Introduction to Part One of the 2020 Comics Arts Stakeholder Survey:

In May of this year, SOLRAD published the results of a Comics Arts Stakeholder Survey survey that I conducted with vendors at my annual Indie Comics Fair in Columbus, Ohio. Thanks again to the 14 vendors who helped me break the ice in a conversation about the comic artist identity and the relationship between comic artists and nonprofit organizations (NPOs) that exist in their community. As with all icebreakers, the intent of the first survey to find an entry point on a much longer and broader exchange. This second study is a stakeholder analysis of comic artists, meant to provide information to all parties in the comic arts community which will facilitate quality conversation.

For purposes of publication on SOLRAD, the results are being broken into two pieces: This first essay on Comic Artist Identity and a second part on Comic Artist Expectations of the NPOs that exist within their community.

Methods and Engagement:

This study used two separate surveys to gather information. The first survey was conducted with comic artists and received 240 responses. The second survey was with non-artists, asking them to estimate the responses of the artists in the first survey. The second survey had 49 respondents. The first survey was meant to be a tool for gathering actual information about aspects of the comic artist identity and the second survey was a tool for roughly demonstrating that there are cultural stereotypes about comic artists that can potentially bias the actions of individuals and groups who seek to address the problems of the comic arts community.

Both surveys are also tools for measuring a willingness of community members to engage in civics participation on behalf of the comic arts community. Initial respondents to the artist survey were recruited from my email, Facebook, and Twitter contact lists. Additional respondents were recruited through social media posts by other individuals and groups. The method of recruitment lends itself non-random sampling errors such as undercoverage due to voluntary response error and convenience sampling error. These errors open up the possibility of biased results, and so there should be a level of caution in applying the results to the comic artist population as a whole. One respondent indicated that results seemed biased towards the small press crowd, which is a possibility given the nature of my contacts. Based on the results of another study of comic artists, it is also apparent that the response rate of individuals who identify as belonging to a group that experiences bias and discrimination is low. Both sources of possible under coverage are acknowledged and discussed below in the sections titled “The Professional to Hobbyist Spectrum” and “The Undeniable Impact of Discrimination and Bias.”

For what it’s worth, some sort of nonrandom sampling error is likely in any given survey of comic artists because no work has been done to establish the dimensions of the population. No one knows how many people currently consider themselves comic artists, the rate at which that population is growing, or the rate of attrition is from the comic artist community. If I were to choose a single research project that would benefit all artists and those seeking to improve the comic arts community, it would be a comprehensive census study.

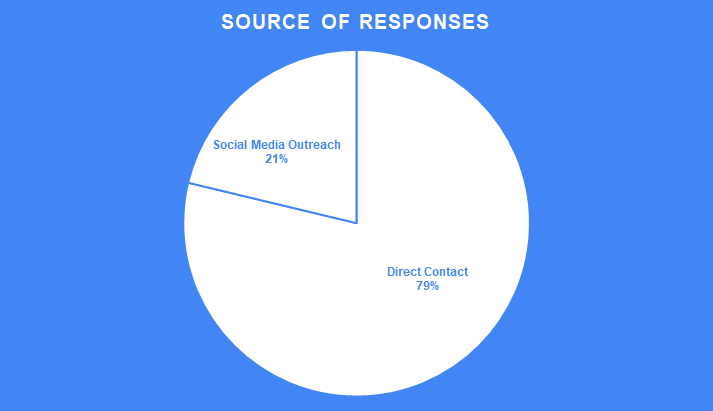

Three methods of recruitment were used in this survey with the following response rates:

- 79 responses from 154 emails sent (51.30% Response Rate)

- 65 responses from 120 Facebook messenger DMs (54.17% Response Rate)

- 45 responses from Twitter DMs (40.00% Response Rate)

Interest in further engagement is also high. Roughly, 87% of respondents indicated that they were interested in being sent the results of the survey and that they are willing to be contacted by email for further research.

Results: Part One

Stakeholder Analysis:

This study is modeled on John M. Bryson’s three steps of stakeholder analysis in “Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement” Those three steps are: to identify stakeholders; specify the stakeholders’ criteria for an assessment of an organization’s work; and to make a judgment on how well an organization performs against those criteria.

In this case, part one of the 2020 Artist Survey identifying stakeholders consists mainly of digging down on the notion of “Comic Artist” as an identity and establishing subcategories of that identity. Non-artists are also identified as stakeholders and are separately surveyed to illustrate potential cultural stereotypes at play in the comic arts community. NPOs are identified as a single stakeholder with the acknowledgment that within that identity there is an array of different identities based on the organization’s size, mission, and other factors. NPOs and non-artist stakeholders deserve and require further research.

Part two of the 2020 Artist Survey serves to specify what comic artist and subcategory identities see as their needs to reach their artistic aspirations (professional or personal) and what actions they want NPOs to take on their behalf. These are the criteria by which Comic Artists will assess NPOs in their community. Note: NPOs, in general, are used as the “organization” in Bryson’s model, but again with the acknowledgment that NPOs vary significantly in resources and mission.

Part of the 2020 Artist Survey and a second survey of “Second Party” or non-artist stakeholders are used to prepare artists and NPOs alike for a conversation about artist needs and NPO outcomes. It is meant to provide comic artists with advice on expectations, as well as effective language to voice those expectations. It is also meant to provide NPOs guidance on obtaining positive outcomes and feedback from comic artists as stakeholders.

Comic Artist Stakeholder Identity:

A typical way of dividing up the comic artist stakeholder identity is by the artist’s location in the marketplace. For instance, it is common to think of comic artists in terms of “Graphic Novelists” who generally create longer-form comics distributed by conventional booksellers, “Comic Book Artists” who often create shorter monthly publications distributed through the direct market (meaning direct to comic shops for the uninitiated), and “Small Press” artists who create across a full range of formats but are not affiliated with either of the two major forms of distribution. The problem with this model is that it only describes artists in terms of their stakes in the marketplace and not within the broader context of being an artist.

A purely marketplace based identity model of comic artists as stakeholders ignores the many individual artists who gain personal utility outside of the marketplace for their work. Illustrating this point, in Sasha Basset’s 2019 Comics Workforce Study, a majority of comic artists consider themselves comics fans and that making comics for a living is a “dream job.” The workforce study also shows “Opportunities for Creative Fulfillment” as a source of workplace concern for artists on par with “Pay” and “Work/Life Balance.” This presents the need for stakeholder categories that allow for more or less involvement with market-based identifiers. More simply put, buying and selling artwork is not the only issue involved in creating positive social change for comic artists.

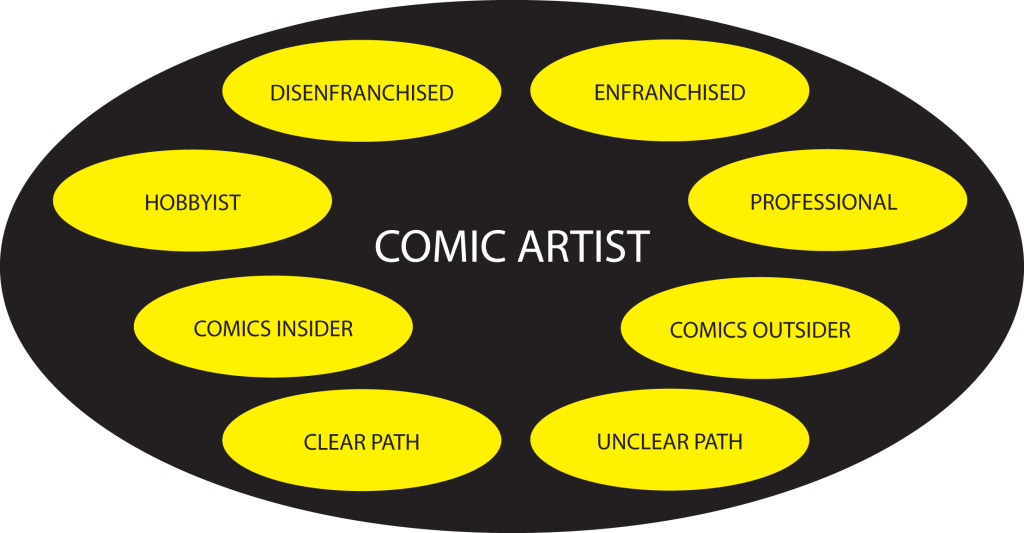

For purposes of this survey the following stakeholder identities are used:

Comic Artist: The umbrella stakeholder identity for all respondents of the survey. All other stakeholder identities listed are subcategories of comic artist. Those subcategories are mutually exclusive to one another; individual respondents are all members of multiple subcategories.

Disenfranchised: Respondents who answered yes to the question about belonging to a group that is the victim of discrimination and bias.

Enfranchised: Respondents who answered no to the question of discrimination and bias.

Hobbyist*: Respondents who did not report gaining any income from comic arts (Freelance, Royalties, Conventions/Fairs, or On-Line Sales of Art)

Professional*: Respondents who did not report having a Full-time Job, Part-Time Job, or living on Savings/Pensions

*It should be noted that the use of the terms “professional” and “hobbyist” are for lack of a better binary set of terms and not as a reflection of quantity or quality of work.

Comics Insider: Respondents who answered yes to having a comics-related day job.

Comics Outsider: Respondents who answered no to having a comics-related day job.

Clear Path: Respondents who answered yes to seeing a clear path to their artistic aspirations.

Unclear Path: Respondents who answered no to the path to aspirations question.

Second Party Stakeholders: Non-artist respondents to the Phase 3 survey.

Comic Arts NPOs: Nonprofit organizations whose mission statement specifically addresses the comic arts community. For the sake of limiting the word count, all mentions of NPOs in this study will refer specifically to Comic Arts NPOs.

The Professional to Hobbyist Spectrum:

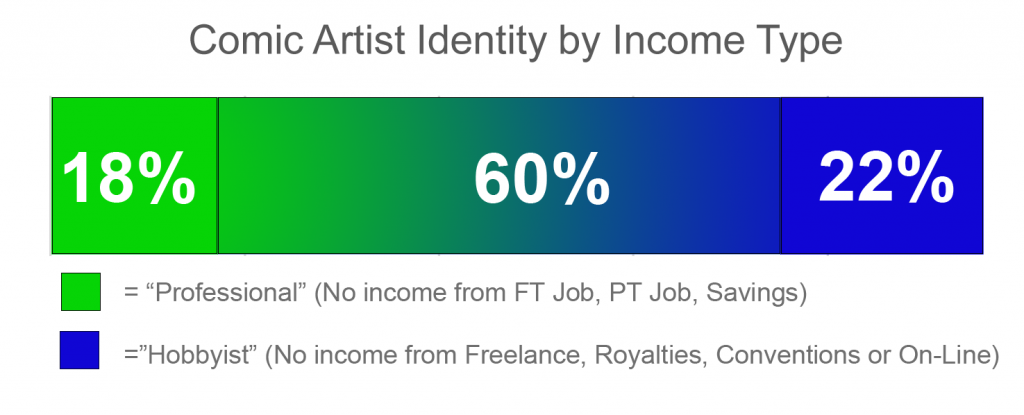

When broken down in terms of sources of income, the survey results indicate a fairly high rate of engagement with “professional” artists, described in this context as artists who do not receive income from a full-time job, part-time job, or savings/pensions. There is also a high rate of engagement with “Hobbyists,” defined as individuals who do not report any of the common comic arts-based sources of income: Freelance Work, Royalties, conventions/festivals, or online sales. The majority of respondents, however, exist on the spectrum between the two extremes.

In terms of Income sources, the “Professional” and “Hobbyist” groups differ considerably from the overall group of respondents:

| Source | Overall | Professional | Hobbyist |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part-Time Job | 22.08% | N/A | 7.69% |

| Full-Time Job | 52.92% | N/A | 91.67% |

| Savings | 17.08% | N/A | 7.69% |

| Freelance Work | 66.45% | 95.35% | N/A |

| Royalties | 22.08% | 46.51% | N/A |

| Online Sales | 41.25% | 53.49% | N/A |

| Fairs/Festivals | 45.00% | 51.16% | N/A |

| Student Loans | 1.67% | 2.33% | 0% |

The Professional income stream is marked by a dominant increase in the amount of freelance work used, a greater rate of converting those freelance works into ongoing royalty payments, and an increase in the use of On-Line sales and Conventions, fairs, and festivals. Professional respondents have an average career length of 18 years, work on average 25 to 37 hours per week on comics, and are about 8.5% more likely to see a clear path to their aspirations than the overall group of respondents.

The Hobbyists are nearly all employed full time. Hobbyist respondents have an average career length of 12 years, work on average 10-14 hours per week on comics, are 19% less likely to have a comics-related day job, and are about 11% less likely to see a clear path to their aspirations than the overall group of respondents.

These income source differences alone merit defining Professional and Hobbyist as subset stakeholders of a “Comic Artist” identity. There are additional differences in the section on the Artist relationship with NPOs that further establish the distinction.

Individual Question Responses

Individual survey questions will be analyzed based on the responses of the entire group of individuals who took the survey (Overall respondents), responses when broken down by the constituent comic artist identity subcategories (Professional, Hobbyist, Enfranchised, Disenfranchised, Comics Insider, Comics Outsider, Clear Path, and Unclear Path, as described above), and the estimations of Second Party stakeholders in the Phase Three Survey. Stakeholder Group response differences are considered notable if they differ by 5% or more from the Overall Respondents’ response. Second Party responses are considered to show a cultural bias if 40% or more of those respondents estimate higher or lower than the actual Overall Comic Artist response.

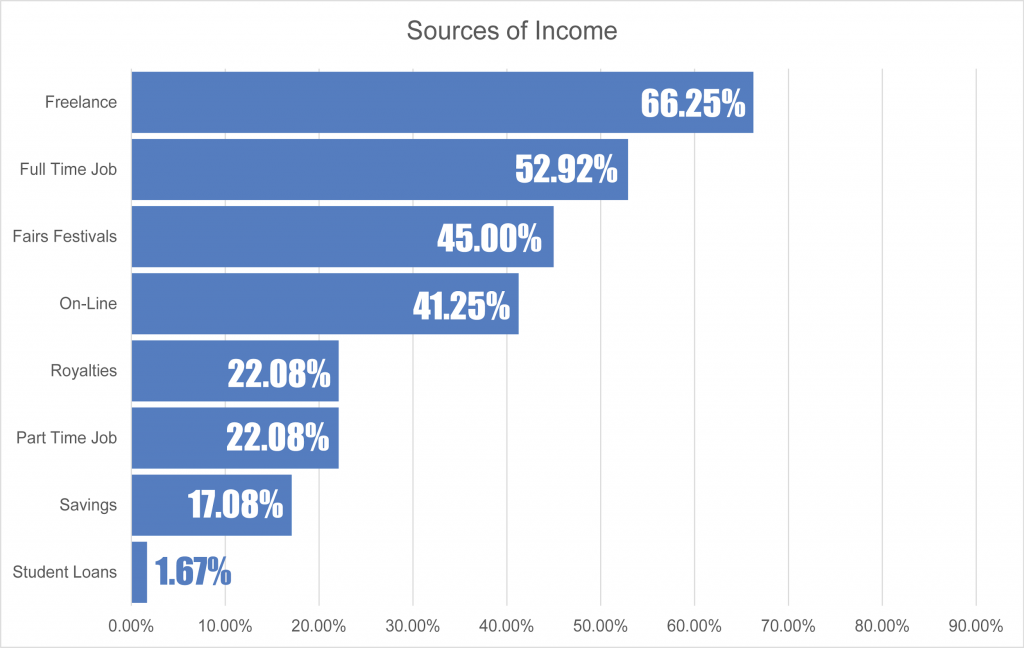

Sources of income: The goal of this question was to establish the comic artist identity in terms of financial, time, and skill resources available to the responding artists.

As a personal reflection on methodology, this question desperately needed an “other” option. Two different respondents let me know subsequent to taking the survey that they felt the survey omitted major parts of their income. Film rights for one, freelance work and crowdfunding that was comics-related but not actual art creation for another. From personal experience, I know that grants and awards can also contribute to an income stream. I don’t think that any of these specific omissions would be majority categories, likely occurring on a level somewhere in between “student loans” and “savings,” but it is an element of the community that I have carelessly erased.

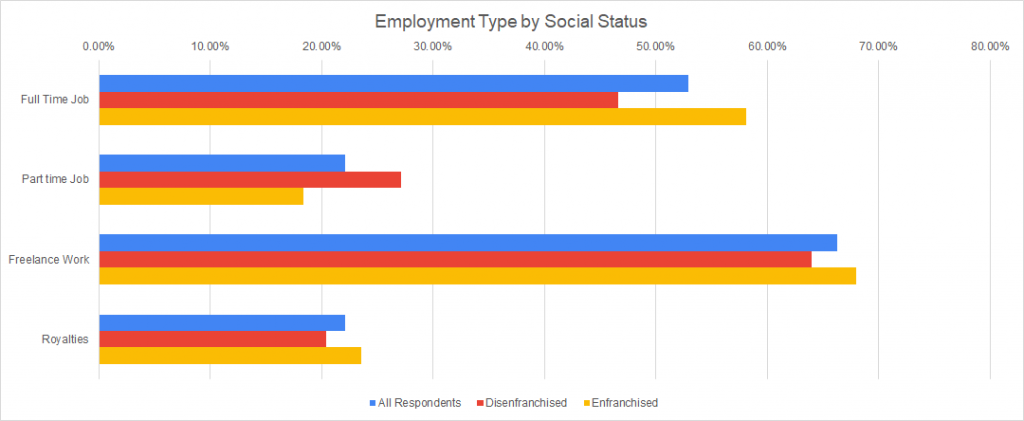

Freelance Work: Freelance is the only source of income universally reported by the majority of respondents. This is consistent across most subsets of the comic artist Identity, with the only exception being Hobbyists.

Second Party stakeholders do not have a strong sense of the amount of freelance work that artists take on, with 46% underestimating and 31% overestimating the number of artists who use freelance work as a source of income.

This prevalence of freelance work, with a predominance towards work-for-hire arrangements based on the low rate of respondents who receive royalty payments, has implications for NPOs in that they should acknowledge and address the pitfalls faced by a community of gig economy workers, including a lack of consistent pay and a lack of access to social services.

Full-Time Job: The overall majority of respondents (approximately 53%) reported having a full-time job. This is roughly equivalent to the employment to population ratio listed at the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the same period of time as the survey was conducted.

As divisions are made into other subcategories of the comic artist identity, the rate of full-time changes. Hobbyists almost universally work a full-time job. Disenfranchised respondents are about 6% less likely to have a full-time job than the group as a whole. Respondents reporting artistic careers in the top quartile of length (19 years or more) only have full-time jobs 38.8% of the time, working more hours on comics and relying on a greater rate of freelance work for income. Respondents who do not see a clear path to their artistic aspirations are 6.62% more likely to have a full-time job than those who do see a clear path. 63.64% of full-time respondents do not report having comics-related day jobs. 46% of Second Party stakeholders underestimated the rate of full-time employment of comic artists.

An implication of this high rate of full-time employment for artists is that the need for financial and social stability often outweighs the desire for artistic productivity. For NPOs, the rate of full-time employment is valuable for weighing the potential for respondents’ contribution of social capital and resources. On the positive side, respondents to the artist survey are perhaps more likely to be able to contribute monetarily in the form of donations, paying for services, and/or paying dues to a planned professional association than expected. Additionally, artists with employment history outside of the comic arts may have valuable skills and experiences that they can bring to volunteer efforts. On the downside, the large number of comic artists with full-time jobs may indicate less time to participate in NPO activities as either program beneficiaries or volunteers. Also on the downside, the relatively high rate of full-time employment among respondents may indicate that participation in the comic arts as an artist is a privilege that is more accessible to more affluent individuals.

Part-Time Job: Less than a quarter of overall respondents reported holding a part-time job. The majority of these part-timers live in the realm between the Professional and Hobbyist stakeholder subgroups, with hobbyists having a part-time job 7.69% of the time and professionals, by definition, not having any part-time jobs. Disenfranchised artists, artists who do not see a clear path to their artistic aspirations, and respondents with comic-related day jobs all have part-time jobs roughly 27% of the time. Second Party stakeholders overestimated how many respondents would have a part-time job 90% of the time (!!!). The part-time rate of employment stands in contrast to the cultural stereotype that comic artists work full-time on comics and hold down a part-time job. The implications for NPOs regarding part-time employed artists are similar to the implications regarding full-time employment in that there may not be as many artists in the community able to volunteer time or skills as hoped for. Notable for NPOs, especially those that value empowerment and community, is the higher rate of part-time comic-related work, as NPOs are able to directly impact these rates themselves, either by helping to create more part-time comics-related jobs for artists and/or building existing part-time positions into full-time positions.

Royalties: Less than a quarter of respondents receive income through royalties. Professional respondents more than double that rate, with 46.51% earning royalties. Respondents who see a clear path to their aspirations are about 10% more likely to be earning royalties (32.77%). Respondents who do not work a comic-related day job only earn royalties 15.45% of the time. The majority (71%) of Second Party stakeholders have a generally good assessment of the artist royalties situation. For artists who aspire towards the professional end of the stakeholder spectrum, these numbers imply that taking the time to find work that pays ongoing dividends and/or is at least peripherally engaged with the comic arts community may lead to additional stability. For NPOs, professional development activities that aid in accessing and creating opportunities that generate royalties is an area that would be useful to artists.

Online sales: At 41.25%, online sales are a frequent source of income for respondents, but not a majority. This approximate rate is fairly consistent with most stakeholder subgroups, with response rates falling within 3.5% above or below the overall score. Professional respondents use online sales 53.49% of the time. Respondents who do not have a comics-related day job only report online sales as a source of income 35.45% of the time. 40% of Second Party stakeholders overestimate the number of artists who earn income online. Artists and NPOs should consider this area a somewhat unexplored frontier, examining to what extent the professional respondents have a greater rate of online sales due to a superior market position or whether the additional use of online venues helped carry them to that superior position. Similarly, it should be examined whether comics-related day jobs are a source of access or if there are accessibility barriers for those not as tightly knit into the comics community.

Conventions and Festivals: At 45% overall,cons, fairs, and festivals as a source of income is similar to online sales in that it is fairly consistent across multiple stakeholder subgroups with some notable exceptions. Professional respondents use conventions as a source of income 51.16% of the time. Respondents who see a clear path to their artistic aspirations sell at these venues 51.26% of the time, but those who do not see a clear path do so only 38.84% of the time. Those without a comics-related day job only use conventions 40% of the time. Second Party stakeholders overestimate the number of artists who vend at events 47% of the time. Conventions are notoriously hard to consistently earn income at, thanks to the inherent transaction fees such as table rental and travel expenses. This implies for both artists and NPOs that the value of cons and fests lies in access to the comic arts community rather than simple market success.

Student Loans: As a personal reflection, the inclusion of this category may have come from a personal bias resulting from my personal connection with many current art and former art students. It became apparent as survey participants were recruited that the number of respondents who are currently students would be negligible. Certainly, Comic Artists currently paying student loans will face the additional barrier of debt to a successful career in the future, but it’s unclear how many face that issue. The majority (57%) of Second Party Stakeholders understood that the number of artists living on student loans would be low.

Non-Income Related Comic Artist Identity Aspects

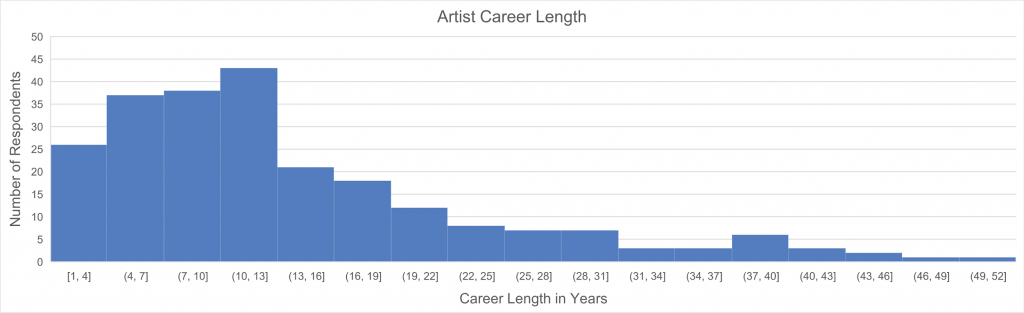

What exactly constituted the beginning of a respondent’s career was left intentionally vague to encourage participation by individuals who may not view their life as a cartoonist in purely professional terms. This question measures the career length only in terms of the longest possible length. It does not measure when a career may have ended in the respondent’s mind (call me a hopeless romantic, but I don’t think a comic artist career is over until they are either physically unable to continue or so broken-hearted that they will not acknowledge the past).

Median career lengths are given as statistical outliers and inflate the average by as much as 3 years.

| Stakeholder Type | Average | Median |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 14 years | 12 years |

| Professional | 21 years | 18 years |

| Hobbyist | 12 years | 11 years |

| Enfranchised | 16 years | 13 years |

| Disenfranchised | 12 years | 9 years |

| Sees a clear path to aspirations | 16 years | 13 years |

| Does not see a clear path to aspirations | 13 years | 11 years |

| Comics-related day job | 15 years | 13 years |

| Day job is not comics-related | 12 years | 11 years |

A good number (37%) of Second Party stakeholders guessed between 10 and 15 years of experience would be average for respondents, without a bias towards the inaccurate responses being high or low.

The top quartile of career length respondents reported careers of 19 years or longer. These veteran respondents rely on Freelance Work at a rate of 77.97%, over 11% greater than the overall group. Taken with the 95.35% of Professional respondents who rely on freelance work, this suggests that long careers are dependent on consistent access to freelance opportunities over an extended period of time. It also implies that older artists have more at stake when dealing with the issues created by freelance work in terms of income, healthcare coverage, housing, et al.

Disenfranchised respondents report shorter careers than their enfranchised counterparts. The top quartile of career length respondents includes only 22.03% disenfranchised respondents, indicating that, historically, disenfranchised stakeholders have not had the same opportunities as their counterparts, or they have faced greater barriers to an extended career. Improvements in inclusivity over the past decade or so, though, has allowed better opportunities for the disenfranchised respondents.

Hours Worked: Respondents were asked to provide either a set number of hours (for example 30) or a range of hours (for example 10-15). As the field was an open answer opportunity, many respondents (14%) took the opportunity to express that this was a difficult question to answer as outside factors such as availability of work, conflict with other work, confounding artistic ventures, and the stage of a given project cause serious variation from week to week.

| Stakeholder Type | Avg Hrs/Week |

|---|---|

| Overall | 14-21 hours |

| Professional | 25-37 hours |

| Hobbyist | 10-14 hours |

| Enfranchised | 13-20 hours |

| Disenfranchised | 15-23 hours |

| Sees a clear path to aspirations | 18-25 hours |

| Does not see a clear path to aspirations | 10-17 hours |

| Comics-related day job | 14-21 hours |

| Day job is not comics-related | 12-19 hours |

51% percent of Second Party stakeholders overestimated how many hours respondents work per week. Combined this with the 90% of Second Party respondents overestimating the number of respondents with part-time jobs indicates a misleading cultural stereotype of the comic artist identity.

The striking difference between respondents who see a path to their artistic aspirations and those who do not would be a good area for further research. Does the ability to see that path enable artists to work more hours or does the act of working more hours lead to a clarity of vision? What can artists and NPOs alike do to bring clarity to the paths of artists who do not see a way forward?

Comics-related Day Job: It is a reasonable premise that working within the comic arts marketplace can lead to a more successful career as a comic artist. This question was included in the survey to test that premise. In the original Indie Comics Fair survey, this dramatically manifested in a distinct split where the respondents with comics-related day jobs all were able to work more hours on average than those without comics-related jobs. That is not true of respondents in this project, although there is clearly a general advantage (14-21 hours versus 12-19). A larger advantage is apparent in the ability of respondents to access freelance work, with 72.88% of comics-related job respondents reporting freelance work compared to only 56.36% of non-comics-related job respondents. Non-comics-related job respondents are less likely to use online sales and conventions as a source of income. Comics-related jobs do seem to skew more towards part-time employment and non-comics-related job respondents tend to have greater rates of full-time employment.

At 51.75%, a slight majority of overall respondents have comics-related day jobs. This slight majority holds true for professional stakeholders, both disenfranchised and enfranchised stakeholder subgroups, and respondents who see a clear path to their artistic aspirations. Only 47.11% of the respondents who do not see a clear path to their aspirations and 32.70% of hobbyist stakeholders have comics-related day jobs. Second Party stakeholders, as a whole, dramatically underestimate the number of respondents who have comics-related day jobs.

Clear Path to Aspirations: Similar to the question of career length, the definition of aspirations is left up to the respondent. This is to capture the measurement of satisfaction among respondents independent of financial success. Level of satisfaction is important when examining artist’s response to issues they face within the community in terms of exit, voice, and loyalty. Artists who are less satisfied are likely to have less loyalty to the community and exit (i.e. quit comics) when presented with barriers or inequities. Artists who see a clear path are more likely to exercise their voice and engage with their community when presented with problems due to greater loyalty. Unfortunately, the higher degree of loyalty also leads to a greater potential for exploitation. For example, an artist who feels that working in comics is a “dream job” is less likely to use their voice to express disapproval or to exit the field.

A slight minority (49.58%) of respondents see a clear path to their artistic aspirations. This is consistent among Enfranchised, Disenfranchised, and Comics Insiders and Comics Outsiders. Comics Insiders don’t show a notable difference by a standard of 5% difference, but they do see a clear path the majority of the time (51.69%). Professional respondents in the majority (58.14%) see a clear path to their aspirations. Hobbyists (38.46%) have a notably lower rate of seeing a clear path.

Second Party survey respondents showed a significant bias towards underestimating the number of respondents who would see a clear path to their artistic aspirations.

Discrimination and Bias: The overall group of respondents reports belonging to a group that currently and/or historically experiences bias (41.30%). This rate is consistent between all stakeholder categories, but there is a notable difference when viewed in terms of the top quartile of career length, where only 22.03% of respondents report being disenfranchised.

The Undeniable Impact of Discrimination and Bias

The relative lack of respondents who identify as belonging to a group that suffers from bias and discrimination needs to be addressed first and foremost before diving into the overall results. 43.10% is likely a low result due to under coverage, a result of a heavy reliance on my personal network. Sasha Bassett’s 2019 Comics Workforce Study reports that only about 40% of comic artists identify as men, 30% of those men are likely to be of a non-white race or ethnicity, and 56% are likely to not identify as heterosexual. That would indicate a potential true population census around 88% comic artists identifying as a group that experiences bias. The truth is likely somewhere in the middle. This would not be a big deal if the two groups, enfranchised and disenfranchised, had similar responses to survey questions. They didn’t, as should be expected when discussing bias and discrimination. For the sake of simplicity, I am referring to the individuals who do not belong to a group that experiences discrimination as “Enfranchised” and Individuals who do experience bias as “Disenfranchised.” Use of the terms Enfranchised and Disenfranchised meant to be both reflective the social status of the respondent groups and as a mea culpa for myself. I needed to work harder to engage with those disenfranchised voices.

Sources of Income: The majority (52.92%) of all respondents reported having full-time jobs, but there is a significant gap between the enfranchised and disenfranchised respondents, with only 46.60% of the disenfranchised group having full-time jobs to the enfranchised 58.09%. The disenfranchised respondents were 8.80% more likely to rely on part-time work than their enfranchised counterparts. Disenfranchised respondents are moderately more likely to earn income through freelance work and slightly less likely to receive royalties. The difference becomes more striking when comparing the gap between freelance work and royalties; a gap representative of the difference between the “gig work” and ongoing income. The gap for disenfranchised respondents is 47.57% (67.96% freelance work and 20.39% royalties) versus only 40.44% (63.7% minus 23.53%) for enfranchised respondents.

Hours Worked: Disenfranchised respondents report working on comics at a slightly higher average per week. 15 to 23 hours versus 13 to 20 for enfranchised respondents. This may be due in part to the slightly higher use of freelance work as a source of income and a higher tendency to have part-time work over full-time work.

Career Length: Disenfranchised respondents had shorter careers on average, 12 years compared to 16 years for enfranchised respondents. While on the surface this would appear a negative, it actually, in many ways, is reflective of the comic arts expanding in diversity. This becomes evident when looking at the top quartile of respondents in terms of career length. Those respondents overwhelmingly fell into the enfranchised category, with only 22.03% reporting being disenfranchised. Better isn’t the same as good… but things are better!

Aspirations and Comic Related Day Jobs: Both disenfranchised and enfranchised respondents report very similar rates of seeing a path to their artistic aspirations and rates of having comics-related day jobs.

Part One Conclusions:

- Comic Artist research is hampered by the lack of information on the population as a whole. Not knowing any information on the population makes non-random sampling errors such as under coverage impossible to avoid. A census of the comic artist population could be used to address this issue. The results of this comic artist survey can not be considered as representative of the population as a whole, but they can be seen as indicative of trends among identity groups.

- The Comic Artist identity exists on a spectrum between Professionals who derive all of their income from the Comic Arts and Hobbyists who derive no income from the Comic Arts. In this study, 18% of the respondents were Professionals, 22% were Hobbyists and 60% (the majority) of respondents live on a spectrum in between.

- Based on Sasha Basset’s 2019 Comic Workforce Study, it is likely that individuals who experience discrimination and bias are underrepresented in the artist survey respondents. When the enfranchised and disenfranchised groups are broken out and examined separately, the effects of this under-coverage can be seen.

What to Look for in Part Two:

Part two of this essay will review the Comic Artist relationship with nonprofit organizations (NPOs) in terms of respondent’s stated desire for specific NPO activities, the way in which they desire NPOs to function within their community, and the values that they expect NPOs subscribe to as members of the community. Part two will also review the Second Party survey and examine bias created by cultural stereotypes of the Comic Artist identity.

The second part of this survey analysis and discussion will be published on 8/11/2020.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply