Publisher’s Note: Today we have the start of what we hope is an expanding conversation about the comics arts community and its goals, desires, and needs. Ken is a comics publisher who is exploring the ways in which nonprofit organizations (NPOs) can better assist the comics community. This first essay introduces the survey and an initial round of results. If you consider yourself a comics artist, please consider taking the survey yourself. Thanks!

Introduction

Who am I and what is this survey?

There is a good chance that you have no idea who I am. If you are a true devotee of small and micropress comics, you may be familiar with my Nix Comics publications, but honestly I don’t expect that. Even if you are familiar with my comics, though, you probably don’t realize that I’ve spent most of adult life working for small business startups and nonprofit organizations (NPOs for short). Most recently I worked as an administrator at an NPO that provided below market rate loans to affordable housing projects in the Columbus, Ohio area. I am currently enrolled at the John Glenn School of Public Policy to get a degree in Public Management with a nonprofit management minor. My broad goals are to use that degree, combined with my experience in administrative work at NPOs, to give back to the community of comic artists and fans.

As you know, not all knowledge or training is perfectly portable. My experience at the Affordable Housing Trust is valuable to setting up and maintaining a NPO, but much of that work was specific to the stakeholders in that realm: those needing housing and those providing it. Similarly, my Schooling at OSU can provide me with insight into how and why NPOs I have been associated with have or haven’t been successful, but it’s up to me to apply that insight to the needs and problems that face the comic arts community. Simply put, I need information about the stakeholders in the comic arts community. Unfortunately, stakeholder analysis of the comic arts field is a mostly new frontier with little published research, formal or informal. To apply my skill set to helping the comics community, I needed to explore and document that frontier myself. (Nobody said it was going to be easy!).

To that end, I am currently surveying comic artists to begin this complex work. My initial goals are to establish who comic artists are in terms of being community stakeholders and start a conversation about what the relationship between comic artists and NPOs should look like.

This is a fairly ambitious task, so I would be remiss if I didn’t take a moment to use my platform here to ask for help. If you consider “comic artist” as part of your identity, I would truly appreciate it if you could take my current survey:

https://forms.gle/FKnEFQAj88W3W87V7

If you want to know a little bit more about the survey first, as in what type of questions will be asked and what level of anonymity you can expect regarding your answers, please read on! In March, shortly before state isolation and social distrancing requirements were enacted, I conducted a test run of my survey with the vendors at the small Indie Comics Fair that I run annually in Columbus, Ohio.

Here is a link to the survey as presented to the vendors:https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NBKCxpOvpebSQZmKgp2hCBq5VSgKnvyR/view?usp=sharing

More about the Indie Comics Fair

First, in the interest of transparency, I should say that the Indie Comics Fair (ICF) is NOT a nonprofit event. I make a little bit of dough from it every year. It is, however, a very DIY event and I use many of the values I learned through work in the nonprofit sector in organizing the ICF. Artists bring their own tables. The fee for participation is flexible, with artists asked to pay “what it was worth” at the end of the day. The ICF is held at a nonconventional space (the Ace of Cups bar) in order to facilitate bridging the gap between the comic arts community and the wider Columbus community.

The Fair is co-sponsored financially by Bob Corby of the Small Press and Alternative Comics Expo (SPACE). The funds Bob kicks in go towards paying an artist for a poster and on-line advertising of the event. This year’s poster, above, was created by Renkorama and the chalk cartoon on the sandwich board by Timmy Wade.

Notes on Survey Response and Methodology:

A printed version of the survey was given to vendors at the beginning of the show with instructions to return the completed survey to me by the end of the Fair. 22 of 24 total vendors were given the survey. I did not take my own survey and did not administer it to one vendor who was a retailer, but not an artist themself. 14 of those 22 responded to the survey. I honestly was not sure how open the vendors were going to be to this survey. They were not told in advance that I would be conducting it and, despite promises of anonymity, it does ask questions that justifiably could raise red flags for those concerned with privacy. As I continue my research, I will feel fortunate if my outreach efforts continue to have an engagement rate of around 63%

The responses on the survey can not be applied to the comic artist population as a whole, as the sample size is too small and is subject to the biases inherent to the methods of vendor registration. Firstly, I view diversity as a strength and as an asset, so I always make an invitation list of artists I would like to be represented before opening up registration to everyone. Frankly, my general experience is that if I don’t take that step then the venue will fill up with the same middle aged white guys within a day of posting the application link. This year, the advance invitation list included nine Columbus College of Art & Design (CCAD) Comic Major seniors and therefore, some questions, such as sources of income and length of career, are biased towards their experience.

Part One: Establishing Comic Artist Identity

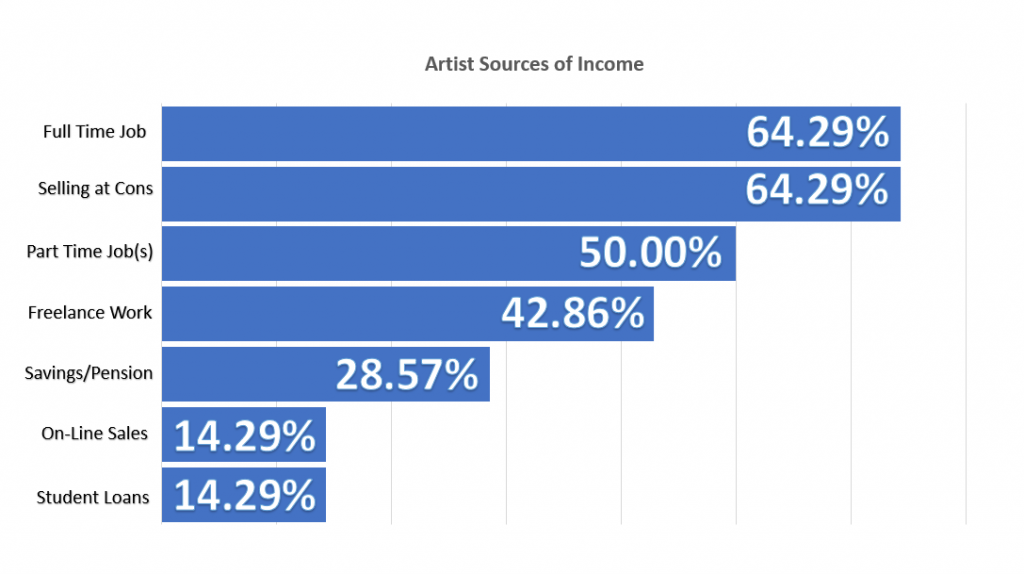

Sources of Income

Many NPOs base their mission, social contract, and guiding philosophy of change on the premise that they exist to address market and government failures to properly distribute goods and resources. These NPOs tend towards providing services and goods that impact the non-competitive nature of the comic arts market. Others view their work as NPOS asbeing independent of the market and government sectors; instead, they view their role as guardians of common goods and values. These NPOs tend towards initiatives that address the lack of information and appreciation for the comic arts field in general. While NPOs with non-market failure philosophies don’t necessarily have an obvious stake in the needs of artists as stakeholders, they do have a stake in the continuation of the artform and the establishment of a condition of affluence among comic artists sufficient to continue their work. This makes it necessary to establish artist identity in terms of employment and access to resources.

The respondents to this survey showed a high degree of financial stability. 13 out 14 of the survey respondents reported either having a full-time or part-time job. One vendor reported having both a full-time and at least one part-time job. Additionally, respondents showed a high degree of diversity of income sources: 13 out of 14 respondents reported having multiple sources of income with a median of 3 sources of income per vendor.

In terms of defining comic artists stakeholders, the results showed that there are distinctly two types of artists, those who work as full-time artists and those who work as artists part-time. The survey results do tell whether the latter stakeholder is part-time by choice or because financial and social constraints dictate part-time status. It is notable that in the subsequent question regarding the number of hours spent on comics work, only one respondent reported a range of hours per work that would be considered part time.

It is also notable that five respondents didn’t list any of the following as a source of income: freelance work, on-line sales, or cons as sources of income. This is interesting from the perspective that they were literally at an event selling comics! That suggests that they don’t consider comics a source of income at all. This may be literal, in the sense that they spend more than they earn making comics, or it may be philosophical in that any money earned is secondary to the utility that they gain from creating and sharing comic art, free of professional aspirations. These respondents require a third stakeholder category outside that of full or part-time artists. While recognizing that the term can be used as a diminutive, the term “hobbyist” best describes these artists who create for purely personal edification or pleasure.

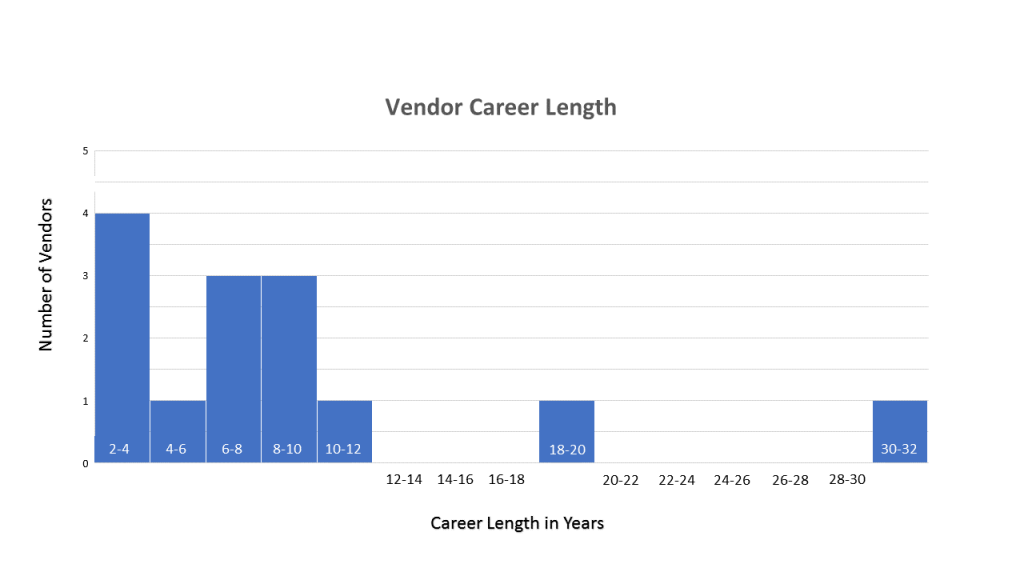

When Did Your Comics Career Begin?

This question was left intentionally vague, with the artists themselves defining what determines the start of a career. They could define it as their first published or self-published comic, first sold piece of art, or even the start of schooling in the case of the CCAD students surveyed. It could even simply be the day that the artist decided to be an artist. Deeper research would likely reveal that what constitutes the definition of a comic arts career varies widely from artist to artist. For the purposes of this survey, though, the definition was left open ended to prevent my personal bias on the subject from influencing the respondents’ answers.

Survey respondents reported career start years that ranged from 2017 to 1988, with an average career length of 9.5 years and a median of 8 years based on those responses. The vendor with the 32 year career was a statistical outlier, pulling the average up despite the bias towards lower career lengths created by the large number of vendors who were students. While the results of this survey can’t necessarily be applied to the comic arts community as a whole, the results of this question indicate that between 8 and 10 years ago there was an increase in the number of comic artists in the Columbus, Ohio area. The reasons for this increase are likely many and would make an interesting point of further study.

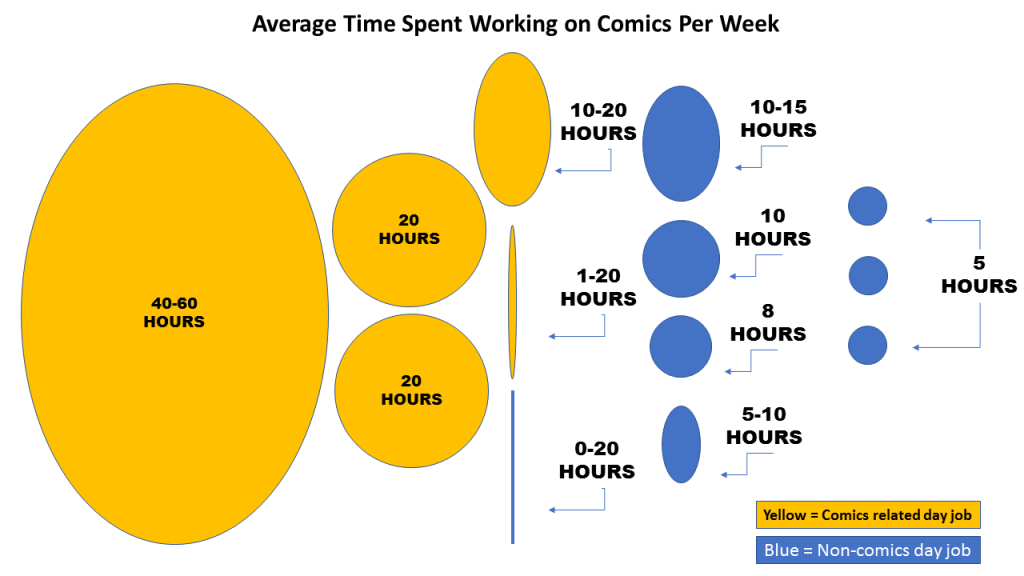

How many hours a week do you work on comic art?

This question was presented without designated buckets (designated increments, for example 1-5 hours, 6-10 hours, etc.) in an effort to gain insight into how wide the spectrum of hours that respondents devoted to comic arts work. Answers to this question showed a significant degree of variation: 5(x3), 8, 10, 20 (x2), 5-10, 10-15, 10-20, 1-20, 0-20, 40-60, and an unspecified “varies.” When this information is presented as shapes with dimensions defined by the range of hours reported, it shows how significant the difference can be between artists and their ability to sit down at the drawing board/writing tablet.

Is Your Day Job Arts Related?

This question was presented to respondents to test the hypothesis that comic artists whose source of income and day to day work are art-related have better access to resources and an advantage in the ability to create comics. Five respondents listed their day job as comic arts related. All five of these respondents reported spending more time creating comic arts than other vendors. Again, this finding is reflective of the biases in vendor selection, with both CCAD students and instructors in the mix, but it is a notably stark difference. This is another area where further study would be important.

Do you see a clear path to achieving your artistic aspirations?

Like the question on comic career start dates, this question was left intentionally loose, the importance being to not impose my biases as a researcher on a subjective (yet important) issue. 10 of the 14 (71.43%) respondents said that they saw a clear path to achieving their artistic aspirations. This sample also most likely had a high percentage answering affirmatively due to the biases created by vendor selection. The CCAD instructors do an excellent job preparing their students for comic careers, so the CCAD students are likely optimistic. The stakeholders identified as hobbyists by the sources of income question are likely achieving their aspirations simply by being at the show. What this question doesn’t answer, however, is the degree of difficulty artists see in achieving their goals despite that clarity of vision.

In the second part of this survey, artists reported desiring a median number of five different types of services from NPOs, indicating a perception that there are a multitude of barriers to success.

Do you identify as a member of a community that is frequently and/or historically the victim of discrimination and bias?

There is a deep rooted perception that comic arts is a potential safe space for marginalized groups, as well as pushback on that concept by conservative flank elements in the community, making this question important to questions of comic artist stakeholder identity. This question was framed as a simple yes/no answer to emphasize the importance of addressing that need. 10 out of 14 respondents (71.43%) identified as being members of a group that experiences bias and discrimination, indicating that this sample group of artists have a social context external to the comic arts community that impacts their stakeholder identity.

The yes/no format of this question is not to say that issues of broader cultural bias are simple matters to be addressed with a broad brush. Rather, it is quite the opposite, studying marginalized and disenfranchised groups is a complex matter that requires research that could not be addressed effectively within the context of this survey.

Part Two: Nonprofit Organizations, The Community, and You

Establishing the identities of comic artists is, of course, only the first part of problem-solving on their behalf. The second section of the survey is designed to assess comic artists’ perceptions of their own needs. This is a key element for effective stakeholder analysis, public management, and nonprofit mission/program building.

As a side note, I was initially advised to rinse these questions of the academic tone and terminology in order to make the survey more accessible to the respondents. I ended up not taking that advice for two reasons. The first being that I trust the comic arts creators to be intelligent and capable readers. It’s one of the hallmarks of the community. The second is that I believe in empowerment. The language of the second part of the survey relates directly to the way in which NPOs are managed and funded. By supplying artists with that language, it reduces barriers to participation and dialog with the entities empowered to help them. Nothing makes a nonprofit manager’s ears perk up quite like terms directly related to their budget!

What types of activities would you like to see NPOs take part in to address the problems facing comic artists?

It would be unfair to imply that NPOs are created spontaneously in a void and their mission statements plucked from the ethereal plane. Comic Arts NPO work is largely conducted by earnest members of the comic arts community who see problems and seek to address them. It is, however, fair to question the accuracy of their problem framing and need for the programs provided to solve those problems. Artists are often forgotten as a resource for program development in the very programs meant to aid them.

The first five options for program services provided in the survey came from the perspective of NPOs existing to correct market failures. The primary aspects of a perfectly competitive market are 1) a large number of buyers and sellers, 2) no barriers to entering or leaving the marketplace, i.e. there are no transaction fees for participating in the market, 3) Buyers and sellers all have complete knowledge of the goods being sold, and 4) goods are standard in format and pricing. A perfectly competitive marketplace, of course, does not exist in any field. Markets are on a spectrum of more and less competitive. The less competitive a marketplace is, the more inefficiently goods and services are distributed. These failures in distribution are the definition of market failure.

It is fair to say that respondents to this survey see market failure as an issue for their work. Ten categories of services typical of NPO programs and missions were presented to survey takers. Surveyees were asked to select all services that they were interested in receiving. Three of the top five services (mitigating participation fees, informing buyers about work, increasing the number of buyers) selected by respondents deal directly with elements of a competitive marketplace. Also in the top five was a desire for training in the business of comics, which is a not a service that would seek to address market failure, but would aid artists in navigating the non-competitive comic arts market.

The ten services presented to survey takers were divided into two categories: NPO services that specifically dealt with market failure and NPO services that function external to the market. While the latter category has bearing on the health of the comics industry, the services offered view comic arts as a common good to be developed and maintained independent of the marketplace for the benefit of society in general.

It is important to recognize that there can be overlap between the first and second groups of services. For example, a fundraiser that commissions artists for work to be sold in benefit of artists with health needs would create work for artists at the same time it performed a non-market service.

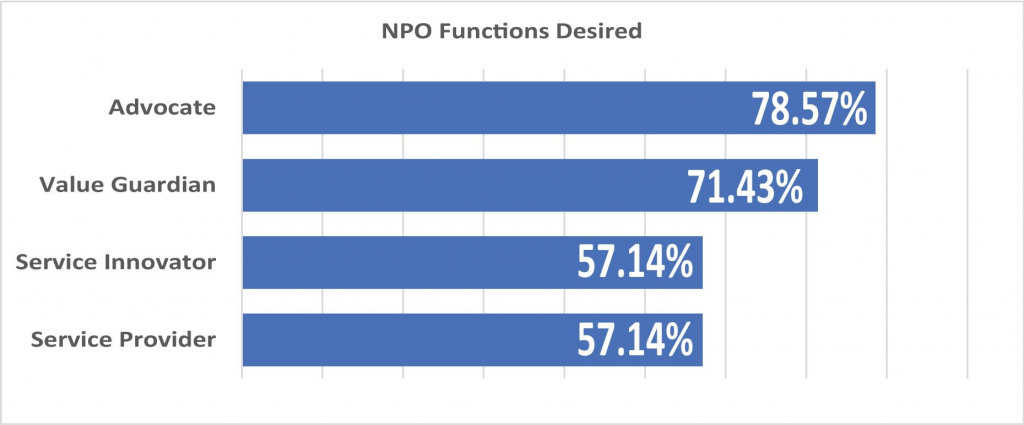

What functions do you wish to see comic arts NPOs performing to address problems facing the comic arts community?

Just as there is diversity and complexity within the stakeholder identity of comic artists, NPOs are stakeholders with degrees of differentiation in terms of the function they serve. Using these functions to categorize NPOs as stakeholders, the survey takers were asked to select the types of NPOs they would like to see active in the community. .

Services and Resources: The NPO provides services and goods that mirror for-profit services and goods, but use the advantages of nonprofit status to achieve positive outcomes for artists.

Innovation: The NPO provides services that are substantively different from similar for-profit services to achieve positive outcomes for artists, such as research into possible alternative market models for the comic arts.

Value Guardian: The NPO champions the creation and consumption of the comic arts to the general public to create greater understanding and deeper interest.

Advocacy: The NPO speaks to power on behalf of comic artists, including but not limited to the government, courts, publishers, retailers, distributors, and other NPOs.

These basic NPO stakeholder categories are not firm or mutually exclusive, with some NPOs serving multiple functions. Respondents in general saw a need for all four categories of NPO, with none of the four getting less than 57% of the vote. This again points to artists seeing a path to their artistic aspirations, but not necessarily an unencumbered path. Interestingly, respondents preferred the idea of NPOs serving as Advocates and Value Guardians by a fairly wide margin over Service Providers and Innovators. This stands in tension with the overall preference for programs that address market failures because Service Providers and Service Innovators directly address market failure. On the other hand, Value Guardians and Advocates act externally of the marketplace. Value Guardians rely on changes to culture as a whole to create an environment where the market will presumably correct itself. Advocates speak to power on behalf of artists, which has an implicit assumption that the marketplace is healthy enough to support the artists they are advocating for with changes to existing factors of competitiveness.

What values would you expect to guide a comic arts NPO?

My good friend Ella once told me that “it ‘taint what you do, it’s the way that you do it.” Therein lies the true complexity of running a NPO. While for-profit organizations are governed primarily by owners and boards with a single bottom line of profitability, NPOs are subject to community governance. Other stakeholders have expectations of not only outcomes, but also the manner in which those outcomes are achieved. These expectations can be particularly hard to juggle, especially when stakeholder expectations are in conflict. Board members, sponsors, artists, fans, and other stakeholder categories may not agree on what values the NPO should act upon, particularly in the case of NPOs acting on values preferred by sponsors over those of beneficiaries of the NPOs’ services.

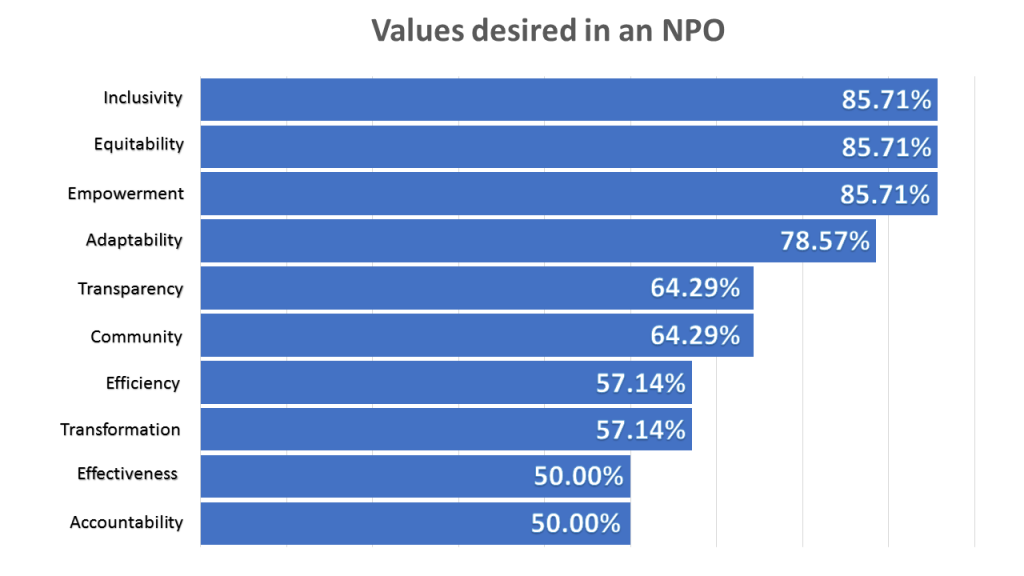

The respondents were given this list of values and asked to select all that they wished to see guide any NPO in their community:

Efficiency: The NPO seeks to get the most possible out of its available resources (financial and otherwise). The NPO is a good steward of funds: sponsor donations and participating artist service fees alike.

Effectiveness: The NPO seeks to create the most or best positive outcomes for artists and guards against negative spillover effects their programs may generate.

Inclusivity: The NPO embraces the gifts of diversity and actively reaches out to and meaningfully engages with artists of socially diverse backgrounds.

Equitability: The NPO acknowledges the historical and current roles of wealth, race, and power in the comic arts field. The NPO takes steps to ensure that the needs of artists are not crowded‐out by more powerful stakeholders or unfair social norms.

Accountability: The NPO is dedicated to self‐evaluation and reporting. The NPO is responsive to artist and other stakeholder’s efforts to engage, including dissent and protest.

Transparency: The NPO performs its duties in a manner that is easily traceable and identifiable to artists and other stakeholders. The NPO is open to further public requests for information.

Adaptability: The NPO is structured so as to be able to adjust its programs, its initiatives, and even its mission based on input from the community it supports. The NPO is willing to self‐correct in the face of its own errors and social change.

Empowerment: The NPO seeks to make long-term improvements in the lives, careers, and social status of comic artists.

Community: The NPO seeks to build relationships between all members of the comic arts community, creating bridges between its stakeholders such as artists, readers, publishers, retailers, and the NPO’s board itself.

Transformation: The NPO is dedicated to innovation and societal change in support of its constituent artists. The NPO supports and fosters activism.

The desired values rated most highly (Inclusivity, Equitability, Empowerment, and Adaptability) align well with the results of the previous question regarding artistic aspirations This shows that the most desired function of an NPO is advocacy. The artists responding to the survey see the comics community as an inviting community to be a part of, but, as stakeholders, they want NPOs to maintain and develop the artist’s stake in the community. Artists desire a voice and a hand in the direction that their community takes.

More Dialog, Please!

I’ve already confessed to the bias inherent to this study. Assertions about the comic artist community and its reputation as a whole require far more study and more conversation. To that end, I really want to hear from more artists so that I can create a valid and valuable resource for community action. I want to hear all feedback on this survey as an instrument, as well as any speculation inspired by its results. Do the results match your expectations? Which areas of the survey would you like to see further research into? What do you think the results of a larger poll would look like? Hit me with it!

Oh… hey… speaking of “hitting me with it,” let me reiterate that I am conducting a survey on-line right now! If you consider yourself a comic artist, I would be very grateful if you could take the survey. It takes most people 5-10 minutes to complete. All results will be presented in the same manner as this report to preserve anonymity.

Survey Link: https://forms.gle/FKnEFQAj88W3W87V7

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply