Office decorum was for squares, corporations, drones in their little cubicles. We rejected all that instinctively. We probably broke a hundred labor laws every week. I don’t think Kim and I saw ourselves, at that time, as business owners or “management” or bosses. All the people we hired were about our age. There was almost no distinction between employee and employer. We were on a mission and the only reason we even had a business is because we couldn’t accomplish what we were doing without one.

––Gary Groth

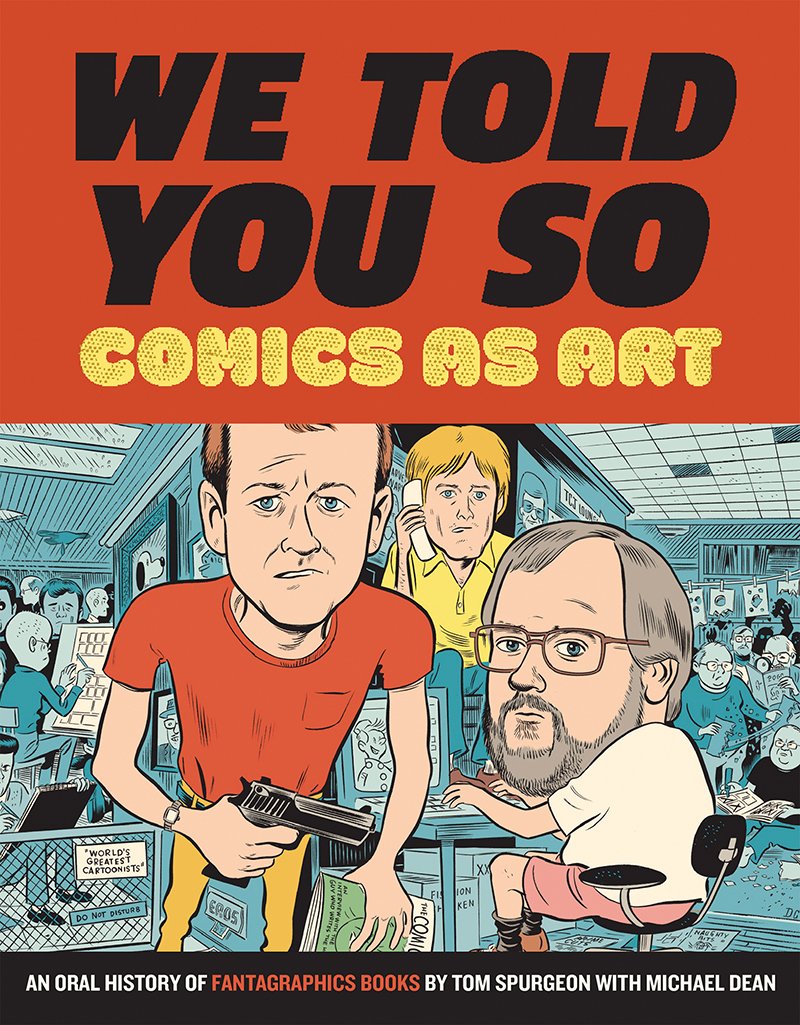

Reading Fantagraphics’ We Told You So: Comics as Art was probably a perverse thing to do in the first place. The six-hundred-page book, ostensibly an oral history of the publisher’s history, lets you know from the title that it’s as much a victory lap as it is a historical account, and its fondness for its subjects makes for a chummy, oddly forgiving (self) portrait. Editors Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean seem to have understood their purpose strictly within the confines of conducting interviews, gathering material, and thereby presenting the “warts-and-all” story of Fantagraphics; they don’t contest, critique, or even much contextualize the claims made by its interviewees.

Their editorial reticence is characteristic of alternative comics, which has always imagined itself in existential antagonism with moral-watchdog censorship and company-owned intellectual properties. As an upside, then, this book is assembled with the same logic that its subjects describe in interviews and comics. And although every hate-read feels a little like a masochistic self-own, We Told You So at least turns out to be a usefully concrete archive for a well-established version of comics history. By reading for rhetorical framing as well as historical fact, readers can take a closer, more critical look at how the story of comics’ rise has been fashioned.

We Told You So tells a specific story about comics criticism, indie comics, and Fantagraphics as a publisher, which can be boiled down at least halfway to R. Crumb’s backhanded love letter in the book’s preface. “In truth, Fantagraphics […] is barely a business at all,” Crumb writes. “There isn’t a real ‘businessman’ anywhere to be found in the organization.” The way this story goes, there are no businessmen in this side of comics: only artists who are animated by and repressed for their exuberant, rambunctious energy. That vitality is crucially not an act of labor per se (produced for capital or commercial interests), but an activity like eating or fucking or blowing up toilets at a work party: it’s all about being alive, pulsing with cum, and being cool in a way comics nerds weren’t supposed to be cool. At root, Fantagraphics’ purported distance from commercial publishing is both proof and possibility of their comics’ riotous vitality: a liveliness that relishes all of the “morbid distortion[s]” (disability, queerness, criminality, etc.) that the Comics Code Authority of 1954 named forbidden material.

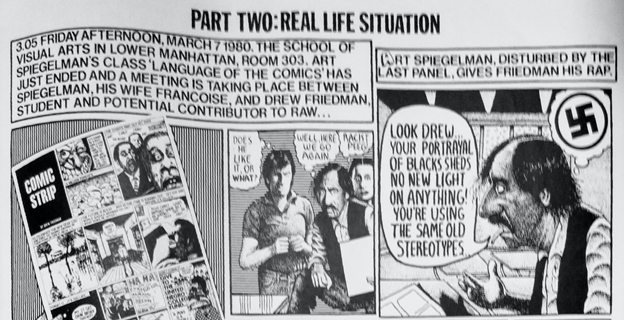

A short detour: around the same time Fantagraphics started publishing comics in the early 1980s, cartoonist Drew Friedman added Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s discomfited reactions into his antiblack comic for RAW magazine, making a joke both of their distaste and of the centrality of racist cartoons to indie comics (“How ‘bout Crumb?” Friedman’s avatar asks, to which Spiegelman exclaims, “Crumb admits he’s a racist!”). The two editors’ investment in making a place for Friedman’s work outweighed their apparent distaste, since Mouly’s request to remove “that offensive last panel” isn’t reflected in the final comic, and the meta-discussion ends with a second racist punchline.

I give this anecdote of another publisher’s editorial retreat as a hint that the appearance of racist caricature––whether in the pages of RAW or in a Fantagraphics publication––is more than a chance side effect of alternative comics’ anti-censorship principles. Indeed, just identifying the racist and misogynist parts of We Told You So would feel a little obvious; no disrespect to the late Tom Spurgeon, but this project was always going to be mostly-white guys talking to each other about how they rescued comics. For the moment, what I’m most interested in assessing is not whether or not such images should appear in alternative comics, but why they so frequently did: why, in particular, white cartoonists have found aesthetic edge there, and why editors and publishers have positioned those artists as central to the history of comics-as-art.

Here is another way of asking the same question: what is useful about racist caricature to alt comics and its self-image as a lively, unruly art?

As a self-portrait, We Told You So has two main rhetorical aims: first, to characterize Fantagraphics as an unruly artist in its own right (“iconoclastic, independent”––indie signifies multiple things here); and second, to demonstrate the company’s key role in pushing the medium via criticism and publishing (“so that cartoonists such as Daniel Clowes, Chris Ware, Joe Sacco, and many more could thrive”). Both of these aims entail a familiar romance with marginality and misbehavior, one not so far off from Scott Bukatman’s affectionate account of Winsor McCay-esque comics/cartoons as dreamy “fields of playful disobedience…little utopias of disorder, provisional sites of temporary resistance.”

The idea that comics as a tradition are inherently subversive in a cultural/political sense is old hat, but it often gains traction by specifying underground comix or alternative comics because of the underground movement’s roots in 1960s counterculture. (In one odd comment, Gary Groth even associates Crumb with “progressive cartoonists.”) The romantic view has its roots in a genuine crisis for comics publishing, post-1954, but comics criticism as a whole needs to start collectively and enthusiastically spitting on the idea; otherwise, we risk misunderstanding how power works at this odd intersection of a subculture and an industry––and risk allowing the publishers themselves to frame this history.

In This Comic, Kim Deitch Is An Asian Woman

Between interviews relating the various instances of Fantagraphics bro-mythology––turning a Connecticut mansion into a fratty workhub, publishing Love and Rockets, moving to SoCal and then Seattle, shooting guns together, and presenting Gary Groth with a “big black cock” chocolate cake––are an assemblage of photos and short comics. It’s the comics I want to pay attention to here, since each addresses Fantagraphics and comics publishing. Drawn by artists such as Kim Deitch, Ho Che Anderson, Roberta Gregory, and Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, these comics offer a partial view into artists’ relationships with Fantagraphics, as well as offering the self-portrait a satirical edge of self-deprecation. Most are autobiographical in some fashion, speaking through their own avatars or through their most famous characters. Some are full of pointed jokes, some are dreamy and fannish, and some are an interesting mix of the two: a faux-satire that turns backhanded compliments into kisses.

As a genre, satire often receives our suspicion by being too haughty, too glib, too hamfisted (or too cryptic), and for paranoid readers, any uncertainty in assessing its irony (“not sure this is satire” / “if it’s satire, it’s not obvious enough”) can act as a damning criticism in itself. Satire might have the most power in that bit of uncertainty––in the contrarian position of half-seriousness––but that same uncertainty also makes readers fairly unforgiving and demanding. You want to parse the joke and you want to know who’s at the punchline, and often you want to know who’s telling this joke anyway.

When it comes to comics, I get why readers don’t want to give works of satire the leverage of ambiguity; it’s the first line of protection for artists like Crumb, who still holds a canonical status in comics criticism. The pleasure these works take in ugliness animates a contempt that is often tricky, multidirectional, and mobile––sometimes even dishonest with itself.

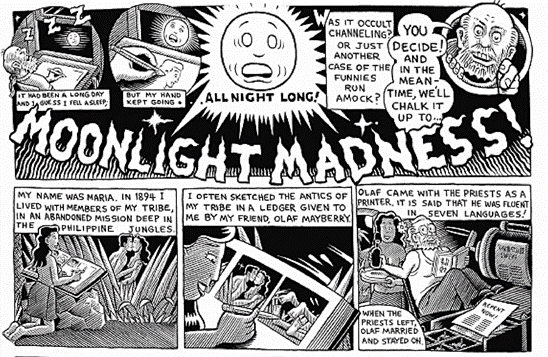

Not too many pages into We Told You So, just after the R. Crumb preface and a one-page comic from Tim Hensley, you get one such satirical work: Kim Deitch’s five-page comic, “Moonlight Madness.” Because of its location––before any of the interviews––and because it is a longer, allegorical piece, this comic introduces the book’s larger thematic blueprint. Deitch takes a mock-spiritualist approach to the origin story of Fantagraphics Books, spinning a fantastical allegory of censorship, pornography, and re-animation. Here is its plot: after falling asleep at his drawing table, Deitch accidentally channels the ghostly spirit of fictional erotic cartoonist Maria, a woman in 1894 from “an abandoned mission deep in the Philippine jungles.” Through Deitch’s sleeping hand, Maria’s tiny, naked spirit-body narrates a tale of eroticism and repression. After making pornographic comics based on “the antics of [her] tribe,” two men––her lover (the distributor) and her friend (the printer)––are inspired to help her reproduce and distribute them. Conservative townspeople respond to her comics with shock and disgust, however, and Maria’s lover is jailed for distributing them and dies in jail, followed closely by their printer and Maria herself: death-by-heartbreak.

Although Maria, her distributor-lover, and her printer all perish together at the hands of colonial censorship, the two men have already been reborn in the twentieth century as Gary Groth and Kim Thompson, two of Fantagraphics’ founders. Maria, too, is soon to be reborn as comics’ “newest and most innovative star,” but her main function is as narrator and relay. Through her sexuality and artistry, the innocent, only-accidentally-inflammatory erotic energy of brown sex (“the antics of my tribe”) gets transmitted into her friend and lover. Those men reemerge from death to create Fantagraphics, which in turn, distributes comics to the “ever more remote corners of the world.” Deitch communicates this futurity with a recourse to ironic/nostalgic racism: a futuristic Fantagraphics airship dropping crates of comic books onto racist caricatures of black Africans.

Deitch’s allegorical retelling of moral panics and the medium’s rise to legitimacy makes mixed use of colonial aesthetics. It’s an allegory that exports the story of comics repression to a different colonial context––an Asian “elsewhere” that also allows him to import anticolonial rebellion and sexual vitality to American alt comics. As satire, the comic’s half-seriousness is situated in its attachment to anticolonial sexuality, which is here both a target of mockery (“the funnies run amock,” reads one pun) and an object of intense identification. Comics production and distribution emerge in a “remote” colony under repressive circumstances, and are so inherently linked to such alterity, although they must be re-animated in white bodies to reach the golden age of artistic legitimacy and global distribution.

Although Deitch’s racist iconography is a familiar part of the underground comics tradition that preceded Fantagraphics and “alternative comics,” its use as part of the publisher’s own origin story clarifies more about the company’s mythos than any sincere self-portrait. Deitch channels a brown woman whose color vanishes upon her death; her wriggling, beatific spirit body is a bright white, visual contrast against increasingly busy scenes of Fantagraphics’ “bulging warehouses.” Her narrative presence acts as a confirmation and a blessing upon comics’ literary/artistic success––a success proven by Fantagraphics’ reach into a timelessly anti-modern Africa.

In Deitch’s vision of subversive comics publishing, the artist makes comics as an act/record of erotic vitality, and the amateur-publisher and -distributor circulate that pleasure out into the world. Importantly, their relation to the artist is more intimate than businesslike, even in the imagined future where Fantagraphics achieves its wildest distribution dreams. For Deitch that intimate relation may be real; the interviews in We Told You So confirm that the publisher expects to lose money on his books. (“If we can publish a Deitch comic or book and lose, not our shirt, but just a sleeve or so, I’m ok with that,” reports Kim Thompson, whose treasured childhood comic was Tintin in the Congo.) Thompson and Groth were big fans of Deitch from his underground comix days; for them, he’s “obviously one of the greats” and simply “such a sweetheart.” But intimacy in such exemplary cases also hides the power negotiations inherent to every publishing contract, as Mary Fleener’s comic hints between fond reminisces: “When it came to contracts, he [Groth] liked to spar a little.”

If “Moonlight Madness” weren’t so snide or so farcical, its allegory might read more obviously as romantic mythos, a way of buying into Gary Groth’s belief that Fantagraphics had “almost no distinction between employee and employer,” that it perhaps was the subversive “anything-goes atmosphere of libertine liberality” Groth imagined it was. But a workplace’s disdain for decorum and non-identification with business doesn’t automatically make for an equal playing field, as anyone who’s heard “we’re a family here” on the job can testify. (Indeed, Bill Gaines tried the same chummy ploy at EC to mixed reactions.)

As it is, the joke of “Moonlight Madness”’s frame narrative––channeling a brown woman artist from another time and place––acts as both source and alibi for a potentially embarrassing romance. Satire gives it ample cover, although what makes Deitch’s comic interesting is its literalness, which streamlines and so clarifies the anti-capitalist story alt-comics tells about itself.

Deitch’s racism may be a banal document of this comics tradition (alternately coming under “indie,” “alternative,” or “underground”), but his use of racial transference also registers an uncertainty around alt comics’ relationship to labor. After all, the satirical premise here is that Maria uses Deitch’s sleeping body, causing his hand to work “all night long.” The punning between drawing and masturbation oddly acknowledges and elides alt comics’ inability to decide whether making comics counts as labor.

With or without the satirical alibi, these acts of vital/racial transference are key parts of an alt-comics mythos, legible in the analogies between cartoonists and blackness that comics’ largest stars have reached for at various moments. (See the Art Spiegelman-Chris Ware interview in Hillary Chute’s Outside the Box, in which she bafflingly replaces Spiegelman’s apparent use of the n-word with “[terminology].”)

“Moonlight Madness” regards Maria’s racial plasticity––her ability to become white while retaining a trace of Indigeneity––as a source of libidinous energy and subversive edge, loaning brown vitality to white comics. That vitalism makes comics a product of undirected and automatic pleasure rather than creative labor, even though the realities of alt comics sits uneasily between these two poles, and auteur book deals are no less a relation of labor than work-for-hire contracts.

An otherwise unexceptional work by a canonical figure, “Moonlight Madness” demonstrates why questions of power, labor, and distribution are as urgent to the study of “creator-owned” and “indie” comics as they are to that of company-owned superheroes. Precisely because the world of alt-comics has largely disavowed such issues within its own boundaries, its recourse to allegories and alibis of racialized vitality require further attention.

The issue is not purely one of printing racial caricature versus censoring it, as Groth has insisted in public statements. The issue is that the largest arms of alternative comics continue to wield a romantic underdog story against both labor and antiracist critiques without understanding how those racist drawings have been useful to them. In a decade where Fantagraphics books’ US distributor is W. W. Norton and graphic novels have become naturalized into bourgeois literary culture, racist cartoons and their “archival” associations with the twentieth century’s “greatest cartoonists” (e.g. Carl Barks) have likely become more useful, not less. What’s at stake here is a myth making self-identification that has shaped, among other things, the labor practices that this industry can get away with and the histories it has imagined for itself.

Ho Che Anderson and the Sitcom of Blowhards

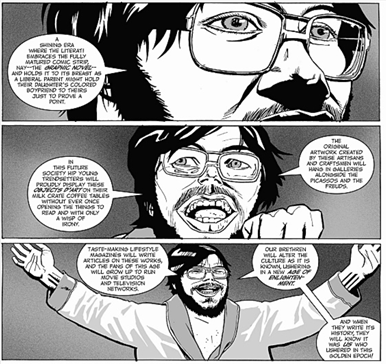

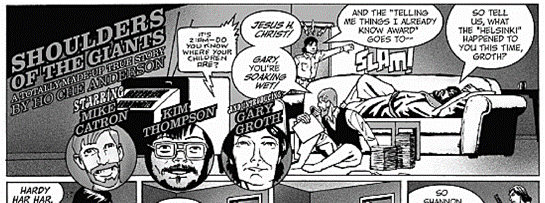

What would comics criticism (and publishing!) look like if it took all this romance with a significantly larger grain of salt? Ho Che Anderson’s three-page comic “Shoulders of the Giants: A Totally Made-up True Story,” a satirical comic that serves as a small opening in the We Told You So narrative, gives us one possible model. In the book, Anderson’s comic comes right before Fantagraphics’ move from Maryland to Connecticut at the end of the 1970s. It dramatizes the historical moment (circa 1977), when Fantagraphics, then only publishing The Comics Journal, received financial respite from its constant precarity through Kim Thompson’s inheritance.

Anderson sets up this scene as a sitcom-esque farce. It goes like this: Gary Groth bursts into the living room where Kim Thompson and Mike Catron are hanging out. Gary’s dripping with beer––he was just dumped for “pontificating”––and immediately begins ranting about his ex-girlfriend, the cramped living/working space, and the other two men, all the while gesturing wildly with his revolver. Mike’s watching reruns of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and prepping The Comics Journals for shipping. When he complains that Gary’s “playing with that thing” (the gun) instead of helping out, Gary responds with a long, tearful monologue:

What’s the point, Mike? We can’t cover our printer bills. Three months from today there won’t be a Comics Journal, the only thing we’ll be publishing are IOUs. And man, I love publishing. […] You think I wanted to break into my old job and use their typesetting equipment? You think I want to work my crappy temp jobs? I’m typing my vitality away in those places and I resent the hell out of it!

Kim interrupts with a proposal. “I happen to have some inheritance money,” Kim tells them. “I could donate, I dunno, five hundred?” Gary immediately talks him up to a thousand, to Mike’s embarrassment. But Gary also wants to know why Kim would be willing to give them his money, and that much of it; when he asks, Kim begins his own pontificating speech, one given far more climactic visual drama than Gary’s:

Maybe I’m mad––but I see a great future for the medium! A shining era where the literati embraces the fully matured comic strip, nay––the graphic novel––and holds it to its breast as a liberal parent might hold their daughter’s colored boyfriend to theirs just to prove a point. […] Our brethren will alter the culture as it is known, ushering in a new age of enlightenment. And when they write its history, they will know it was us who ushered in this golden epoch!”

Anderson draws Kim’s speech spread across a series of three panels that move from a close, tight zoom on his face––eyes shining with hope––to wider and wider shots of his body; in the last one, his bathrobe attire, outstretched arms, and scrunched, oddly flattened face make him look downright deranged. Whereas Gary’s complaints occur within a tight 12-panel grid with much smaller and less realist figures, Kim’s monologue is accompanied with a kind of spatial inflation. The wider panels and tighter view pump Kim up, then deflate him with the sound effect of Mike snoring: a visual whoopie cushion.

The punchline scales back the men to their grody sitcom setting: a living room, a couch, a television. Mike has fallen into an exhausted sleep, and Gary’s only interested in the check Kim is about to write; neither cares about all this hot air. The comic ends with the smaller panels he used on the previous page, with the final panel drawn in silhouette: Kim slumping, the TV blasting an ambiguous laugh track that might belong to either the show or to the comic.

“Shoulders of the Giants,” like Deitch’s psychedelic allegory, is a work engaged in racial satire, and both comics also make a joke of alt comics’ institutional aspirations by mixing idealized and cynical visions of such an arrival. Anderson’s comic is also no less an origin story than Deitch’s, comparing comics publishing’s dreadful past with its potential rise to bourgeois legitimacy. But the relationship Anderson draws between that past and that future is of a different nature. In his comedic history, the financial precarity of the publisher doesn’t look like heroic hardship, and it doesn’t serve the romance of a rags-to-riches plot. “Shoulders of the Giants” plays with scale in a very different way, puncturing the puffed-up rhetoric with a cynical return to form, with the form in question being a TV sitcom. Alongside the circular cutouts that set up the comic’s cast (“Starring Mike Catron, Kim Thompson, And Introducing Gary Groth”), the final panel with its blaring laugh-track exchange (“TED?! MARY?!” HAHAHA) serves as a winking genre indicator. Are these the giants whose shoulders the alt comics scene stands on?

Anderson satirizes Fantagraphics as a workplace sitcom, turning a real-life detail––the team working all nighters with Mary Tyler Moore on in the background––into a satirical gag. Like Mary and her coworkers, the Fantagraphics team is a hapless group working an unprestigious and low-paid media job. Their suffering––typing their vitality away, falling into exhausted sleep––is less proof of pseudo-punk grit or entrepreneurial spirit than it is a banal complaint about one’s working conditions.

Compared to Deitch’s allegory, what kind of satire does this comic present us with? Certainly not one that trades out a labor story for one of exuberant nonwhite vitality; instead, the mundane exhaustion of publishing work is front and center here. Even Kim’s rousing speech is a patently cynical dream that imagines comics’ potential as literal and cultural capital––not a lively art that “even the stagnant, established bastions of art and culture will be forced to recognize,” as Deitch pictures, but as a stagnant object of that same established culture.

Anderson even gets in a quick gag about white self-image, although luckily for these guys, Kim Thompson gets to be in on the joke (the literati will embrace the graphic novel just as “a liberal parent might hold their daughter’s colored boyfriend…just to prove a point”). If Anderson thinks it’s weird that white people in comics do so often conflate their work with being black, this comic doesn’t make a point of it; his reminisces in the book’s interviews are far more affectionate than critical.

What I appreciate about Anderson’s comic is this gesture of deflation, which prompts the reader to consider how Fantagraphics’ rise in status and reach could be recounted differently through different narrative structures. Both comedy and alt comics are replete with self-deprecating laments that are really self-aggrandizements (there’s not so much distance between the self-presentation of Chris Ware or Crumb versus Louis C.K., although the form of their avatars differ), but here the eccentricities of all those involved are made much less spectacular by the sitcom form. The sitcom isn’t a prestigious or countercultural genre, and even Gary Groth’s casual gun-handling takes on a different vibe compared to how it’s presented in We Told You So’s interviews (as proof of a larger-than-life, devil-may-care persona). In this depiction, Gary playing with his little gun reads more like a jab––white masculinity at its most transparently aspirational.

You Did Tell Me So, But Tell Me Again

Shawna Kidman writes in her book Comic Books Incorporated that “storied clashes with censors, the rebellion of the Underground, heated auteurist battles, and renowned cult fandoms … provided an aura of valiant resistance to a medium that seemed assailed, undervalued, and misunderstood.” We Told You So: Comics as Art leans into that “aura of valiant resistance,” making it the upside and the rationalization of a reputation for screaming matches, loaded guns, and miserly contracts. Even the editors’ inclusion of Dennis Worden’s anti-Groth screed gets short-shrift, lost among a sea of affectionate accounts that frequently reference the existence of a lot of loud haters out there and advise you to ignore them.

I wish that Spurgeon and Dean had found it important to account for all those references to late payments and greedy contracts, rather than bracing the publisher’s own branding as an anti-commercial, pro-creator public service. After all, Worden’s most damning comment isn’t his personal attack on Groth, but his assessment that “there is very little money in underground comics no matter what publisher you have, but from my personal experience with eight publishers, FB is the least generous and asks for more.”

Anderson’s fictionalized version of Kim Thompson’s entry into the company gives us one glimpse of what another portrait might be like, one that might deflate all this “valiant resistance” or track the financials with a more purposeful eye. The company’s many moments of near-bankruptcy or debt serve as evidence of the founders’ tenacious energy, their dedication to all nighters, and doing whatever it takes to keep comics alive. I don’t doubt their efforts. This is work,all of it, and the book’s framing does that fact a disservice by turning a complex labor landscape into a battle between effusive vitality and uptight haters.

Even the main sources of Fantagraphics’ cultural capital seem to be missing here, as Rachel Miller observes in her review of the book: “Los Bros Hernandez are periodically mentioned and haunt almost every photograph from conventions to company party shots,” but they and their work “are only featured in one small section, ‘The Varieties of Love and Rockets,’ nearly 300 pages into the volume.” Odd, to say the least. Their multi-decade partnership and friendship with this publisher are the parts of the story I’d like to hear again, differently this time: how has that relationship changed over the years? What did their contracts look like, then and now?

Pretty late in the book, the cartoonist Joe Daly describes Groth as “us[ing] the vitality of a barbarian but applied to the cause of civilization and high culture.” It’s an image that aspires to peculiarity but now feels deeply familiar. When I read it, I think of the bouncing, nude racial avatars Deitch uses to signal comics’ erotic and political liveliness. Deitch’s allegory presents the artist, publisher, and distributor as lovers and peers, energetically doing what they love against a sea of conservatism. But it’s exhaustion that pervades We Told You So and every part of the comics industry, as the recently unionized workers at Image Comics have affirmed.

The romance of “valiant resistance” is a racist, anti-labor, and historically facile narrative, both aspiration and alibi. But Groth gets the final word, and he uses his final pontificating speech at the end of the book––basically an echo of the one Kim Thompson’s character gives in “Shoulders of the Giants”––to repeat it. In his own words: “It was as if we were fighting for our lives––the life of the art form, anyway, we thought, righteously––practically willing comics into becoming a greater, more expressive art.” Although critics, editors, and publishers play an undeniable role in shaping the artistic landscape, laying claim to such expressiveness (such liveliness, such vitality) is no less a capitalist theft of artistic labor than what Stan Lee did at Marvel.

And I still find this phrase, “the life of the art form,” a curious construction, especially when put into relation with other possible ones: “the life of the industry,” for example, or “the life of comics’ artists.” What is that vitality made of, and whose lives (if any) are spent in its vampiric making? As Deitch shows us, alt comics has an odd relationship to racism that both identifies as and against the nonwhite figure, and yet always relies on it to come alive.[1]

Contemporary comics, I’ve found, are in part characterized by an ambivalence toward cartooning’s vivifying powers. They are often suspicious of the demand for flexible, indestructible, and expressive bodies (on and off the page!), and interested in how the banal, exhausting requirements of capitalist work shape both characters and visual form. Richie Pope gives us the anxious dreams of a napping construction worker; Celine Loup draws the bait-and-switch of isolated, unwaged domestic labor. Laura Lannes draws herself as a dripping egg: “the depleted art worker.” In Madeline Miyun’s “Advanced Pain Tube sr300 Pro,” a dystopian premise of pain extraction becomes, unexpectedly but inevitably, a story about monetized grief. I guess it’s not surprising that artists have come to feel a deep apprehension about animatedness (which has always been racialized) as well as a deep suspicion of easy links between politics and art-making. And though that apprehension and exhaustion isn’t a new thing within comics, I’m glad to see so many artists work against the grain of this gruelingly “vital, energetic” medium.[2]

[1] Nicholas Sammond’s history of minstrelsy in early cartooning and animation makes a crucial observation on this kind of racial transference: “even as it depends on the material touchstone of actual African American bodies, the performance of fantastic blackness paradoxically becomes an epitome of authenticity because it is imagined––as if imagination were an act of condensation in which desired qualities––somatic ease, verbal wit, an inherent resistance to unwarranted authority––are located in the ideal body.” 274, Birth of an Industry

[2] Scott Bukatman, The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012), 3.

Works Cited

Bukatman, Scott. The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012.

Chute, Hillary. Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Duffy, Brooke Erin. (Not) Getting Paid to Do What You Love: Gender, Social Media, and Aspirational Work. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Groth, Gary. “Reflections on Banned Books Week.” Fantagraphics Blog, 2015. https://blog.fantagraphics.com/bannedbooksweek/

Hadju, David. The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How It Changed America. New York City: MacMillan, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008.

Kidman, Shawna. Comic Books Incorporated: How the Business of Comics Became the Business of Hollywood. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019.

Miller, Rachel R. (2017) “Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. We Told You So: Comics As Art. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2016.,” Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 42: Iss. 1, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1969

Ngai, Sianne. Ugly Feelings. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Sammond, Nicholas. Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

Spurgeon, Tom and Michael Dean, eds. We Told You So: Comics as Art. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2016.

Tran, Sharon. “Annotation: Sianne Ngai’s “Animatedness” (2005).” Emergentia (blog), 2010. https://emergentia.wordpress.com/2010/09/18/annotation-sianne-ngais-animatedness-2005/

“WE, THE WORKERS OF IMAGE COMICS, HAVE FORMED A UNION.” Comic Book Workers United, 2021. https://cbwupdx.squarespace.com/

Leave a Reply