When Daniel Elkin offered me the opportunity to have a group discussion with Hannah Berry and Katriona Chapman about our similar artist survey research and subsequent reporting I was excited. I’m a big admirer of both creators! I got so excited that in my reply to the group email I let slip a fairly oblique and distinctly out of context Rolling Stones joke. You see… The request was framed as the three us getting together to discuss “next steps” for our mutual research and goals for the comic arts community. I asked if the idea was to lock the three us in the kitchen until we came out with some songs. Which is supposedly what Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham did to Mick and Keef in an effort to generate some original material and end the Stones’ reliance on American blues and R&B covers. My joke was a shameless hipster dog-whistle. Kat, for the record, definitely heard it. Hannah and Daniel may have heard it but were too busy rolling their eyes at my rock-n-roll-nerd tomfoolery to respond. Thankfully no one called the conversation off after I exposed myself as a hipster of the shameless variety.

The discussion itself happened not long afterward. Via Zoom. On the same day that a mob of bellicose Trump supporters turned insurrectionist in Washington DC. I don’t know if that affected the conversation or not. I had been avoiding the news as best I could up to that point, but was definitely upset by what filtered through to me when I peeked in on my social media accounts. Which is to say I was a little off my game, I think. Plainly, it’s often hard for me to put thought into the plight of comic arts when the larger, broader inequities of society are on full display. Living wage page rates are important to me, but on that day that was probably eclipsed by my fear of my country plummeting towards fascism thanks to an empowered lunatic fringe.

Thankfully, failed rock-nerd jokes and insurrection weren’t enough to bring a full stop to our discussion.

Just who was involved in this discussion and why?

The conversation, by necessity, starting with some “getting to know you” type elements. Hannah and Katriona know each other fairly well already, but they only knew me from a couple of emails and Facebook posts. I had considered coming up with some sort of icebreaker activity or game just to make sure we were all comfortable (dirty secret, I really like those kinds of corporate-retreat style games. My former coworker, Jess, at the Affordable Housing Trust was great at coming up with and leading them). Luckily, I think that all three of us clicked pretty well without drawing and sharing pictures of where we think we’ll be in ten years or anything like that.

For those of you who aren’t necessarily in the know about the conversation participants:

Hannah Berry: Hannah is an award-winninggraphic novelist and cartoonist with works including Livestock, Adamtine, and Britten & Brülightly as well as the Vox Pop cartoon in the New Statesman.Hannah isthe current UK Comics Laureate, a position whose responsibilities include acting as an ambassador for the comic arts with a focus on their ability to improve literacy. It was in Hannah’s capacity as Comics Laureate that she conducted a comprehensive survey of UK comic artists in an effort to take a snapshot of that population in terms of identity, income, and social status. Hannah also subsequently led four on-line discussions with UK artists to review and interpret the results of her survey.Katriona Chapman:Katriona is also a cartoonist, zinester, and graphic novelist. Her graphic novels include Breakwater and Follow Me In and her list of self-published zines is as long as my arm.(I’m 6 foot somethin’, so my arm is pretty long). Katriona is head of marketing at Avery Hill Publishing. Katriona took on the monumental task of creating a comprehensive write up of the four group discussions that followed the UK artist survey.

Ken Eppstein (Hey! That’s me!): I’m a comic artist and zinester who runs the small press effort Nix Comics. I am a former comics retailer (brick and mortar and online) and have worked many years in the nonprofit sector. I often incorporate elements of my nonprofit experience into my comics work. In 2020, I began an independent comic arts research project which included a survey of comic artists with similar but less expansive content that Hannah’s.

The proposed intent of our discussion was to discuss future works on behalf of comic artists and the artform itself based on our similar survey work. I don’t want to spoil the ending, but we didn’t come up with a course (or courses) of action that will “save comics.”

Motivations:

Hannah’s first question to me was why I got involved in doing this type of research. The answer to that is because the comics community has really become my family. My chosen family. I feel like that family is facing a lot of social and economic problems and research is required to start the three-step process of framing those problems, solving those problems, and implementing change.

The discussion was very loose and the subject matter flowed and ebbed, so I didn’t get to ask Hannah and Katriona about their own motivations. Luckily Hannah’s website has notes about her motivations in a background section about the survey. To put it into way to short a form, Hannah’s motivation stemmed from her personal economic difficulties as a graphic novelist and a desire to know how widespread those issues are among her peers.

Katriona’s motivation to take on the immense task of compiling the information of the four UK artist discussions will have to remain a mystery to me until our next group meeting. She did say during the conversation that “I always thought I wasn’t great at having ideas, but I’m great at organizing other people’s Ideas,” which, by the way, I don’t believe given the length of her writing credits, but is in a way a source of motivation. Sometimes you help just because you’re the person who knows how to get things done. I definitely identify with that.

Surprises:

One requirement for doing research of any sort is a willingness to be surprised. “Preconceptions are made to be broken” is a good philosophy to embrace when working on the behalf of underserved populations. Particularly in terms of research via survey, the expectation is to be surprised. Surprised by the answers. Surprised by the community’s response to those answers. We all have our preconceptions of what the comic arts community looks like and how it acts, so we ask questions in surveys that will either help confirm our impressions or dismiss them.

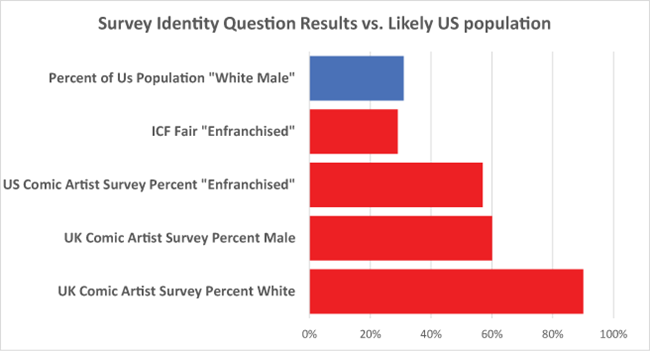

The one response area that all three of us were surprised about was the lack of response by the historically disenfranchised: identity groups that are either or both underserved and discriminated against. I was surprised given the response to my question about belonging to such an identity in my initial Indie Comics Fair survey: around 70% of my respondents stated that they belonged to such a disenfranchised identity. Hannah and Katriona were surprised based on their string connection to the small press and indie comics community in the UK, which is notable for its diversity. There was simple math involved with our assumptions as well. For example, by some accounts, white males are only around 31% of the United States population, so it is easy to expect that their (our, if I’m to phrase it in a less detached way) representation should be roughly equivalent. That was not the case among our respondents.

The question with this “surprise” is, do we have an accurate but disappointing result in our surveys, or do we have a sampling error issue? In support of the results being a sampling error, it is historically difficult to engage disenfranchised stakeholders. They are understandably cynical of attempts at engagement given a history of exploitation and abuse. I have been advised personally to remember that the more disenfranchised identities a person belongs to, the more difficult it is to engage with them as the issues that create cynicism add up. Along those lines, Hannah suggested in our conversation that some may be reluctant to claim the additional identity of “comic artist” as it adds to the complexity and rigor of their intersectional identity.

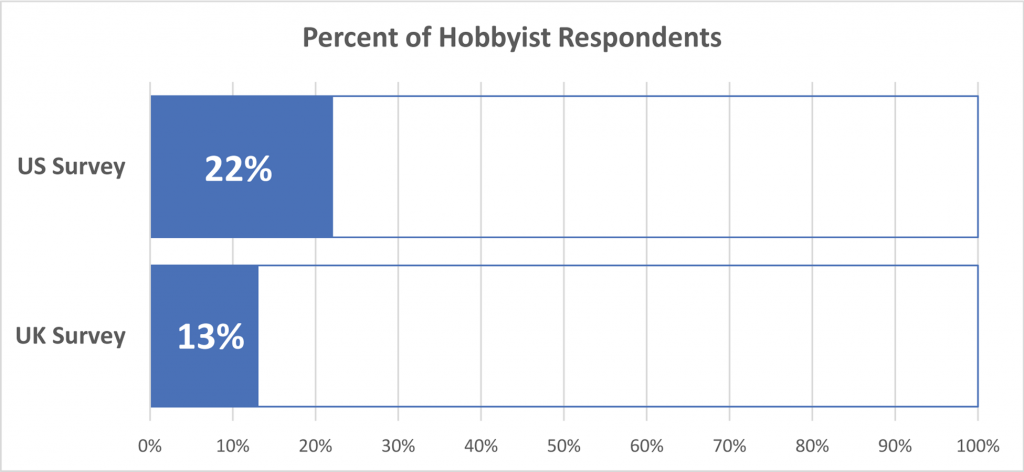

In the context of surprises from survey report readers, Hannah mentioned that she had received pushback from some professional artists for including hobbyists in the survey recruitment. They felt that the presence of hobbyists in the report skewed the survey results. For reference, the UK survey had 13% of respondents self-designate as hobbyists, and I identified 22% of my respondents as hobbyists based on their responses to income source questions. Hannah did not express any regrets over including respondents from all tiers of professional life but did acknowledge the professionals’ voice. I wonder if I was saved this pushback thanks to my stakeholder-based approach which asked questions that helped me define “Professional,” “Hobbyist,” and the gray space in between. Regardless, I would say to the artists who felt that the stakeholders who edged more towards the hobbyist end of that spectrum need to be included in all research because they inhabit the same social and economic space as professional artists. Hobbyists share “eyes” on the internet and help shape the perception of comic arts to the broader community. Hobbyists also compete to some degree for income when they do enter the job market or apply for tables at comic shows. In short, hobbyists are impactful and ignoring them would be ignoring a great deal of context for any problems that professional comic artists need to be solved.

Hannah and Katriona also pointed out that it’s from the ranks of the hobbyists that professionals generally come. Most comic artists at some point early in their career perform work at a discount rate, sometimes even for free, as a foot in the door. It can be argued whether or not it’s an effective or healthy strategy, but it’s a reality. Katriona went on to point out that this is a phenomenon that crosses artistic fields, citing her experiences in the theater world as an example. I would definitely agree with this estimation, which in particular makes me think of the cross over between Nix Comics and the music scene in Columbus. Musicians in local music often perform on other artist’s albums or at live shows without compensation. It’s the rule of thumb, in fact, as opposed to the exception (Bob Ray Starker once told me that pay for the work he’s done for Nix Comics has exceeded any money he’s received for a decades-long musical career. Still can’t quite wrap my head around that one).

Barriers:

We didn’t set out to identify barriers to solutions facing the comic arts community, but they certainly started popping in our conversation. I think it’s a tendency that all would-be advocates and activists fall into the habit of analyzing problems in terms of barriers, even before all of the facts are in. In particular, social and economic barriers are the most intimidating part of problem-solving. They’re inevitable and can’t be easily excised because social ills are insidiously interwoven into the make-up of our society.

“Let’s solve comics and then we’ll overthrow the capitalist system.”- A friendly bit of sarcasm from Hannah Berry.

Hannah’s bon mot about capitalism was inspired by an artist Katriona spoke to before their group discussion about money in the comics community. The artist felt that the primary problem was the inequity and exploitation inherent to the capitalist system. I received several similar personal messages while recruiting for my survey. I don’t want to speak for Katriona and Hannah, but I’m definitely sympathetic to that line of thought and call for change. Pragmatically speaking, though, there is a reality that capitalism is the mechanism that we are stuck with for day to day survival in our society. The tension between the desire for social change and that pragmatic reality is a hard and painful line to walk. I submit that we (researchers, advocates, artists) do what we can on a case by case basis to improve ourselves and the community we serve, helping them navigate the negative aspects of our capitalist society, and hope that the policies and practices we create diffuse outward to the rest of the world. The Rolling Stones came out of the Kitchen with new pop songs, not a whole new kind of music.

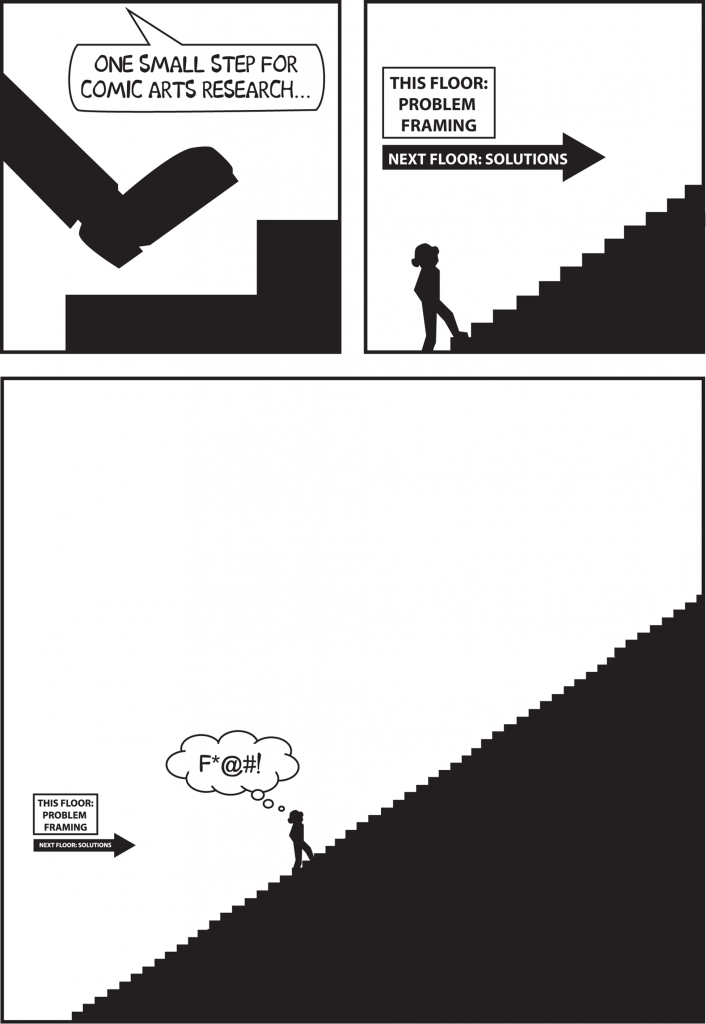

The bigger problem with getting caught up in thinking about barriers to solutions early on is that they usually come into play later on in the process for social change. While there are no strict rules for activism or advocacy, successful efforts for social change can usually be viewed as a three-step process: problem framing, followed by proposing solutions, and ending with solution implementation and management. Barriers are only fully understood if the problem framing step has been done to the fullest possible degree. If the barriers aren’t properly framed, then solutions will be inadequate and implementations will be rife with negative spillover effects.

Along those lines, I brought up the artist who framed the issue of low page rates as being the result of younger artists taking lower wages, thereby effectively boxing out older artists from the job market. I don’t want to vilify the guy who said that. I don’t know his personal context and I’m sure that this very much feels like the case, but I find it an unfortunate way to frame the problem. Is the problem that younger artists are undercutting older artists, or are there just more artists than ever now and that invisible hand has tamped wages down in response to the greater supply of labor? In an industry that was built on the exploitation of artists, that seems more likely to me. Framing the problem as a market failure has the benefit of creating allies rather than being fractious. Younger artists and older artists together have a greater voice for change that the groups do individually.

Hannah concurred, further stating that “It’s odd to put the blame on people who will take a lesser amount of money for the honor of doing the work and not put it on the publishers who are willing to pay that little money.” The problem framed as a need to have more responsible behavior from the employers in the comic arts community unifies the young and old artists and transfers some of the burdens for a solution to the empowered stakeholders, the publishers.

In our discussion about this issue specifically, we even went an extra step by stating we shouldn’t vilify all publishers. We all agreed that many publishers act earnestly in regards to artists, paying what sales allow. Those publishers should be pulled in as allies as well.

“We run into so many people every day and when you tell them you make comics and they don’t know what that is.” -Katriona Chapman

There seems to be a very different perception of the status of comic arts between the general public in the US and the UK. To me, this was the most interesting facet of our discussion. The only times that I remember someone being confused over what I do are those where the semantics of comics versus comedy get mucked up. Sometimes people think I do stand up or improv until I clear it up, but they never are perplexed by just what “comics” are. I’m not sure where that cultural gap comes from but I can see how it would certainly make the barriers to acceptance that much steeper.

Thinking on it, my experience is very different. I rarely have to answer the question “what do you mean you make comics?” I do, however, often have to engage in a conversation where the other person has a preconception of what comics. That preconception often presents itself in a position of “I’m not a comics person” on the part of my conversation partner. I think of the two problems, someone not knowing what comics are versus someone stating that they aren’t a comics person, I would prefer the former. The former allows me to present myself from a position of knowledge and love, but the latter requires a more defensive posture wherein I either walk away or swallow the feeling that I’ve just been low-rated and attempt to be persuasive about the value of my chosen artform.

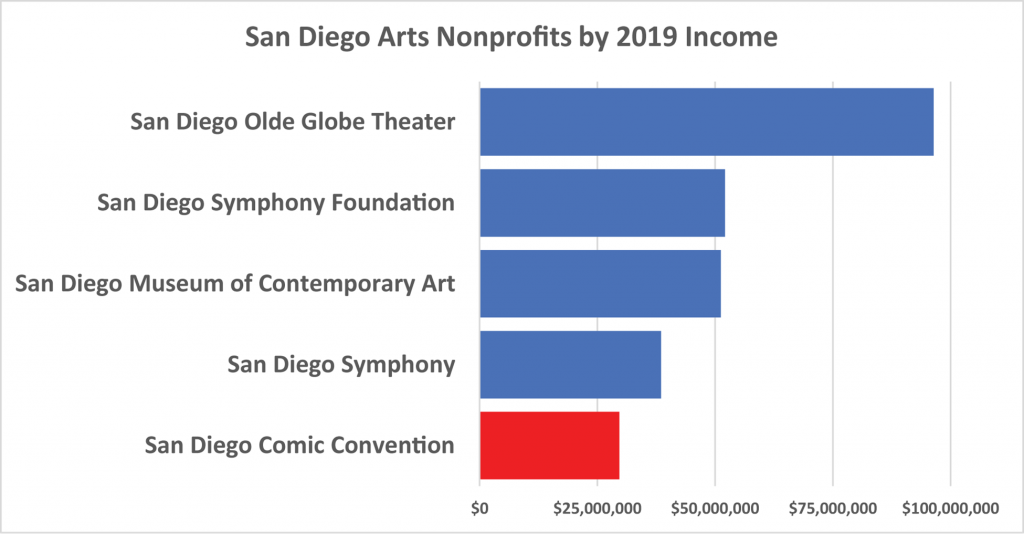

What both points of view illustrate, though, is that there is a barrier in the form of a hierarchy among art forms and media. In some ways, the comic arts lives in a diminished position within the world of arts and media. It’s a hierarchy and, at best, comics are somewhere in the middle in terms of importance. Katriona pointed out that there are cultural institutions that support arts like film and fiction writing, but there’s not really anything like this for comics in the UK. In the US there are some institutions that support comics arts, notably the Billy Ireland Museum and Cartoon Library if you’ll forgive a sudden bout of homerism, but nothing on the scale of the institutions that support older artforms that have a history of patronage. In terms of Nonprofit organizations, San Diego Comic Con is the largest NPO in the U.S. that could be considered a “cultural institution.” However, it is only the fifth-largest arts NPO in the city of San Diego.

Katriona had a very punk-rock point about these large institutions, though. The comic arts have their roots in the low-brow and DIY. Do they need or even want the aid of large formal organizations to continue? Such patronage comes with expectations and pressures which could constrain the wild and wooly nature of the artform. Hannah, conversely, sees room for both the high and low brow in the artform, particularly if the high-brows come knocking with opportunity at their side. I tend to agree and think that we should address the problems that come with institutional constraints after we have some offered. It’s a cart before the horse sorta thing.

Cultural institutions do seem to be popping up in the UK. Hannah said that the Society of Authors has formed a comics creators network trade union for writers in the UK called the Association of Comics Creators. This provides UK comic artists access to a large entity to resolve issues in a community, even though as artists they may or may not be members. Katriona noted that these types of advocate organizations can break through the isolation felt by comic artists, as well as create a hub for information about the industry.

On a less formal/organizational level, Hannah is very interested in getting comics on more shelves in bookshelves. Not just having comics stocked in bookstores, but literally on more shelves in terms of their location within the store. Biography comics in the biography section, science fiction comics in the sci-fi section, etc. Comics are often marginalized in these stores by virtue of geography: they all live in a lonely often unvisited “graphic novels” section. I’m of two minds on the diffusion of graphic novels outward from the graphic novel section. The first is, yes… it’s a form of representation. Putting those comics in front of the eyes of potential readers is a great step. The second, though, is that representation by itself isn’t sufficient for change. There needs to be a more active effort to get people to engage with what the comic arts bring to the table that conventional books do not (there I go again, thinking about barriers when we should be problem framing). Anyway, it doesn’t stop at brick and mortar stores. Hannah also wants to use her status as the UK comics laureate to pitch companies like Storygraph, the heir apparent to Goodreads, to break those format based biases in favor of including comics in all genre-based searches.

Conclusion:

I know I spoiled it already. We didn’t figure out how to fix comics anywhere in the course of our hour and a half long conversation. Honestly, I would have stayed on longer to try and figure it out, but the fall of democracy was on TV and I didn’t want to have to watch it in reruns. I will say, though, that the assault on the capitol building did provide a reminder that some problems are too big to be framed properly, and when improperly framed lead to disaster.

Problem framing being the thing, I think the immediate need in the comic arts community is still for more information. Who are the stakeholders? What exactly are their stakes? How do those stakes create biases? What talents do they bring to the cause? It’s a little tough, I think, for folks like Hannah, Katriona, and I to finish up massive time-consuming, work-intensive projects like our surveys only to realize that they are only baby steps on a much longer journey… But that’s the case. The next steps are still the same as the first steps. More research and efforts to increase transparency within the industry.

We wrapped up by discussing the fiscal challenges of taking those steps. We’re talking about taking a journey and, for a journey, you need supplies and for supplies you need money. Otherwise, you have to eat only what you can hunt and gather along the way, not to mention sew your own jackets when it gets cold and brush your teeth with rosemary twigs. We definitely acknowledged that there’s a rub in asking the comic arts community for help with funding. Comics folks are generally broke. This led us back to talking about larger institutions and organizations, with a little bit of focus on academia and scholarly grants… But all three of us were fading a little at that point and wrapped up the Zoom session.

We plan on meeting again to build on some of the ideas we discussed. I look forward to it!

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply