Joshua Cotter’s Nod Away is stealthily one of the most ambitious comic projects currently being published. Projected to span several thousand pages across seven eventual volumes, it’s a massive sci-fi epic-in-progress. Two volumes have been published by Fantagraphics so far, the first in 2016 and the second in 2021, and Cotter is now working on the third. Although the two volumes to date are in some respects quite different from each other given the expanding scope of the saga, they are unified by a very human, emotional approach to sci-fi. Cotter mostly gestures obliquely at the heavy high-concept ideas introduced in Nod Away, revealing the technological and metaphysical underpinnings of this world organically through the lives and conversations of the characters.

This is a world that has been drastically altered by the invention of the “Innernet,” colloquially called “streaming” by its users. Individuals receive implants that connect them to a collective hive mind, through which they can mentally download all sorts of information and entertainment resources. Many choose to get connected, even though some people retreat so thoroughly into streaming that they become outwardly mindless, watching cartoons in their heads while responding with grunts to external stimuli from the real world. Anyone who’s read these kinds of stories before will suspect that there’s an ugly secret at the root of streaming, the nature of which is heavily hinted at from pretty early on. Digging into the details of that secret, and eventually exploring its origins in the second volume, is a major thrust of the work so far.

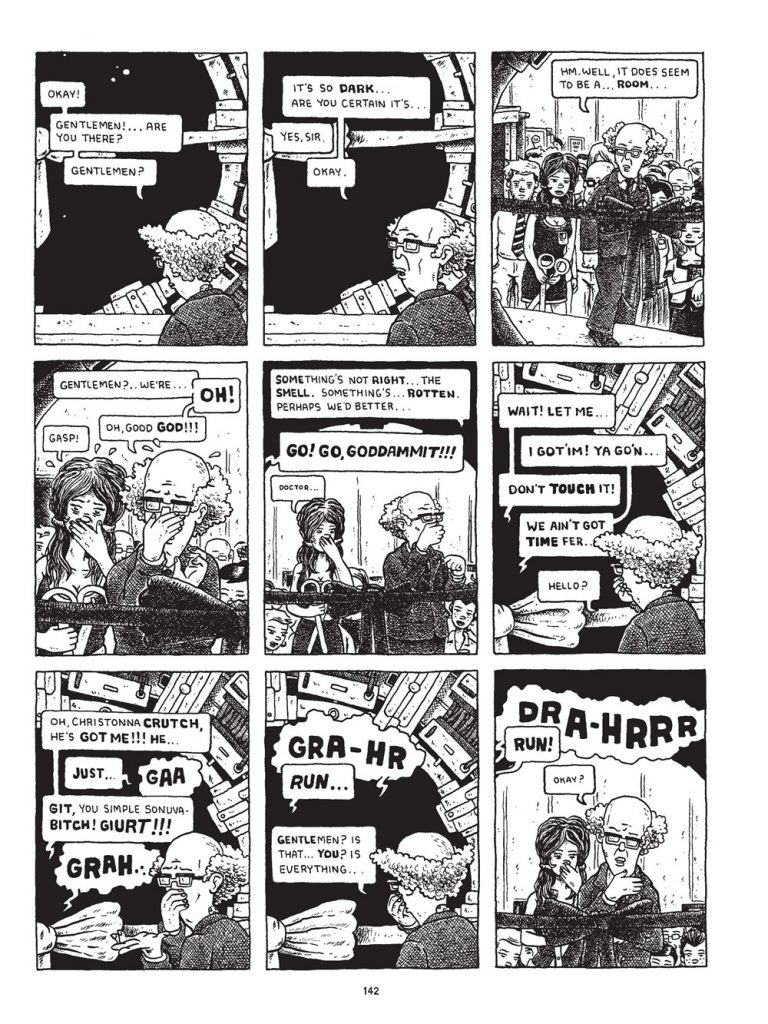

The first volume focuses on Dr. Melody McCabe, a neuroscientist reporting to work on the orbiting space station U.S.S. Integrity. Though Melody’s job occupies her elsewhere, the station is on the verge of testing a big breakthrough, a teleportation gate linking Integrity to another station. A mood of creeping dread lingers in the background leading up to this momentous event. Although much of the story proceeds as slice-of-life in a sci-fi setting, focusing on the characters and their mundane daily interactions, there’s always an unsettling ambiance, established in abstract interstitial segments and sinister foreshadowing, hanging over every casual conversation. In both volumes, Cotter meticulously builds a world that feels real and lived-in, a solid foundation for the more fantastical elements, which mostly exist at the fringes until the startling moments when grotesque body horror suddenly bursts to the forefront.

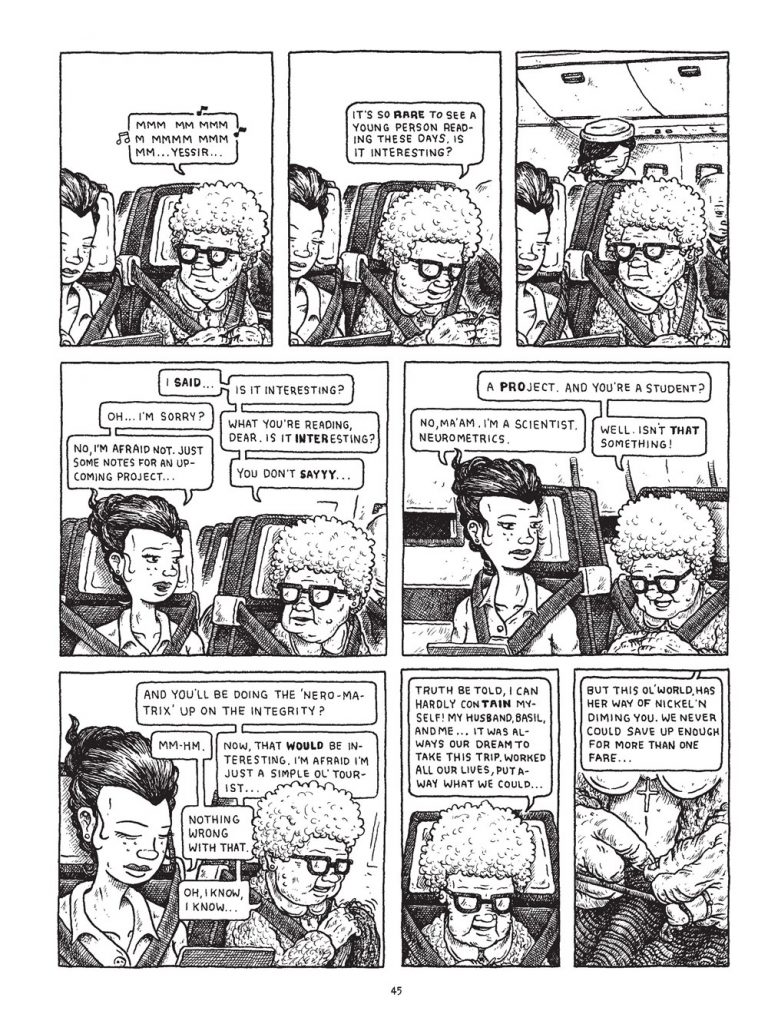

Cotter’s art is dense and intricate, with a slightly rounded, cartoony quality to his linework that imbues the figures with distinctive personalities. Melody is a fantastic example of Cotter’s ability to develop character through the quality of his cartooning alone. Her personality seems inscribed in her posture and the lines of her face: a stubborn oval of a snub nose, a neat inverted triangle of freckles on each cheek, a stern set to her lips and eyebrows, her thick hair generally pulled up into a messy bun with straggling strands jutting out. Cotter applies a broad cartoony vocabulary to the characters’ expressive faces, embodied especially in the sarcastic Melody’s smirks, scowls, and side-eye glances.

There’s a pleasing physicality and solidity to Cotter’s figures, and the world he draws is packed with detail. The spaces are realistically cluttered and decorated, and every stray background object is rendered with the same weight. Shadows and patches of darkness encircle the characters everywhere, intensely cross-hatched and textured. Cotter never skimps on a detail.

The same sensibility extends to the writing. The dialogue is naturalistic and eloquent, with real attention to the way people speak and the way different voices interact with one another in the flow of conversation. Early on, Melody has a mostly one-sided conversation with an elderly woman on the shuttle ride to the Integrity, in which the older woman blithely rambles on while cutting off and ignoring Melody’s replies. Though in some ways it’s a simple stereotyped gag, Cotter structures it well as an introduction to Melody, who’s frequently condescended to even though she’s often the smartest one in the room. Later, there’s a multitude of voices and conversations, ranging from dry technical recitations to stoned patter to snippy interactions with the stiff Lance, who’s obliviously insistent despite Melody’s many rejections. Cotter has a knack for making even the deliberately mundane dialogue sing in its own way, with subtle jokes and revelations of character embedded in the banalest exchanges.

Structurally, these two volumes of Nod Away fit together in interesting ways. The first volume proceeds mostly chronologically towards a pair of violent, horrifying set pieces. This arc is often interrupted, though, by mystifying detours which hint at larger mysteries beyond the ones uncovered thus far. Throughout both volumes, there’s a secondary narrative involving an unnamed shaggy bearded man who awakens in some kind of hibernation pod and then wanders across a barren alien landscape. These unexplained segments generally last just a few pages at a time, providing tantalizing evidence of just how much ground this series may eventually cover.

Cotter often transitions back and forth between the two narratives with abstract and semi-abstract connective tissue. These doodles and networks of tangled lines recall Driven By Lemons, Cotter’s abstracted meditation on depression from 2009. In that deeply personal and affecting comic, brief narrative fragments are interspersed with lengthy abstract showcases in which the world unwinds into streams of cable-like lines and beautifully painted smears. In Nod Away, these intrusions are at first used for title pages introducing each new section, but soon they bleed into the fabric of the work itself. More and more, especially in the second volume, the abstractions, which initially suggest computer circuits or neural pathways, begin to look like deconstructed versions of more tangible imagery, knitting together into glimmers of form. There’s a particularly telling section in the second volume where a moment of violent trauma collapses into disassembled lines, as though it’s too much to bear without erasing its particulars. At first, these lines still trace the contours of the room where the event took place, but the figuration quickly breaks down and the lines re-formulate into a circular image, which then resolves as the mouth of a cave that the unnamed bearded man is approaching. It’s elegantly done and formally dazzling, as well as suggesting some deeper revelations still hidden within the story’s structure.

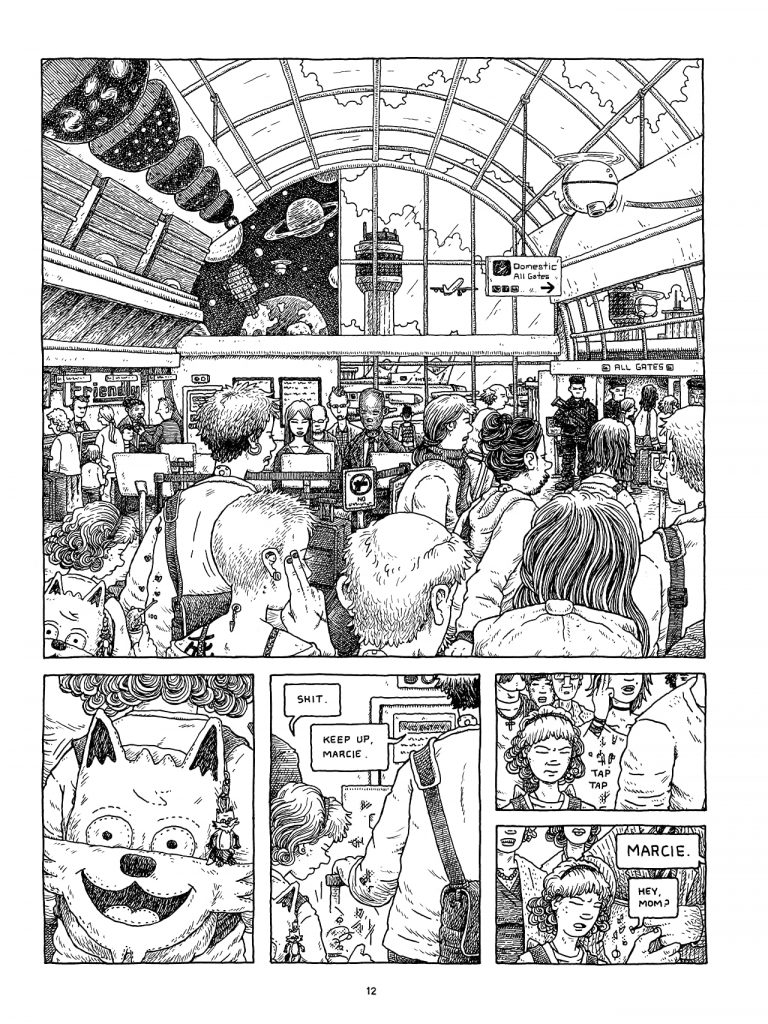

This kind of unexpected connection highlights the series’ gradually increasing focus on ways of thinking about and visualizing the world. The second volume includes a lot more of this interstitial drawing. In some places, the lines weave between panels, their shapes filling in the gutters and drawing literal connections between the curve of a cloud in one panel and the spindly autumn branches of a tree on the facing page. Indeed, the second volume opens with a single dot expanding to a line, then a dense tangle that gradually coheres into an aerial view of an airport’s layout, leading into the opening image.

The second volume does a lot to expand and build upon this world. Where Nod Away’s first volume was a claustrophobic character study and creeping piece of space horror, this second volume jumps back in time after briefly acknowledging the first volume’s cliffhanger ending. In terms of genre, the horror has mostly been left behind, along with the space station setting, in favor of a psychologically probing doomed romance.

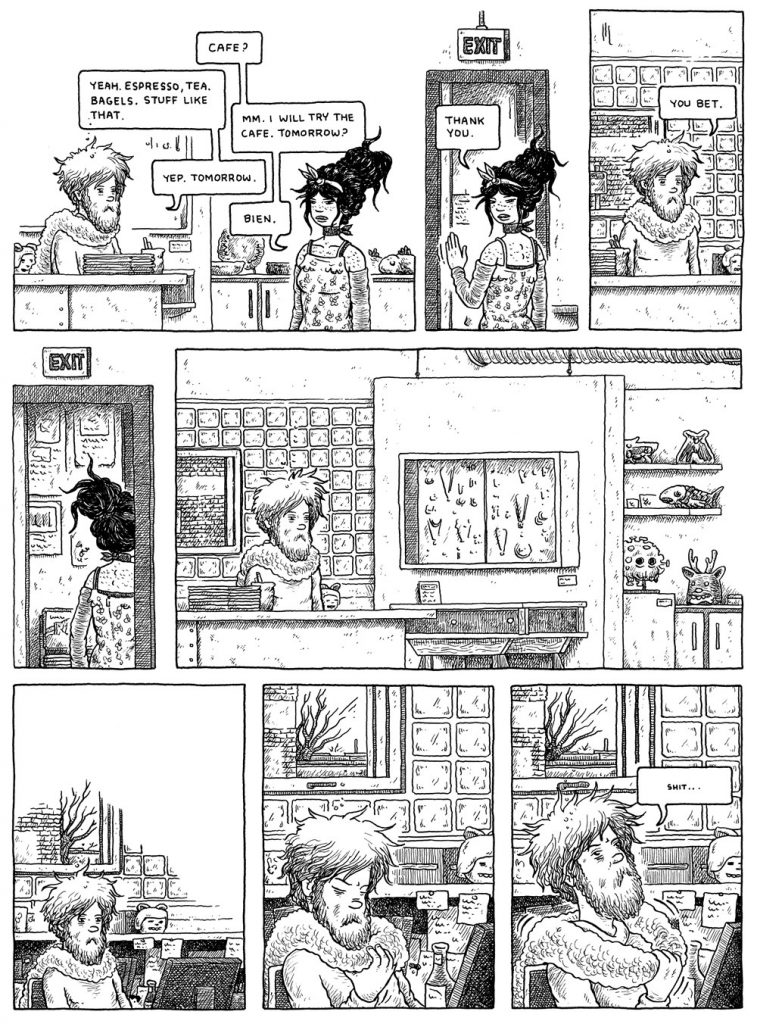

This volume introduces Walt, a freelance illustrator and wannabe cartoonist working as a clerk and living somewhat aimlessly in Chicago. He meets and falls for Aveline, a French immigrant working in a café nearby. Walt is drawn inexorably towards her despite the hints of darkness in her personality, and despite the fact that their relationship never quite consummates in the way he wants. There’s more than a tinge of “manic pixie dream girl” cliché about this relationship, but Cotter fleshes out and enlivens the well-worn conventions. Over the course of the book, it becomes obvious that Walt is haplessly projecting his shallow desires onto this troubled woman, who refuses to be possessed or even really understood by him.

As in the first volume, Cotter’s designs instantly communicate a great deal about the characters. Where Walt is a nondescript hipster dude, most of his face hidden behind a beard and a formless mop of hair, Aveline is drawn with tremendous specificity and energy. Like Melody in the first book, she’s speckled with freckles, her dark hair spiraling high above her head in a gravity-defying beehive. After a key transformation later in the book, she becomes eerie and otherworldly, her hair chopped off and her eyes black, unreadable.

Beyond freeing the story from the confines of a single location, this second volume is a looser, more sprawling affair. It’s a much longer tome than the first one, and Cotter skips around in time and space more. The chronology is still pretty straightforward, essentially a frame wrapped around a long flashback, but there are ambiguous transitions that leave long time gaps, sudden shifts to new locations (including Walt’s father’s farm in the country), and more frequent interjections from the secondary narrative. What’s sacrificed in terms of focus – the first volume was a truly intense horror experience – is channeled instead into an increasing sense of scale. This is where Cotter really starts building out the contours of the larger narrative. After the twists and turns laid out here, both in the origin story flashback and the sections that take place following the first book’s cliffhanger, there’s a sense that the story could go basically anywhere from here.

That’s an exciting feeling, especially since Nod Away is already such a rich and potent series. It’s so grounded in its characters and their everyday dramas that at times it’s easy to forget how much weirder material is circling around those ordinary moments. There’s a fascinating texture to the series that becomes especially apparent in the second volume, in which domestic and romantic dramas bleed seamlessly into the ideas about technology warping the mind, body, and spirit. Cotter’s a patient and naturalistic storyteller, so when he shatters that naturalism it can be genuinely shocking. This happens in the first volume when teleportation technology becomes a gateway to gory body horror, and in the second volume with an imaginatively disturbing dream sequence – a dream, best of all, which isn’t just empty shocks but reflects the psychological horrors Cotter explores throughout much of the rest of the book.

By privileging emotion over technology, Cotter is crafting a sci-fi world that’s built more on the people populating it than the heady ideas that define its boundaries. The ideas – about memory, technological dependence, and the very nature of reality – always arise from the flawed, human characters and their relationships, and are all the more deeply felt for it. Beautifully drawn, provocative, and remarkably intelligent, Nod Away is likely to be one of the most exciting ongoing sagas in comics for many, many years to come.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply