TLDR… ER… I MEAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

I have a hypothesis that at comic shows, Special Guests can negatively impact the sales for paying vendors. This is because the factors of a competitive market are not the same between the two stakeholders and because the budget of customers is limited. Paying vendors experience a market failure due to an information asymmetry: customers know more about the Special Guests (duh) and are therefore more likely to spend their money on those guests. The result is that while a guest list is the primary tool comic shows use to attract customers, adding Special Guests will have a negative spillover effect on the total spent on paying vendors. This effect can be modeled and the hypothesis tested with a social experiment involving running two similar comic shows. One with Special Guests and one without, but otherwise the same. Conducting this type of research would provide a valuable tool for artists and the comic shows themselves.

THE HYPOTHESIS:

So, I have this hypothesis about financial success at comic and cartoon festivals, fairs, and conventions. That hypothesis is that as the ratio of Special Guests on the market floor at any comic show increases as compared to paying vendors, the overall sales for paying vendors goes down due to the inherent information disparity between the two stakeholder types.

Stakeholder Identity designations for the purpose of this essay:

ARTISTS: Creators vending in comic show marketplaces, including both Special Guests and paying vendors.

SPECIAL GUESTS: Artists who have been compensated for their appearance at the comic show and are vending or selling in the marketplace. Compensation can include actual pay, as well as perks such as free tables, preferential placement on the market floor, prominence in advertising/marketing materials, etc.

PAYING VENDORS: Artists who pay for their space on the market floor and no additional perks.

COMIC SHOW: Comic festivals, fairs, and conventions that offer a transient marketplace as part of programming.

CUSTOMER: Any person buying from artists at the comic show.

Basically, customers at shows are going to tend to spend money on the artists with whom they are already familiar. Since customers have a limited budget, as Special Guests are added, overall sales to paying vendors will decrease. It’s a market failure due to an information disparity. This creates tension for comic shows because they measure success by the number of customers through the door and Special Guests are a tried and true method of generating that foot traffic. As the size and quality of their guest list increases, the number of customers also generally increases. Graphed the effect would look something like this:

Oh… Wait… This a graph showing how long I can keep a grudge against the people who have dismissed this hypothesis out of hand. Some of them are artistic peers. Others are people who actually run shows. Often the rebuke comes mockingly, since the hypothesis runs against the conventional wisdom that “more feet through the door is better for the Comic Show and is, therefore, better for everyone involved.” Sometimes the dismissive explanation even runs to the extent of suggesting that many comic artists vend at comic shows for reasons other than selling their comics. The former is bad economics. The latter is dangerously close to exploitive, implying that because Comic Artists gain non-monetary satisfaction from vending at shows that those charging fees shouldn’t show some fiduciary duty to those artists and use of their table fees (Caveat emptor, indeed…).

I won’t lie. The dismissiveness is particularly galling in that it dismisses my personal experience. Like a lot of artists, I keep track of these things! Special Guest oriented shows have higher table fees. As table fees increase, my total sales go down in proportion to those table fees. For example, if I pay $50 for a table I can usually make $100 in sales. A 2 to 1 ratio. At $300 table fee show I usually make that $300 back in sales, or a 1 to 1 ratio. That’s my typical experience. When I encounter people who insist that larger shows equal larger sales it’s like they’re asking me whether I’m going to believe their rule of thumb over my lying eyes. Hence the grudge.

You know what, though? I don’t want to hold a grudge against people I actually generally like, many of whom earnestly want to improve the Comic Arts community, including the fiscal health of artists. So here’s the deal. I’m going to use this space to share my personal experience on the matter, share a little bit about what can be gleaned from a small artist survey I conducted last year, model why I think that ratios of Special Guest to paying vendors can cause problems for the paying vendors, offer a method for proving that model, and then provide some suggestions to different stakeholder groups for addressing the problem.

MY EXPERIENCE:

Below is a chart that shows the Nix Comics average sales at comic shows categorized by the price range of the table fee expressed as a ratio to the actual table fee. For me, the sweet spot is that first tier in green, which is mostly populated by small “indie-oriented” shows with table fees less than $100. At these type shows, I can generally make back two and a half times the amount I spend for my spot in the marketplace. As the average cost of tables goes up by increments of $100, my average ratio of sales compared to that higher fee goes down.

There is of course a lot of variance from show to show and averages and ratios can distort the reality. The scatter table below will give you a better idea of what Nix Comics’ performance has looked like at shows where I have paid to be a vendor.

In this format, it is possible to rate relative success for paying for a table. The red line reflects the point at which I would make my table fees back in sales, my bare minimum benchmark for success. The green line notes the point at which I at least double my table fee and is usually indicative of making some level of profit inclusive of printing and travel costs.

You can see how at the $300 table mark, which includes shows such as New York Comic Con, SPX, and MOCCAfest, I rarely hit over the red line and have never scored into the green. A commonality between these shows is extensive guest lists and generally higher traffic. Essentially the only reason for me to attend these shows is social: building community, personal entertainment, and professional edification.

For shows under $100, my results generally hover around the green line, except for that one sad day I paid $25 for a table and made no sales. These shows include small press centered comic shows like Small Press and Alternative Comics Expo (SPACE) and Cleveland’s Genghis Con. These shows are vital to me in that they provide a fairly reliable source of income as well as the social aspects.

In the middle ground both in table rates and sales rates are shows costing over $100 but less than $200. These shows include local “comic conventions” that follow the San Diego style on a smaller scale and some of the larger alternative press friendly shows like Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC). In both cases, the guest lists tend to be fairly extensive. These shows are a bit of a crapshoot and can’t be looked at as a consistent or reliable source of income.

I’m not sure if it’s just my experience that there is a dearth of shows in the $200 to $300 range for table fees or if there is an actual jump in the market for some economic reason (like once you hit a certain size, expenses start compounding).

Have You Considered That Maybe You Just Suck, Ken?

Believe you me, the thought that it’s “just me” and that maybe my appeal plateaus at a certain level has occurred to me. I’m positively awash in confidence that I’m a weirdo loner with a niche product. That’s why I do the survey work among artists, including a survey specific to artists who counted comic shows as part of their income in my 2020 Comic Artist Survey.

While this survey didn’t go into the granular details of economic success at comic shows, it is notable that all respondents stated that table fees were at least somewhat of a barrier to attending shows. Only 19% of respondents reported regularly making back all of their expenses of vending at Comic Shows, and many of the respondents in the open answer “additional information” question indicated that they had selective success based on the size and type of Comic Show or concessions made to the format, such as table sharing.

While this survey had a pretty low sample size (33) and is subject to selection bias, the results do tell me that there is something at play in the community for at least a portion of the comic artist community. In short: “Hey man, It’s not just me… it’s me and my friends…

Modeling The Special Guest Effect:

It’s going to get a little “Microeconomics 101” here. Forgive me. I’m going to do my best to explain my ideas to you in the way I wish my economics professors presented the concepts to me.

The first thing I think it’s important to model is that conventional wisdom; “A Special Guest list brings in more customers, which is good for all of the vendors” is simply not as solid an axiom as it would seem. It implies that adding Special Guests would create a graph like the one below where, as Special Guests are added, sales go up. Special Guests are an “input” for production. “Production” is measured by either the number of customers or the amount of money spent in the marketplace.

There are two problems with modeling the effects of Special Guests in this way. The first is that it ignores the law of diminishing returns. The second is that it assumes what is good for the economy of the Comic Show is good for all vendors.

In terms of the economics of running a show and Special Guests, the law of diminishing returns manifests as an equilibrium on a bell curve point. A sweet spot to find. It’s like this: as inputs in the form of Special Guests are added, the show gets some degree of increase in the number of customers. However, shows also have an increase in expenses with each new Special Guest. The difference between the benefit and the cost is the “marginal return.” The thing about marginal return is that it isn’t always an upward sloping straight line. There inevitably comes a point where the expense of adding a Special Guest actually negatively impacts the show’s overall marginal return (i.e. they spend more money on appearance fees, advertising, and such than they make on any new Special Guests). It’s the job of the people running a comic show to find this sweet spot for a successful, healthy, and ongoing event.

But… But… I think there is a not-so-great assumption that the success and health of an ongoing event carries over to consistently positive results for sellers within the marketplace. “Good show. Lots of people show up. Everybody is happy.” While I’ll concede that this would be true in a competitive marketplace where all participants are subject to the same factors of competition in the marketplace, the division between Special Guest and paying vendor makes that not the case. For instance, not all sellers face the same transaction fees for entering the marketplace since some are paying a table fee and others are being compensated for their appearance. Along those lines, Special Guests are able to negotiate that compensation, and, so, are not “price takers” in the marketplace. The largest divide in terms of a competitive marketplace comes in the form of an information disparity. Special Guests are picked specifically for their relative level of fame and respect. This initial advantage is compounded by the comic shows needing to maximize their investment in the Special Guest through advertising and marketing, expanding the existing information gap. The end result is that paying vendors find themselves on a very different curve in terms of the marginal returns and equilibrium points in regards to added Special Guests.

An easy conclusion to jump to would be that the paying vendors are simply not all benefiting to the same degree from the new feet through the door brought by the Special Guests. Through the merit of their work, the Special Guests are deserving of a greater share of the whole. This assumes, though, that the effect of Special Guests on paying vendors is not merely additive. Since the market discrepancy is primarily one of information disparity combined with the limited funds of the customers, we know that there is a negative spillover effect for paying vendors with each new Special Guest. Customers will adjust their spending towards the new vendors that they have more information about.

Indulge me a little here. Say that when I set up my next Indie Comics Fair in Columbus I have a small group of Special Guests that I am paying to attend and the remainder of the vendors are paying vendors. This set up yields me the following group of customers who will spend their money between the two groups as follows:

| Buyers | Amount spent on Special Guests | Amount Spent on Vendors |

| Johnny R. | $50 | $0 |

| Joey | $20 | $30 |

| Dee Dee | $35 | $15 |

| Tommy | $25 | $25 |

| Marky | $35 | $15 |

| Richie | $35 | $15 |

| Clem | $10 | $40 |

| C.J. | $20 | $30 |

| Belinda | $15 | $35 |

| Jane | $0 | $50 |

| Charlotte | $25 | $25 |

| Kathy | $30 | $20 |

| Gina | $25 | $25 |

| Mick | $25 | $25 |

| Dan | $25 | $25 |

| Peggy | $25 | $25 |

| Total | $400 | $400 |

| Average | $25 | $25 |

Yes. That’s right. All of the Ramones, Go Gos, and Gories are coming to buy comics at my Indie Comics Fair. I’m that cool.

…Anyways.

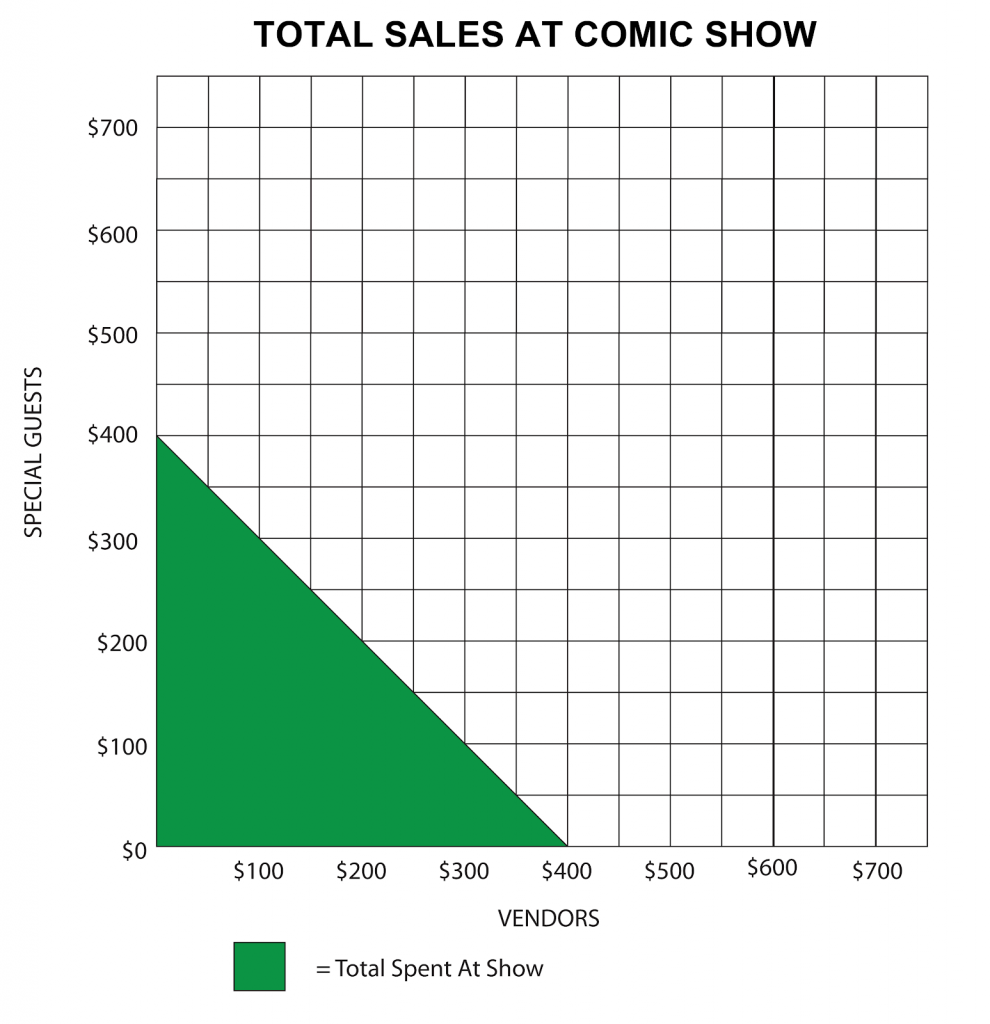

Those sales could then be graphed as below, with the total for Special Guests as a starting point on the Y-axis and the total for paying vendors on the X and drawing a line connecting the two. The area underneath represents the total sales at the Indie Comics Fair.

So what happens when I add a Special Guest? The new guest attracts the Talking Heads and the Slits. They spend their money at the show as follows:

| Buyers | Amount spent on Special Guests | Amount Spent on Vendors |

| David | $50 | $0 |

| Tina | $25 | $15 |

| Chris | $25 | $25 |

| Jerry | $40 | $10 |

| Viv | $35 | $15 |

| Ari | $30 | $20 |

| Olive | $45 | $5 |

| Tessa | $25 | $25 |

| Total | $275 | $115 |

| Average | $34 | $14 |

This has the effect of increasing the overall sales at the Indie Comics Fair. The line connecting the two axes shifts right and the size of the shaded area grows. As a whole, the show is more successful.

That’s good, generally speaking… But there’s also that negative spillover effect from Information disparity to take into account. While punk rock bands aren’t monolithic in their tastes and influences, they are often similar. You can expect that some of the Ramones, Go Gos, and Gories are going to change their spending behavior. More money will go to the Special Guest that they might already have a relationship with or have more information about. The changes, in this case, would look like this:

| Buyer | Amt. Spent on Special Guests | Amt. Spent on Paying Vendors |

| Johnny R. | $50 | $0 |

| Joey | $45 | $5 |

| Dee Dee | $35 | $15 |

| Tommy | $50 | $0 |

| Marky | $35 | $15 |

| Richie | $35 | $15 |

| Clem | $10 | $40 |

| C.J. | $45 | $5 |

| Belinda | $15 | $35 |

| Jane | $0 | $50 |

| Charlotte | $25 | $25 |

| Kathy | $30 | $20 |

| Gina | $40 | $10 |

| Mick | $50 | $0 |

| Dan | $35 | $15 |

| Peggy | $25 | $25 |

| New Total | $525 | $275 |

| New Average | $66 | $17 |

When you graph the new totals on the X and Y axes, the total has changed, as well as the slope of the connecting line. This new rotated line creates a different shape that, when laid over the original graph, illustrates the total money lost by paying vendors to Special Guests.

It’s cool though, because it’s likely that part of their higher table fees went to compensating the Special Gue… HEY WAITAMINUTE. THAT AIN’T COOL!!!

Nice graphs dude, but can you prove any of this?

You’ve maybe noticed that I have been careful to phrase this issue in terms of effect, i.e. the effect that Special Guests have on paying vendors. That’s because among the people I’ve held grudges with over this hypothesis there is a common refrain of “you can’t know this happens because you can’t prove a negative.” The idea behind that is that I can’t directly tie a dollar spent on one artist to a loss of a dollar to another artist in the same marketplace. That’s probably right. I can, however, prove a situation where one group of stakeholders has a negative effect on another group as a whole. Experiment time!

I propose an experiment where two separate comic shows are conducted for the purpose of collecting information. The two shows will be run the same way (location, hours, advertising budget, types of marketing materials, similar programming) except that one show will feature only paying vendors and the other show will feature a slate of Special Guests with changes in expense of running the show and change of focus in marketing materials.

So, basically, two treatment groups: Group A (paying vendors only show) and Group B (paying vendors with Special Guests show). Total sales from each paying vendor will be reported in a post-show survey. Additional information (such as types of items sold, vendor demographics, location on the market floor, type of signage, etc.) can be collected in this survey to make a more granular examination possible, although the main goal will be comparing a sales-to-table fee ratio between the two shows.

As “paying vendors” would be part of an experiment, it would be ethical to provide a payment or honorarium for their participation as opposed to charging them a fee to participate. A “table fee” for each show would need to be calculated based on expenses and the total number of paying vendors. Below is a pro-forma budget for a show based on my past experience running and participating in comic shows, including a calculation for what the likely table fee would be in a for-profit situation.

| Expense | Show A | Show B |

| Venue (rent, Insurance, utilities, et. al.) | $1,250 | $1,250 |

| Marketing (Graphics + Art budget) | $250 | $250 |

| Marketing: Digital (Website, social media ads) | $250 | $250 |

| Marketing: Print (Posters, flyers, handbills) | $50 | $50 |

| Staffing: Show Management (30 hours work at $20/hour. Not including Special Guest Specific Tasks) | $600 | $600 |

| Staffing: Special Guest Management (1 hour/Guest at $20/Hour) | $0 | $100 |

| Staffing: 2 Show day assistants, 12 hours each @ $15/Hour | $360 | $360 |

| Staffing: Pre-Show Handbill distributors, 2 at 4 hours each @ $15/hour | $120 | $120 |

| Artists: Special Guest Fees/Expenses | $0 | $2500 |

| Artists: Show Amenities ($5 per artist) | $150 | $175 |

| Total | $2,940 | $5,590 |

| Paying Vendors | 30 | 30 |

| Special Guests | 0 | 5 |

| Cost Per Paying Vendor (“Table Fee”) | $98 | $186 |

Keep in mind “pro-forma” is a fancy way to say “spitball.” An actual budget based on actual quotes would need to be put in place.

Venue: Based on past experience, previous event quotes, and a quick check of a site featuring some listed rates for local venues.

Marketing: There are few set rates in the world of marketing and no limits on what you CAN spend if you want. These numbers are based on my own experience with finding an equilibrium between spending on marketing and return on investment. Special note: As creating art for a show is a form of recognition and comes with compensation, artists paid to create graphics for a show should not be eligible to be a paying vendor, although Special Guests should be eligible.

Staffing: The $20 per hour for show management is based on the $24.33 per hour average reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, bumped down for the bias towards lesser pay for nonprofit work. The number of hours is a low estimate. The $15 per hour for show assistants and help handing out handbills is based on my own expectations of what a minimum wage should be.

Artists: The Special Guests total assumes an average of $500 per guest. This is inclusive of lodging and travel if required. This total will likely preclude higher profile Special Guests. The amenities include providing water, light food service, a first aid kit, and any needs for mobility.

Comparing the Totals and Making Conclusions:

Once both shows have been run and done, sales will need to be totaled and standardized into ratios for comparison. The ratio will be total sales as compared to table fees.

Show A: Total sales/$98

Show B: Total sales/$186

So, for example, a person making $150 at Show A would have a standardized score of 1.53, and a person making $150 at Show B would have a standardized score of 0.81.

If the standardized scores are on average higher at Show A than Show B, that can be taken as evidence that my hypothesis that Special Guests can have a negative impact on the sales of paying vendors is true. If the standardized scores are similar or greater at Show B than A, then that’s evidence that I’m full of shit. (‘sOK. I can own it.)

Who is going to pay for all of this?

I see two options for turning this experiment into a reality. The first would be to actually run the shows myself as a for-profit effort. That would entail eliminating the honorarium for “paying vendors” and actually charging for tables. I would probably tweak things to lower the table cost if this was the case, seeking sponsors or charging admission to customers. The obstacle would be convincing vendors to share their sales information with me without a cash incentive. It’s an understandably private thing.

The second would be to either start my own nonprofit organization (NPO) or team with an existing NPO. The NEA gives grants for arts-based nonprofit organizations (NPOs) to conduct research, including social experiments. The advantage of teaming with an existing larger NPO would be that it would bring some credibility to the application and experiment process. The NPO in turn would be able to use the information gained as a resource for self-evaluation in addition to increasing their budget and increasing their capacity to gain matching grants.

The NEA grants also require published peer-reviewed papers, so I would need to publish a full paper about the experiment. This would likely require me to team up with more established academics.

To What End?

The thing about throwing out a hypothesis is that it prohibits making conclusions. Performing research and comparing the data to a model can generate correlations. Performing experiments can show evidence of causation. Creating a hypothesis is an opening door to more work. That makes it fair to ask “to what end?” should that additional work be conducted?

In my 2020 Comic Artist Survey, 45% of the respondents listed comic shows as a source of income. Nearly two-thirds of these respondents desired expressed values of both efficiency and equity from NPOs in the Comic Arts community, which in the context of this essay would include comic shows such as San Diego Comic Con, SPX, CXC, MOCCAfest, and others. These artists would benefit from information collected researching possible market failure at comic shows. It would certainly be more reliable and less clique-ish than bar-room post-show chit chat.

It is worth mentioning that comic shows are selling two very different services to paying vendors. The first and most obvious is their spot on the market floor. Comic shows are providing artists an opportunity to enter a marketplace and earn some money. The second, less obvious, service is that comic shows are selling social experiences, including a degree of social status. In my survey of comic artists about their experiences at comic shows, sales at comic shows, while important to most respondents, were not as important overall as meeting new buyers/fans and community time with fellow artists. Having fun was also more important overall among respondents than sales. Also, artists attend comic shows as fans/customers significantly less often than as paying vendors or Special Guests. This indicates that there is social status inherent to the experience of vending at a show. It opens up opportunities for communication and entertainment not available to fans on the other side of the table. It would be easy to use this social aspect of comic show vending to frame the information asymmetries created by Special Guests as unimportant, the friendliest devil’s advocate position being “Comic Shows aren’t about making money, they are about community.” I would submit that efficiency and equity issues still apply. The efficiency issue is that sales at a comic show offset the price of vending. If an artist experiences fewer sales, the transaction cost of joining that community goes up. The equity issue comes into play when one stakeholder is benefitting at the expense of another, such as when/if a Special Guest causes a reduction in sales for paying vendors.

There is a necessary element of caveat emptor that artists need to consider when paying to vend at shows. There is an inherent principal-agent issue at play where the comic shows are making decisions that affect paying vendors based on the show’s needs and goals versus the paying vendors’ needs and goals. This principal-agent issue shouldn’t be extended to the nth degree to vilify the people running comic shows. I personally believe that most of the people running comic shows are earnest in their desire to grow and augment the community both socially and economically. I do, however, think it’s time for comic shows to engage in some self-examination. Comic shows have gone from being hustles by ambitious and smart fans, both good and bad connotations of hustle intended, to become institutions in the community. In the case of private sector (for-profit) shows, it is important to address efficiency issues to ensure the continued health and ongoing profitability of a show. If the fees paid by vendors consistently lag behind the sales they earn, eventually attrition will set in despite the external benefits to artists that vending provides. NPOs that run comic shows should pay particular attention to the idea that they are perpetuating inequitable and inefficient market places. The role of NPOs is literally to address such things.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply