In a reconcilable contradiction, body horror as a genre often seeks to shape and give tangible form to incorporeal psychological turmoil, which can feel more painful and injurious than any physical harm. Laura Lannes’ 2018 comic John, Dear takes this a step further, by imagining the body as a site of total self-abnegation, indeed annihilation, in the face of an abusive relationship between the narrator and the eponymous John. As the comic progresses, Lannes depicts a woman who, unable to shape herself into the impossible person that John expects, attenuates both physically and psychologically.

The narrator that John, Dear centers on is already untethered from her sense of self by grief over the loss of her mother. Enter John, an “extraordinary” man seeking exactly such vulnerability in a prospective partner upon which to exert a pathological desire for control. The body horror that follows is probably best skipped by trypophobes. Lannes’ narrator begins to develop holes all over her body, hollowing from the inside out to better resemble the lacuna that John wants to fill.

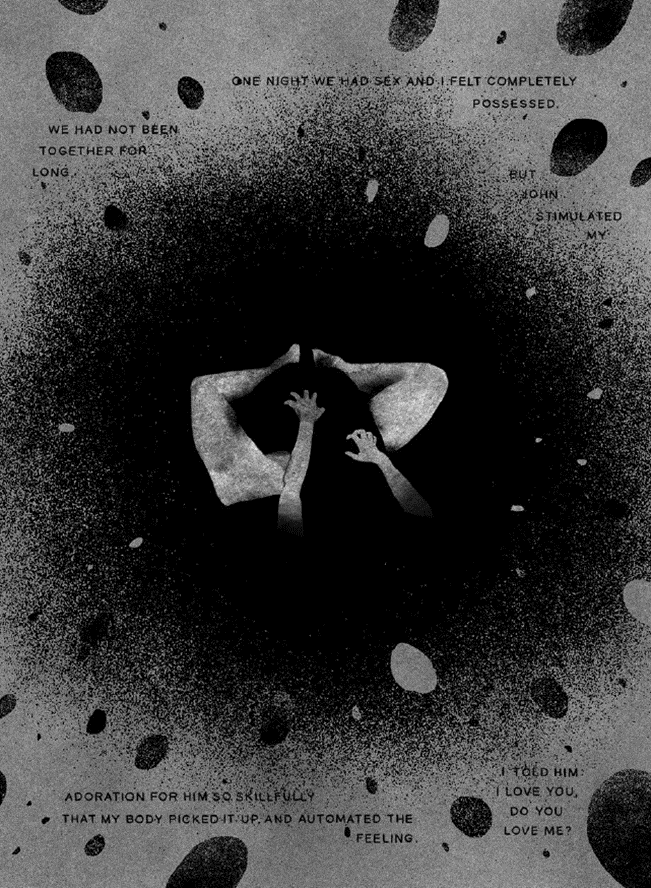

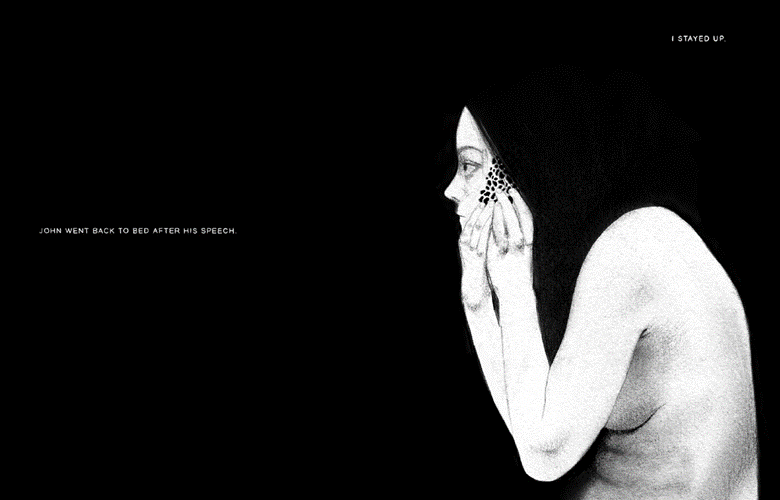

Never has a comic more effectively exercised both the visually suggestive and metaphorically rich possibility of shadow. Early on, as the narrator and John have sex, he’s an inky black negative space, a silhouette upon her prone body that bleeds into the surrounding darkness. The comic’s unrelenting chiaroscuro does away with Lannes’ need for any traditional framing devices characteristic of the form. The darkness, sometimes impenetrably black, other times a grainy charcoal or graphite smog, fosters the intended sense of inexorable suffocation that the reader cannot help but share with the narrator. The comic begs the question of whether darkness is a presence or an absence, and asks which might be considered preferable when the void is looking into you.

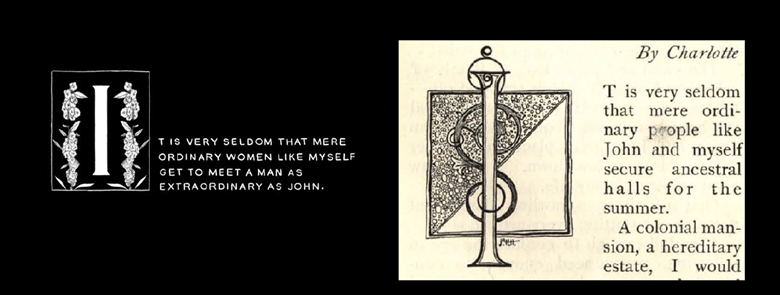

John, Dear acknowledges the debt that Lannes owes to protofeminist antecedents, specifically Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s pioneering short story about postpartum psychosis, The Yellow Wallpaper. Not only does Lannes thank Gilman for “doing it first” in the acknowledgments of John, Dear, but her opening page directly echoes Gilman’s opening lines of The Yellow Wallpaper, from the language itself to the ornate letter “I” that foreshadows impending ego death in both stories.

The Yellow Wallpaper recounts the travails of a woman prescribed a “rest cure” for a “temporary nervous depression”. Rest cures, developed during the nineteenth century as a treatment prescribed for “hysteria”, were most commonly levied upon women, due to the widespread belief that women were the ones primarily or exclusively stricken by the condition. Rest cures forbade activity of almost all kinds, both physical and intellectual – women were confined to bed for hours a day, months at a time, isolated from society and the company of friends and family, and forbidden to engage in anything that might be construed as “work”. Gilman wrote the story after experiencing a near breakdown herself, following a three-month rest cure prescribed by the pioneering physician of the treatment at the time. In “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper,” Gilman describes finally picking a pencil up after approaching the edge of her sanity: “I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the border line of utter mental ruin that I could see over. Then, using the remnants of my intelligence that remained…I cast the noted specialist’s advice to the winds and went to work again…ultimately recovering some measure of power.”

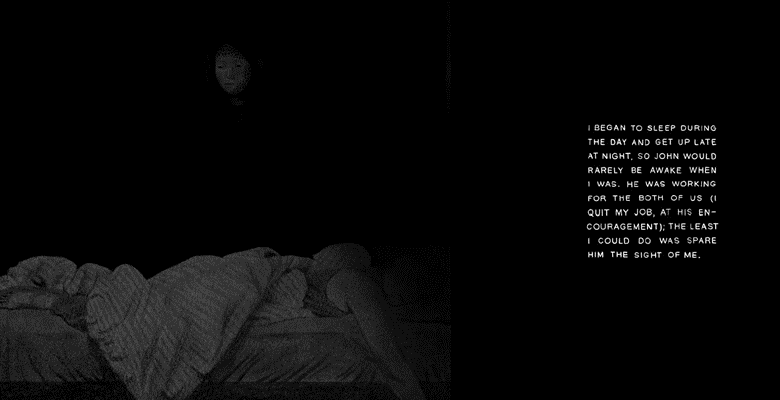

Gilman’s cautionary tale sees her protagonist cross that border which Gilman herself only toed, becoming fixated on the odious wallpaper from the title to the point of hallucination and a complete dissociation from reality. In the story, the prescribing Doctor – also named John, the namesake of Lannes’ titular antagonist – is the narrator’s husband, and thus holds a twofold power over her. “It is so hard to talk with John about my case,” she frets, “because he is so wise, and because he loves me so.” The darkness in The Yellow Wallpaper eventually takes form as the shadow of a second woman, trapped behind the paper arabesques. The narrator is ultimately subsumed by this projection, after freeing the doppelganger from the prison of the wall. Unable to acknowledge her husband’s condescending cruelty as other than the concerned ministration of a devoted spouse that it might outwardly appear, the narrator of The Yellow Wallpaper shares much with Lannes’ protagonist, who also harbors an absurd gratitude towards John even as he abets her self-destruction. “Dear John!” Gilman’s narrator exclaims, “He loves me very dearly, and hates to have me sick.” In a state of total self-abasement, Lannes’ protagonist reaches a point where she believes the best she can do for John is to at least spare him “the sight of me.”

While no medical prescription ties the central character in John, Dear to her bed, her isolation is just as profound as Gilman’s narrator. John moves in with her, pressures her to marry him, succeeds in encouraging her to quit her job, and fails to confront the worrying fact that she stops leaving the house at all. These all represent the same schisms encouraged by the rest cure in The Yellow Wallpaper, a break from employment, from society, from all of the meaningful activity of life. Lannes’ John performs care or concern like an actor anticipating his accolades, all the while nurturing the narrator’s depressed grief, self-doubt, and self-loathing. He tells her that he doesn’t care if she’s as quick or funny as she perceives him to be (preferring a vessel to an equal). Perhaps most tellingly, he claims not to have mentioned that she was developing holes on her face because he can still see her beauty and that’s all that matters. “You’re only really you in my eyes,” he croons. Like the Doctor-Husband in The Yellow Wallpaper, John believes he knows exactly who the narrator is, or at least should be. However, this pretension of intimacy is a calculated manipulation, designed to foster partners who are only allowed to define themselves in reference to him.

There are further illuminating parallels between the two works. Both women have their own understanding of their ailments dismissed by men who believe they know them better than these women know themselves. Both women are gaslit and denied validation when they express discomfort and trepidation about the course they’re taking. In John, Dear, the narrator’s physical affliction is eventually deemed unworthy of a doctor’s opinion by John, not serious or sufficiently important, the narrator tiredly agrees, to warrant “a massive hospital bill.” In The Yellow Wallpaper, when the protagonist expresses misgivings about the psychological impact of the wallpaper, John reverses his supposed initial inclination to re-paper the room. He chastises her, admonishing that “nothing [is] worse for a nervous patient than to give way to such fancies.” Both women are finally driven to adopt a nocturnal rhythm, retreating to the precious hours of time during which their partners sleep.

And finally, both women lose themselves entirely. Gilman’s character frees, and then becomes, the once-imprisoned woman behind the wall, shedding identification with herself in the process. Lannes’ narrator succumbs to the slow disintegration of her body and mind, until all that is left is the suggestion of her weight, or shadow, upon a mattress. This final chilling illustration echoes other comic images of the supine, sickened body monstrously transformed or abandoned, like in Junji Ito’s Long Dream. As with Gilman, you can’t help but assume that the disturbing verisimilitude in John, Dear is grown from the seed of personal experience. Both stories utilize their respective narrative forms to make the point that these kinds of abusive partnerships that are predicated on misogynistic paternalism, when unfettered, can literally destroy a person. What’s hopeful about these two women’s horror stories is that they exist as evidence of both survival and creative alchemy on the part of their resilient creators.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply