Introduction:

After completing my 2020 stakeholder survey of artists, I had a few people ask me something akin to “where are you going with this research?” Smart people. People who know me (i.e. people I trust to have insight). It’s a good idea to have those people in your life, if for no other reason than when they ask what your intentions are it’s a good sign that no one else has any idea what you’re doing or why.

Here’s the Scoop: I’m on a mission to gather and present information about the comic arts community, focusing on the desires, needs, strengths, weaknesses, barriers, and passages of all stakeholders. The objective of providing this information is to provide tools and benchmarks for framing the social problems facing the comic arts community, proposing solutions to those problems, and creating a path for implementing those solutions. It’s my contention that without taking the time to conduct this research, the acts of problem framing, problem solving, and solution implementation are severely hampered, if not completely erased. It’s also my contention that despite the well-documented benefits of the arts in general and comic arts in specific, attempts at positive social change for the community is impaired by a history of exploitation, non-transparency, bias, and market failure.

Here is a good for-instance for you: In 2012 the US Copyright office introduced a bill for a droit de suite law. If you are unfamiliar with the term, it is basically the idea that each time an original work of art (i.e. painting, sculpture, or, pertinent to this essay, an original page of comic art) is resold, the artist would be due a royalty. The idea behind the bill was that writers and artists who see royalties as works are reproduced see continuing benefits as their work increases in value, but artists who create singular pieces of art do not. The bill never made it out of committee for a vote, with the legislators citing a lack of knowledge of the workings of the arts market as a barrier to creating an effective and fair law. Crazy, right? Despite zillions of public art auctions every year, Congress didn’t think it had enough information to enact a law that the copyright office itself thought was only fair.

It’s because of the negative aspects of comics history that I have begun by researching artists. They are the driving force of the community (no artists equals no art, after all), but they are also frequently the first group harmed by exploitation and market failure. Comic Artists live in a uniquely awkward position of not only needing to be treated fairly in terms of pay and benefits, but also being vulnerable to exploitation due to getting personal utility from being an artist. I know its sounds mean, but basically comic artists are often willing to take the short end of the stick just for the honor and joy of getting to touch the stick.

I have also started examining nonprofit organizations (NPOs) as the most likely agent of change in the comic arts community. This is because NPOs are best suited to address issues of market and societal failure. They are the formal manifestation of social movements and are free to act independently of constraints of the profit-hungry market sector or the majority serving government sector. NPOs aren’t a perfect tool, but they seem to me to be the best thanks to their unique “third” sector position. Also, please note that for the purposes of my research and writing, I am using NPO to include any social benefit actions that have a degree of structure and formality, as opposed to strictly those who qualify as tax-exempt by IRS standards.

It’s by examining these key stakeholders and the information they provide that we can begin to create that positive change.

What does that look like, though?

The best way to show you my intent is to take a sample social problem and use some of the information I presented in my 2020 Comic Artist Survey to parse out some of the options for addressing that problem.

Problem Statement:

Page Rates offered by publishers do not equate to a living wage for many artists.

What Constitutes A Living Wage:

A living wage is defined as the minimum wage an individual requires to pay for all the basic necessities in their life. This definition prohibits a flat national living wage rate as the necessities of life vary from household to household and location to location. A married person with no children living in Columbus, Ohio has different expenses than a single parent of three children in New York City. Generally, though, living wage estimates are made based on the assumption of full-time employment and can be given as hourly rates or annual salaries. For purposes of this exercise, living wage estimates will be made using the MIT Living Wage Calculator.

A living wage should not be considered synonymous with a fair wage. A living wage is meant to be a basement estimate of a deserved salary. To create fair wages, an employer would increase salaries based on a pay scale that took into account factors that enhance an employee’s value, such as experience, versatility, and reliability. A fair wage would also avoid discrimination and cultural bias. The research published on the Litebox and Creator Resources websites is an example of studying the frequency of fair rates.

What is A Page Rate:

As the term would imply, it is the payment rate that an artist receives per completed page of art turned in to a publisher. Generally, this work is contract-based and can be sporadic. Page rates differ by type of artist. For example, pencilers generally receive more than letterers. The rate of pay roughly equates to the amount of time it takes to complete a page. There is some research and published information on page rates, but the information is generally considered proprietary by both publishers and artists and not readily shared.

Average page rates are difficult to estimate or make assumptions about. Fairness is difficult to establish due to limited information for making comparisons. Equivalence to a living wage can be projected by making assumptions on expected productivity (i.e. if a penciller is expected to complete one 20 page comic per month, a page rate can be determined by figuring out what the living wage for the individual would be for a month and dividing that amount by 20).

If you are interested in seeing how this is drawn out, here is a sample grid using a few examples from the MIT calculator and the US Bureau of Labor Services average salary for an “artist” as a reference point.

The Context of the Problem:

The idea that work in comics does not provide a living wage is not a new one. It’s been an issue since National Comics paid Siegel and Shuster in $17 worth of beads, mirrors, and trinkets for the rights to Superman (I’m joking, of course. They paid something like $130, or around $2,000 in modern money. It was Bob Kane who paid Bill Finger for Batman in beads, mirrors, and trinkets).

My own survey showed that a high percentage of artists supplement their art income with a full-time and/or a part-time job. I guess you could argue that in the case of full-timers, the artwork is a side hustle supplementing the day job, but you get the idea. Comics work can be sporadic and not pay well enough to support a person even if consistent.

Recently Hannah Berry published the results of a survey similar to mine. Hannah’s survey was more extensive in its questioning and more specific to artists living in the United Kingdom. One of the survey findings was that those artists did not earn a living wage with their comics work. Similarly, Sasha Bassett’s 2019 Comics Workforce survey study examined comic artists from the point of view of potentially creating a comic creator’s labor union.

Defining Stakeholders

Comic Artist Identities:

As they are the focus of my 2020 Survey, Hannah Berry’s UK Artist Survey, and Sasha Bassett’s 2019 Comic Workforce survey, these are the stakeholders that we have the most data on. In the first part of my Artist Survey, I focused on ways of dissecting the identity of “Comic Artist.” The importance of this becomes apparent when it comes time to create a problem statement. In this case, it is worth noting that that the problem revolves around a distinctly professional issue: Page Rates. This indicates that the spectrum of Comic Professional to Hobbyist is the best place to start with stakeholder identification. Specifically, the needs of Comic Artists who are Professionals and who have professional aspirations (Semi-Professional for purposes of this essay) that need to be addressed. Hobbyists are largely unconcerned with page rates.

Once the basic identity is decided on, it is important to note qualifiers to that identity for purposes of this examination: For instance, the page rates issue applies mostly to artists performing contract work for the publishers of monthly direct market comics and some of the larger independent crowdfunding efforts. Some of those direct market publishers (Image most notably) use a profit-sharing model, bypassing page rates. Most graphic novel publishers use a system that involves an advance and royalties on further sales. So for purposes of this problem statement, I will define comic artist stakeholders as follows:

Professional: Artists who work full time on comics and are paid on a page rate basis. Usually, comic arts are the sole source of income, although income may come from many comic-related sources (royalties, comic cons and festivals, commission work, on-line sales, self-publishing efforts, et. al.).

A notable tendency for Professional respondents in the survey is a higher likelihood of desiring an NPO to function as an advocate, and they more highly desire the value of empowerment than the field of artists as a whole. However, Professional survey respondents also highly desire Value Guardians NPOs and are also less likely to desire transformation as a value from their NPOs, indicating that, as a group, Professionals are more likely to resist innovation when options that improve or supplement the existing systems are available.

Semi-Pro: Artists who work part-time on comics and are paid a page rate. Generally, these respondents have other sources of income. This identity category would include artists who are aspirational in their artistic career motives, and so the lack of page rates that equate to a living wage would be a barrier to “quitting the day job.”

As the largest stakeholder group, Semi-Pro respondents will have a relationship to NPOs similar to the overall results of the survey, which include a high desire for NPOs that function both as Value Guardians and Advocates, but a majority of them desire to also see Service Providers and Service Innovators. Semi-Pros have a greater desire for transformation than Professionals and Hobbyists.

Hobbyist: Artists who see no income from their comic art and, so, are not directly affected by page rates. Hobbyists are, though, a notable community voice and important factor in the comic art form if not the comic art industry.

Hobbyists more or less fall in line with the Semi-Pros in terms of how they would like to see comic arts NPOs function, but they do have some considerable differences in values, most notably a strong lack of interest transformation.

NPO IDENTITIES:

NPOs are also stakeholders in working towards a living wage page rate, as they are the most likely engine for change and a source of support while change is awaited. To my knowledge, there hasn’t been any sort of effort to interview or survey comics NPOs in the same manner as the artist stakeholders, but as NPOs are generally forthcoming with methods, mission statements, and values, insight into their input is more transparent than opaque. As a refresher, below is a list of the stakeholder identities I have chosen to define NPOs in the context of my current research, this time including the strengths and weaknesses inherent to each:

Value Guardian: the NPO champions the creation and consumption of the comic arts to the general public to create greater understanding and deeper interest. Value Guardians are popular among artists, just over 71% of the artists that I surveyed wished to see Value Guardian type NPOs in their community. For artists, the thinking is likely that Value Guardians support the artform itself, creating an “all boats rise with the tide” type environment. This is reflective of artist confidence in the value of the artform form as a whole as well as in their own work. This is supported by their high rate of desire for NPOs that increase the number of buyers and inform buyers about their work (68.20% and 62.76% in my survey).

The main weakness of Value Guardianship is that it is prone to the creation and preservation of institutions, hierarchies, and canon. The argument can be made that rather than creating an environment where all boats rise, Value Guardians operate on more of a trickle-down basis, with only the boats that rise being the ones lucky enough to be where water is allowed to pool. Value Guardians are very democratic in nature, which is great if the beneficiaries fall into some sort of majority. Not so great for minority stakeholders.

Advocate: the NPO speaks to power on behalf of comic artists, including, but not limited to, the government, courts, comic arts businesses, and other NPOs. Advocacy was overall the second most desired NPO function in my survey, with a slightly higher than average desire for advocacy by professional stakeholders. This desire is likely the result of a trust in and love of the artform being in tension with a deserved mistrust of the art comic market and industry. This position is supported by the findings in Hannah Berry’s UK Artist Survey.

Among the weaknesses of Advocate NPOs is a relative lack of resources. Value Guardians can often rely on sponsorship from the institutions that they support and volunteers from the fans of those institutions. Advocacy groups must mostly rely on the resources of the groups and individuals for whom they are advocating… cash and time-strapped artists.

Service Innovator: The NPO provides services that are substantively different from similar for-profit services to achieve positive outcomes for artists, such as research into possible alternative market models for the comic arts. Service Innovators allow for solutions that circumvent or defy the status quo of the comics industry and community. They are appealing to comic artists who value adaptability and transformation in their NPOs.

Due to the inherently experimental nature of innovation, Service Innovators do face an issue in that many comic artists actually value efficiency and effectiveness more than adaptability and transformation. Innovative services come with barriers in the form of a higher learning curve for beneficiaries (lower efficiency) and less consistent positive outcomes (lower effectiveness).

Service Provider: The NPO provides services that mirror for-profit services, but use the advantages of nonprofit service to achieve positive outcomes for artists. Where Service Innovators attempt to create positive outcomes through transformative and adaptive initiatives, Service Providers operate more on a supplemental basis, creating positive outcomes through means familiar and standard to beneficiaries.

Service Providers face a problem in that they may generate positive short-term outcomes, but they may have a negative spillover effect of preserving the status quo of a comic art market prone to market failure and exploitation. Service Providers, while desired by a majority of the comic artists that I surveyed (54.08%), were the least desired NPO function. This is also likely reflective of the tension between the love of the artform and the distrust of comic arts institutions found in Hannah Berry’s survey.

Social Benefit versus Charity:

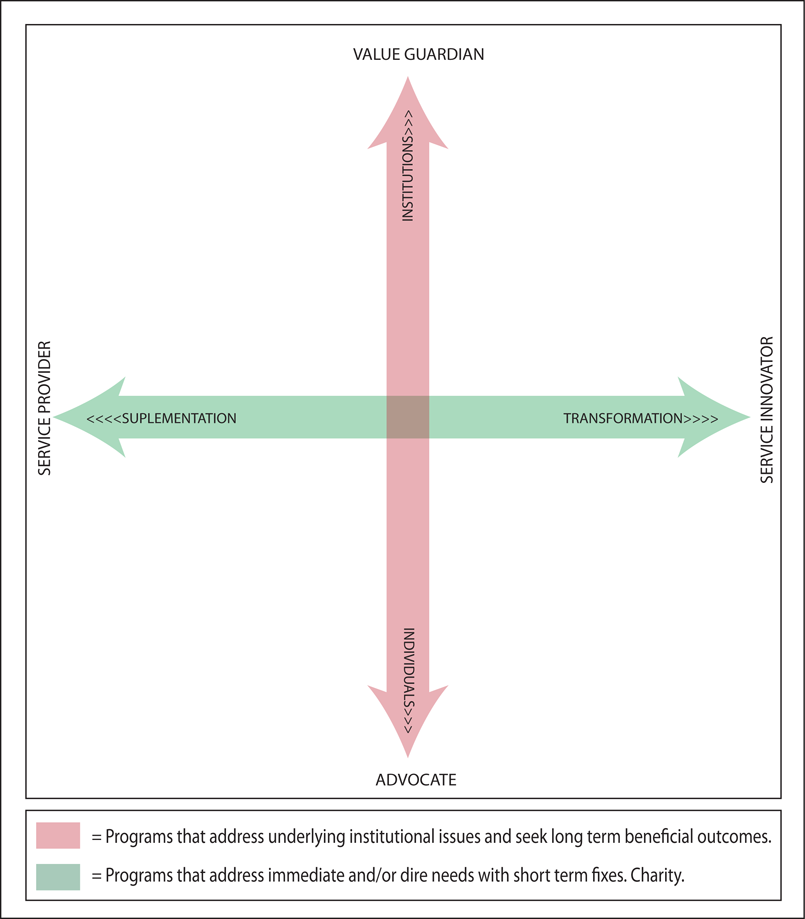

Value Guardians and Advocates tend to work on programs that provide lasting benefits and address underlying structural problems in the comic arts community. Value Guardians tend more towards programs that enhance the community as a whole, while Advocates stress equitable and fair treatment for individuals and groups that make up the community.

Service Providers and Innovators tend more towards addressing immediate issues and needs through charity work in other fields. Innovators tend towards more transformative methods while Service Providers supplement existing processes.

Labelling NPOs:

So which NPOs are which? Below, I have a graphic model meant to help you analyze NPOs based on their programs and initiatives. I’m gonna call it the NPO Function Cross because I think it sounds cool. The idea is that Value Guardians and Advocates exist on a spectrum of work that seeks to address the underlying issues of the community between supporting the institutions of comic arts and supporting the individuals who create the art, represented by the green vertical part of the cross. The pink horizontal part of the cross represents the work of Service Providers and Service Innovators addressing immediate needs on a spectrum between supplementing existing services and transforming existing services. This creates a natural grid that can be used to plot NPO activities.

A person can then analyze an NPO based on where their programs fall on the grid. For example, I have based the cross below based on the programs and initiatives listed on Short Run Seattle’s website. Based on the information they have provided, it would be reasonable to consider Short Run as an organization that leans towards being an Advocacy group and Innovator.

It’s important to note that these categories are not meant to be hard and fast. A Value Guardian could provide a service to advance its mission, for example. These categories are meant to be reflective of the objectives of an NPO as stated in their various missions and programs. The use of the identity labels is an expediency and should be considered a fluid thing due to the subjective and various nature of NPO programs (i.e. what is a Value Guardian to me may be an Advocate to you. That’s… y’know… legal. The important thing is to talk about why we have that opinion).

Other Community Member Stakeholders:

This is the group of stakeholders that there is the least available information for. Just as Hobbyists have important and influential voices, other stakeholders are tacitly implied by the problem statement and should be considered when framing problems and solutions because they have a direct impact on the feasibility of implementation of any planned actions or programs.

Publishers: In this case, Publisher will be used to describe the entities paying the page rates to artists and one of the driving forces for generating income in the community. Publishers provide the capital and production for the comics market. As the primary investor in artwork, Publishers are also the primary risk-takers, gambling that their chosen inputs (comic artists) will generate enough revenue to continue the process of publishing.

Retailers: Retailers, in this case, will mostly consist of comic shops in the direct market system (book stores generally resell graphic novels, which rarely use page rates). Retailers, dependent on consistent comic sales, will have a stake in program or activity that will change their pricing or access to products. Retailer resistance can be a difficult obstacle to overcome in implementation, while Retailer support could facilitate implementation.

Fans/Readers: These stakeholders are the customers of the Retailers. As comics are a desired commodity, not a need, Fans/Readers also have a stake in any program or activity that changes price or access. Just as is the case with Retailers, Fans/Readers resistance can be a difficult obstacle to overcome in implementation, while their support could facilitate implementation.

Government: The Government is a powerful stakeholder that has particular influence over the feasibility of any solution proposed by NPOs that requires legislative action or governmental approval. Unions for example. Advocates, in particular, need to establish good relations with, or at least understand internal the workings of, Government stakeholders.

POWER Vs INTEREST:

The most common way to gauge the relationship between stakeholders once they have been identified is a power versus interest grid. The grid is created by drawing an X-axis that represents power and a Y-axis that represents interest in a particular issue. Power is defined as the ability to create change on a given problem or issue, which increases as stakeholders are plotted more to the right. Interest is a measure of desire to see action taken on the problem or issue, the greater the higher the stakeholder is plotted.

The area inside a power versus interest grid is often divided into quadrants, with lower quadrants being considered “low” interest or power and the upper quadrants being considered “high” interest or power. Stakeholders may be plotted on the border of the quadrants to indicate non-monolithic opinions among individuals in a stakeholder group. As a shorthand, stakeholders are referred to by the quadrant they appear in as follows:

Subjects:

The stakeholders who have high interest in seeing a problem addressed, but low power for enacting change.

Players:

The stakeholders who both have a high interest in addressing an issue and have power to create change.

The Crowd:

The stakeholders who have low interest in seeing a problem addressed and have low power in terms of the ability to create change.

Context Setters:

The stakeholders who have low interest in addressing an issue, but do have the power to create substantive change.

Barriers to Solutions and Stakeholder Identity Research:

Having stated a problem and identifying the pertinent stakeholders, it becomes important to start examining the problem of a living wage pay rate. In this case, where the answer seems simple (pay artists more), we must look at the cultural, political, and economic reasons why a Living Wage Page Rate hasn’t already been achieved.

Complexity of the Comic Artist Stakeholder Identity:

A living wage is a fluid target, changing size and shape based on the needs and circumstances of the individuals being paid. This makes creating a proposal for page rates that equates to a living wage a difficult problem to solve with a single set solution. Using a system such as the grid I referenced above requires establishing the needs of the artists and weighing them against the expectations of productivity. Additional information would be needed to make a grid like this useful, though. How many comic artists live in a two-income household? How many are single parents? How many children do comic artists typically have? Where do most artists live? Once all of that is established, do you base a living wage on the individuals with the least severe set of circumstances, most severe set, or use some sort of median value?

Once the living situations of artists are determined, how do you estimate the expectations of workload? Is it reasonable to expect a penciler to do more than 20 pages a month? What about writers, colorists, inkers, flatters, and letterers? There are no industry standards on such things other than those implicit to monthly deadlines.

These questions are largely unanswered and it would require additional work to fairly assess a living wage page rate. My survey, along with similar resources such as Hannah Berry’s UK Comic Artist Survey and Sasha Bassett’s 2019 Workforce Survey, touches on these elements, but doesn’t address them directly or fully enough to equate the information to the creation of a useful living wage grid.

The survey work does, however, point to the problem with setting page rates that is somewhat outside the numbers. Comic Artists gain personal value from their work that lies outside the financial benefits, which leaves Comic Artists open to exploitation. For example, in my survey many artists reported working in excess of 40 hours on comic arts and many others reported working full or part-time jobs as well as freelance work. Presumably, most of these artists would not be working such long hours if page rates were based on a living wage based on 40 hours of work. In fact, 58.14% of the comic arts professionals I surveyed see a clear path to their artistic aspirations, indicating an overall contentment with the amount of work as long as it progresses them artistically. A notable correlation to that statistic is that approximately the same (59.52%) percentage of artists polled by Bassett consider working in comics a dream job. Simply put, there is a problem where publishers offering page rates are offering the short end of the stick, but many artists are willing to take it. They’re happy just to touch the stick.

Can the Comic Book Industry Afford To Pay a Living Wage?

Given that page rates apply mostly to the direct market part of the industry, which is currently in a state of contraction, it is important to consider whether or not the industry can support paying page rates that equate to any given standard of a living wage. The exact information on the expenses and revenues tied to each direct market title isn’t available. The best we can do is estimate based on information that is available. For example, in the table below I have estimated the expenses of making a single comic at various page rates and the number of copies that a company would need to sell at a wholesale rate to break even at those rates and compared that number to totals given in a single month of sales.

Estimated expenses for producing a comic with a living wage page rate

| Low-End Living Wage | High-End Living Wage | BLS Artist Median | |

| Penciler (1 expected per Month) | $75.00 | $485.00 | $205.00 |

| Writer (2 Expected Per Month) | $40.00 | $240.00 | $100.00 |

| Colorist (3 expected per month) | $25.00 | $160.00 | $70.00 |

| Inker (3 expected per month) | $25.00 | $160.00 | $70.00 |

| Letterer (4 expected per month) | $20.00 | $120.00 | $50.00 |

| Total per page | $185.00 | $1,165.00 | $495.00 |

| Total per 20 Page Comic | $3,700.00 | $23,300.00 | $9,900.00 |

| Total with 35% Overhead | $4,995.00 | $31,455.00 | $13,365.00 |

| # Needed to sell to Break Even at $3.99 Cover Price | 3,122 | 19,659 | 8,353 |

| Number of Books selling that many units January 2020 | 355 | 110 | 215 |

Notes on Estimates:

- The page rates above are from the grid I created based on the MIT Living Wage Calculator rounded to the nearest $5 increment.

- The low-end living wage is based on a single adult with no children household in Columbus, Ohio. The high-end living wage is based on a single adult with three children in New York City.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics page rates are based on the median annual income for artists listed on the BLS website.

- The 20-page count used is based on Brian Cronin’s 2017 CBR article.

- Overhead is meant to be reflective of the fixed costs of running a comic book publishing company, such as facilities, marketing, and salaries. as well as variable costs, such as printing and shipping, minus revenue generated by a comic through advertisers and licensing agreements. Actual overhead will vary greatly from company to company, so 35% is an admitted spitball number. It is, however, likely a generous spitball number. Consider for example, when DC Comics had 240 staffers in January 2019 before laying off seven. According to Comichron, DC had 104 titles for sale that month. That’s more than two staffers per title. Throw rent on those fancy California digs and you likely have some high overhead. The higher the overhead, the less likely it is a living wage page rate is achievable.

- Number of units needed to sell is based on the total expense of the comic book divided by $1.60. The $1.60 rate is based on the assumption of a cover price per comic of $3.99 and a 60% discount given to the distributor when purchasing comics for distribution.

- The number of books sold row shows how many of the 500 top sellers in January of 2020 sold a sufficient number of copies to, in theory, support a living wage page rate. This is meant to be a benchmark only, acknowledging that some of the books in the top 500 may be reprint material, pay artists on a percentage basis in the same fashion as Image Comics, or otherwise circumvent paying artists on a page rate basis.

These estimations imply that the direct market currently has insufficient sales to ensure across the board living wage page rates. At best, around 70% of titles in January 2020 could have supported paying artists the lower end estimation for a living wage page rate and less than half could have supported paying artists at a rate equal to Bureau of Labor Statistics stated median for artists.

Proposing Solutions:

The NPO Function Cross can also be used to examine potential programs and activities. In our example of a living wage, for instance, a person could plot the potential solutions and then consider feasibility based on a resource such as the 2020 Comic Artist Survey.

From Value Guardians

While Value Guardians were the most preferred type of NPO in the 2020 Comic Artist Survey, it would be easy to dismiss the role of Value Guardian NPOs in the role of supporting the needs of individual artists. By definition, they are the guardians of the value of all aspects of art form, not just the individuals who create the art. Advocates would be the type of NPO generally considered to be the guardians of equitable artist treatment, while Value Guardians tend to have more trickle-down missions: what is good for the art form and its institutions is good for the artists. Ignoring the importance of Value Guardians would be a mistake, though.

As the representatives of the institutions and overall culture of the comic arts, Value Guardians are generally the source of education and informational resources. There are currently some NPOs, academic institutions, and informal private efforts that, to some degree, track artist and artist pay information (Grand Comics Database, The Queer Cartoonists DB, The Cartoonists of Color DB, the Poopsheet Foundation, The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, The Michigan State Comic Book Collection, Litebox.info, and the Creators Resource Page to name a few). Individually, these efforts provide varying degrees of information pertinent to their own goals and missions but provide only a scattered and incomplete set of information as it would pertain towards living wages for cartoonists (the Grand Comics Database, for example, has a database of thousands of comics creators but doesn’t track which ones are currently active/working).

Key to the success of Value Guardians working on behalf of artists is finding an intersection point between their own missions and the high expectations of artists they are serving. 83.75% and 74.58% of artists surveyed reported desiring NPOs that expressed community and empowerment values, respectively. Additionally, 73.33% of artists surveyed desired NPOs to value both inclusivity and transparency. This suggests that Value Guardians seeking to improve living wage page rates should concentrate on projects that quantify not only the number of artists but also gives voice to their diversity of identity, strengths, and needs.

Suggested Value Guardian Activities to support a living wage page rate:

- A Comic Artist Census to determine the number of active artists and their economic/social status.

- A wider range survey of artists about their current page rates.

- A compiled history of page rates researched by interviewing artists about work history and by reading available sources such as comic arts histories, biographies, and journals/zines.

From Advocates:

The second most preferred form of NPO by artists in the survey would seem to the most appropriate type of NPO for helping establish a living wage page rate. The obvious and frequent form of advocacy called for is some sort of union or professional association/guild. In terms of U.S. nonprofits, those two similar-sounding things tend to be very different things in terms of the actions they may take. That is not the limit of advocative efforts. NPOs and artists alike should remember that often the types of actions that they might wish a large formal organization to take on their behalf can also be conducted as less formal individual actions. Like Value Guardians, Advocate NPOs need to focus on the strong desire of artists for community, empowerment, inclusivity, and transparency. Advocates face some common artist values that could present barriers to success, particularly when it comes to making changes. Transformation is important to a majority of artists, but just barely at 50.83%. Enfranchised artists (those who do not identify as belonging to a group that presently or historically suffers from bias or discrimination) only see transformation as a desirable value 40.44% of the time. Half or more of the artists that Advocates seek to speak on behalf of may be indifferent to the advocate’s call for changes in page rate formulas. Some may even actively oppose changes.

Suggested Advocacy Activities

- Form a Comic Artist Union. Unions have the ability to compel collective bargaining negotiations with specific employers through the National Labor Rights Act (NLRA) and as 501 (c) 5 organizations may freely engage in lobbying, potentially winning legislative battles that will empower artists. Unions can not take donations and so are largely funded by initiation fees and membership dues.

- Form a Comic Artist Guild or Professional Association: Guilds different from unions in that they are an association of craftsmen formed for mutual aid. While guilds may engage in collective bargaining, they do not necessarily enjoy the same privileges to compel bargaining under the NLRA as a union would. Guilds must instead organize protests such as boycotts. Guilds can be formed as 501 (c) 3 organizations, opening up options for funding and supporting programming, trading that flexibility for limits on lobbying efforts.

- Journalism: Exposés and opinion columns.

- Protests: Letter writing and boycott campaigns.

Service Innovators:

The ingrained nature of page rates and the experimental essence of innovation make it difficult to achieve living wage page rates through innovative services. A true Innovator would come up with a different, more equitable, way to pay artists, which is a tall order. It is better to use innovation as a method for incentivizing living wage page rates through non-typical programs and markets. Being agents of change, Innovators face many of the same issues as Advocates with artist values: A high degree of interest in community, empowerment, inclusivity, and transparency with constraints based on a lesser desire in the community for transformation. Additionally, Innovators suffer constraints in terms of what artists desire for services. Innovations will tend to come from services that mitigate participation costs and open up new markets for comic artists; however, these two services are among the lower desired services by surveyed artists: 57.32% for mitigating participation fees and only 40.59% for creating new sellers. Additionally, such services can be seen as benefiting other stakeholders (retailers, publishers, et. al.) as much or more than the artists, causing tension with artists who feel unempowered, disenfranchised, or otherwise left out.

Suggested Innovative Services:

- Microloans to small press publishers: A loan program that would allow small presses to pay artists a living wage page rate as long as the person in charge of the press has a business plan for the comic, possibly including crowdfunding, AND a full-time job as back up. This wouldn’t completely relieve publishers of paying the full living wage page rates, but it would serve to mitigate the barrier of price by allowing payments over time. Small press is an almost microscopic part of the comic book industry, but if these small efforts could generate the same or better page rates as mainstream publishers, it would put pressure on the industry as a whole to make changes. Microloans would have the advantage of returning funds so that a single donation could be used to fund multiple projects.

- Advertising match for sales of comics that prove they have paid a living wage page rate. 62.76% of comic artists surveyed indicated that they were interested in services that informed buyers of their projects, so an ad match program would likely be welcomed by the creators as well as provide incentive for publishers.

Service providers:

Like Service Innovators, standard Service Providers are best suited to programs that improve the conditions of individuals affected by non-living wage page rates as opposed to addressing the underlying problem itself. There are certainly already existing programs, initiatives, and institutions that do this. The question when applying a more standard service to the problem becomes one of negative spillovers. A fair question from the 68.75% of surveyed artists concerned with NPOs expressing values of equitability would be, “Do programs that supplement an artist’s financial health also, by default, prop up the system that pays non-living wages?”

Suggested services:

- More comic arts conventions, festivals, and fairs: For many years comic shows have been an additional source of income for comic artists

- Grants: For many years the Xeric Foundation grants were an important part of the independent comics culture They are less common now, but still existent.

Supplement with grants for paying a living wage. - Business Training is a service that is more or less a conventional one (i.e. not innovative in use or intent) and desired by 61.92% of artists surveyed. Classes on contract negotiation would empower artists’ ability to ask for a living wage page rate.

Conclusion:

The problem of instituting a living wage page rate in the comics industry is easy to articulate in general terms, but hard to frame in a manner that generates solutions. Based on social status, different artists have different minimum needs making a set living wage hard to peg. Adding even more complexity, many artists may be content taking lower than living wage page rates because they have additional employment or receive personal utility for simply being a contributor to one of their favored cultural institutions.

NPOs are perfectly suited to navigating complex issues like living wage, mostly because they are not beholden to making a profit like the market sector. Value Guardian and Advocate type NPOs can use their influence and non-profit status to address the difficulties of digging deep into problem framing by empowering and growing the comic artist community. Service Innovators can use non-conventional market interventions to incentivize publishers to instate living wage age rates. Service providers can (and do) operate in ways that supplement Comic Artist pay.

In any case, the first step in solving an issue as thorny as living wage page rates starts with research. Research can answer the questions of who is affected, to what extent, and, perhaps most importantly, what they would like to see done about it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply