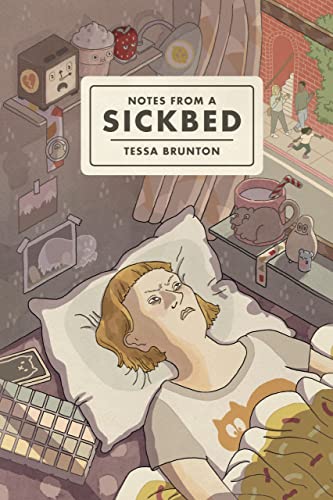

Tessa Brunton gives a lot of details as to the tone of her graphic memoir, Notes From A Sickbed, from the cover alone. Surrounded by a variety of comforting objects like toys, art, and a cheerful-looking mug, the center image on the cover is her laying her head on a comfortable-looking pillow. The stark white of the pillow is meant to draw her attention to her face in the center of the page, and there is a viscerally resentful scowl on her face. In the upper right-hand corner of the page, you see active people living their lives outside. What should be a quiet moment of repose is instead seething with anger. The repose is the annoying solution to the problem: Brunton finds herself needing to stay in bed thanks to unexplained fatigue and pain that can only be slightly ameliorated with total bed rest. Notes From A Sickbed is her attempt to provide a modicum of humor and grace in the face of mysterious, rage-inducing, and near-constant fatigue.

Brunton explains in her introduction that she spent several years trying to work around her hard-to-diagnose chronic illness that frequently left her completely bereft of energy. She reveals that, after six years, she was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. It has no cure, but understanding what it is at least gives her a slightly wider array of options. However, this book focuses on the five years before that and is much less about the medical aspects of this period than it is about the lived moments in a sickbed, desperately trying to keep it together.

What’s interesting is that in nearly every situation, Brunton’s instinct inevitably turns to think of things in terms of narrative. In each brief vignette about her experiences, she often discusses things she does that might help cheer her up. One such solution is surrounding herself with beautiful, cute knick-knacks. On the one hand, she thinks having these tchotchkes nearby could fill her with joy, as each one has its delightful narrative she can explore. However, she also imagines feeling trapped and surrounded by her things, their nightmares turning nightmarish. Even in this scenario, Brunton’s mind turns to thinking of Rube Goldberg-style solutions for conserving energy, as the objects are arrayed to accomplish simple tasks in an absurd, overly complex fashion.

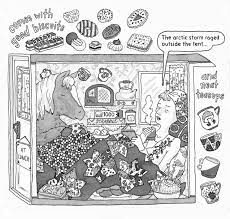

The first half of the book is spent redirecting the fury Brunton feels about her situation without going into much detail as to how and why she got there. All the reader knows is that she is bedbound, and she is desperate to find ways to cope with this. In the hilarious “Haunted House” chapter, she describes living underneath a bunch of cheery college girls and finding herself loathing their uninterrupted lust for life. After watching a horror movie about a house that devours nice, friendly people, she finds that she identifies with the house. She details all kinds of ways she could haunt those girls, annoy them and terrify them, especially when she realizes she can’t drown them out. The chapter “Bedmobiles”, on the other hand, goes in a different direction, where she imagines elaborate inventions that would allow her to stay in bed while still exploring the world, like a cake-shaped bed tower for parties. Another chapter featuring her friend’s story of horrible woe stuck in the woods makes her wish for the active, ridiculous discomfort of a miserable camping and paintball trip over fatigue-forced ease.

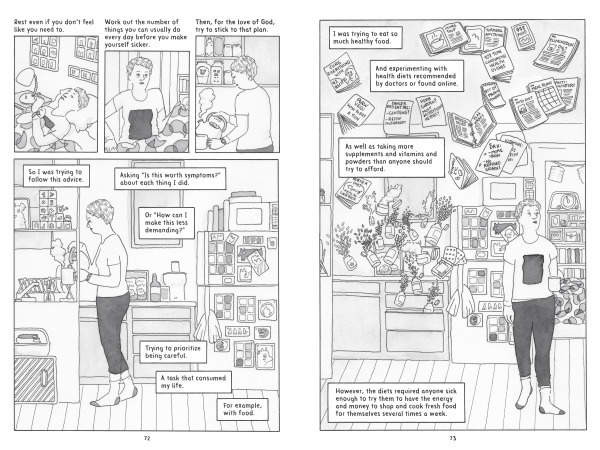

It’s not until the middle of the book and “Mistakes” that Brunton takes a step back and reveals her slow descent into forced isolation. This extended section reads like its own horror story. Early in her sickness, she wakes up feeling well on her birthday and she goes to a movie with her parents. All seems well, until the next morning when she starts to understand that activity, any kind of exertion, creates symptoms. The problem is that there’s a lag between that exertion and the symptoms themselves, adding to the maddening quality of it all. Still, Brunton doesn’t linger on the symptoms which include debilitating nerve pain, brain-shattering headaches, and total physical malaise. The symptoms are awful, but the worst part for her is the total sense of helplessness that she feels, and this is what she talks about the most. The only thing that helps is rest, but the respite is always short-lived. There is no recovery, only temporarily feeling better and developing a calculus for activity. The worst part is that Brunton is a social person who wants to go out and do things, and finds herself having to repeatedly cancel commitments. Even eating becomes a minefield, as she’s guided to a thousand quack “healthy” diets in hopes of improving her symptoms. There’s a passage where she takes on a one-day cartoonist residency, and, by the end, she’s barely able to drive herself home.

Brunton’s illness becomes her identity, and she is bitterly resentful that it makes her feel like a stone slowly being eroded by the water. She’s realistic about her old life; she was stressed and dealing with an unstable lifestyle and lived out of balance. But at least these were her choices. She’s now a slow-acting time bomb, whose survival depends on total inaction and anhedonia.

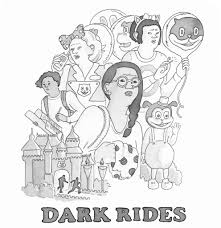

The final chapter, “Dark Rides,” takes the narrative in another direction. In an earlier chapter, Brunton describes how she was capable of becoming so obsessed with an art project that she would neglect things like sleeping and eating in favor working on it for hours. While not capable of that kind of labor now, the one thing her illness can’t touch is her imagination. Her brother suggests collaborating on a murder mystery set at a park like Disneyland, and Brunton just runs with it. She becomes obsessed with Disneyland’s history and setup, and slowly makes the story her own. However, she feels it’s not enough; she needs to actually go to Disneyland to get a real feel for it and take reference photos.

Miraculously, she’s able to go with her mom to Disneyland, her first trip in five years. She’s able to do everything she wants and take every photo she needs. Her illness doesn’t stop her. When she’s home and feels the inevitable symptoms coming on, she realizes that in order to do the comic the way she wants, it will take her nineteen years. It’s an impossible task. She breaks down in tears. Then she thinks about a lady losing her cat, and suddenly a book called “The Commune” appears in her head. Then another book about a Halloween curse. Then another about a haunted space colony. The final image takes place at the colony, with someone in a vehicle that looks suspiciously like one of the Bedmobiles earlier in the book. She just can’t help herself.

This is the best kind of graphic medicine book. It’s not didactic, nor does the narrative center around the course of a disease and its treatment. The disease here, while it certainly manifests physically, has an impact that is almost existential. Brunton isn’t interested in why she has the disease and is also not interested in explaining how her life changes after she’s received an actual diagnosis. The point of her narrative is that the one thing her disease can’t take away from her is her imagination and her will to create. Even if she can’t put pencil to paper, she can still spin yarns in her head. She can still bring herself this tiny bit of joy, and that’s enough to get through a day. Brunton reminds the reader that in a graphic medicine narrative, it’s the quotidian details of living with an illness that is every bit as important as dramatic events like surgeries, ER visits, and radiation therapy.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply