Author’s note: Oliver Ristau wrote a piece critical of Red Room: Trigger Warnings #3 and its parody cover of Maus, and that piece got me thinking about the legacy of Maus and the ways that it has been criticized and appropriated in the past. This essay is partly inspired and partly in response to that piece. Enjoy.

When Jim Rugg’s variant cover for the Ed Piskor splatterfest comic Red Room: Trigger Warnings #3: Murder on the Dark Web was released to the public in March 2022, the reaction was swift. The image in question was of two men, bound at the hands and yoked with wood and metal bars formed to look like the heads of mice, overlaid on a background of a pentagram with the Bitcoin symbol inside of it. Cartoonists, readers, and critics (including employees and freelancers who work for Fantagraphics) loudly decried the cover as offensive and called for its removal.

When I say that the reaction was swift, I should note that it was not swift enough to keep the cover off of The Comics Beat, but swift enough that within the day, Fantagraphics had retracted the cover, released a public apology, and Rugg himself had released an apology. The cover in question was a variant in a series of variants where Rugg has been riffing off of the work of other well-known cartoonists; Daniel Clowes (Eightball), Robert Crumb (Zap!), Todd McFarlane (Spawn), and Kevin Eastman (Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles), to name a few. This time, the cover was a parody of Art Spiegelman’s Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History. The obvious difference between Rugg’s preceding variant covers and the retracted Red Room #3 was subject matter; parodying pizza-loving sewer dwellers with nunchucks is one thing, but parodying a cover that portrays two people cowering as they face the systematic state-sponsored genocide of their people is another.

If you want to be lenient, you can say that the cover was a mistake made in bad taste. No matter how you slice it, Red Room is a comic designed to shock your sensibilities, an “E.C. Comics of the modern age,” as Ed Piskor likes to call it, and, so, nearly every page of each book is gruesome. The shock value is the reason it exists, and it exists in a milieu of shock-jockery at Fantagraphics (FUKITOR, Prison Pit, etc.). Secondly, you could note that the variant covers are just a sales device and aren’t a part of the “story” (as much as there is one) of Red Room. Finally, it’s important to note that Jim Rugg apologized and insisted that the cover be pulled by Fantagraphics. Fantagraphics listened, issued their own apology, and Ed Piskor seemingly stayed out of the way. The apologies don’t undo any harm that was done, but they’re a good first step.

Evaluated from a critical perspective, the Rugg cover is an example of a growing trend of anti-Semitic media during a period of openly anti-Semitic harassment and violence in the West. Gun violence at synagogues is rising at an alarming rate, as is anti-Semitic hate speech. We only have to look back a few years to see the Pittsburgh Tree of Life shooting, the plotted bombing of a Pueblo Colorado synagogue, and the Colleyville hostage crisis, and those are just attacks in the United States. Attacks on other minoritized people are also linked to anti-Semitism; the “Great Replacement Theory” espoused by anti-Semitic white supremacists was a stated motivation for the recent anti-Black supermarket massacre in Buffalo, NY. The negative effect of this specific cover by Rugg is especially pronounced given the recent fervor of book bannings in the United States. Maus was recently removed from the McMinn County Schools curriculum in January of 2022, an action that has seemingly been tied to the work of Koch conservative actors as a part of fake grassroots activism against depictions of the Holocaust as well as other major historical and social issues like slavery and LGBTQIA+ discrimination.

Maus is a touchpoint comic, partially because of its notoriety – and this parody isn’t the first. This essay will consider the history of Maus, its entry into (or genesis of) the “comics canon,” the way it has been appropriated in the past, and the dangers of creating transgressive art at the expense of real human suffering.

Maus as Progenitor of the “Comics Canon”

As a cartoonist, Jim Rugg is an artist whose brainstem seems directly connected to his pen. It seems like he draws directly from an unbridled id. This is partially why he’s been able to make such consistently well-drawn books; drawing a lot, regardless of what the “thing” is, is a large part of how you get good at drawing. It’s also why he managed to make a comic book cover for Red Room: Trigger Warnings #3 that would make most people stop and say, “Is this really something I should be doing now?” When Jim Rugg set out to make the Red Room variant covers, it seems that his goal was to homage some of comics’ most celebrated creators. With that thought process as a backdrop for what would clearly become a bad decision, it would make sense to put Art Spiegelman on that list. Maus is, of course, the only comic that has ever won a Pulitzer Prize, it is widely recognized as one of the comics that led to the burgeoning interest in “graphic novels,” and a book that still resonates with readers today.

Spiegelman’s work on Maus, collected in two volumes in 1986 and 1991, catalyzed mainstream academic and lay criticism of comics at large, and its inclusion in the Norton Anthologies established it as the first work of comics in the English literary canon (Chute, 2008; Loman, 2010). Comics are not a new art, but have long been considered “low art,” and their introduction into the classic arrangements of the Western canon has been slow. This is somewhat to be expected, as canon has been largely developed over decades and centuries by critics and “tastemakers,” the vast majority of whom fall into the long-standing category of old white men trying to maintain their cultural power. Canon is designed with a purpose; as Kramnick notes, “the formation of the English literary canon […] was at once a reaction to immediate concerns and a long and complicated process of abstraction (1997, pp. 1088). In the 1700s, the adoption of Shakespeare into the English canon was as much a celebration of his creative use of the language as it was a demanding requirement that a person be “educated” in order to understand the context of his work. Likewise, the development of a comics canon has long been associated with a desire to legitimize graphic narrative as a form worthy of criticism, deep thinking, and celebration (Loman, 2010), and, perhaps, more cynically, as an exercise in commodification — it’s far easier to sell copies of Watchmen to readers who haven’t“bought-in” on comics if Watchmen is considered part of some cultural touchstone.

Regardless of whether the development of the “comics canon” was for critical or commercial reasons, though, it is likely that Spiegelman’s work on Maus energized the conversation about comics in critical and literary spheres, leading to a flurry of work in the early 2000s that attempted to establish an American comics canon. The co-hosted Masters of American Comics, curated by John Carlin and Brian Walker, established 15 cartoonists as leading voices in that charge, which included Spiegelman alongside cartoonists like Herriman, Caniff, and Schulz (Hammer Museum, 2006). Brunetti offered a similar but distinct sampling of work in his Anthology of Graphic Fiction (2006), and for over a decade Houghton Mifflin released The Best American Comics anthology, which brought comics on the fringe of publication spaces into the discussion of the canon (Moore A.E et al., 2006-2019). Maus has roughly been centered throughout this era; it is the most cited, most written about, and most reviewed piece of graphic work in comics, in academia, or otherwise.

Criticism, Appropriation, and Parody

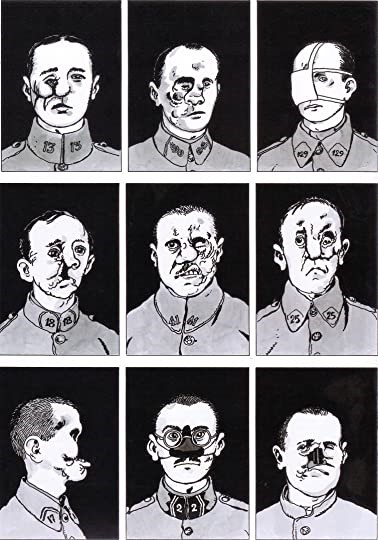

Theriomorphism & Katz

While Maus has been lauded by scholars and critics, it has likewise received its fair share of criticism. Harvey Pekar, in the pages of The Comics Journal, had a variety of concerns about the work, including Spiegelman’s characterization of his father, Art Spiegelman’s reliability as a narrator, and of Spiegelman’s use of animal heads to categorize his characters (1986). This theriomorphism is used to classify nationalities and ethnicities; Jews are presented as mice, Nazis as cats, Poles as pigs, Americans as dogs, and so on. Pekar’s contemporaneous review criticizes this central conceit of Maus as “clever for the sake of being clever” (pp. 55), but other critics have gone further, saying that Maus is either fatalistic (Halkin, 1992) or that it deals in the sort of essentialism upon which the Nazis themselves built their horrid genocide (Pullman, 2003).

Ilan Manouach has criticized the theriomorphic component of Maus in a more direct way, with his graphic détournement titled Katz, in which the entirety of The Complete Maus is reproduced, except that all characters are given the heads of cats. Katz was published in 2012 as a criticism of Maus as Spiegelman presided over the Angoulême International Comics Festival. It effectively hijacked the original text to make a point about the polemics that Spiegelman uses throughout Maus. Jews are not mice and Germans are not cats, but, rather, humans are humans. In conversation with Kartalopoulos, Manouach notes:

“The reasons that I did it were first to give life to Maus and to understand it well, and second in order to question things that have already been questioned regarding this work, this naturalization of the characters that finally promotes a very essentialist reading of history, which is very, very problematic now. And it shouldn’t just be a footnote in Maus; it should be the central focus of the work, this problem.” (Kartalopoulos, 2016, p. 45)

When Katz was released in 2012 at Angoulême, the French publisher Flammarion, which controlled the license for the French translation, sued Manouach’s publisher, La Cinquième Couche. Without the ability to defend the work in court, the two parties settled, and what was left of the entire print run of Katz was destroyed. Copies of the book still remain in private collections, and a fully scanned version of the comic is available on the internet.[1]

(Image left: Maus II, pg 42. Image right: Katz page 191)

By appropriating Spiegelman’s text, Manouach states the obvious: Cats did not kill mice in the Holocaust — people killed people. Katz takes a surface view of Maus and its use of theriomorphism, assuming that Spiegelman is not in on the joke, as it were. In Manouach’s eyes, the only reading that Maus can take is that of fatalism. Cats kill mice — that’s just what they do. Halkin makes the same observation in his review: “Why did the Germans murder the Jews, who did not fight back, while third parties like the Poles let it happen?[2] For the same reason that cats kill mice, who do not attack cats, while pigs do not care about either: because that’s the way it is” (1992). Other critics have tried to link Spiegelman’s text to Third Reich symbology, albeit unsuccessfully (Doherty, 1996). If your reading of Maus is that Spiegelman sees the Nazis as predators and the Jewish people as prey, the critique is strident.

That reading, of course, ignores both the structural and textual components of Maus which refute its simplicity. The framing of Maus is purposefully troubling, as Spiegelman readily admits in a variety of essays and interviews (Loman, 2006). But contrary to the assertions of many of his critics, Spiegelman’s inspiration for Maus comes not from Third Reich propaganda or an essentialist view of humanity, but from the history of American cartoons (Spiegelman, 2011). Spiegelman’s initial idea for Funny Aminals, where the 3-page proto-Maus was published, was a comic about racism in America, of a “Klu Klux Kats” and Black Americans represented as mice. This idea came from watching The Jazz Fool (Disney, 1929), a Mickey Mouse short inspired by Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer and The Singing Fool. Mickey Mouse, whose linkage to minstrelsy is ostentatious and obvious (Sammond, 2016), became the stepping stone to what would eventually become Maus. It is reductive to insinuate that Jews are mice, Poles are pigs, and Nazis are cats, and so on — of course it is. But Spiegelman uses this particular symbology in a fashion that recognizes and problematizes American popular culture. If Spiegelman’s symbology is troubling, it is purposefully so. Whether or not Maus’s inherent critique of that symbology goes far enough is another question entirely.

Part of the reason why the argument of Katz falls apart is the way the parody ignores the use of masks throughout Maus. Masks have an inherent power; as Zimmerman notes, “members of communities agree, or collude, to invest masks with the power to transform the identity of the wearer” (2020, pp. 3). Masking throughout Maus complicates the nature of its animal metaphor. In Maus I, Spiegelman uses masks as a way to indicate that his Jewish parents were hiding their identities. These masks are ripped off their faces in the penultimate pages of the first volume. Taking a surface view, the use of masks in the first volume of Maus seems to align with Manouach’s critique of Spiegelman’s work. The second volume convolutes the readers’ understanding of masking — Spiegelman himself appears as a human wearing a mouse mask, projecting his Jewish identity, while other humans don masks to project other nationalities or ethnicities. Starting at this moment, and then iterated upon throughout the second volume, the rules by which Maus I uses theriomorphism are continuously subverted, and the argument of Katz is rendered obsolete. The use of masks, especially as convoluted as they are in Maus II, shows Spiegelman’s perception of identity not as fixed (as Katz argues)but as amorphous and interchangeable. Specifically, by appearing as a human wearing a mask, Spiegelman invites the reader into self-reflection and the recognition of shared humanity (Zimmerman, 2020).

Imitation is the Sincerest Form of Flattery: Jesse Reklaw and the Form of Maus

Perhaps because of its notoriety, or because of Spiegelman’s easily-identified style, artists have aped Maus for anthologies and mini-comics since its initial serialization in RAW Magazine in the 1980s. Individual reasons to mimic or appropriate Spiegelman are varied but include the desire for a visual “in-joke” that historied readers would recognize, prompts by editors, colleagues, or co-creators to mimic other cartoonists, or themed anthologies based around mimicry.[3]

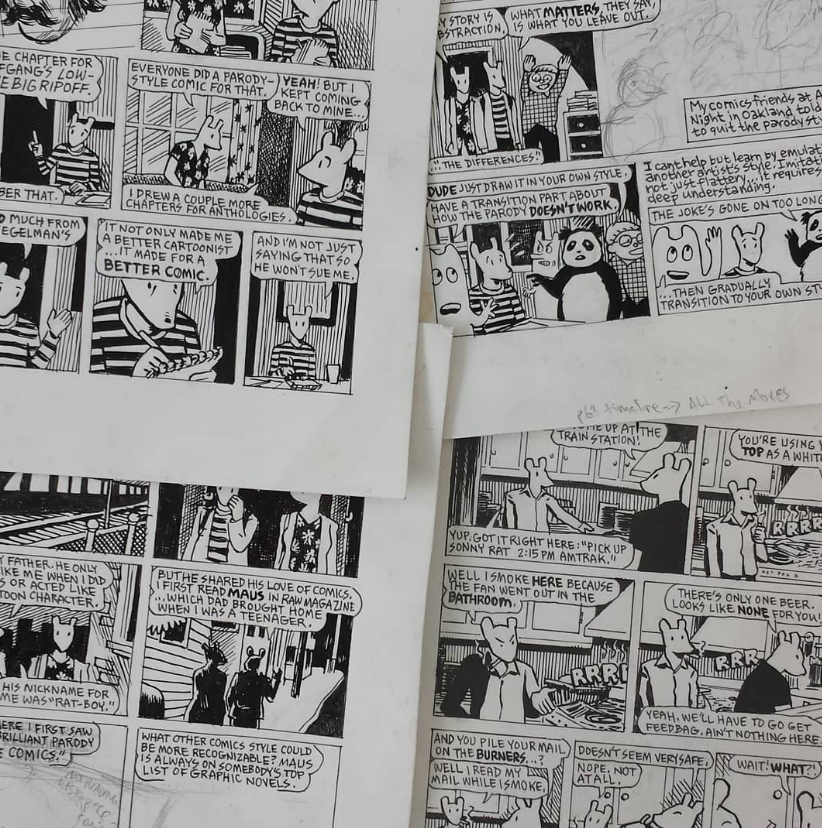

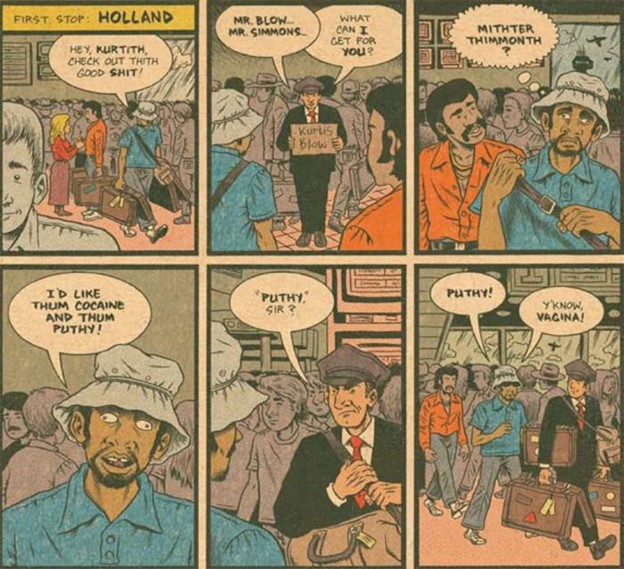

One artist who has repeatedly used the stylistic format of Maus is Jesse Reklaw in his Dealing comics, three of which have been published since the early 00s. Reklaw has published these comics both in anthologies and as mini-comics. The first comic in this series, Dealing: The Big Score, first appeared in a collection titled Low-Jinx #3: The Big Rip-Off, edited by Kurt Wolfgang, in which every anthologized piece had to mimic another cartoonist’s style. Published in 2000, the comic was nominated for an Ignatz award in 2001.[4] Initially published anonymously (all authors who contributed to Low-Jinx #3: The Big Rip-Off were anonymous, likely to protect creators from retribution), Reklaw later returned to his Maus parody and collected three chapters for distribution in a minicomic in the mid-00s. Reklaw, like Spiegelman, is Jewish and (Author’s note, 6/29/22: I believed, based on a few reviews and interviews read during the course of writing this essay, that Jesse Reklaw was Jewish. However, after a further review of his own work, Reklaw recounts in Couch Tag that his mother was raised Catholic and that his father was raised in Christian churches. Apologies for the error.) represents himself and his father as theriomorphic mice, spending time together and discussing the past (sometimes at the chagrin or hesitance of Reklaw the elder). The format of the comics takes a similar structure – Reklaw’s father recounts historical happenings to his younger son, who at times asks additional questions or who writes things down for his work on the comic that the reader is reading. The difference is ultimately in tone – rather than escape from Nazis, Jesse’s father is on the run from the police (illustrated as cats, natch) after coordinating a massive shipment of marijuana from Mexico in the 70s.

In this off-beat way, Reklaw’s work on Dealing critiques Maus from a postmodernist perspective. Unlike Ilan Manouach’s Katz, Reklaw’s critique of Maus is more subtle, and potentially more incisive. Katz, after all, appropriates the ur-text of Maus and converts it into a “new” work that exists only to criticize the original text. It’s a hamfisted approach with hamfisted results. Dealing appropriates Spiegelman’s style in order to tell a much different personal story about drug buying hijinks, military surplus chests filled with bricks of weed, and borrowing money to make a drug deal. It’s a far cry from the horror and the agony of Maus. Dealing, in that sense, potentially trivializes the original text by bringing levity to the work, and, in doing so, questions Maus’ place in the canon and, by that measure, questions the comics canon itself.

While Reklaw’s work in Dealing applies a healthy amount of skepticism to the concept of a comics canon, it’s also clearly evident how much affection Reklaw has for Spiegelman’s work.[5] In unfinished pages of what appears to be a continuation of Dealing sourced from Instagram, Reklaw reflects on his relationship with comics vis a vis his father’s love of them. When his father was buying and reading RAW Magazine, Jesse Reklaw was a teenager reading Maus as it was serialized. Comics, in this way, act as a sympathetic bridge between generations within Reklaw’s work. Comics are a glue that holds Reklaw and his father together, as opposed to Spiegelman and Maus, where the only role comics have in the relationship between Artie and Vladek is a transactional one, where Artie uses his relationship with his father to make art. In this way, Reklaw’s use of comics as a connection between father and son iterates on and even to a degree rebuffs the core relationship of Maus.

Underground Comix, Alternate Comics, and a History of Transgression

At this point, it feels reasonable to return to the beginning of this essay and further evaluate the work of Ed Piskor and Jim Rugg, without whom this essay would not exist.[6] Red Room: Trigger Warnings is a comic that exists to transgress cultural norms and reject traditional aesthetics. This type of comic is a fixture of the alternative comics movement, and Red Room is published by the largest alternative comics publisher in North America, Fantagraphics. But how did transgressive art enter the realm of comics?

The history of the alternative comics movement is intricately tied to the history of underground comix in the United States, a subculture of art-making that thrived on transgressing cultural norms. Prior to the underground comix movement, especially in the 1930s and 1940s, comics became increasingly shocking, provocative, and gory. At the forefront of this movement was EC Comics, which published horror comics in the series Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, and The Haunt of Fear. This changed in the 1950s, as the federal government became increasingly interested in censoring comics. The work of Fredric Wertham entered public discourse, most notably through his book Seduction of the Innocents (1954), which argued that comics were turning young children into delinquents. The industry moved quickly to quell calls for government intervention. Launched in 1954, and active between 1954 and 2001, an industry-wide censor called the Comics Code Authority (CCA) evaluated all comics with mainstream distribution. Publishers would submit comics to the CCA for evaluation and, if approved, were allowed to display the CCA crest on the cover; distributors acted as the de facto enforcers of the CCA and refused to distribute comics without the crest (Doherty, 2022; Sabin, 1996). The CCA was self-enforced as an alternative to government censorship and, at its height, was remarkably effective at keeping “non-code” comics from reaching mainstream distribution.

While mainstream publishers continued to operate under the censors, the 1960s saw the birth of the counterculture, which spread through art into comics through cartoonists like Robert Crumb, Trina Robbins, and Gilbert Shelton (Doherty, 2022). Many of the comics made in this movement were meant to be shocking, transgressing popular norms at the time and focusing on sex, recreational drug use, and music. As underground comix sales flourished in head shops and non-traditional outlets, they were able to exist outside of mainstream distribution and outside of the purview of the CCA. Art Spiegelman’s formative work largely exists in this context; he debuted in the early 1970s as a part of the San Francisco underground comix scene, and contributed to anthologies and magazines including Gothic Blimp Works, Bijou Funnies, Young Lust, Real Pulp, and Bizarre Sex (Witek, 2007).

As underground comix waned and comics specialty stores began emerging in the 1980s, a new generation of cartoonists, including Pete Bagge, Gary Panter, and Dan Clowes, emerged, influenced by the punk movements of the late 70s. Art Spiegelman, alongside artists like Bill Griffith, transitioned from the underground comix movement into the alternative comics movement. Much of Art Spiegelman’s oeuvre falls into this transitional period, with Maus as a potential response to the underground comix being published in the late 70s, which Spiegelman has criticized, saying:

“The flaming promise of underground comix — Zap, Young Lust, and others — had fizzled into cold, glowing embers. Underground comics had offered something new… unselfconsciously redefining what comics could be, by smashing formal and stylistic, as well as cultural and political, taboos. Then, somehow, what had seemed like a revolution simply deflated into a lifestyle. Underground comics were stereotyped as dealing only with Sex, Dope and Cheap Thrills. They got stuffed back into the closet, along with bong pipes and love beads, as Things Started To Get Uglier.” (Sabin, 1996, pp. 118)

Red Room — Shock Jock Shlock

Depending on your point of view, the political aims of the counterculture were either spacious and universal, or largely incoherent. The counterculture’s anti-war, libertarian, and utopian focuses were the most salient of its features, and everything else was whatever the counterculture said it was. Counterculture rejected “the very forms of thought and existence which [had] been created by advanced industrial societies” (Bouchier, 1978, pp. 141). As a tool of the counterculture movement, then, underground comix were indispensable. As transgressive art, underground comix were uncompromising and often extremist in the face of 1960s conservative values. These comics, like other transgressive art, “went too far,” violated enlightened culture, and shocked, disturbed, and subverted conventional moral beliefs (Cashell, 2009). This ethos of “going too far” has largely transferred from underground comix to alternative comics intact, without much in the way of self-examination. In my opinion, alternative comics’ love of “going too far” has more to do with indulgent narcissism and the thrilling desire to repulse and be repulsed, than any political objective.[7]

For cartoonists like Ed Piskor, this is the ultimate goal of transgressive art; to scorn middle-class values and reject institutional aesthetics. The reasons to create such work are intensely varied, and subject to armchair psychiatry, which I will avoid for now, but I will note that critics specifically have a hard time evaluating transgressive art; isolating various components, and looking at transgressive art from a detached perspective, which is the de facto Kantian aesthetic approach taken by most art critics, can lead to the kind of review that the work of Robert Crumb gets — “if you ignore the sexism, racism, and anti-Semitism, the guy can really draw!” This argument is obvious, facile, and, frankly, worthless. But if that’s all the critic can meaningfully bring to the work of Crumb, then it is indicative of the way that transgressive art invalidates the principles of institutional aesthetics (Cashel, 2009).

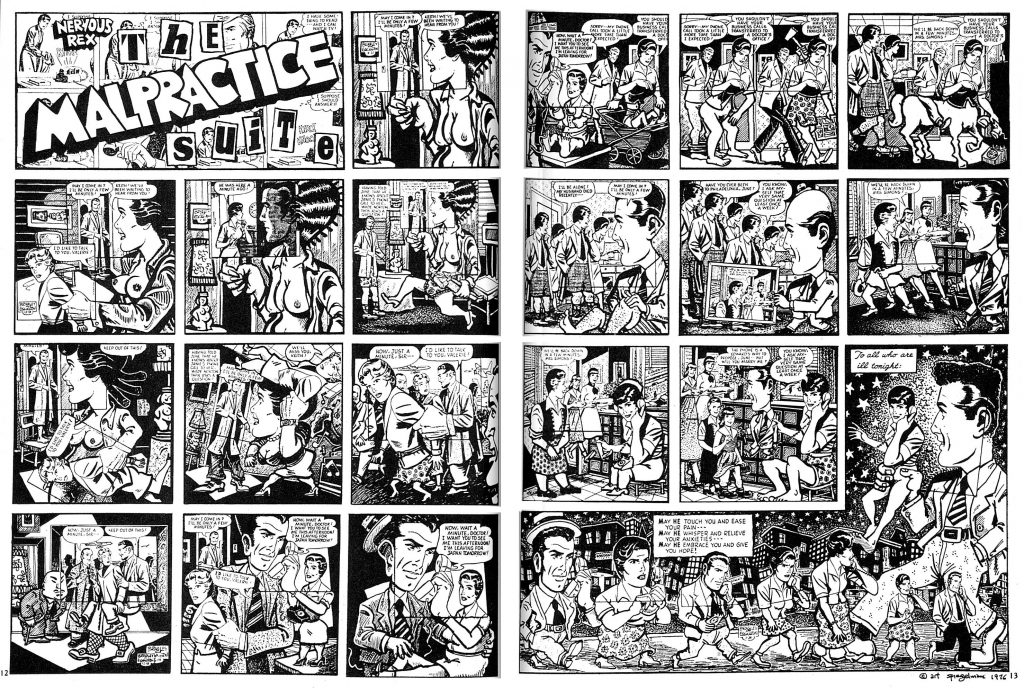

An alternative (and, perhaps, more meaningfully effective) way to evaluate transgressive art is from an ethical perspective; how does the work engage the reader’s moral sensibility? The work of Jacques Tardi in Goddamn This War – Putain de Guerre! (1993) offers a useful example of transgression with a moral purpose. In Goddamn This War, Tardi draws images of men with horrible facial wounds due to injuries sustained in World War I, largely due to the use of new technologies, including machine guns, heavy artillery, and tanks. Men stand for portraits with half of their faces blown off. Even in the military-industrial-media complex we live in, it is a hard image to look at.

The ugliness in the work is clear; the image cannot be described as beautiful, but it does elicit a reaction of revulsion and fear which refuses to operate under a disinterested and detached perspective. The reader’s brain screams, “This is not good!” and some will be inclined to leave their analysis at that place. However, reconsidering the work after that shocking reaction allows readers to come to a far different conclusion; that because of the ethos of the work, the difficult and troubling nature of the project is justifiable (Cashel, 2009). In the case of Tardi’s work on World War I, the transgressions in the work reveal and enumerate the horrors of war. Tardi shows readers the unvarnished and ugly truth of the damage caused by World War I. Tardi’s work, from an ethical standpoint, reveals the pointlessness and bitterness of war (and perhaps, in that way, argues for peace), and is therefore justifiable under this analytical framework.

This is not to say that transgressive art must be instructional in order to be meaningful, but ethical analysis gives readers a framework from which to evaluate transgressive art. What are the boundaries that are being broken, and why? What is the transgression for? And perhaps, most importantly, what does that transgression accomplish?

In the matter of Red Room: Trigger Warnings, the answer to that final question is, “not much.”

For those who have not been fortunate enough to read Red Room: Trigger Warnings, let me give a brief synopsis.[8] A man named Davis Fairfield mutilates and murders a group of women called the “Rat Queens” as part of a dark web murder pay-per-view where viewers tip Bitcoin to the organization that runs the show. The storytelling of Red Room: Trigger Warnings plays out in 3 tiers on the page, top, middle, and bottom, which you follow simultaneously as the reader. The top is the story of Fairfield’s daughter Brianna who is trying to figure out what her dad is up to. The middle is the Red Room broadcast with live commentary from disinterested viewers. The last is the interaction between Farifield and his “boss” the Mistress, who operates the Red Room.

If we analyze Red Room: Trigger Warnings through the moral lens proposed by Cashell or even the ethico-aesthetic paradigm of Reeves-Evison (2020), there’s no motivating ethical factor that can be identified, and at least for this critic, no sense of moral feeling; rather than concern, compassion, sympathy, pity, shame, or guilt, I feel… bored. Piskor is roughly examining the dark web, where “bad things happen on the internet,” but it’s an attempt to channel the zeitgeist. Artwork can generate new values, or problematize existent values, but Red Room does neither. Piskor trangresses for transgression’s sake; he is, for all intents and purposes, taking the piss.

And this is unsurprising, given Piskor’s past; Piskor has admitted to racist caricature in Hip Hop Family Tree, exaggerating Russell Simmons’ facial features and his lisp. His willingness to be transgressive is not new with Red Room: Trigger Warnings. If anything is apparent, Piskor’s desire to transgress is deeply rooted in the status quo of neolibral capitalism; in a video interview[9], Piskor admits that his goal for racist caricature was to attempt to draw Russell Simmons’ ire and thereby promote his comic, a “even bad publicity is good publicity” mindset. In contrast to the goals of underground comix, however nebulous those goals might have been, Piskor’s transgressions are designed to offend bourgeois politeness in order to better attain bourgeois dollars.[10] All of Piskor’s work is “thirsty” — thirsty for commercial success, and, in the case of Red Room, thirsty for “getting a rise out of someone.” Ultimately, this narcissistic craving for naughtiness is an attention-seeking antic, and not some more principled instinct.

And this is the major flaw of transgression for transgression’s sake, especially in comics; as an ethos for creating work, it falls apart when attempting to address issues of race and ethnoreligion (Biber, 2009). Red Room: Trigger Warnings, without any internal structure to rely on for its transgressions, circles back to the bourgeois dollar. Existing inside of the neoliberal capitalist system, attempting to shock people for profit, what Piskor and Rugg end up doing is creating more trauma to be heaped upon the heads of survivors.

Are We Fucking Around, or Are We Finding Out?

By this point, it is probably important to note that I understand that Ed Piskor did not create the Maus parody cover — we can lay that fault primarily at the feet of Jim Rugg. But the milieu of transgression for the sake of capital gain is a breeding ground for the kind of decision-making that leads to the creation of that Maus cover.

Let me do some minor speculation for the sake of making a point — it seems very likely to me that Jim Rugg and Ed Piskor spoke about the various parody covers that Rugg would be working on for the Red Room: Trigger Warnings books before Rugg started working on them. I don’t think this is too far off-base, for a few reasons; First, the two work together on a highly collaborative comics podcast called Comics Kayfabe, and second, they regularly collaborate on other comics projects. Even if Rugg didn’t realize ahead of time that a Maus variant would be offensive, the idea had to get through Piskor, and probably at least one other person at Fantagraphics. The chances that no one caught the implications of the cover whatsoever seems fairly marginal. “Who caught what when” is somewhat beside the point, because given what Piskor has already revealed about himself, we can surmise that… he probably wouldn’t have stopped the cover even if he understood its implications. The pattern from Hip Hop Family Tree speaks for itself. While I have not heard or seen any interview with Piskor regarding the Maus parody cover, he was silent while Fantagraphics and Rugg issued their apologies. Sometimes silence does say multitudes.

But if silence is damning for Piskor, for whom it implies greed and complicity, isn’t silence to Red Room and the Maus parody cover damning for readers as well? That silence speaks to the ways in which we as readers and as critics have desensitized ourselves to the trauma of others, no matter how boring or banal the source material. Perhaps it is the American culture of spectatorship which, as Sontag notes, has “neutralized the moral force of [images] of atrocities”[11] (Sontag, 2004). The boredom I felt when reading Red Room: Trigger Warnings #1? Perhaps, as Wordsworth warned, sentimentality, indecency, and overstimulation have led me to a “savage torpor.” And perhaps, the prurient interest in Rugg and Piskor’s work is worth a second consideration; why are readers so greedy for the pornographic desire to see bodies in pain?

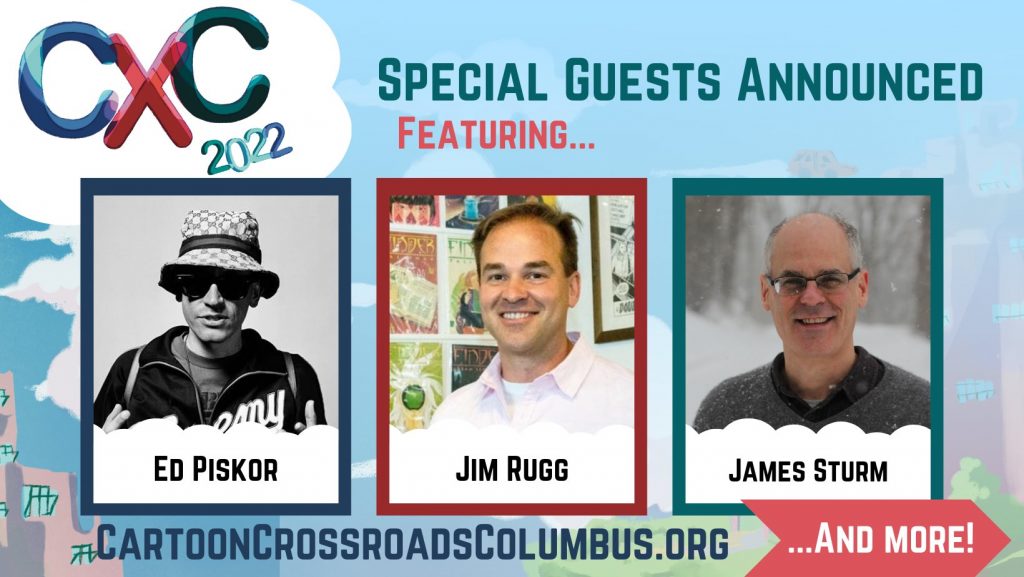

Over the last three months since the Red Room cover was announced and withdrawn and apologized for, much has happened both here in the United States and internationally that is difficult to discuss without again broaching the topic of trauma. Uvalde, Texas; Toshkivka, Ukraine. But the live streams, the TikToks, and the 24-hour news cycle keep beaming it up, 24/7/365. And yet, nothing has changed. The racism in this country is still alive and well, the anti-Semitism is alive and well, and the imperialist war is alive and well, all of it causing immense suffering. I see the same in comics; Ed Piskor and Jimm Rugg are moving right along, recently announced 2022 Special Guests at Cartoon Crossroads Columbus, their images placed in promotional media right beside that of James Sturm, a prominent Jewish cartoonist. People are still buying Red Room as though nothing happened. It seems to me that some of the core themes of Maus — of acknowledging the complexity of human experience, the pain of generational trauma, and perhaps most importantly, the fragility of human existence — are needed now more than ever.

Works Cited

Biber, Katherine. (2009). Bad Holocaust Art. Law Text Culture, 13(1), 226-259.

Bouchier, D. (1978). Idealism and Revolution: New Ideologies of Liberation in Britain and the United States. Edward Arnold.

Brunetti, I. (2006). An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories. Yale University Press.

Cashell, K. (2009). Aftershock: The Ethics of Contemporary Transgressive Art. I.B. Tauris.

Chute, H. (2008). Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative. PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 123(2), 452–465.

Disney, W. (1929). Mickey Mouse: The Jazz Fool [Film]. United States; Columbia Pictures.

Doherty, T. (1996). Art Spiegelman’s Maus: Graphic art and the Holocaust. American Literature, 68(1), 69-84.

Doherty, B. (2022). Dirty Pictures: How an Underground Network of Nerds, Feminists, Misfits, Geniuses, Bikers, Potheads, Printers, Intellectuals, and Art School Rebels Revolutionized Art and Invented Comix. Abrams Books.

Halkin, H. (1992). Maus II, by Art Spiegelman. Commentary Magazine. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.commentary.org/articles/hillel-halkin/maus-ii-by-art-spiegelman/

Hammer Museum. (2006). Masters of American Comics. Los Angeles, CA.

Kartalopoulos B. (2016). Ilan Manouach: Defamiliarizing Comics. World Literature Today, 90(2), 44–47.

Kramnick, J. (1997). The Making of the English Canon. PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 112(5), 1087-1101. doi:10.2307/463485

Loman, A. (2006). “Well Intended Liberal Slop”: Allegories of Race in Spiegelman’s “Maus.” Journal of American Studies, 40(3), 551–571.

Loman, A. (2010). ‘That Mouse’s shadow’: The canonization of Spiegelman’s Maus. The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts, 210-234.

Moore A.E., Madden M., Abel J., & Kartalopoulos B. (Eds.). (2006–2019). The Best American Comics (Vols. 1–13). Houghton Mifflin.

Pekar H. (1986). Maus and Other Topics. The Comics Journal, 113, 54-57.

Pullman, P. (2003, October 18). Philip Pullman on Art Spiegelman’s Complete Maus. The Guardian. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/oct/18/fiction.art

Reeves-Evison, T. (2020). Ethics of Contemporary Art: In the Shadow of Transgression. Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Sabin, R. (1996). Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History Of Comic Art. Phaidon Press.

Sammond, N. (2015). Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation. Duke University Press.

Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the Pain of Others. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spiegelman, A. (2011). Metamaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, Maus. Pantheon Books.

Wertham, F. (1954). Seduction of the Innocent. Rinehart.

Witek, J. (Ed.). (2007). Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi.

Zimmerman, Amie (2020). Maus, Masks, and the Performance of Identity. University Honors Theses. doi:10.15760/honors.843

[1] I couldn’t guess who put it there, honestly.

[2] Halkin’s point here is misleading — the Poles did not “let it happen” as he notes, but rather, they actively participated in the Holocaust, as did many other Europeans under Nazi occupation.

[3] I completed multiple interviews of cartoonists and critics for this piece. These three identified reasons were the most commonly cited reasons, and occurred frequently throughout the 90s and 00s. Second-hand accounts of these comics were easy enough to identify, but finding discrete examples to actually read for this essay was difficult; the history of alternative comics zine-making and distribution of this time period is poorly cataloged for the public record, despite the sustained efforts of zine librarians and collectors.

[4] In 2001, the annual Small Press Expo and the Ignatz Awards were cancelled due to the 9/11 terror attacks, which occured weeks before the show was to be hosted. None of the books nominated in 2001 received an Ignatz Award, keeping this anthology out of wider popular renown.

[5] The same cannot be said of Ilan Manouach.

[6] A dubious honor, to be certain.

[7] I largely believe the argument of “free speech,” which is often used as a justification to make transgressive art, is actually just the excuse artists give when they make transgressive work, and I suspect that if given the opportunity, most creators of transgressive comics would agree. Those that claim that current transgressive comics are for satirical purposes, or to “hold a mirror up to society” are mostly just calling it in. Johnny Ryan is a lot of things, but one thing he is not is a modern day Jonathan Swift.

[8] While Red Room is perhaps one of Fantagraphics best selling floppy comics in recent memory (a promotional statement I have not verified), it strikes me as a middling and largely unimportant comic (sans the Maus embroglio). As a critic in the Kantian perspective, I can acknowledge that Ed Piskor is a solid, if not exemplary drawer. His line, figure, and panelling are effective, although they play heavily on stereotypes and tropes. In contrast, the storytelling, character writing, and plotting are boring, predictable, and affectless. I suspect that most people reading the book are doing it for the thrill, and not because it’s a compelling comic.

[9] Culture Vulture Ed Piskor aka “Eddie p” admits to racial caricatures in “Hip-Hop Family Tree”

[10] And, as Helen Chazan rightly points out, Piskor’s work is designed to remind bourgeois dollars of when they used to offend bourgeois politeness.

[11] I am appropriating Sontag’s text here – the word she uses in her book is “photograph,” but I would argue that the illustrated image has similar power. She notes the same with war reportage of the US Civil War, but, as those who have read it know, Regarding the Pain of Others is a book about photography, not about shock jock comics.

Leave a Reply