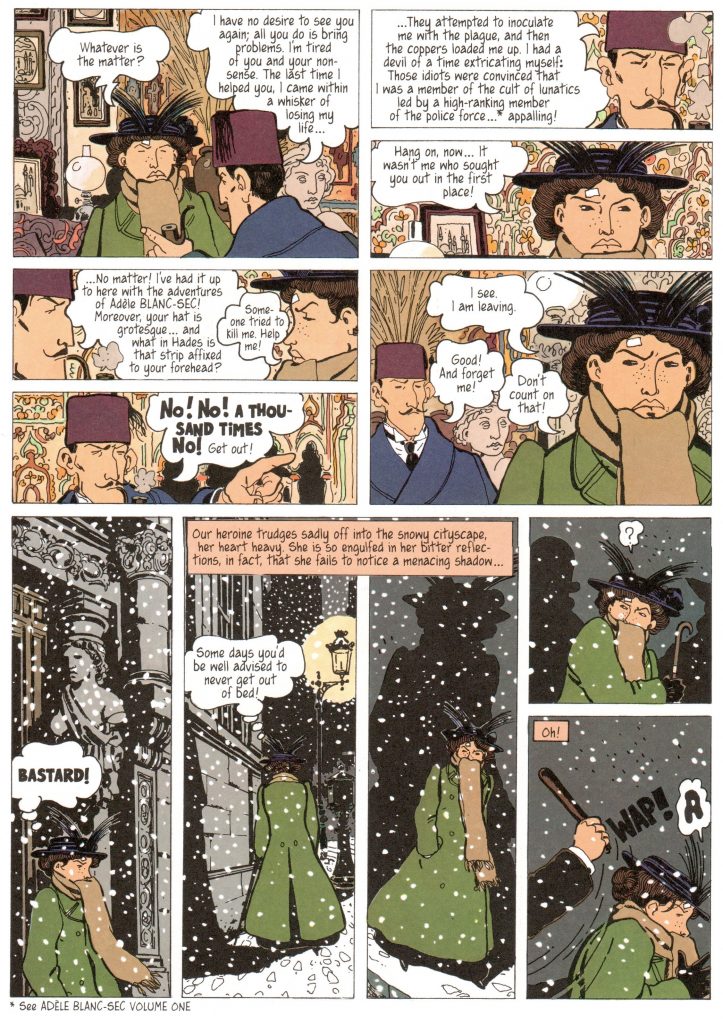

Adèle takes a different formal tack into what seems to be less bleak territory. Its freewheeling spirit conjures up the style of a 19th Century feuilleton, with some mild romance layered over downright fantastical events in plots that charge recklessly forward. Tardi adds some steampunk sci-fi to the pot too, with multiple mad scientists and implausible gadgetry leaving the Parisian elite dumbfounded at the machines their era has created — and unaware of the uses those machines may soon be put to. The art is lush and colourful, all crowded panels and lengthy speech balloons, complex pages to match the complex narratives of the stories and a long way from the static cruelties of Trenches.

The turbulent pre-war times call forth a turbulent woman. In The Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec, Tardi deliberately starts Adèle’s first adventure with a narrative knot that takes some untangling, introducing his heroine while she is in the process of impersonating somebody else and declining to clarify matters for the initial 20 pages. When he does, Adèle’s heroism is balanced by waspish intolerance and a dash of misandry. Apparently a novelist who constantly stumbles across mysteries — so Jessica Fletcher avant la lettre — Tardi’s grouchy heroine’s impatience with most of the (male) characters she has to deal with ends up feeling like another facet of her creator’s unhappiness at the state of the world.

Fantagraphics was in the process of reprinting the Adèle series under the guidance of Kim Thompson before his death in 2013, and they published the first four stories in two volumes. Each individual story showcases Tardi’s charismatic cartooning and madcap adventuring, while foregrounding a resourceful female daredevil of exactly the kind you might expect to catch the eye of film director Luc Besson, who bootstrapped elements of them into a feature film in 2010. But read en bloc, covering two years in the life of Adèle from 1911 to 1913, the creeping shadow of some dire approaching collapse gathers over the stories before gathering over their protagonist too.

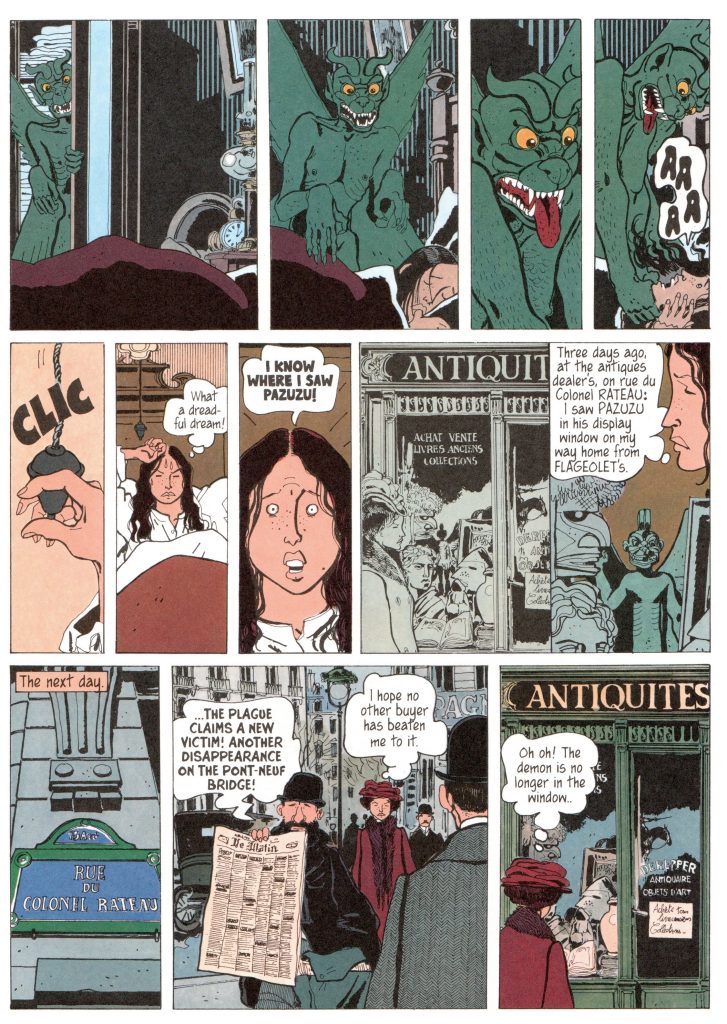

The first tale is relatively benign: “Pterror Over Paris” involves a pterodactyl hatching from an egg in the Paris Museum of Natural History and promptly sending all levels of French society into crisis, while Adèle herself is occupied in a noble piece of espionage to help an innocent man escape from prison. The second story, “The Eiffel Tower Demon,” is a measurably darker story, with Adèle stumbling onto a conspiracy of demon worshippers aiming to release a plague onto the citizens of Paris. Its jokes are more deadpan — Adèle sits scowling throughout the performance of a cheesy stage play while everyone else watches in rapture, the last arts patron of taste in the City of Light — and the conspiracy is deadly serious, revealed to be a confederation of the city’s supposedly great and good, led by the corrupt Police Commissioner himself.

Story three in The Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec is “The Mad Scientist,” in which the great advances of French science become simply cruel. A 300-million-year-old ape man is reanimated and, despite Adèle’s misgivings (“Have you never read Mary Shelley?“), proves to be more cultured and sophisticated than the boffins who brought him back. The callous scientists brainwash the Pithecanthropus to become a living weapon, and dream of marching on Moscow to avenge Napoléon.

It is in the fourth story, though, where everything implicit becomes explicit. “Mummies on Parade” finds Adèle in 1912, with more devil worshippers at work in the crypts of Paris and another resurrection, this time of the ancient Egyptian mummy Adèle keeps in her apartment. The mummy also turns out to be an intellectual, but this representative of the unquiet dead sniffs the air and leaves France almost immediately, aware that something dreadful is coming. “Your country will suffer horribly,” he tartly comments. “Farewell.” After he departs, this fourth tale ends with a burst of what Tardi himself called “extreme confusion,” as characters from an entirely separate Tardi serial, The Arctic Marauder, charge onstage unannounced. In the ensuing melee, Adèle Blanc-Sec is stabbed to death on-panel in her own story. While Tardi eventually brought her back, he made clear at the time that she was finished and packed her off into suspended animation. The story’s calendar had reached August 1914, and Tardi himself had reached It Was the War of the Trenches. Rather than force his endearingly caustic heroine to get stuck with a role as some clichéd wartime Mata Hari, he removed his queen from the board altogether.

“WWI really does explain and to some extent construct the world in which we live today,” Tardi told The Comics Journal in 2013, and the Adėle stories put an outwardly exuberant mask onto another of the artist’s attempts to find a rationale for this dreadful fact, to make sense of the inconceivable. Bittersweet and raucous, they show the Belle Époque oblivious to the madness seeping in through the cracks. As the clouds gathered and the ghosts became anxious, Tardi took steps to keep Adèle Blanc-Sec out of Europe’s slaughterhouse by sentencing his creation to a shockingly random death that presages a few million others. Only a cartoonist of the deepest compassion could have contemplated doing such a thing.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply