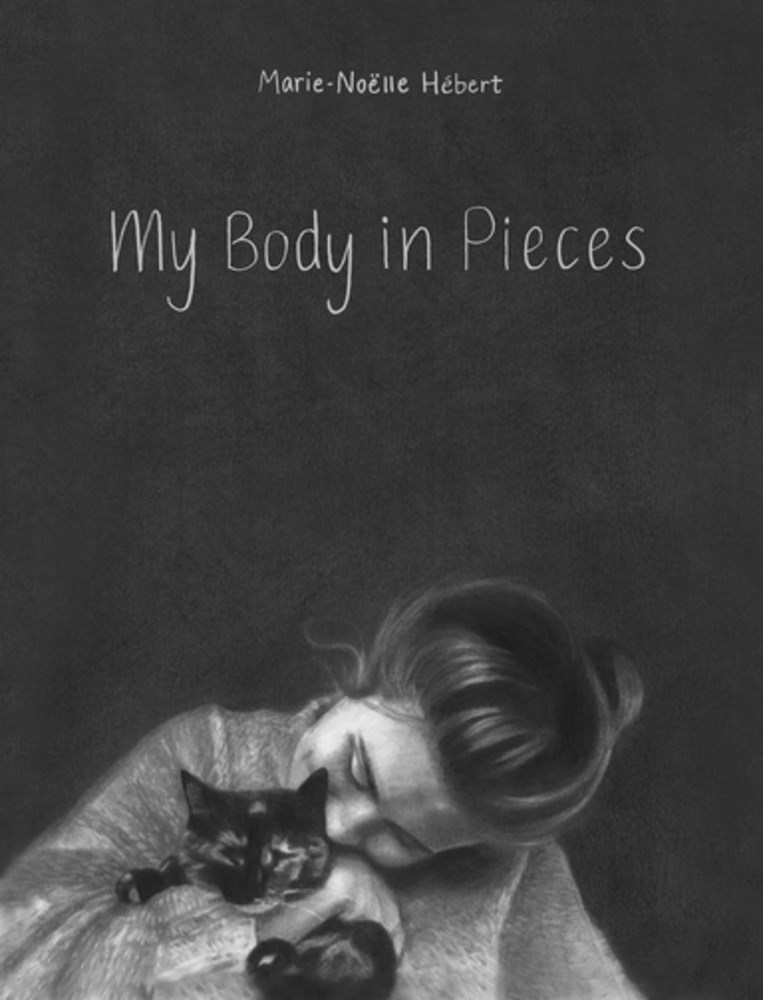

My Body in Pieces is the debut long-form comic from Canadian artist and graphic designer Marie-Noëlle Hébert. Originally published in French in 2020, it was awarded the Prix des libraires du Québec that same year and has since reached English audiences via Groundwood Books, translated by the publisher’s fiction editor Shelley Tanaka.

The book is touted as a YA comic, but, while the straightforwardness of the language and the age of the characters definitely make it appropriate and relevant for younger readers, Hébert’s art boasts a depth and darkness that makes it an engaging read for age-unspecified readers.

A memoir that traces the artist’s teen years and early 20s, My Body in Pieces is primarily about Hébert’s once self-destructive attitude to her weight and body, with focus being paid to her eating habits and concerns around normative beauty standards.

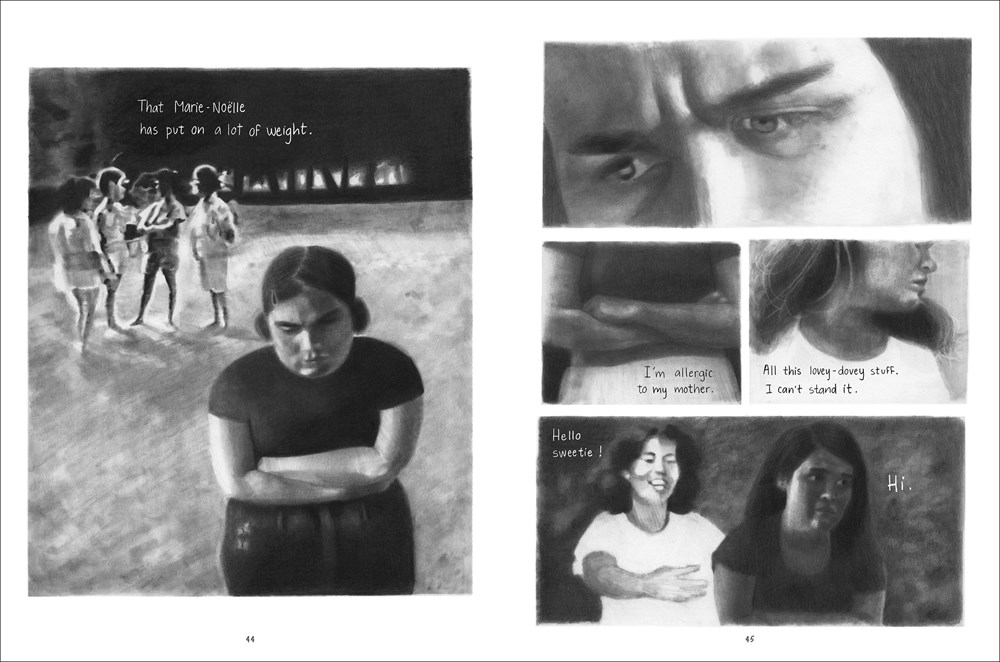

We’re introduced to the author’s cartoon avatar dealing with the cycle of consumption, guilt, health worries, and depression that stalk her as a young adult, before being taken back to her childhood in Montreal where neither peers at school nor her family offer her the sort of loving support you’d hope would be offered.

An early sequence in which Hébert literally tries to eat one of her toy princesses is particularly striking. This is something kids do with their toys, of course (I’m pretty certain my body can’t have ever digested that Lego brick I once swallowed), but it also works as a metaphor for the way in which beauty standards and expectations of girl- and womanhood (and manhood, for that matter) are digested through cultural objects such as these.

It’s a well known fact that if Barbie were real, the proportions of her body mean she wouldn’t be able to stand up. Yet she is the traditional and impossible to meet patriarchal “standard” against which young women are often expected to judge themselves. Betraying the cruel logic of consumer culture, an impossible body in a plastic state becomes a communicator which tells a body of meat and bones to consider itself a failure by nature. Barbie is actually an American variation on a German doll, itself based on a cartoon drawn by Reinhard Beuthien that regularly appeared in Bild, in which a supposedly representative figure of a post war, young and independent West German woman was satirized as being “a golddigger, exhibitionist, and floozy.”

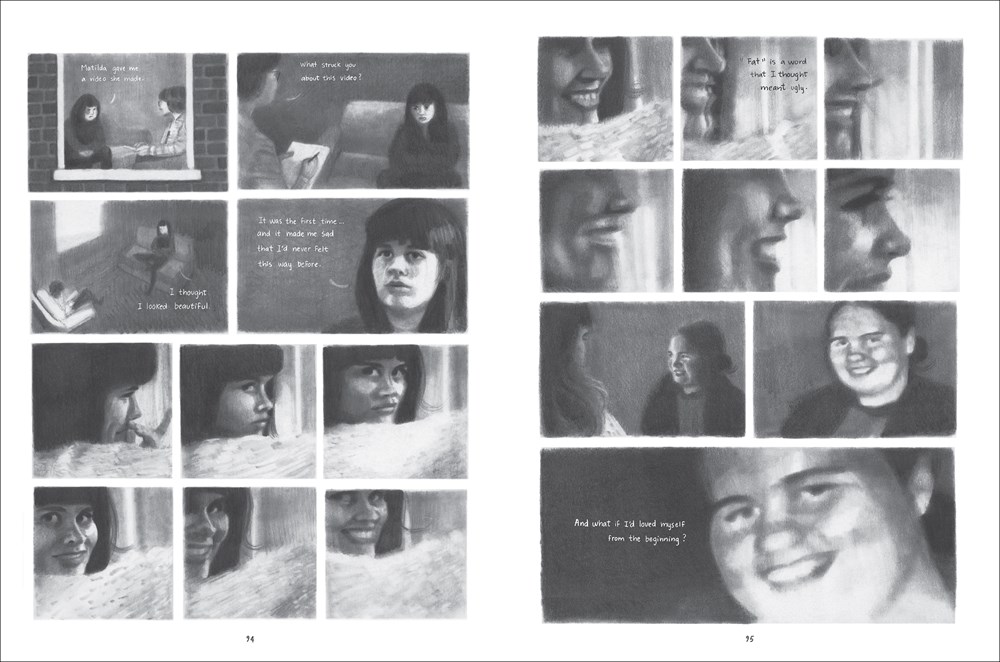

Hébert’s textured black and white art, drawn in graphite pencil, is a necessary counterpoint to Beuthien’s representation of women. Her figures are sometimes stretchy and cartoonish, other times distant and out of focus, and elsewhere closer to a photorealist aesthetic. The reader is often presented with visual metaphors, such as Hébert being suddenly submerged in water, tied into place by the roots of a tree, or being haunted by the hand of an unknown figure. These horror-inflected moments create a tense atmosphere, utilizing the horror’s genre’s basic function to make psychological fears and feels plastic. It doesn’t really matter if you are a certain way or not if everything inside of you is telling you it’s so. There’s one three panel sequence in which we witness Hérbert literally try to tug, pull and slide the skin from her face (“I want… to rip off… my face.”). My Body in Pieces thus succeeds in bringing together psychological and empirical experiences in the way in which they often bleed into each other in real life, and alter one’s perception of themself and the world around them.

As is often the case with black and white work, the art here produces a sense of melancholia; we are witnessing a life with all its vivid colours stripped away. It also allows Hérbert to liberally use pitch black backgrounds devoid of Mise-en-scène, moments when the world seems to disappear and her past self seems devoured by an overwhelming sense of isolation.

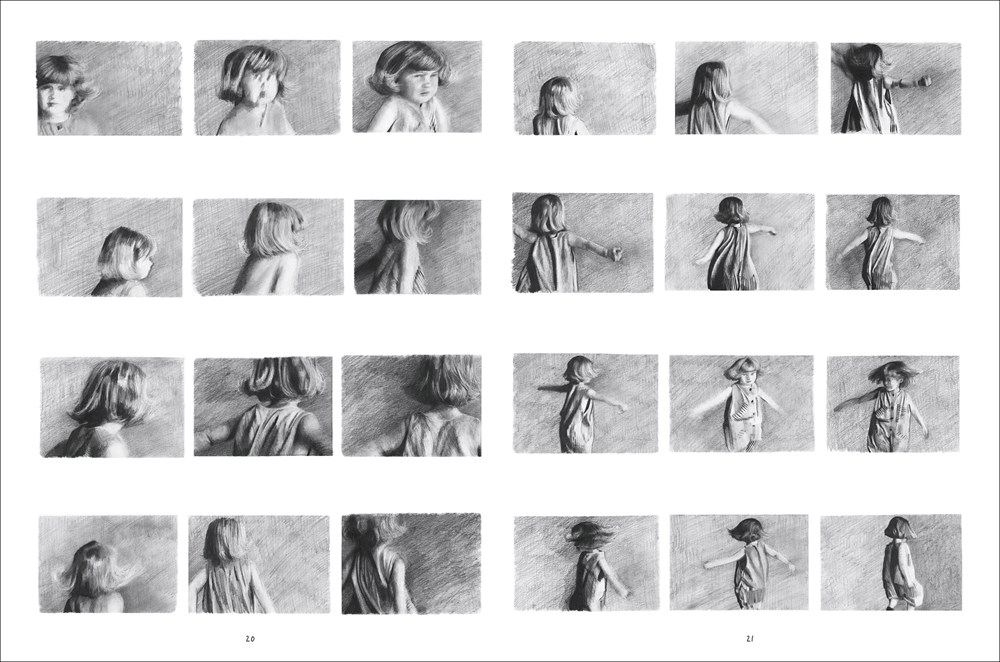

Two of the most uplifting scenes in the book are the wordless moments in which Hérbert depicts herself as dancing. A page towards the end of the book shows her moving with a friend to unspecified music (she tells us that as a child she often reproduced the dance routines of her favorite music artists). Earlier on, there’s a two page spread in which Hébert as a young girl twirls around, seemingly endlessly. These moments look to be ones of pure release and enjoyment of what the body can do: who hasn’t enjoyed those times when – dancing skills or embarrassment be damned – you decide to indulge the desire to move.

As Hébert gains independence, experiences, and makes the sort of friends that she always deserved, she develops the tools necessary to “listen to my body” and “be proud of myself.” One of the most affecting moments is when she returns home after a time estranged from her father in order to confront him about how his words about her body created an emotional weight that was hard to carry. His support for this part of his daughter’s story to be included in the book points to an acceptance of responsibility, and Hébert renders the moment in an honest and critical yet loving way. She presents us, not for the first time, with a series of panels that look like still frames from a family video shoot; the most minuscule moments of tenderness and movement are captured in her grainy and intimate style.

My Body in Pieces is a comic about someone building themselves, both physically and emotionally. It is also about the toxicity of addiction and how to liberate yourself in a culture that constantly applies normative pressures. Hébert gives plenty of thanks to her friend Matilde who she says “carried me when I couldn’t move forward anymore.” It’s true that others can break you down and make you feel small, but it’s equally true that it’s necessary to have others in your life that can make you feel whole.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply