Last year, Art Spiegelman’s Maus was removed from a Tennessee school district’s eighth-grade curriculum, a move that generated international headlines and fostered widespread condemnation. What shocked so many about the now-infamous Maus ban was not simply that it happened, though this was outrageous enough; it was also the unserious and disingenuous nature of the McMinn County school board’s justifications for suppressing a book that deals with the state-sponsored genocide of European Jews.

While the school board never explicitly called Maus “obscene,” relying instead on euphemisms like “inappropriate” and “objectionable,” they still invoked the specter of illicit and salacious illustrations; one board member, apropos of nothing, remarked that Spiegelmen had done “graphics for Playboy,” while another argued the entire curriculum was “developed to normalize sexuality, normalize nudity and normalize vulgar language.” Ultimately, board members based their decision to remove Maus on the presence of a few minor profanities and an image of partial nudity. In doing so, they averted their eyes from the only actual obscenity in Maus: the atrocity that is the Holocaust.

In her introduction to Maus Now: Selected Writings (Pantheon, 2022), scholar Hillary Chute provides a lucid analysis of exactly this problem:

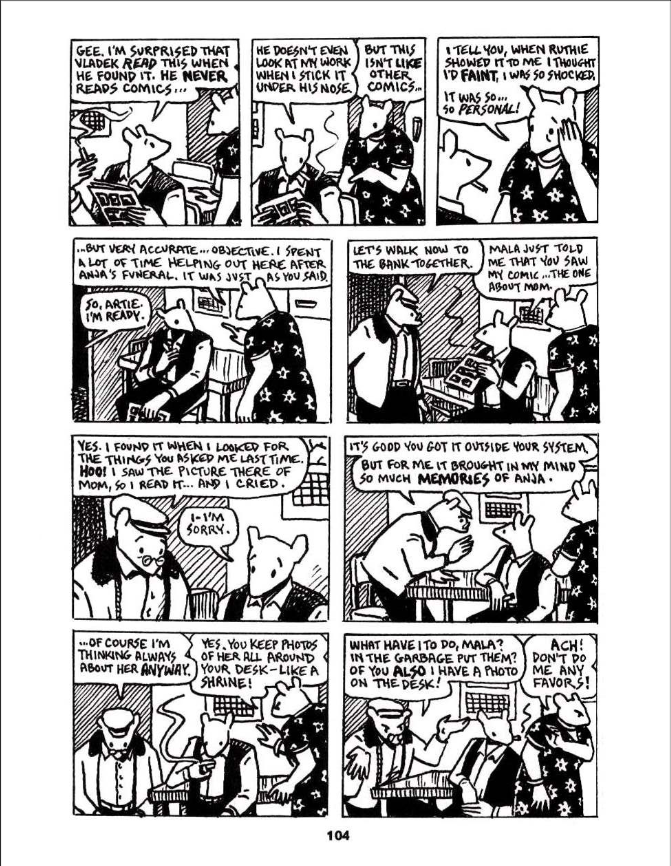

Part of the outrage the ban provoked has to do with the school board’s official, and seemingly flimsy, reasons for removing it from the curriculum: bad language (such as ‘bitch’ and ‘Goddamn’) and nudity (specifically, one small image of Spiegelman’s mother Anja, drawn in human form, in the bathtub after taking her own life, a profoundly troubling visual on which to pin the charge of obscenity). These aspects of the book, while debatably not ideal for an eighth-grade audience, feel beside the point in a testimonial narrative that bears witness to the genocide of the Holocaust: a pretext.

Maus Now, which Chute edited and to which she contributed an essay, includes reviews of Maus originally published in mainstream venues like The New York Times and The New Republic; academic criticism from a range of disciplines, including literary studies and oral history; and other responses to Spiegelman’s comic dating from 1985 to the present.

While the book constitutes an effective counterweight to the tortured reading skills of Tennessee school boards, the McMinn County ban is only one of many current events on Chute’s mind. Amidst the ongoing intensification of racist and antisemitic violence in the U.S., including the white supremacist march in Charlottesville and the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, Maus serves as “a text of resistance.” This is not because the book provides any practical guidance on how to survive a fascist regime, but rather “because it constantly does the work of particularizing victims and survivors alike, working against the caricaturizing impulse despite its prominent animal taxonomy.”

One could, as Chute does in her introduction, describe Maus as “timeless.” But this doesn’t seem quite right to me. It’s more like Maus is time-bound to whatever moment we presently find ourselves in, unable to pass into publishing history and never allowed to become just another “classic.” From this perspective, the essay collection’s title, Maus Now, can be read as both a command and a description: Read Maus now, today, but also notice the way its artistic priorities are continually renewed and validated, year by year, decade by decade, a state of affairs best encapsulated by Spiegelman’s witticism: “Never Again and Again and Again.”

Still, what keeps me (and I suspect most people) returning to Maus again and again is not a perverse desire to be continually horrified, but the pleasure of encountering an irreducibly complex and formally rich comic that rewards intensive study. Part of what makes Spiegelman’s opus continually relevant is its refusal to be fully understood or neatly categorized. Even Chute, who has been writing and thinking about Maus for over twenty years, admits she doesn’t feel like she’s “definitively ’solved’ the question of why it works so well.” What emerges from Maus Now is a portrait of scholars and critics struggling their way toward a collective response to precisely this question: What makes Maus work?

While no writer has a complete answer, the essays do display some common preoccupations, even if they can’t always agree on specifics. Philip Pullman, in a review of the single-volume Complete Maus, deems Spiegelman’s famous visual strategy — rendering Jews as mice, Germans as cats, and so on — a source of inexhaustible disruptive energy, writing that the animal metaphor “is what jolts most people who come to it for the first time, and still jolts me after several readings.” On the other hand, Adam Gopnik, the prolific New Yorker essayist, evinces the opposite reaction, arguing that “the homely animal device” is “so potent precisely because it seems, at first, so disarming.” Is Maus unassuming or shocking? Perhaps the answer is, it’s both.

For some critics, Maus has value for the radical challenge it poses to other art forms and documentary modes, especially those that grapple with the ethical dilemma of representing genocide. As Michael Rothberg writes in his essay on Jewish-American identity and mass culture: “Not simply a work of memory or a testimony bound for some archive of Holocaust documentation, Maus actively intervenes in the present, questioning the status of ‘memory,’ ‘testimony,’ and ‘Holocaust’ even as it makes use of them.” Oral historians also have a unique resource in Maus, writes history professor Joshua Brown, because of the way Spiegelman’s schematic cartoons stimulate the imagination without dominating it, allowing readers to engage with a material representation of history that doesn’t claim absolute fidelity to reality.

Fortunately, little energy is spent litigating Spiegelman’s choice of medium in this volume. Chute observes in her introduction that when Maus first appeared, “some readers struggled with the perceived glibness of connecting comics and the Holocaust,” but this sentiment is mostly present as a figure for enlightened critics to spar with. Kurt Scheel, a German scholar whose 1989 review of Maus was translated into English specifically for inclusion in Maus Now, provides the most devastating blow: “Whether comics can be art is a question that those who know nothing about comics like to ask.”

This is not to say, however, that all the critics are equally skilled at reading comics. While Gopnik provides sophisticated insights into the history and nature of cartooning, his critical discernment is stymied by the apparent simplicity of Spiegelman’s cartoon figures; Gopnik’s assessment that Maus is “considerably less daring, as drawing and design … than much of Spiegelman’s own earlier work” is undermined by more astute observers of the comics form, including Chute whose essay focuses on the way Maus’s innovative use of formal structure literally brings together past and present on the space of the page.

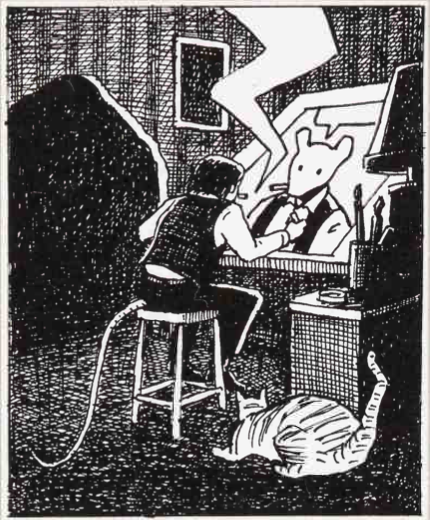

My reading of Maus Now (and the writing of this review) was slowed by the number of times I had to turn back to Maus to confirm some observation I’d never noticed before. Chute points out, for example, that the short comic, “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” (which tells the story of Spiegelman’s mother’s suicide) is flanked, on the pages before and after, by a deliberate series of panels featuring a conspicuous wall calendar. Chute reads the calendar icon as a “representation of the linear movement of time.” It is then “disrupted by the intrusion of ‘Prisoner,’ which does not seamlessly become part of the fabric of the larger narrative but rather maintains its alterity.”

To this critical insight, I would add the following interpretation: The calendar itself, with its arrangement of boxes on a page, can be thought of as a kind of alternative, comic-adjacent form. But where a calendar represents a rigidly structured method of ordering time, Maus rips up and refigures the notion that temporal organization can ever be clean or tidy. Simply listing dates on a calendar is an insufficient method of history, Maus suggests. This is clearly true when documenting traumatic history on the scale of the Holocaust but also for personal cataclysms, like Spiegelman’s mother’s suicide — a tragedy that, to further complicate the narrative, is not unrelated to her experiences in the Holocaust.

This kind of reading experience — the continual reminder that every penstroke and composition decision is deliberate — is my personal, inevitably partial answer to the question of why Maus works. While Spiegelman’s comic can certainly be accused of breaking boundaries, Maus Now makes clear that its power is not merely transgressive. Instead, Maus is permissive: Even now, decades after it was first published, the comic continues to grant its readers permission to find new reading strategies and to see new possibilities for the medium.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply