For me, it all began with Four Color Comics #1309. Oh, I knew who Bernie Krigstein was beforehand. It’s hard to be into American comics for any length of time without hearing the name in hushed whispers, and “Master Race” is in a class of its own when it comes to publicity. But I knew him without knowing him, knew of him. It was a reprint of this, the last comics story Krigstein ever drew, that caught my attention. Republished in black and white, and in a not very flattering size, in The Mammoth Book of Crime Comics, it was a story set in the world of Ed McBain’s popular crime series The 87th Precinct (Four Color Comics would change its subject and creative team with every single issue, the following chapter featured Hana Barbera cartoon characters). Focusing on a mysterious and reclusive painter who, we learn, kills every person he portrays, it’s a truly wild story. Krigstein himself described it as “the most fantastically absurd story that has ever been typed or presented to an artist for a breakdown.”

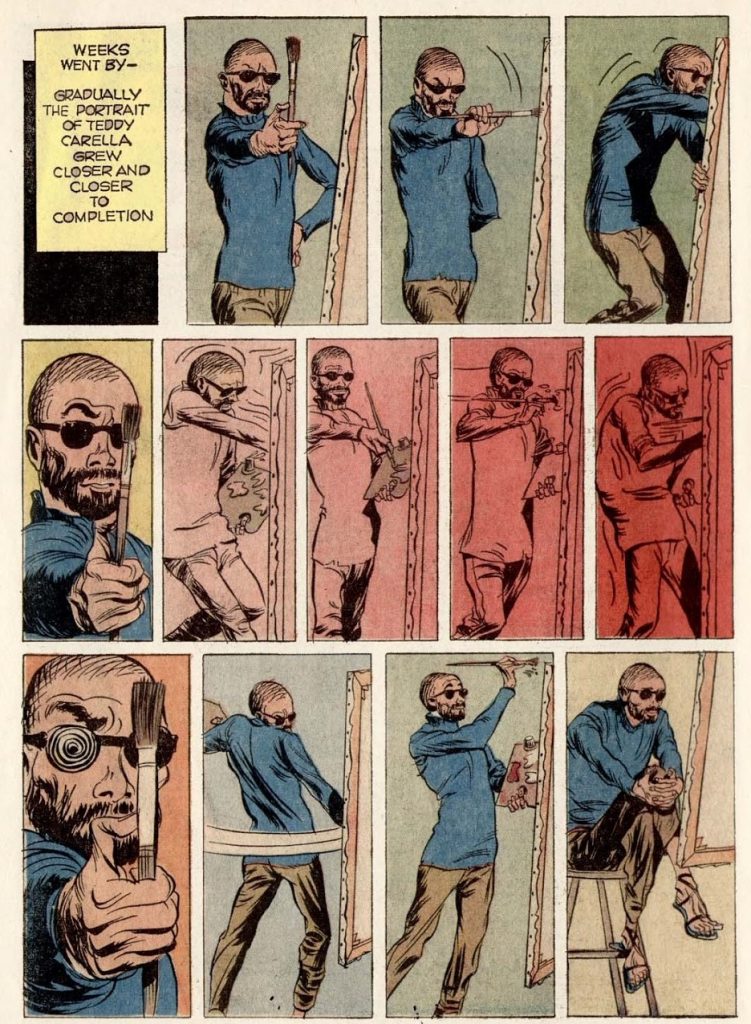

It is exactly this absurdity that gives it its strength, though. The man who was known for his precisely controlled pencils, for his masterful depiction of the body in movement, for his sort of naturalistic approach that could depict the depth of the human spirit without surrendering to cartooning… went all out. In a story about a ridiculous man, an artist at the end of his tether, acting ridiculously. The movements are larger than amateur theater, the eyes bug out (almost jumping from their sockets). It’s a larger-than-life story. It’s also larger than pretty much any other tale in Krigstein’s comics career. At over 30 story pages you can see the artist enjoying luxuries he could barely imagine beforehand – pages with four panels, three panels, even two panels. It’s appropriate, almost too appropriate, to end one phase of his career with a story of an artist who was too good – who could see things no one else could – so good it drove him mad.

Following my encounter with Four Color Comics #1309, I went farther back, looking through old collections and anthologies, finding something quite different. Working on that story was probably almost impossible to imagine for a man who grew used to dividing his own pages ad infinitum in an attempt to wrestle a measure of control over the short stories he was given. Paul Gravett described Krigstein’s work process at his “peak” period thusly: “To make more of them, he reduced the opening image and subdivided each page into smaller and smaller panels. At his peak, he squeezed a record 75 panels into only four pages. For all this effort, the page rate shrank to only $23.” You can see the results of this work in Master Race and Other Stories, possibly the most expected collection in the entire EC Artists Library Line from Fantagraphics. Reading through this collection reveals Krigstein’s strengths as an artist while also showing the limitations of the EC method.

You can see it pretty much every other collection in the EC Artist Library series. Stories are weighed down by the words; the prose sometimes aims for a sort of gruesome lyricism, which can be forgiven even if it often misses, but frequently they simply tell the readers what they can plainly see. More than that, more than words, the stories can be weighted down by the sort of down-to-earth dullness. These are tales of mystery and imagination, whose imagination often seemed limited to what can be visualized in a TV budget. Poor Jack Kamen, a perfectly fine artist in his own right, forced to draw one dull work after another – failing to bring an unimaginative script to life.

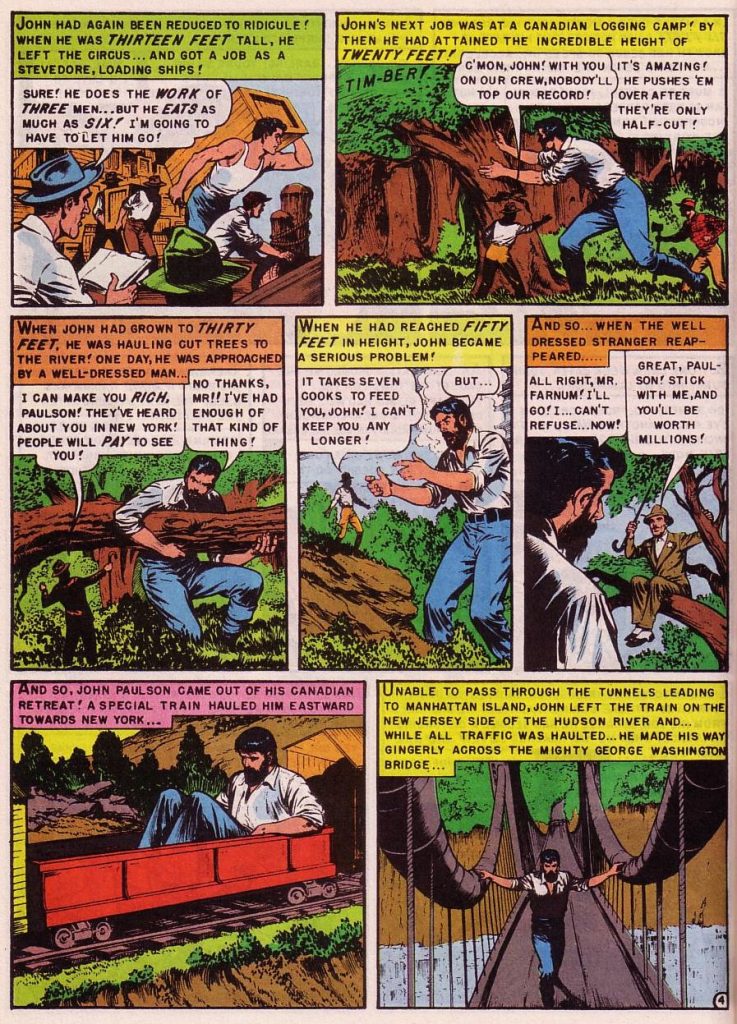

Kamen’s “I Created A… Gargantua!” is a perfect example of the weaker side of classic EC. A story of a giant man wrecking (unintended) havoc somehow appears small and weak. All those cramped panels meant there really wasn’t any room to depict the impact and size of the poor afflicted creature. When he destroys a building, it appears as if he knocked down a model, like a person in a Godzilla costume. His big dramatic end comes in a series of three short panels – he swims into the ocean, a navy commander shouts to shoot him, and then he just disappears from the page. The EC Library had its share of diamonds, but reading these in a big collection in a row can remind you that they are diamonds in the rough.

But… there is something different in Krigstein’s case. Not that the stories are uniformly brilliant. In terms of writing, Master Race and Other Stories has its ups (“More Blessed to Give,” “Key Chain”) and downs (“The Monster from the Fourth Dimension,” “The Purge”); what makes it unique is the way Krigstein works with the inherent limitations and turns them upon themselves. Krigstein stories are, almost exclusively, about people being trapped, being weighted down, being limited. It’s about people trying to break free… and failing at it.

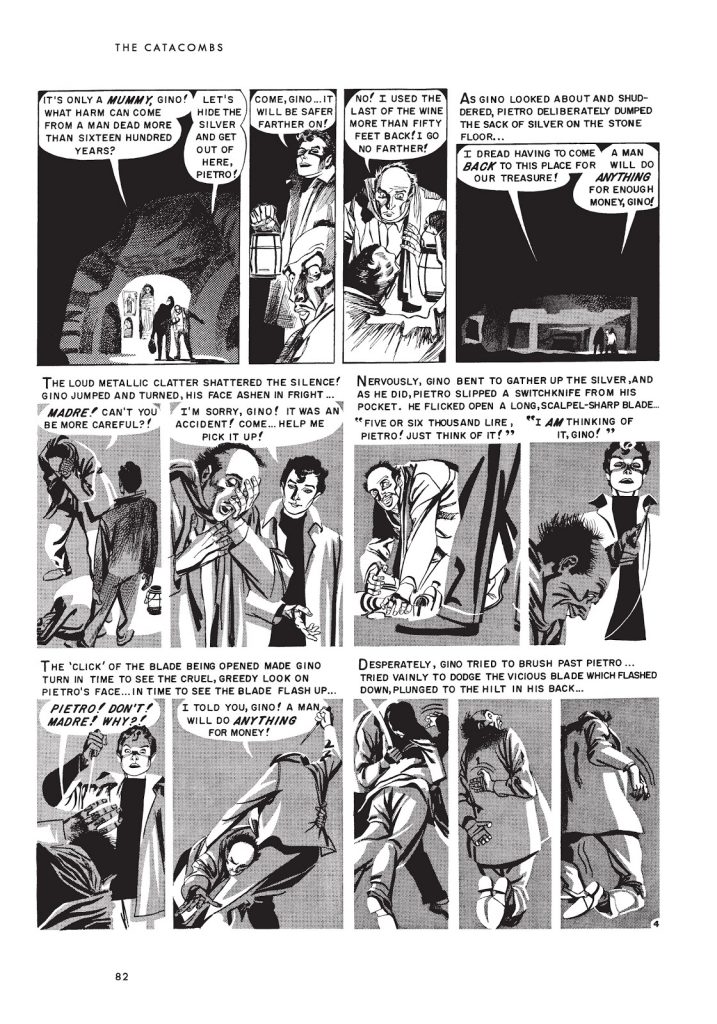

In some cases it’s obvious. “Catacombs” is about people literally being stuck in underground catacombs. It’s a story that plays into Krigstein’s strength, his ability to clearly transfer information to the reader even within extremely small panels, to keep the flow of the story going while allowing a more dense presentation that suits his taste. Note, however, that the choking feeling starts early on before the protagonists venture above ground. The two are constantly shown in tight (closer to vertical than square) panels, even when the action only needs to show one or the other. They crowd one another, we understand. The eventual turn, a man kills his partner, is signaled long before the script made the implicit into explicit.

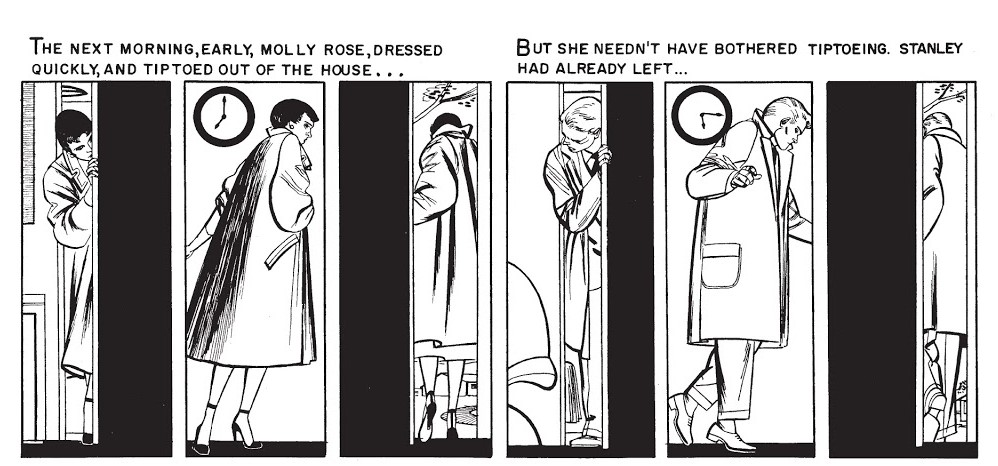

Take “More Blessed to Give” as a different example of the theme of being trapped. This story doesn’t take place in any confined environment. Most of it takes place in a rather lush suburban home, the parts that aren’t are in a rather expensive-looking store. Yet the story needs to show us how sick the married couple are with one another, so sick that they turn to murder, and it does so (again) by dividing the page into smaller and smaller panels, ending with a horizontal line of six panels – depicting the couple hiding from each other, tiptoeing through the house. What’s extra impressive about that scene is the use of blacks as an extra layer of separation, narrowing the panels even further (all of which is done without sacrificing the clarity or losing Krigstein’s sharpness of character expression),

Again, these people are stuck together – they feel choked on an emotional level, and the feeling is what drives them to desperate action. It is the same with the protagonist in “Monotony”. This time the protagonist, Milton Gans, is a prisoner of both his life’s routine and his low-level social class. Greed is a permanent motive in these stories, but not just greed for money – it’s the greed for what that money can buy, for freedom. The final panel of page 6 of “Monotony” features Kirgstein indulging in a rare treat – a horizontal shot that takes up almost one-third of the page. His giddiness with all that open space can only be compared to the giddiness of Milton Gans, who went from a peon to a rich man overnight. So powerful is the art that we can forgive the obvious twist or the rashness in which tale moves from Gans’ lust for life to the punishment phase

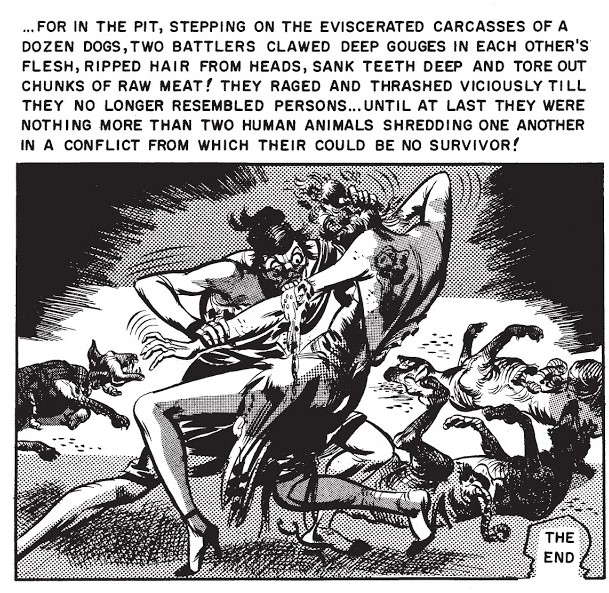

Even the cheap irony of “The Pit,” not to mention the misogynistic script, gains new life with Krigstein’s pencils. Krigstein mentioned once that he disliked Will Eisner: “I think my dislike of Eisner’s work reflected itself in my work!” (The Comics Journal Library: The EC Artists Volume 2), and you can almost see, in your mind’s eye, the version of the story that Eisner would draw – one in which the human grotesque and the animal violence would become one and the same, theatrical histrionics with arms flailing. Krigstein, wisely, goes in a different path. He keeps the exaggeration to facial features, especially those of the women characters who keep escalating their rage. The animal violence is kept to a realistic level, often seen only at a glance (human violence is common in EC stories, but animals are often spared the gaze of the ‘camera’).

Only in the end, in the penultimate panel, does the cartooning reach a crescendo. The two women, snarling, lunging at each other. An evocation, of a sort, of the final line from Animal Farm: “The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.” None of which makes the story any cleverer. Nor does it unmake the sense that the writer really has it in for women (the husband characters end up fine, with the narration noting they “chortled heartily with glee…”). In fact – you can argue that Krigstein heightens the script to a new level of cruelty. These people were really unhappy to be together, they got their “out” in blood and guts. Someone like Kaman would draw it in nurtured fashion, Johnny Craig would make it bloody from page one, Jack Davis would draw it with a wink… only Krigstein could draw it like this, ending with a note of actual brutality rather than a facsimile of one.

And here, I suspect, we come to the reason (or at least a reason) why Krigstein so excelled in these types of stories. In his desperation for more space to practice his craft, he had become just as trapped as his characters. Even for “Master Race,” a story everyone seemed to know was dynamite in the making, he had to beg for extra pages, settling for eight instead of the traditional six. Krigstein turned his desperation inwards, these pages were a reflection of his place in the comics medium – wasn’t he, as well, stuck in the monotonous rot of an extremely regimented industry? These EC stories feel like an outlet for him to express his emotion towards EC, at the comics industry as a whole. This choking, suppressing, limiting industry. Other artists worked within the lines, the precise panel breakdowns provided by the likes of Kurtzman, to a greater or smaller degree of success. Krigstein wanted to create his own lines, and, when he wasn’t given that option, he fought back through his art: here are the people you asked me to draw, these tiny angry people in their little boxes, growing madder each day.

Krigstein’s problem wasn’t that he hated comics (the medium). He didn’t see it as something frivolous, something to be ashamed of. His problem was that he saw it as art, he treated it as art, he was serious as all hell. But the industry didn’t go along with him. It was a product, a high-end product in the case of EC, but a product nonetheless, something to be micro-managed. It was not a place in which the artist could truly express themselves. Back to that issue of Four Color Comics, this ridiculous story, with the final series of panels: at a certain point Rhiner turns directly to the reader and explains that considering the “horrors of the world” he doesn’t really mind his upcoming execution. The eyes, seemingly possessed by something demonic just one page earlier now appear calm, in control, accepting. The artists can finally see things as they really are, free from the dictums of society and the demands of capital. Bernard Krigstein has left comics.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply