The close of 2021 takes with it the 500-year anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlan and its sister city Tlatelolco, the Mexica (meh-shee-cah) capital of the Triple Alliance—or what many may be more familiar calling “The Aztec Empire” (read about why “Aztec” itself is a misnomer here). On August 13, 1521, after a 93-day siege, Cuauhtémoc surrendered to Spanish forces that were heavily aided by foreign disease and domestic allies, namely the Tlaxcala, who knew a power vacuum when they saw it.

Regarded as “the Venice of the New World,” Tenochtitlan had many amenities associated with any contemporary sixteenth-century city. From sports arenas and civic centers to libraries, arboretums, steam rooms, and zoos, the denizens of Tenochtitlan enjoyed a vibrant cosmopolitan lifestyle. Additionally, aqueducts and complex sanitation systems kept the metropolis cleaner and healthier than most contemporaneous European cities. This is to say nothing of it being a nexus for wealth and trade across the Alliance. The loss of Tenochtitlan was devastating not only in the loss of human life and culture but also in the precedence it would set for European exploitation and genocide of indigenous peoples in the Americas.

While the quincentennial of the fall of Tenochtitlan and its associated empire is not insignificant, I balked at connecting it to an essay about the representation of Mesoamerica in comics. Having grown up seeing the Americas framed almost exclusively in the context of so-called “First Contact” or colonialism (animated features such as Disney’s Pocahontas and DreamWorks’ The Road to El Dorado come to mind), I did not want to perpetuate talking about my indigenous ancestors with the beginning of their trauma. The lives and existence of Native peoples are so much more than their relationship to European history.

That said, there is still a significant reason for this essay this year: namely, 2021 was a phenomenal year for the representation of Mesoamerica in popular media!

From the kick-down-the-doors Netflix animated series Maya and the Three to the futuristic video game Aztech: Forgotten Gods, Mesoamerica is finally getting its due. While Mexico has been portrayed in U.S. comics at least as early as 1935 (New Fun Comics Vol. 1, #1) and “Aztec” characters have been present for no less than the past 75 years (referenced in Golden Lad Vol. 1, #1, in 1945 and featured in Rawhide Kid Vol. 1, #51, 1966), up until recently, Mesoamerica was not depicted by Latinx writers or creatives. Rather our stories were often told by white folks who exotified, caricatured, and otherwise marginalized the various cultures in these portrayals. Now after literal centuries of fighting to tell our cultural narratives, Latinx storytellers are able to shed light on an aspect of our heritage that is often overlooked and misrepresented.

Where We Were

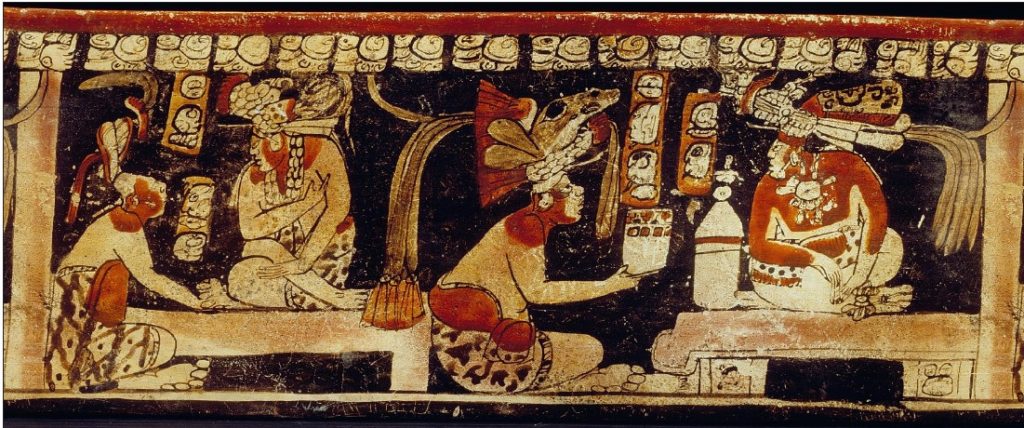

Illustration in human history is ancient, but illustrations that look like comics – now that’s something! One of the earliest pieces of art with motifs that could be described as “comic-like” are Mayan illustrations dating as far back as 650 B.C.E. In these pieces, speech is represented with wispy lines flowing from the mouth to wrap around glyphs – essentially, speech bubbles.

Over the centuries, sacred documents, called “codices” (singular: codex), would proliferate the government offices and libraries of other Mesoamerican societies, including the Maya, Mixteco, and the Triple Alliance. Typically in the format of a screen-fold or a scroll, writing in codices utilized both pictographs and glyphs. The city-state of Tenochtitlan alone is estimated to have had about fifteen libraries, covering subjects from poetry to philosophy to medicine. While there were easily upwards of a hundred of thousand of codices throughout the Triple Alliance and perhaps even just in Tenochtitlan, only about 16 pre-Hispanic texts survive to the present.

So, what happened to all these texts?

They were burned during the Spanish invasion. Elements of genocide, of course, are not limited strictly to human slaughter. Genocide also includes the destruction of the culture, knowledge, and narratives to advance the target society’s erasure.

Now, the Spanish would go on to commission new codices. Since the sixteenth century, 500 codices were produced under Spanish supervision, propagandizing religion (namely Christianity), a racial caste system that centered and elevated whiteness, and the notion that anything tied to indigenous ways was at best primitive or at worst, inhumanely savage. The most demonized and sensationalized of practices being the ritual of human sacrifice. The power of this propaganda would echo well into the twentieth century.

“Aztecs” and Comics

Early depictions of Mesoamerican peoples in U.S. comics include the Aztecs in an issue of Rawhide Kid trapping one of the protagonists (Rawhide Kid, Vol. 1, #51, 1966), Thor battling an Incan thunder god (Thor Annual, Vol. 1, #7, 1978), and Wonder Woman taking down Tezcatlipoca, god of chaos, in Wonder Woman #314 (1984). Superheroes such as the cringe-inducing El Dorado or the noble-but-briefly-featured Aztek make appearances inconsistently in animation and comics. More visible depictions since then have included Captain Mexica (2009) being revived as a zombie and ravaging A.R.M.O.R. agents and Hummingbird, who in Scarlet Spider Vol. 2, #17 (2013) reveals herself to be a host for the war god Huitzilopochtli and demands blood. The pattern is infuriatingly consistent. Even 450+ years later, the one-note representation of “Aztec” society is blood sacrifice.

Instead of being acknowledged as complex human societies, Mesoamerica is lumped in a MayaIncaTec sort of mish-mash, as if these were the only three (and relatively interchangeable) civilizations that existed across Central and South America. As seen in Hellboy vs. the Aztec Mummy (Dark Horse Presents #7, 2012), the rich and varied mythologies of Mesoamerican cultures are reduced to a Monster-of-the-Week, a speed bump thrown into the hero’s pathway that’s exotic enough to mix it up from the typical Western eldritch abomination but never noteworthy enough to take up more than an episode or two.

In addition to being portrayed as bloodthirsty or supplying a supernatural entity after human flesh, Mesoamerican peoples are often portrayed as being easily duped because, as anyone who has the popular (and inaccurate) narrative of “the Aztecs” knows, Hernando Cortés got a bunch of people to believe he was a god, so why wouldn’t it work again? And so, Eternals and mutants alike get mistaken for gods (Eternals Vol. 1, #2, 1976, X-Factor Vol. 1, #24, 1988, and Superboy Annual #3, 1996) and heroes like Rawhide Kid can hoodwink their captors with a simple disguise.

In reality, this myth of the conquest was fostered a solid 30 years after the fall of Tenochtitlan, first appearing from Cortés’ chaplain and secretary Francisco López de Gómara in 1552. As scholar Camila Townsend has noted in Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs, of course “conquistadors and their cultural heirs should prefer to dwell on the Indians’ adulation for them rather than on their pain, rage, or attempted military defense.” Essentially, it’s always easy to justify the systemic killing of people if they are depicted as morally and intellectually inferior.

And this is what white supremacy looks like.

White supremacy looks like being taught in school in that your ancestors had it coming, that their alleged conquest was inevitable, and the entertainment you consume reinforces that. White supremacy looks like having a totally separate set of vocabulary to refer to your ancestors as primitive (e.g. the Triple Alliance’s military was made up of “warriors” while Rome had “soldiers”). White supremacy looks like having all your fantasies reflect someone else’s because what remains of your inherited mythos is marginalized.

In an interview on the inspiration for his latest high-fantasy graphic novel, Helm Greycastle, Henry Barajas shared, “While I was playing [Dungeons and Dragons], I realized, ‘Oh, there are no Brown people here’.”

Bloodthirsty and bygone, Mesoamericans and, by extension, other Native peoples are often depicted as relics of the past and in such a way that they are seen as incompatible with our modern era.

Until, of course, their descendants do something about it.

So, how is Mesoamerica represented today?

Five hundred years of misrepresentation, misinformation, and outright missing knowledge is a lot to fix. But at least now, stories about and featuring Mesoamerica today are getting something that’s been missing for so, so long: care. Care means context and understanding. Onyx Equinox, a Crunchyroll original animated series by Mexican creator Sofia Alexander, didn’t shy away from depictions of human sacrifice, but it was pristinely clear as to why the invaluable cost of human life was necessary to stave off divine wrath. Audiences also saw the deliberate measures that were taken to prepare someone who had volunteered to offer their life to the gods. While violent, there wasn’t anything done for sheer bloodlust.

On that note, where are the Spanish? Mostly in the audience. Many contemporary stories on Mesoamerica have chosen not to focus on first-contact (or any contact for that matter) and the ones that do, present a history that is carefully researched to shift what has long been a one-sided narrative. Noticonquista, a project supported by UNAM and el Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, released five unique short comics this past summer 2021 memorializing the fall of Tenochtitlan through indigenous perspectives. In a massive undertaking to explore the years from 1519-1521, Paul Guinan’s online graphic novel series Aztec Empire illustrates in full color the emotions and livelihoods that were swept up in the invasion. Each chapter of Aztec Empire features detailed endnotes that cite both source material as well as provide further insight on historical events and even the selection of clothing or setting. The recently released series Aztec Warrior God reimagines a reality where Tenochtitlan survives Spanish invasion and builds a new future.

This past fall, the video game Mictlan dropped its play-through trailer depicting the fateful clash between Mexica jaguar knights and Spanish invaders. Viewers will be pleasantly surprised to hear dialogue that is in both Spanish and Nahuatl. The game’s predominantly Mexican and Mexican-American team also connected with indigenous community members and modeled the game characters’ faces after theirs. This is what care and intentionality look like.

Care, most importantly, breathes humanity into characters and prevents them from being a two-dimensional caricature of limited stereotypes. Louis Fogerty’s Rey Sol Tonatiuh gives us a Mexica pantheon that squabbles, that jokes, that has personality. Gonzalo Alvarez’ Piyoman: Warrior of the Sun, a graphic novel set to debut in 2022, features a young fainthearted protagonist from the present day who ventures into the Mexica underworld of Mictlan . . . dressed as a chicken. Macoatl, a running webcomic strip, by Ruy Fernando Estrada centers on restaurant life with fanciful characters that are sassy, silly, and humanly flawed for all their inhuman appearances. Superheroes such as Chronos, Koatl el Defensor, and Tonalli are prime examples of DCU and indie heroes that leap off the page because their creators invested in rounding out their narratives and histories. It’s with the proliferation of stories like these that we – creators, writers, and artists – are able to see and tell our stories in the way we’ve wanted to be seen.

Webcomics such as Codex Black, Ixpule, and Necahual take stylistic cues from manga and immerse readers in rich fantasy worlds. Codex Black by Camilo Moncada Lozano follows Mesoamerica’s cutest strongwoman, Donaji, as she searches for her father and is accompanied by a boy harboring a mysterious crow spirit. If Codex Black follows some standard shonen tropes, then Necahual captures the dazzle and delicacy of shojo without losing a drop of action.

“We originally wanted a magical girl series,” says writer Sergio Silva when he began collaborating with Necahual’s artist, Crystal Galloway. “Especially for colors and designs, we’ve been pretty happy with how it all turned out.”

Daniel Parada’s painstakingly researched and richly illustrated series Zotz focuses on warring Mesoamerican superpowers and the Mayan twin brothers caught between them. Parada shares, “I wanted to tell a story that had the epic scope I imagined, while also grounded on research and still entertaining for people familiar and unfamiliar with the cultures.”

This particular aspect of having stories that are available to audiences that are unfamiliar with Mesoamerica is also vital. Father/daughter-author/illustrator team David Bowles and Charlene Bowles bring to life a famous Mayan historical legend in the graphic novel The Rise of the Halfling King. Hatching from an egg, an alux (Mayan “faerie” more or less) boy grows up to challenge the wicked king of his locale. Stories from Mesoamerica are just as rich as anything to crawl out of the Grimm Brothers’ collection, but they just haven’t gotten the Disney treatment. With humor and heartfelt storytelling expressed through the characters’ rounded designs, The Rise of the Halfling King makes one of so many stories more accessible to younger audiences.

Perhaps the most visible trailblazer into mainstream audiences is Jorge Gutierrez’ animated series Maya and the Three (Netflix). Following a Mexica-Teotihuacan-inspired princess-warrior, Maya and the Three pays action-packed homage to some of the distinct cultures that comprise Mesoamerica. The series also recognizes aspects of modern-day Latin American culture that are rooted in indigenous practices. Día de los Muertos gets a lot of love now every November thanks to Disney’s Coco, but it’s Maya and the Three that underscores where this holiday originated. Reviews have pointed out the staggering body count that the series holds for a Y7 rating. But it’s with care, the show deals with death and sacrifice in such a way that feels both culturally specific and universal.

The list of comics, animated series, and video games mentioned is by no means exhaustive. However, this hopefully provides a glimpse into the wealth of existing content and the many stories yet to come from Mesoamerica’s heirs and our allies. After all, we’ve got 500 years of lost time to catch up on. That’s a whole lot of stories to tell.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply