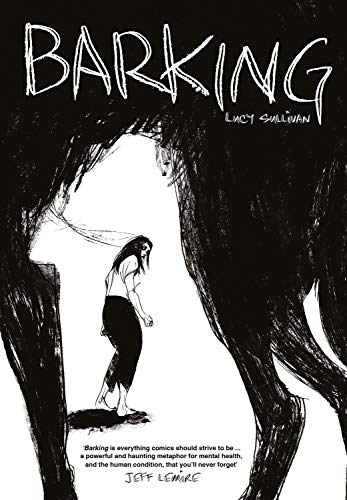

Lucy Sullivan’s Barking debuted back at 2019’s installment of the UK comics festival Thought Bubble, although it was launched properly at the start of last year, and, since then, it has become something of a word of mouth sensation, taking up various spots on 2020 highlights lists in the UK and elsewhere.

We’re introduced to protagonist Alix Otto atop a bridge, imagining her suicide, hounded by a pitch-black wolf-like figure. Eventually, after Alix is restrained by police and institutionalized, we subsequently learn that her depression has been sparked by the death of her friend twelve months prior, and the various degrees of grief, confusion, and guilt that have ensued. Barking follows her journey as a tortured soul who eventually finds some clarity and relief thanks to her fellow-sectioned cohorts in the hospital.

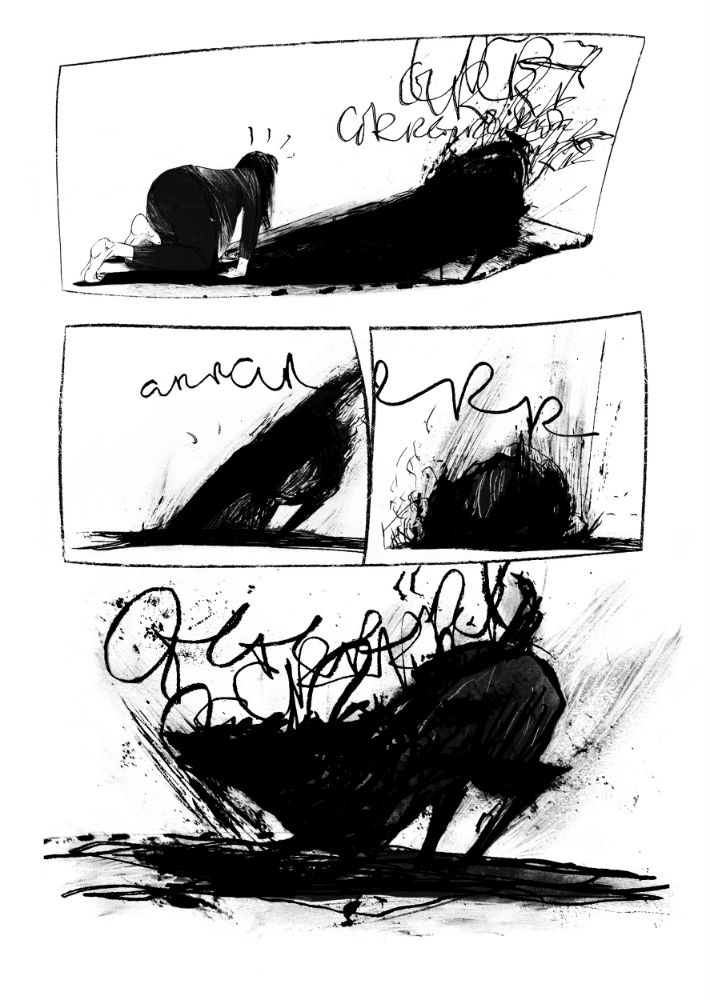

Sullivan’s art is the thing that encouraged me to trust the hype and get myself a copy of Barking, and it’s no doubt one of the reasons for its success amongst comics aficionados. The book’s world is rendered in scratchy and frenetic black and white, with what looks like chalks and inks. It’s somewhat reminiscent of the earthy quality of Eddie Campbell’s work in From Hell, although, befitting Alix’s disjointed mindset, the page arrangements are loose rather than regular; panel frames bend and break to the characters’ actions. The characters themselves are somewhat fluid and febrile, reminiscent of the flexibility of Alberto Breccia’s caricatures in Perramus.

I must stress that these references should only be taken as rough guides. Sullivan has produced a singular visual voice, one where the real and the unreal and metaphysical exist in the same plane without one making the other seem ridiculous or unbelievable. The best example of this is Alix’s wolf/dog stalker, which comes to life through Alix’s own shadow, and embodies her internal violence. There’s a physicality to the way in which Sullivan’s style pulls the figure of the wolf out Alix’s shadow which makes the animal more than purely a symbol, it highlights the comic panel’s ability to be much more useful than something that just represents “real life”, it can represent external and internal worlds with equal weight and measure.

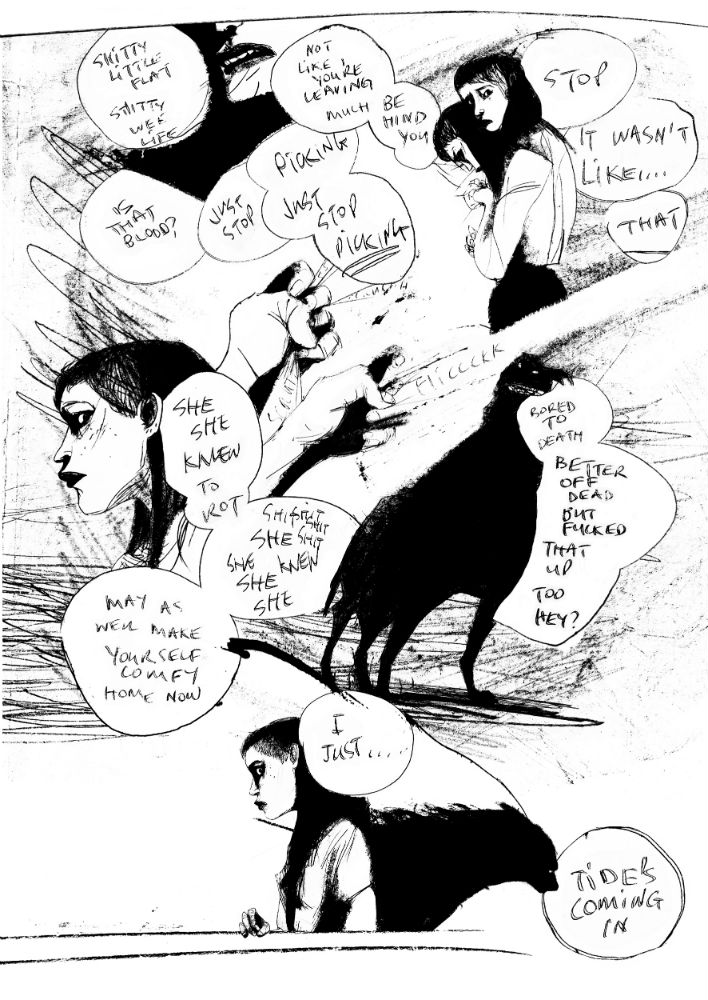

There’s a general rule that says the best comics text is whatever makes the least amount of impact on the page and is least distracting from the action. Barking goes in the complete opposite direction. Dan Berry’s typography, based on Sullivan’s handwriting, feels embedded in the visual track. Sometimes, Sullivan doesn’t bother with providing the outline for the speech bubbles. Instead, she lets the words be seen as physical objects caught in time. Her onomatopoeia also feels very much part of the drawings. The indistinct mutterings that float across London in the final panels transmit a haunting feeling.

This doubling up of text as both transmitter of words but also as a part of the visual language of the diegesis not only helps to increase the sense that words and sounds have a material effect, but it also helps distract from the sometimes cliché script. At one point a peer called Lozza wants “to read” (I presume tarot) for Alix. Informed by the cards, Lozza instructs Alix to “own the beast within” and “trust in life to see you right.” To repeat a cliché myself: clichés are clichés because they’re mostly true, or at least speak to some truth, but that doesn’t make them exciting to read, and the above two quotes definitely seem too similar to saccharine inspirational memes, and that feels even more true given the dark and daring visual track.

There are individual moments where the progression of action remains somewhat of a mystery, and recognizing characters across the pages isn’t always the easiest task. In the main, however, what seems somewhat obscure the first time around becomes clearer on rereadings. Barking is a relatively short book but one that demands attention and care from the reader, and for that, it should be celebrated (thank God! Comics that don’t make hay of the medium’s “easiness”). As its popularity grows, so will the number of critics that treat it primarily as an instance of graphic medicine. Sullivan’s own afterword and other reviews put this aspect of the book front and center. Like some of the most famous early instances of the graphic medicine genre, such as Charles Burns’s Black Hole, for instance, Barking is a comic that can also be recognized as a part of the horror tradition. Its embracing of the animalistic, its exposition and critique of what Michel Foucault described as heterotopias of deviation (places “in which individuals whose behavior is deviant in relation to the required mean or norm are placed”), and its preoccupation with the ghostly combine to make Barking a work of both graphic medicine and horror. Given that professional medicine’s roots lay in magic, witchcraft, and superstition, it’s not surprising that the combination of the otherworldly and bodily continues to be a fruitful space for artists to draw from.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply