We’re all reasonably familiar with stories about the excesses of so-called “method” acting — Jared Leto being an unbearable jerk on the set of Suicide Squad because he refused to “break character” from his role as the villainous Joker, Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix living and partying for weeks on end with the young street hustlers they were portraying in Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (a situation which, depending on who you believe, may have been the genesis of the drug addiction problem that eventually cost Phoenix his life at a tragically young age) — and exploring where the actor ends and the role begins has been fertile ground for storytelling in various media throughout the years, perhaps the most notable recent example being David Lynch’s Inland Empire. Where Lynch posited (possibly) a kind of mass psychosis among the cast of his movie-within-a-movie (within, possibly, another movie — or radio drama, if you’ve seen it you know what I mean), Italian comics maestro Giorgio Carpinteri raises the stakes even higher with his latest graphic novel, Aquatlantic (Fantagraphics, 2020; translated by Jamie Richards), wherein an actor from Atlantis threatens not only the precarious socio-political balance of the fabled sunken city-state, but of the world itself, because he finds himself being consumed by the part he’s playing.

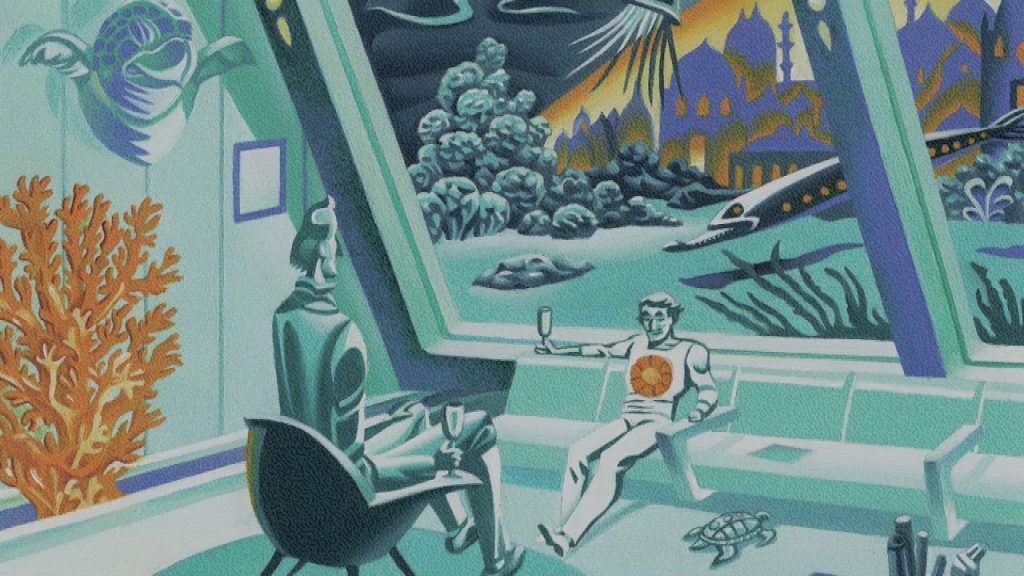

It may sound like a far-fetched premise, admittedly, to say nothing of a very ambitious one to attempt to tackle over the space of just 56 pages, but then everything about this book — presented in appealingly traditional Eurocomics “album” format — is over the top. Unless you consider talking (and, crucially, singing) turtles, recurring symbolic dreams, Dr. Strangelove-ian inept geopolitical intrigues, and worship of ancient undersea creatures to be everyday storytelling tropes, I suppose. And hey, this is the mile-a-minute imagination of Carpenteri we’re talking about, so such a view wouldn’t necessarily be out of place.

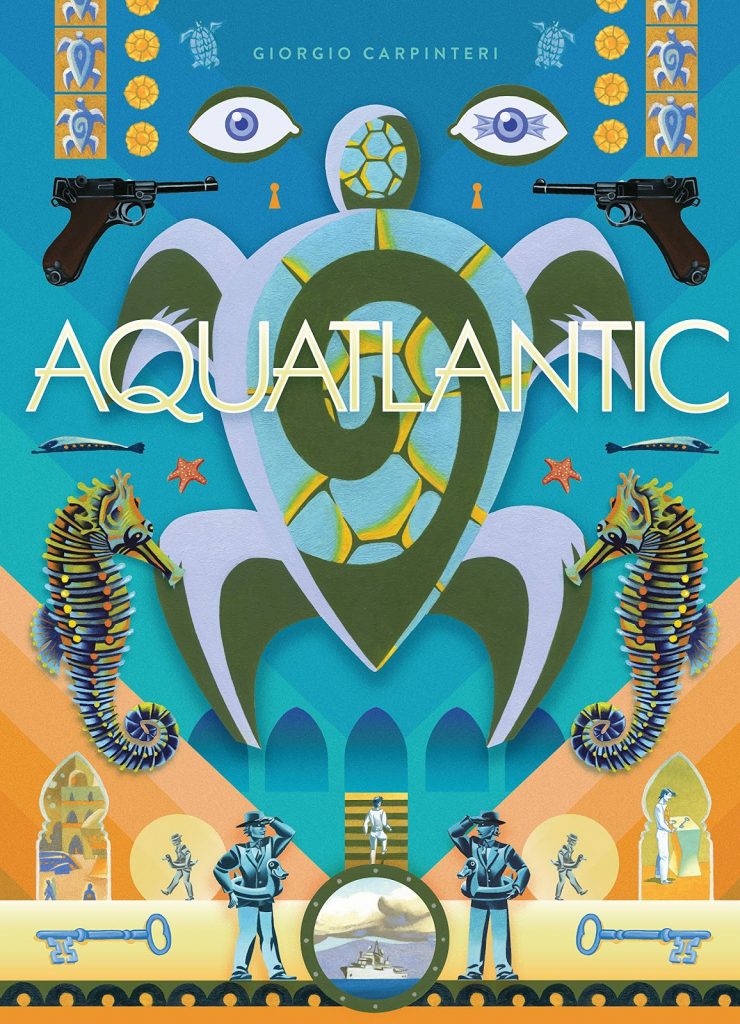

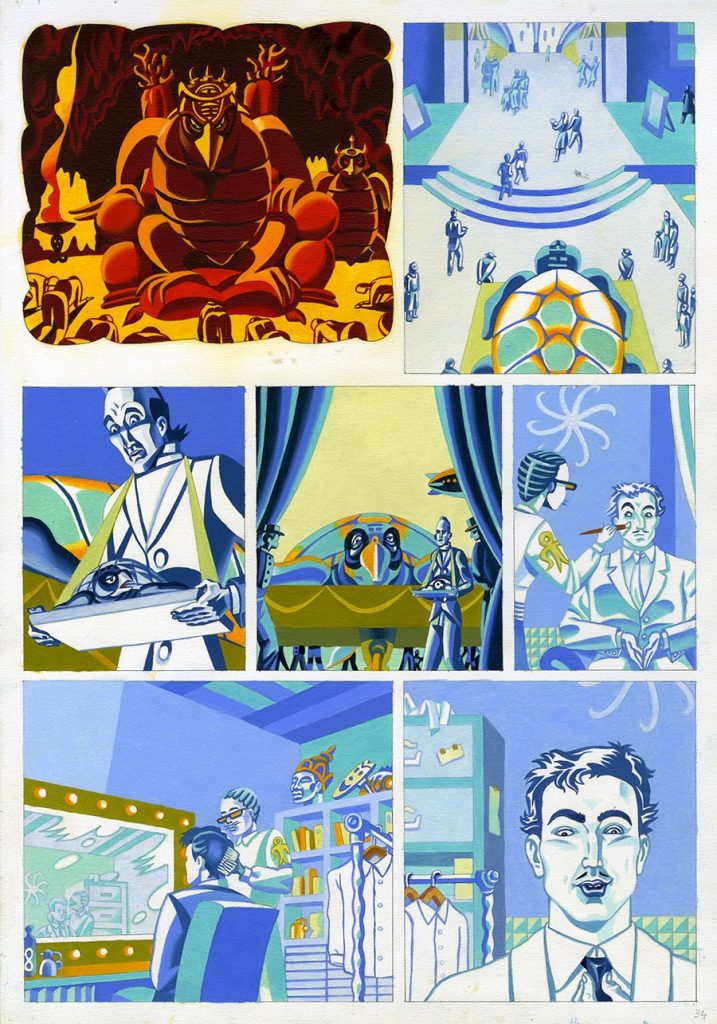

Still, it is a lot to pack in, and while you’ll be suitably wowed by Caprinteri’s stylish and colorful futurist art — part Cubist, part Art Deco, part Expressionist, part Constructivist, but always and entirely his own — on first pass, there’s a lot to process given the story’s rapid-fire clip and the numerous and narratively-necessary breadcrumb trails littered throughout it. Firm ground is a tough thing to find herein, then, but hey — we’re underwater anyway, so perhaps that’s only to be expected?

Fortunately, for a book that requires almost immediate and complete “buy-in” on the part of the reader to be successful, Carpinteri’s stunningly-rendered imagery offers you no choice but to — sorry — submerge yourself in at the deep end right from the start. Alien civilizations are never more alien and astonishing than when they’re right here at home — after all, in outer space, we expect this shit — and when communicated via means of a singular visual language that nevertheless incorporates instantly-recognizable stylistic elements, the right balance between foreign and familiar necessary to flesh out such a heady and dizzying array of oddities is achieved. Sheer sensory overload is never more than one concept or one illustration away from setting in, but Carpinteri’s been at this for decades now and knows just how many of his cards to show at any given time.

Summed up simply (okay, as simply as possible), what we have here is a world where Atlantis is real but is left alone by the surface-dwellers as long as they agree to never reveal themselves and accept their mythological status (a contrivance not entirely unlike that of the one explored by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely in Flex Mentallo, wherein super-heroes and villains from an alternate Earth escape the death of their own universe by becoming fictional characters in ours). As one would expect, then, Atlantean folklore and mythology are rife with tales of evil and unsavory folks who live above the waves, and it’s one of these personages, Ettore Patria, that first consumes a famed actor named Bho who’s playing him in a stage production, and then the status and power of Atlantis’ hypocritical ruling economic class. Throw in a lame-brained (by design, I assure you) plot by the powers-that-be up here on dry land to attack their undersea brethren, and the situation becomes a very combustible one indeed, and it really is all you can do just to keep up.

Fortunately, it’s not just Caprinteri’s admittedly astonishing art (as well as that of a few guest contributors, about whom I’ll say no more for fear of “spoiling” some fun surprises) that makes the act of keeping up such a joy. There is a welcome undercurrent (dammit, did I just do it with the aquatic references again?) of satirical humor, a rabble-rousing take on class warfare themes that never resorts to preachiness, a rather fascinating protagonist, and just enough eccentricity for its own sake to keep your mind as glued to the page as your eyes will be. It would be nice if Carpinteri had the space to explore some of these things in greater detail, no doubt about that, but he’s an established talent who calls his own shots, and if he’d wanted this to be longer, it would be. This is a solid enough examination of an imaginary world, then, but not a forensic one — and if you can deal with something that (don’t do it, don’t do it) dabbles its toes in own thematic waters but doesn’t necessarily plumb their depths, you’ll enjoy the experience.

That being said, even though there’s nothing about this work I’d call unsatisfying, much of it is abrupt — including the ending, which has a bit of a “reset button” feel to it. Caprinteri flirts with the idea of a massive societal shift in the end, only to opt for something rather close to a “whew! That was close!,” resolution, but to his credit, it does at least make sense within his book’s narrative framework, and he exposes plenty of hypocrisy and corruption among the elite ruling classes both above and below the surface to make his rather simple moralistic point perfectly clear. It’s an interesting choice to give such a breakneck and “high-concept” work such a tidy and traditional finish, but the dichotomy proves to be effective nevertheless.

Besides — if the biggest charge you can level against a book is that you wish it were longer, surely that proves that what you just read is some pretty good stuff? And the door seems to be left just a bit ajar for a potential sequel should Carpinteri decide to do one — which I certainly hope he’ll at least consider. I wouldn’t mind a deeper dive into the world of Aquatlantic in the least.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply