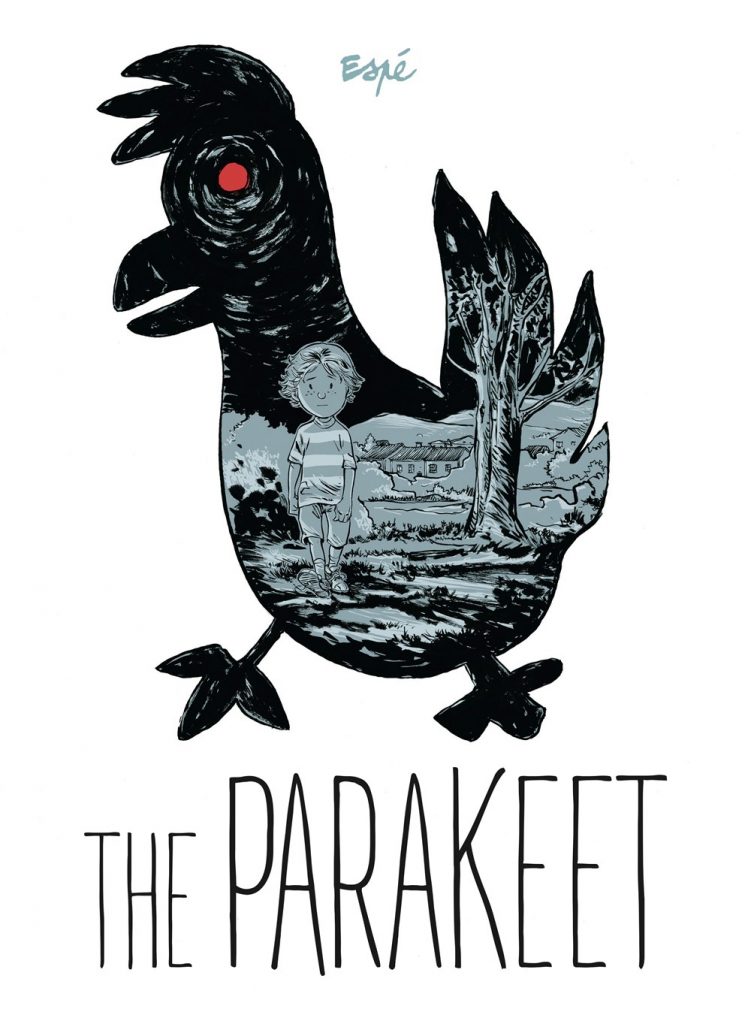

Every once in a while, you pick up a book already knowing you’d like it, but, even then, it exceeds your expectations in the best possible ways. The Parakeet is one such book. I remember seeing the striking cover art—a silhouette of a crudely inked parakeet encompassing the diminutive figure of the protagonist against the backdrop of a desolate landscape—and being immediately drawn to the sketchy visual elegance that’s quintessential of comics. Published by Penn State University Press’s new Graphic Medicine centric trade imprint Graphic Mundi, The Parakeet is a graphic memoir by the French cartoonist Espé [and translated to English from French by Hannah Chute], about the author-protagonist’s experience with an absentee mother and his mother’s struggle with bipolar depression and schizophrenic tendencies.

Espé positions Bastien, the younger version of himself, as the narrator and offers an intimate look at his mother’s debilitating illness: “My name is Bastien. I am eight. Mama’s been sick since I was really little.”, the story begins. The explicit redrawing of his mother’s episodes (a word that Bastien and his family uses for the times his mother loses control and has to be taken to psychiatric facilities) may be hard to read for some, but Espé’s visual storytelling is sensitive, tender, delivered with care, and loaded with affect. The narrative is organized into montages that alternate between Bastien witnessing his mother’s illness helplessly and finding brief pockets of respite in the intermittent periods between her episodes. We follow Bastien, from one memory to another: each recollection focuses on one object such as the “The Shirt with the Belts”, in which he narrates a traumatic memory of witnessing his mother being put into a straitjacket by mental health professionals, or on an overarching theme such as “Baby Blues” where he suspects that had it not been for him, his mother would never have slipped into postpartum depression and eventually into severe bipolar depression.

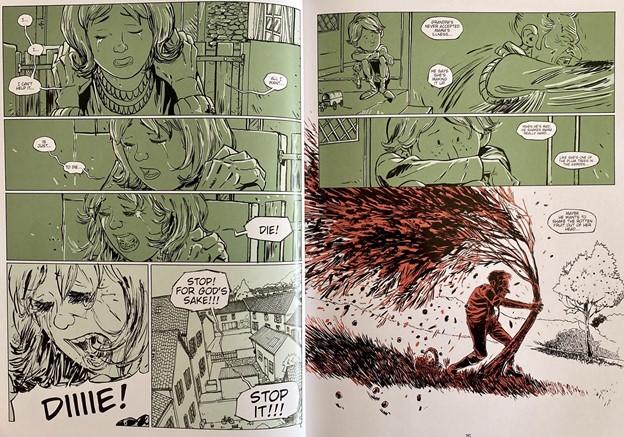

The discomfiting nature of their relationship, sweet and nurturing one moment, explosive and lonely the next, is narrated skillfully using the sequential and simultaneous nature of comics. In the chapter titled “Grandpa”, Espé makes room for two accounts: the first shows the reader how his grandfather never quite made peace with his daughter’s illness. It is narrated in the form of sequential panels that reveal a particularly volatile conversation between Bastien’s mother and his grandfather. An anxious-looking Bastien is seen in the background, hiding his face behind his arms; he adds another layer of narration to the scene to provide additional context to the reader. The second account comprises a half-page spread with a sprawling red and black inked image of the grandfather desperately shaking a large tree. The scene manifests his perpetual frustration, both in its metaphorical rendering as well as in the way it is drawn, departing from the sap green color scheme seen in the rest of the chapter. Unenclosed by borders, and bleeding into the panels preceding it, the moment seems to indicate the anguish he feels about his daughter’s illness is ever-present and not confined to this one incident.

The Parakeet also boasts of artwork that excels in the comic medium. Espé’s sketchy but bold linework, ingenious use of perspective, and adept shadow work are all meticulously deployed to evoke a strong emotional response from the reader. It is reflective of the generative capacity of the medium to stage traumatic events, as seen in the artist’s staging of young Bastien’s loneliness palpably, for the reader to not just read but to experience vicariously. Instead of directly telling the reader about his coping mechanisms, Espé takes us back to certain days from Bastien’s unusual childhood to show the reader what it was like for him growing up. In one bittersweet flashback, we find that after his mother undergoes electroshock therapy (currently known as electroconvulsive therapy or ECT), he earnestly tells his friends at school that his mother might be a superhero. Subsequently, we see Bastien drawing various superheroes, his mother, and his mother as a superhero on more than one occasion. In that, The Parakeet, implicitly espouses the power of drawing in processing grief and in reimagining our worst days— a recurring concept in Graphic Medicine texts.

The narrative makes eloquent use of the visual grammar of comics to leap from one childhood memory to another without appearing fragmented. Sparse but powerful use of onomatopoeia, coupled with a monotone color scheme that shifts from greyish blue to sap green to a blazing crimson depending upon the urgency of the scene makes the story come alive. Comics artists often use shifts in color tone to emphasize the mood of any given scene, but the efficacy of Espé’s transitions is what makes The Parakeet so visually sound. Set against a backdrop of realistically drawn small towns and detailed interior architecture, his characters are nearly anatomically realistic, apart from their slightly larger heads and exaggerated expressions. The result is a minimally but distinctly stylized set of characters conducive for leaping into visual metaphors when required, such as the time when the mother and son are out shopping in the town and her invisible illness follows her in the shape of a looming monster. In a particularly piercing moment, Bastien narrates, “Mama’s like Jean Grey in the X-Men. She might explode any moment! But no one knows…except me” (67). With the exception of the scene in which he is seen determinedly peeling off the wallpaper at his grandmother’s, ostensibly to feel closer to his mother who is having an episode in the room on the other side of the wall, Bastien displays no outward or explicit sign of distress, only a quiet yearning and a capacity for resilience and grace that seems almost unusual in a person so young.

The last memory of his mother, he writes, is a stuffed animal—a misshapen parakeet— that she made for his tenth birthday while she was at a special facility in Lavaur in the last few weeks of her life. He writes that it was ugly and did not look like a parakeet at all, but he thought it was wonderful. The narrative culminates in an epilogue, years down the line from the flashback: adult Bastien is in a maternity ward with his partner, who asks,

“Bastien, someday you have to tell me where you got that lumpy stuffed animal that’s been lying in your desk drawer the whole time I’ve known you.”

The Parakeet joins the ranks of the increasing number of both creative and scholarly works that are being produced in the rapidly growing field of Graphic Medicine which focuses on “the intersection between the medium of comics and the discourse of healthcare” (Ian Williams, et al.) Espé’s grasp and depiction of his and his mother’s vulnerability and the meticulously observant visual descriptions of his family, the town in which the story is set, and “psych homes” in southwestern France, are a testament to how the image-textual nature of comics can accommodate multiple perspectives and create generous and empathetic narratives. The narrative is never detached from his mother’s acute suffering, yet it is not quite her story that he is telling. Instead, it is his story, and a tribute to his relationship with his mother, and their tenuous yet unindulgent love in the face of an unrelenting illness, depicted with rare emotional depth and compassion.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply