Fantagraphics recently published a new collection of work by the Danish cartoonist Rikke Villadsen, titled Cowboy, which we plan to have a review of later this month at SOLRAD. Today, as a teaser to that eventual coverage, please enjoy a review of Villadsen’s The Sea, published by Fantagraphics in 2018.

Sometimes the best way to say something is to be direct. Maybe it is telling your friends that you love them, or telling the cable company you are going to cancel your service unless they give you a better price. Other times, it is more effective to come at your point in a roundabout way. Most comics tend to go for the first approach – get everything out in the open and go from there. But Rikke Villadsen’s graphic novel The Sea prefers the latter approach. Described as a “seafaring tale soaked in surrealism,” Villadsen’s The Sea uses a language of surreal images and dialogue to express a powerful feminist worldview.

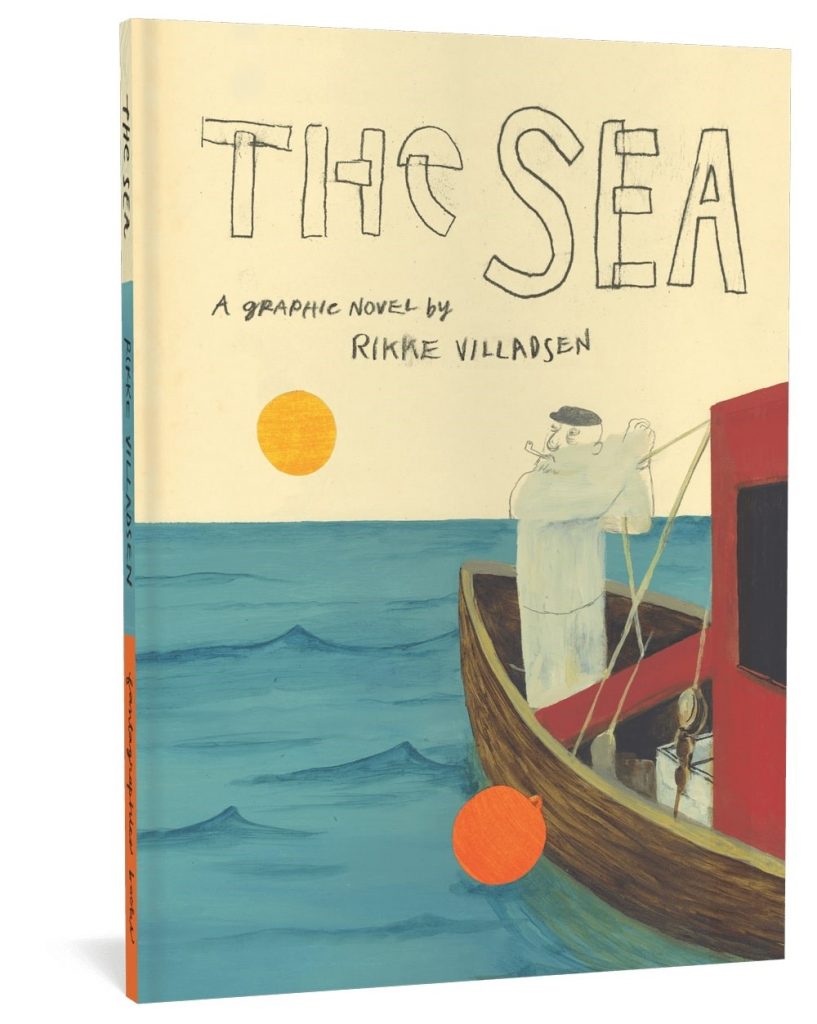

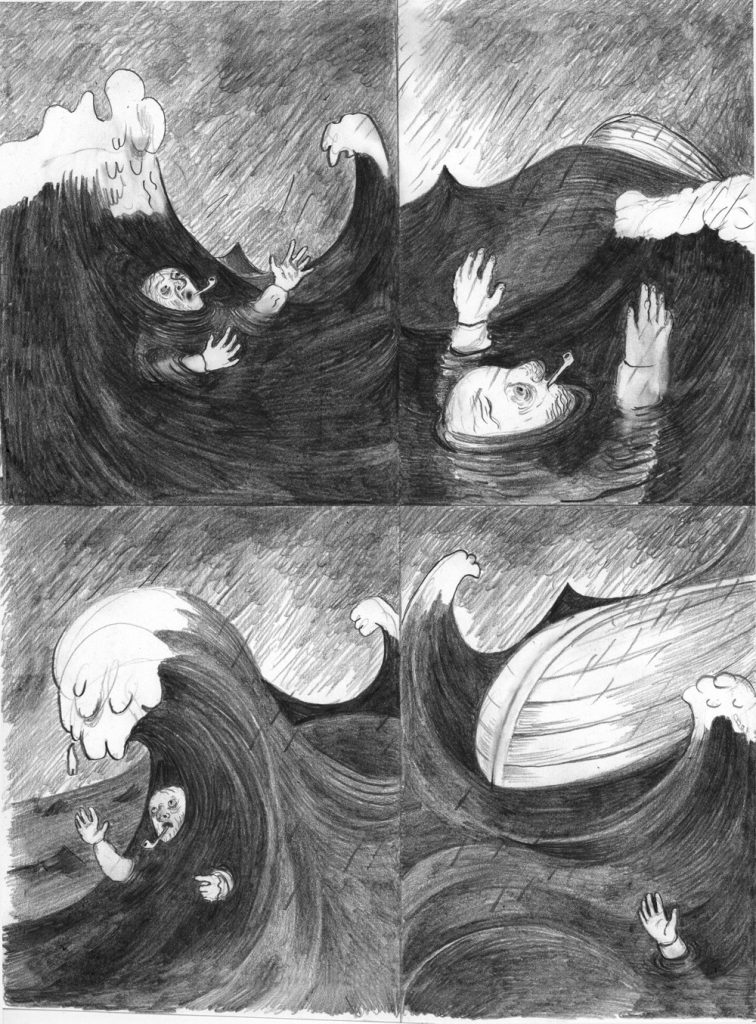

The Sea is a deluxe hardcover published in early 2019 by Fantagraphics, and is Villadsen’s first book to be translated into English. Villadsen’s cartooning is as lush as it is strange. With the first page turn you can see the power in it; Villadsen’s graphite illustrations are stunning, sometimes dreadful. Each of the pages of The Sea has a smokey quality, reminiscent of cartoonists like Cathy G. Johnson and Chihoi. Villadsen’s illustration captures the haze of a foggy sea, the dark crash of wild waves, and the pockmarked, craggy face of an old fisherman equally well. In the comics drawing tradition where thick definitive ink lines are the norm, and a historical precedent, comics drawn solely using graphite maintain an ethereal, ghostly quality, no matter how dark the pages get. And unlike most comics, where pencils are stripped away after inking and color, Villadsen’s labor on the pages of The Sea is very visible.

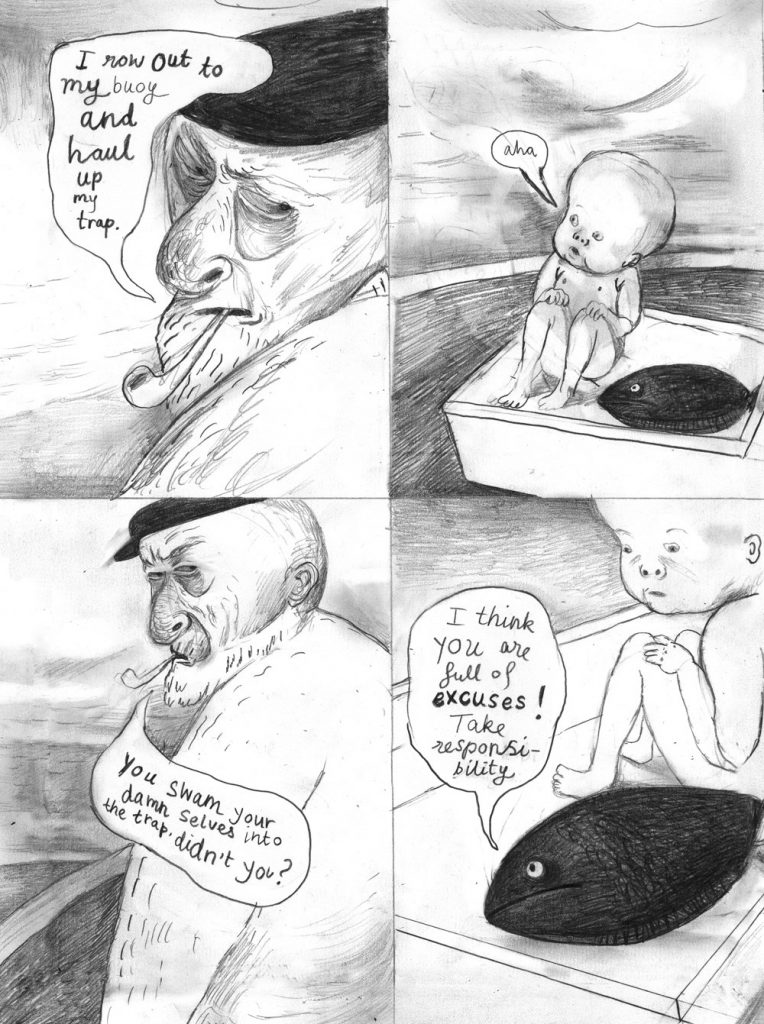

In The Sea, an unnamed fisherman sails out onto the water to collect his catch from a buoy trap. But instead of finding a large catch of fish, he hauls up a newborn baby and a talking fish; from this place forward, the book tips into a dense and endless madness that only ends when the final page is turned. On first read, the entire comic seems incomprehensible. The ebb and flow of time seems unpredictable, and the book swells to a stormy, chaotic conclusion. Importantly, it is hard to empathize with the main character and it is hard to be invested in his story or his life – which is precisely the point. Within the madness of The Sea, Villadsen begins a thoughtful evaluation of masculine toxicity, represented by the fisherman. Through subsequent reads, it is clear that this evaluation is much more like a dissection.

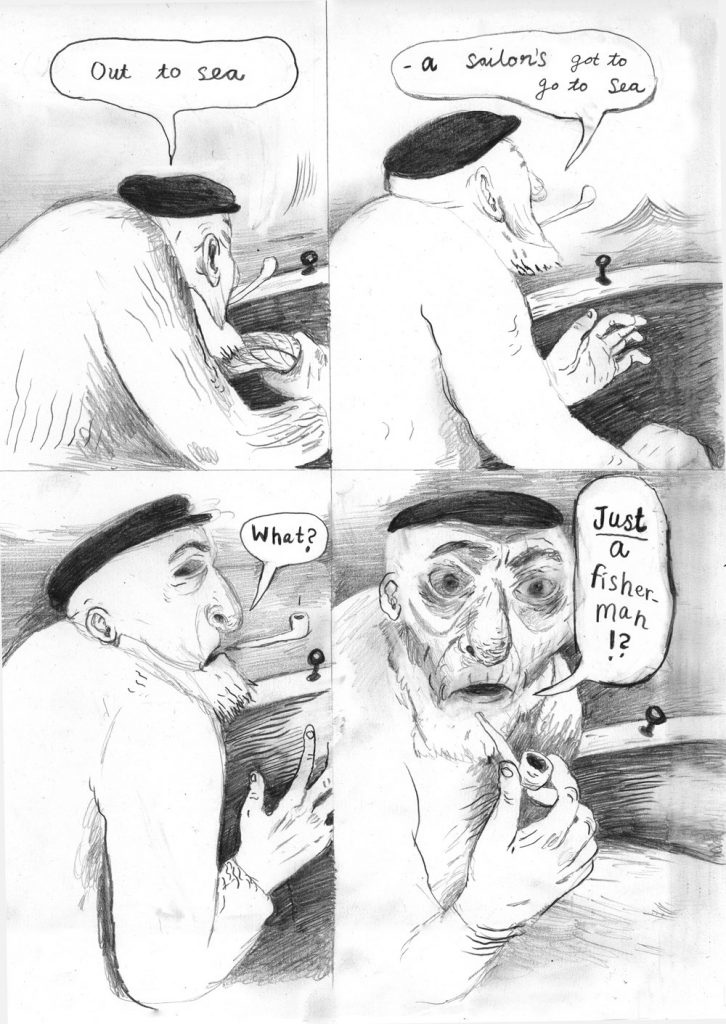

That dissection starts at the very beginning of The Sea as the fisherman describes himself as a sailor, with the tattoos to prove it. He talks in generalities about sailing around the world, his youth, and his exploits as a young sailor. Early on, he breaks the fourth wall to “argue” with the reader about his credentials. But for all his bluster, he seems unable to accomplish some of the basic tasks of sailing, at least intentionally. More inclined to puff on his pipe (one of the definitional items of a sailorhood) than actually do anything meaningful, he shocks himself when he finds his buoy trap on a foggy sea. The fisherman likes the affectation of sailing; tattoos, accordions, pipes, but has no sense for the larger actions of sailing. In a later part of the book, beset by gulls, the man gets sea sick and then throws an anchor over the side of the boat without an anchor line. The fisherman wants to play at being a sailor, and lies to himself and to the reader about his identity. His two captives, fortunately, see right through him. The child and fish are something like the moral core of the book, and they point out the fisherman’s lies and mock his foolish behavior.

The fisherman likewise tries to convince the reader of his authenticity using a series of tattoos, each of them images of naked or nearly naked women. These tattoos show off versions of womanhood that the fisherman accepts; the vixen, the whore, the siren, the martyr. Perhaps you could say that because these images are all tattoos, they are images that the fisherman has internalized. These images link together the place that women hold in the fisherman’s life. One tattoo is of a woman sitting in a martini glass, with a subtitle ‘Man’s Ruin.’ There is no subtlety to this worldview, and it aligns with the misogyny of Western culture. As long as the women in the fisherman’s life fall into these categories, as long as women fall into categories and are denied interiority and sense of self, they can be contained, just like the fisherman’s tattoos are contained in his skin.

After displaying the fisherman’s internalized concept of womanhood, Villadsen creates a scene for immediate contrast. The next image of a woman is the story of the infant’s mother; we see her boil water and return it to the sea, black as tar. And then, in one of the stranger sequences in the book, we see her have sex with a lighthouse. While the lighthouse has a clearly phallic nature, it is also clear that the woman’s pleasure is on her own terms, and excludes the fisherman and the type of masculinity he represents. At the end of the scene, the captive fish comments, “What a nice story,” which taken at face value seems strange. But in the context of the preceding visions of women vis-à-vis the fisherman’s tattoos, it is a vision of womanhood with sexual agency, a vision that defies the stereotypical image that the fisherman holds onto. It is a vision of a woman unrestrained.

This vision of womanhood oscillates between the fisherman’s vision of women and women as they actually are, and this thematic core is the heart of The Sea. When the fisherman tells the tale of his mother, the martyr, the child and fish refute him. Their consternation leads to him having a breakdown where he hides from the sea in a tiny room on the boat. Ultimately, the fisherman’s lie about who he is and what he can accomplish becomes overwhelming, as the sea wrecks his boat and he washes ashore, apparently dead. In that final moment, the woman, visibly pregnant, gives no thought to the corpse of the man in the sand. The birth of the child is coming soon. The child represents a new beginning, a casting aside of old things.

In her strange and lilting world, Villadsen uses the fisherman as a stand-in for a toxic masculinity seen all too often across the globe. The events of The Sea lay bare that toxicity and show its inherent worthlessness. Pride and boasting cannot steer a ship, and no amount of tattoos or pipe smoking can make a man a sailor. In this symbolism, Villadsen exposes the fraudulent nature of toxic masculinity. More precisely, not only is the fisherman a fraud, but his fraudulence leads to his demise. Dense with symbolism and surreal images, it is this confrontation that drives The Sea. Coupled with Villadsen’s vision of woman unfettered by man, the symbolic core of The Sea and Villadsen’s captivating illustration make it a powerful read.

This review was previously published by ComicsMNT.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply