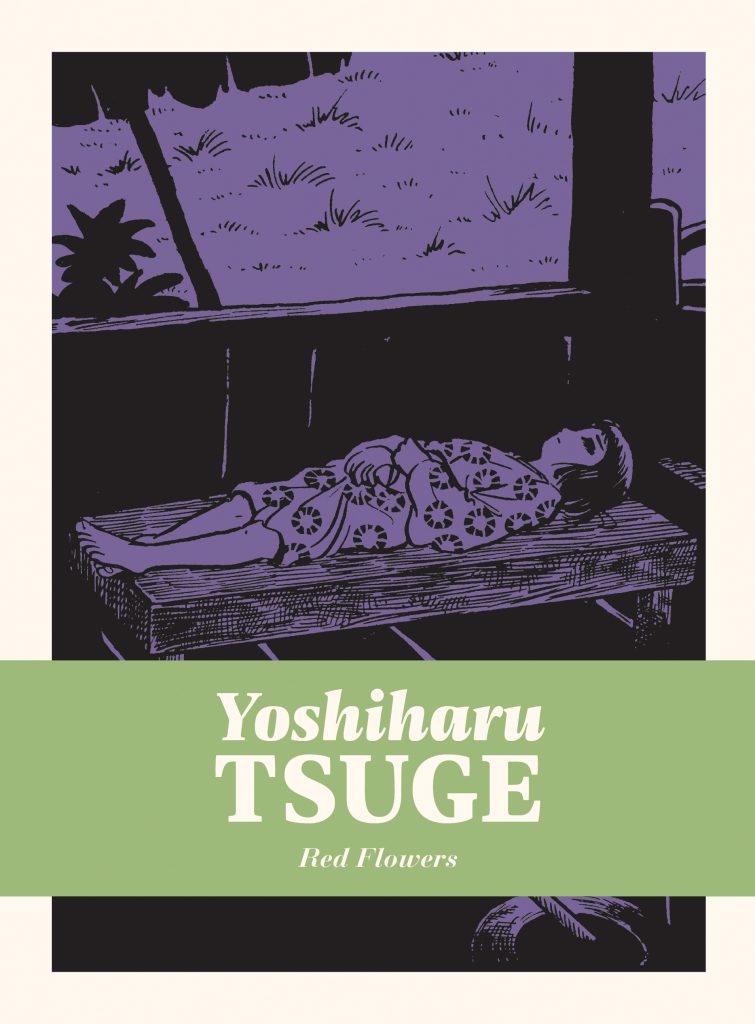

Red Flowers is the second collection in Drawn & Quarterly’s Yoshiharu Tsuge Library, collecting stories originally published in 1967 and 1968. Like the previous volume, it’s translated by the esteemed Ryan Holmberg, who also provides the closing essay with Mitsuhiro Askawa. Also, like the previous volume, it’s a strong contender for the best book you could read this year, and it doesn’t really matter which year you happen to pick it up. The Swamp, the first collection in the series, was already a brilliant work in its understanding of human foibles and canny cartooning, but Red Flowers manages to leave it far behind.

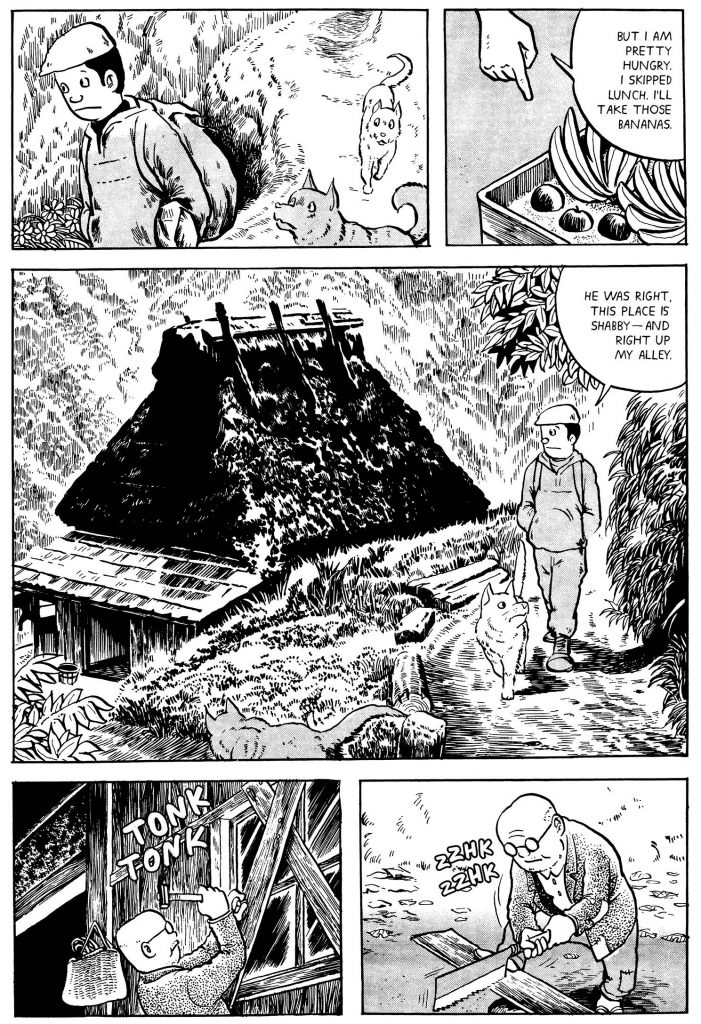

The first thing one notices when opening the volume, leafing through it randomly, is the way Tsuge illustrates nature here. While his human figures remain extremely cartoonish, both facial features and body favoring expressiveness over anatomic precision (the trio of young hooligans in “The Ondol Shak” are a particularly glaring example), his drawing of backgrounds and natural scenery grows ever more precise. Shots of forests, seas, rivers, ponds, deserts, crumbling sheds, and old temples fill these pages (while scenes taking place in large metropolitan areas are almost completely absent).

Tsuge can evoke the proper sensation of outdoor space with a few leaves of grass rustling in the background or the absolute greyness of a cold day at sea. His architecture is marvelous – not because he draws impressive buildings, but because he draws the most shabby of constructed spaces, dirty and small, with the same amount of interest other artists would only give mighty vistas. If Tsuge draws it (‘it” could be anything and everything), it’s because he cares about it, and if he cares about it, he can make you care as well.

These images are all beautiful in their precision; every line is counted towards something in building up these environments. Never in a manner that overwhelms the eye with its details, the backgrounds exist apart from the human (and non-human) figures inhabiting them, but the existence of the figures gives these same environments meaning, putting them in an emotional context. Yet, when I say “beautiful”, I am not referring to the polished beauty of commercialization or to the heightened sunniness that can be seen in works like Taniguchi’s The Walking Man. Rather, Tsuge’s nature is often small, cramped, broken, blemished, dangerous. This is what Askawa and Holmberg refer to as the wabi-sabi (an appreciation of imperfectness) in their essay. Tsuge isn’t afraid of what others would consider ugliness; he doesn’t see it as a blemish but as part of nature (and of human existence). To paraphrase Tolstoy – beautiful places are all alike; every ugly place is ugly in its own way.

As much as this is a collection of stories, it’s also a collection of images from Japan of the 1960s, and it can give you the same sensation of exactness as Joyce did to Dublin with Ulysses. You got to love something — to understand it completely — to paint it with all its flaws in such a manner so the flaws become not something to be sanded away but an essential part of the picture.

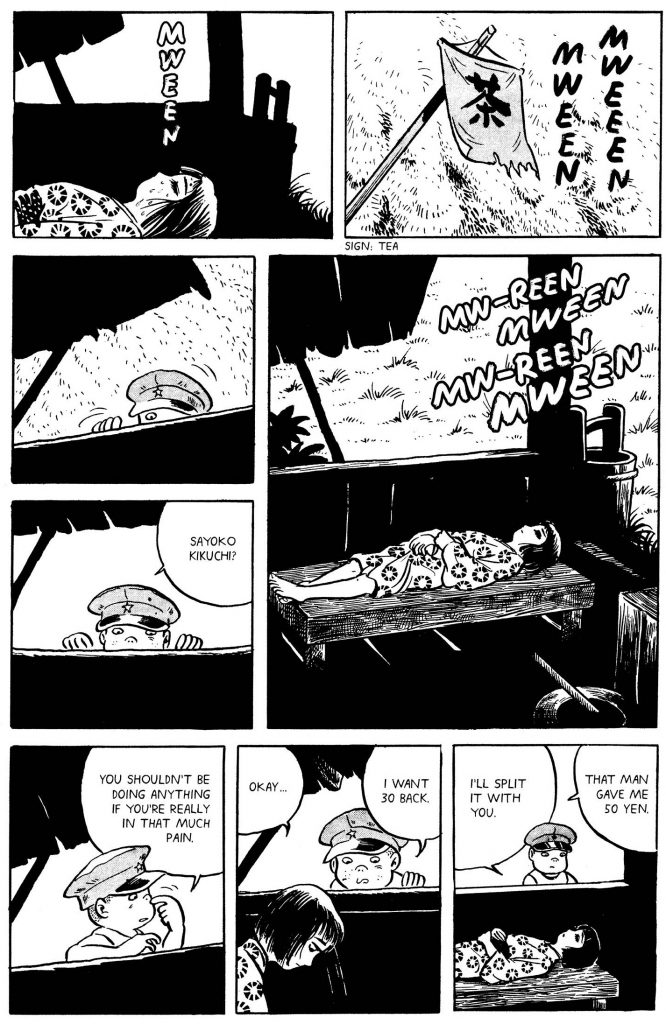

The ugliness Tsuge draws and writes nature is often a way to communicate “uselessness,” a rejection of human desire to achieve capital. Several of the stories focus on would be travel-destinations to which an outsider figure drifts in with a suggestion on how the people inside could make more cash. By changing things, the stranger figure wants to sand away at the imperfections, failing to grasp their importance. For instance, in “Mister Ben of the Honyyara Cave”, a layabout comic-book artist meets his mirror image in the tourist industry – an older man constantly grumbling about how the neighbors make more money with their large pools of expensive fish. Yet the same older man would never develop his Inn and territory in the same manner. The story or characters never stop to say it, but it’s clear that neither of the characters is going to hustle their way to success, nor are they going to fall into holes of personal misery. These people are; the stories Tsuge draws and writes here are not about transformations but about states of being.

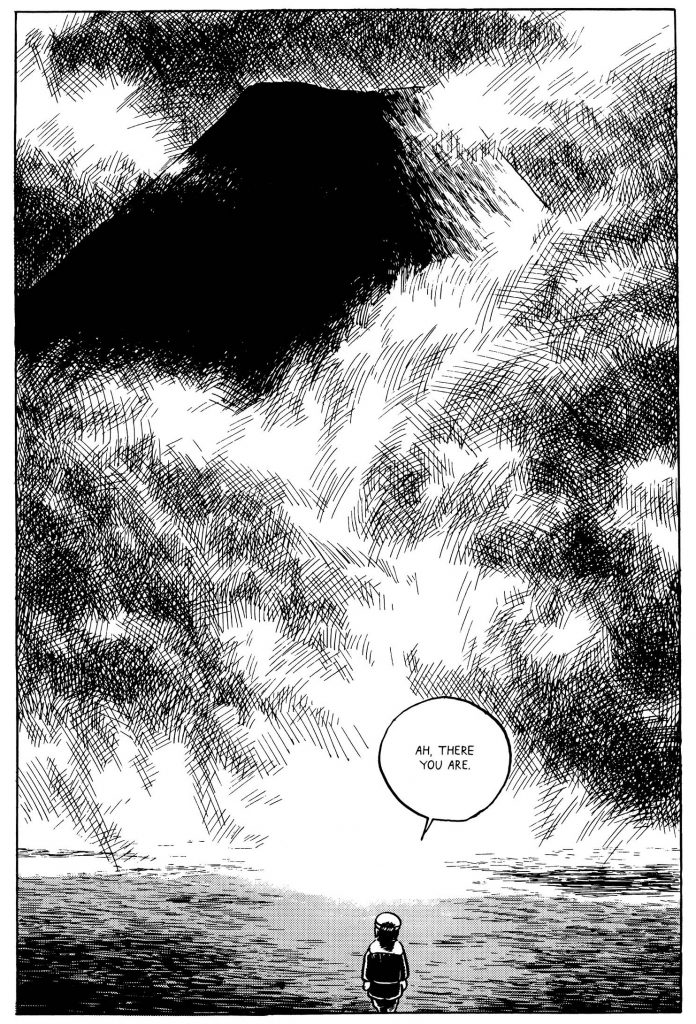

The other recurring element throughout the stories also relates to nature. Just as people find it impossible to comprehend it, constantly wonder about ways to exploit it, so too do they have trouble understanding other people. It’s not that the stories are riddles — all the events are pretty clear cut — it’s the way they refuse to “solve” themselves in some clear character arc. As an example, the developing relationship between the hesitant man and the designer woman in “Scenes from the Seaside” appears to be going towards an obvious direction — a budding romance, a sense of personal revelation, the man coming out of his shell — but the story leaves them before any of that could happen. These are just scenes, not a life story, a mood rather a conclusion.

The ending of that story, a rare two-page spread in the collection, shows the man swimming away from the woman, his body now a mere shadow as the grey weather ominously hangs above, as rain continues to drop. It is achingly beautiful in how cold and miserable it appears; the way Tsuge captures the sensation of greyness and cold goes through the skin and into the bones. Yet, still, it is a coldness that nevertheless cannot detain the two from meeting and conversing.

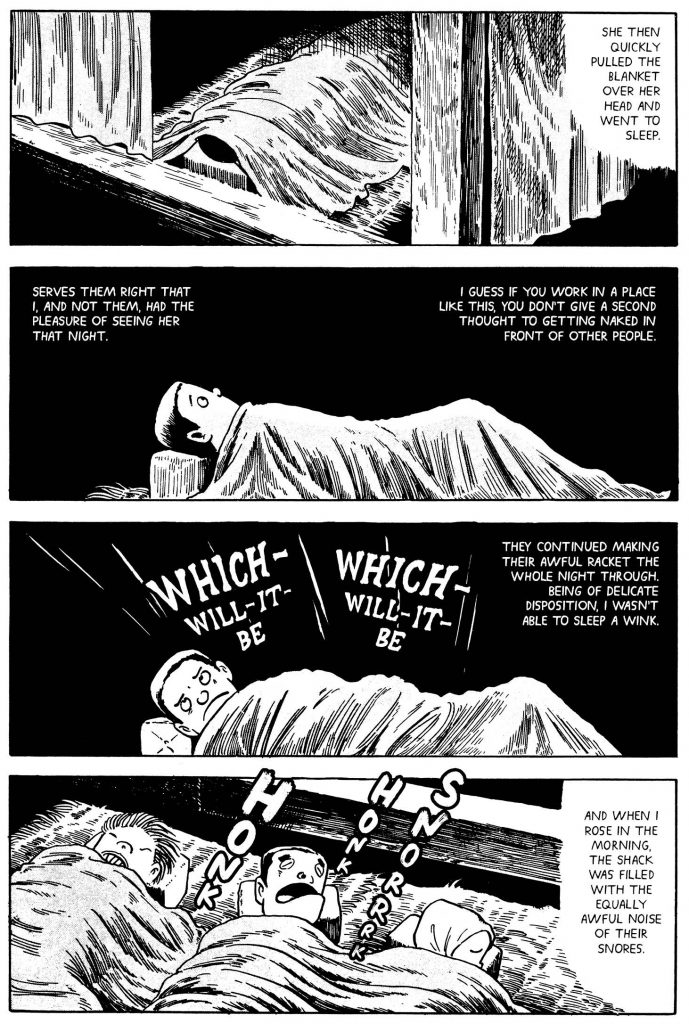

Throughout the book, stories seem to be setting up a “main character” only to reject the notion and change their focus. “Red Flowers” opens on a traveling fisherman, a traveler who appears in several names and guises throughout Tsuge’s work, only to leave him aside in favor of a young girl going through puberty. Likewise, the narrator of “The Ondol Shak” slowly gives way in favor of a trio of annoying youths. Having established a sense of time and space, Tsuge allows his gaze to wander to and fro. The narrator’s developing hate for the youths is part of his inability to understand them, his forgetfulness that he probably was very much the same when he was a younger man.

“Salamander” (inspired by a story from Masuji Ibuse) is notable in this collection for not featuring a single human character. The story focuses on the titular creature who gets stuck in a cave of sorts after growing too big to leave. Unlike Ibuse’s story, which ends up centering on an argument between the salamander and a frog (allowing the two beasts to talk on equal terms), the salamander in Tsuge’s version has no one to talk to. A truly lonely being that has to define his world for itself.

There are elements that would mark this story as horror – the sewer space that becomes the new home is dank and confusing (at least at first), a labyrinth; the backgrounds are almost completely black (as opposed to dominant white open spaces of other tales), we can see mounds of garbage. Yet, for all of these surface pieces, the story does not aim to terrify or disgust. The salamander, lost at first, learns to think of the place as a home.

In the creepiest scene in the story, as creepy as any you’ll find in fiction, the salamander encounters a floating body of an infant child. We are never told how the body got there, no hints or revelations follow, it’s simply another thing that floats by and eventually disappears. The salamander, unlike the reader, isn’t even aware he has encountered something spectacular (even if spectacularly gruesome). It cannot comprehend beyond the limits of its perception. And, in that manner, it is not different from the human figures in the book.

Nature, in Tsuge’s work as in life, can be ugly or beautiful or both, but whatever it is – it exists apart from us. Our perceptions only give nature meaning in our own eyes, we do not change what exists (unless we intervene to “develop” and “improve,” which quickly becomes “destroy”). The world exists apart from us and will continue to exist after us. The salamander doesn’t care, it doesn’t view the human dead with any more reverence than any other piece of floating garbage. That which you might see as an insult for humanity, Tsuge might as well see as proper appreciation for the floating refuse – beautiful in its imperfection.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply