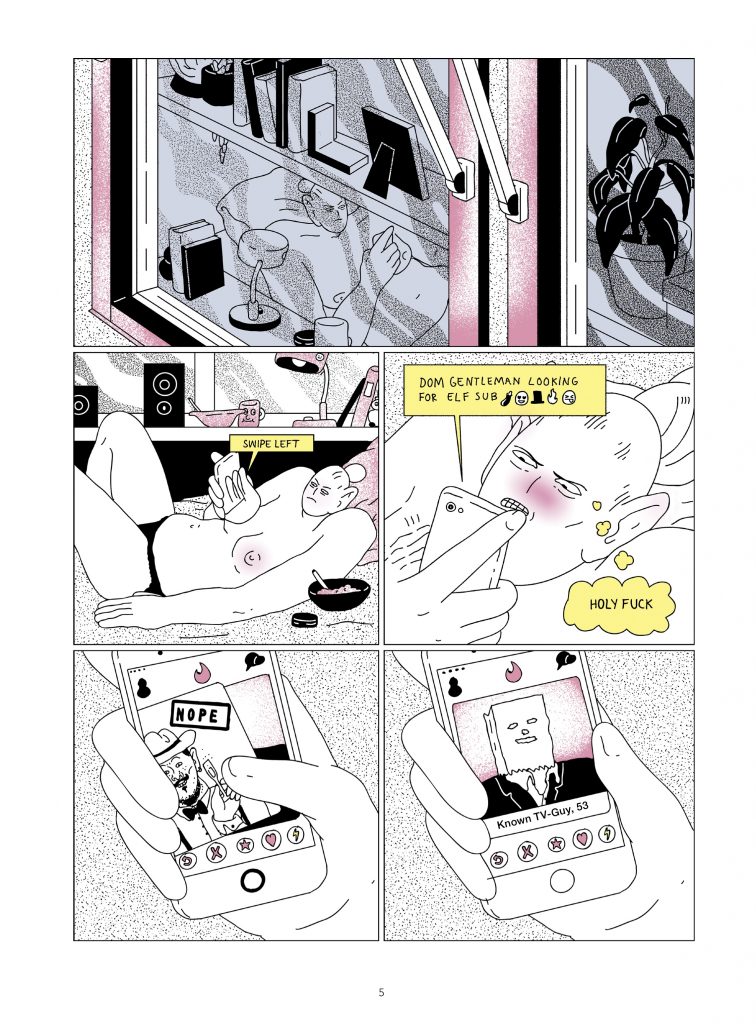

The introduction to Moa Romanova’s Goblin Girl is about as unflattering as you can get; readers are introduced to Moa lounging in bed amongst sheets and ashtrays, topless in black underwear, swiping left and right on random guys on Tinder, trying to find a match. Her face reddens with embarrassment and frustration and she reads a particularly heinous profile. Finally, she matches with a guy named “Known TV-Guy, 53” a man portrayed as a guy with a paper bag over his head. The scene ends with her scratching her pubes and continuing to swipe left on a bunch of unsuitable guys.

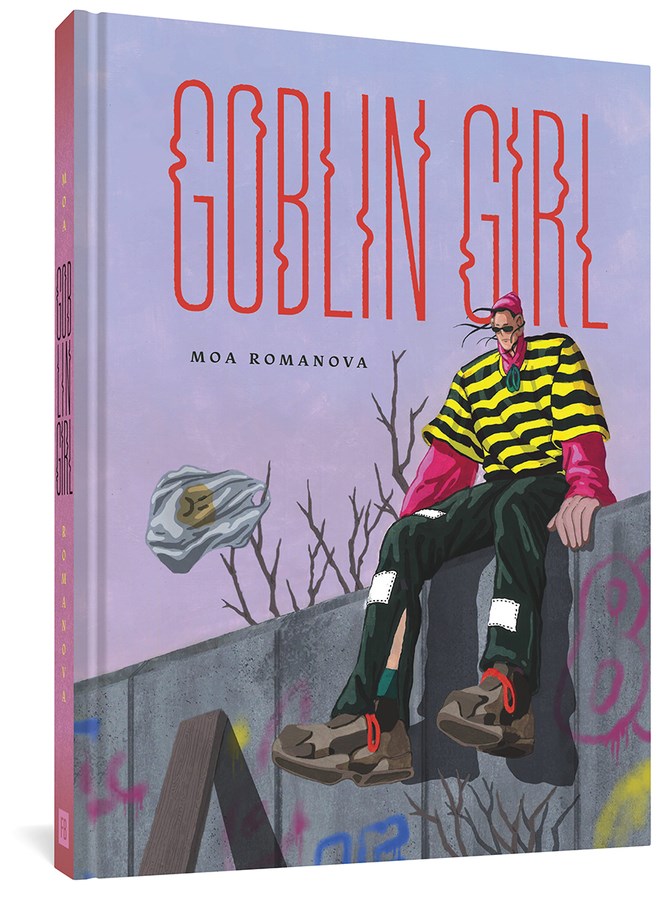

This unflattering introduction to Moa Romanova is characteristic of the entirety of Goblin Girl, a collection of semi-autobiographical comics recently published by Fantagraphics in the USA. Presented in a lovely hardcover edition, Goblin Girl details Romanova’s battle with anxiety and depression as a millennial artist trying to find her way in a complex and uncaring world.

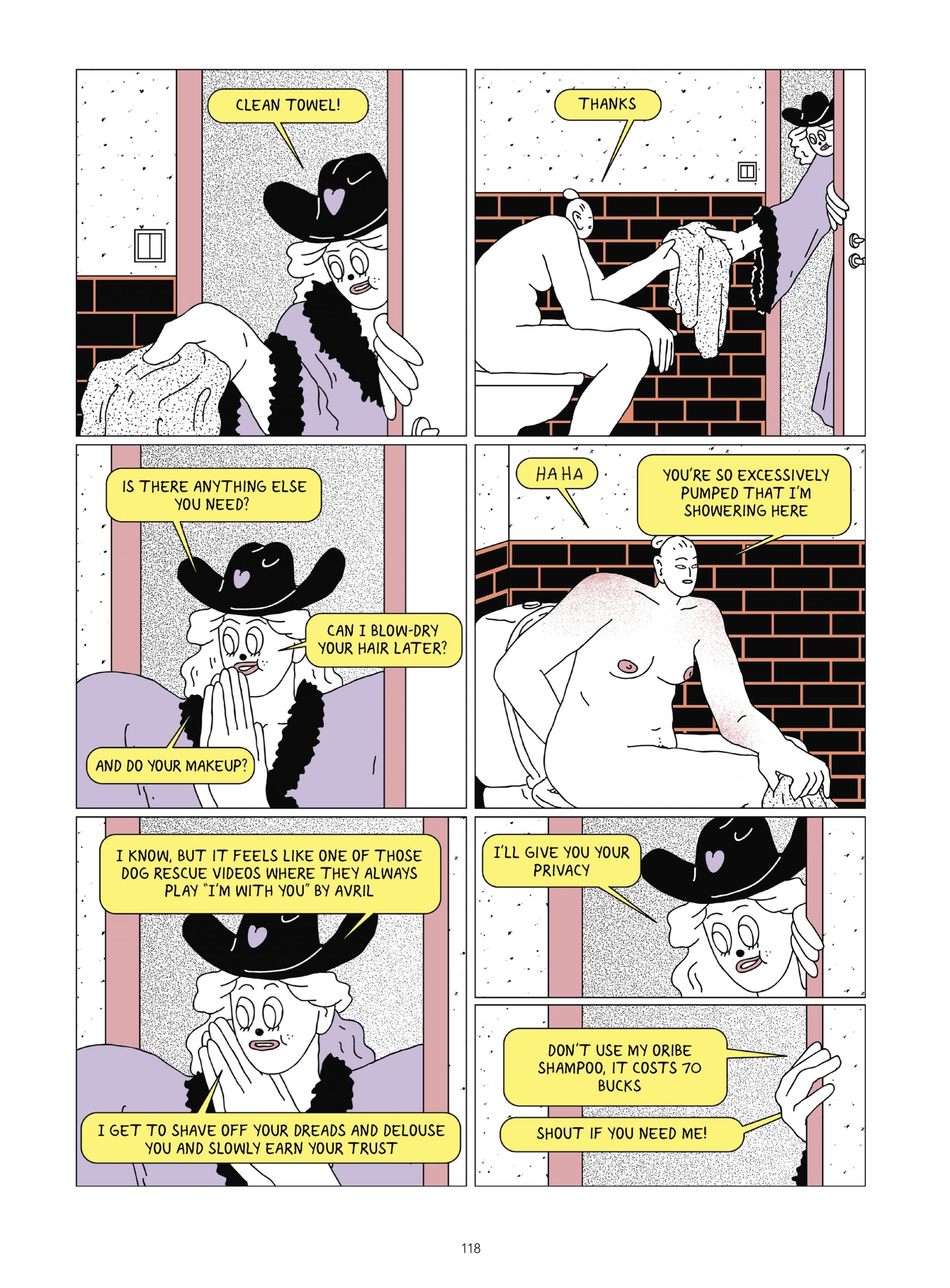

Romanova draws Goblin Girl in a style that’s both improvisational and technical. There are subtle details that make up the work, reminiscent of digital tools of bygone eras. Characters are drawn freehand over backgrounds that are often rendered as isometric projections, and backgrounds are littered with black flecking, a hallmark of spraypaint tools of programs like Windows ‘95 Paint. Her characters have large, physically dense bodies, overlaid on top of brittle appearing scenery. These large characters and spraypaint tones make the pages appear dusty and cluttered, filling up panels and overstimulating the reader. It’s appropriate that this effect happens in the book most when Romanova is in the midst of a panic attack; her face turning brighter and brighter red while the background crackles behind her like TV static. Still, what at first seems like nostalgia for old technology or “simpler times” is, in fact, a menacing buzzing that eats into Romanova’s space and emotional bandwidth.

Just as the anxiety that she battles on a day-to-day basis makes it harder for her to thrive, so too does Romanova find it difficult to connect with others. While Romanova draws her mother as a stylized Moominmamma, the very vision of comfort and care, Romanova doesn’t even have the energy to be present with her when she goes to visit. Her friends seem like they’re talking in other languages (at one point, actual hieroglyphics appear in a speech bubble), and Romanova seems to only find comfort in an internet stranger who wants to get into her pants. “Known TV-Guy, 53” is a well-off artist and TV personality who pursues Romanova after matching on Tinder. When she freaks out because of his clingy behavior, he eventually offers to be a patron of her art, hands-off. This relationship is strange and exploitative, and it’s clear that “Known TV-Guy, 53” is still trying to groom Romanova for a relationship despite saying he just wants to help her make her art.

All of this is portrayed in stark detail, and, in fact, the confessional nature of Goblin Girl doesn’t portray Moa Romanova in the best light. She illustrates herself as a mess, unable to keep her apartment clean or be present with her friends and family. Yet, the point is that Goblin Girl is very specifically not trying to paint Romanova in a positive way; instead, it is disarming in its openness. This creative choice puts Romanova into a lineage of female cartoonists making raw, confessional work, including masters like Julie Doucet and Ariel Bordeaux.

Still, all of this emotional baggage and deliberately claustrophobic art are cut with Romanova’s sardonic wit; this book is at times exquisitely funny, and, at others, gut-wrenching. Watching Romanova’s friends make fun of an undercover cop at a rave is a laugh-out-loud moment, and it’s immediately followed by a scene of her pissing in an alley and becoming increasingly panicked as her friends take drugs and she stays sober.

What elevates Goblin Girl is the mix of these two extremes. It is to her credit that Romanova successfully threads the needle, never falling too far into maudlin tears or bitter teeth-grinding. There’s a pulsation to the work, an up and down that feels tidal, almost inevitable. But Romanova steers Goblin Girl through these waves successfully. The emotional journey that she progresses through in Goblin Girl to accept herself and learn to deal with her anxiety feels appropriately earned. This is a stellar debut; Moa Romanova is a talent to watch.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply