Contradictory as it no doubt sounds, when a reader goes into an Eric Haven book, they know what to expect in a general sense — but they never know what to expect on any given page. And it’s that delicate balancing act that makes Haven’s work uniformly interesting and the unmistakable product of what can only be fairly termed as a very singular artistic sensibility.

After a long-running gig as an executive producer on TV’s MythBusters necessitated a cartooning hiatus, Haven has been reasonably prolific in recent years, and he’s refining his technique and tightening his narrative and thematic focus with each successive project. While he may not, then, be actively challenging himself to do something different from one book to the next, he’s clearly challenging himself to improve the type of comic that he makes, and at this point, it’s probably fair to say that he’s developed something of a genre unto himself: the hermetically-sealed “story cycle.”

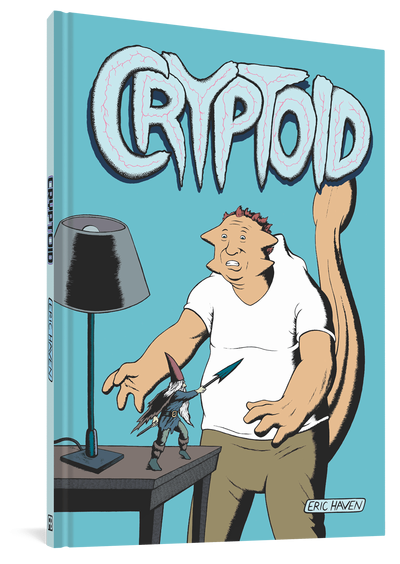

Haven has done this by (nearly) perfecting the art of the transition; each of his stories has discrete beginnings, middles, and endings of their own. Haven then strings these together by means of a fluid narrative “connecting tissue” before he finally, more or less, drops us off back where we started, albeit in a manner that not only fleshes out where we are/were, but where he’s taken us along the way. His latest, Cryptoid (just released from Fantagraphics), essentially follows this template established in his earlier “graphic novella” Vague Tales, albeit with a constantly-running “creature theme” and more of a “macro,” or “big-picture” focus. Whereas Vague Tales was possibly the product of one protagonist’s troubled mind (keyword there being “possibly”), in Cryptoid a type of cosmic “watcher” figure looms large over the proceedings — although that doesn’t preclude the vignettes we’re privy to from being entirely imagined by the especially bizarre and semi-tragic prehistoric monster/human hybrid pictured on the cover. But to say more about that, as the old adage goes, might be to say too much.

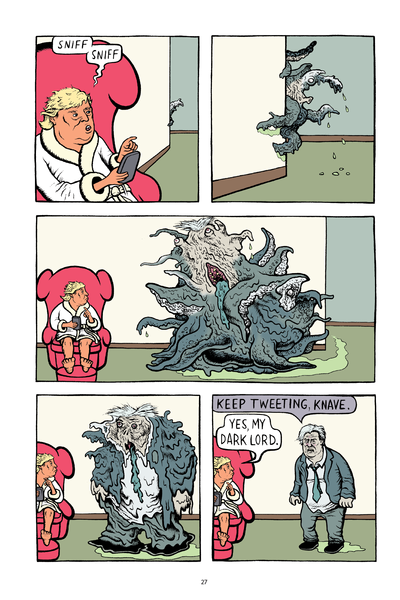

Certainly the clean lines and crisp colors that Haven utilizes do more of the “heavy lifting” here than does his intentionally-minimalist dialogue and “old school” sound effects (the book takes far longer to look at than it does to read), but that’s all well and good given that his Fletcher Hanks-influenced art is more than up to the task. It’s the “far out” subject matter and moral absolutism that Haven trades in that is even more reminiscent of Hanks than the illustration, though, as his heroes and villains tend to embody forces of either pure and incorruptible good, or malevolent and completely corrupt evil. This leads to some seriously funny stuff, like an anthropomorphic female bald eagle called “The Resister” who perches herself atop the Washington monument puking her guts out all over Donald Trump, but it doesn’t negate the notion of subtlety or nuance completely, even if you’ve gotta work to find it.

Fear not, though, I have some advice as to how to best go about doing just that, namely: relax and go with the flow.

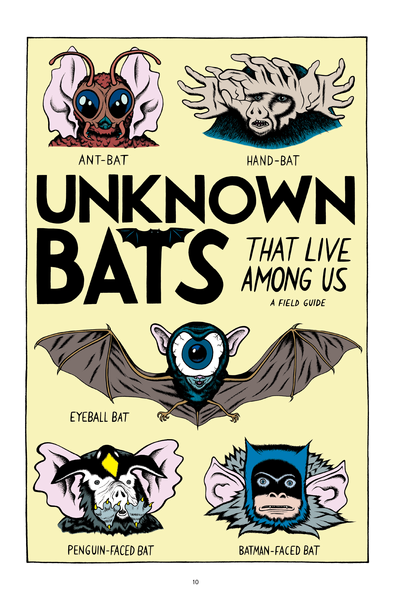

As Haven shifts from one short-form “creature feature” to another, a consistent mood is, against all odds, sustained throughout Cryptoid: part surreal, part absurd, part slapstick. It’s a unique amalgamation of elements, to be sure, and also a surprisingly lively one given the deadpan omniscient point of view they’re all presented from. One could imagine any of these pages being saturated with the kind of overly-expository narration that Hanks (there’s that name again) and his fellow “Golden Age” contemporaries made their stock in trade in the early days of the comics medium, but it’s to Haven’s credit that he only borrows elements of the temperament and aesthetic rather than going the dull and unimaginative route of the pure homage. To put it in more stark terms, there is very little here that one could call blatantly cynical, but that absence of cynicism in no respect means that what Haven has crafted is in any way immature, much less outright naive.

And it’s that absence of naivete that gives Haven the freedom to trade in the outrageous and ridiculous without the worry of coming across as being cloying or too precious for his own good. It’s true that there’s absolutely crazy stuff depicted in almost every panel of this book, but it’s taken as a given: this is his world, these are the rules he plays by, and while it’s too reductive to say you just treat the outlandish as a matter of course here, it’s nevertheless true at the same time. It also means that the trajectory of the work has a definite and easily-discernible progression, but it’s more circular, even elliptical, than it is linear. This is challenging and exciting and all that good stuff, sure, but it also feels incredibly naturalistic, as if these apparently-disparate events were meant to happen in a very precise “running order,” to refer back to each other, even to build upon one another — but in a manner that adds breadth, depth, and understanding to where we were at the start every bit as much as it does to where we are at the loosely-defined “end.” And thank goodness for that since it is, after all, the same place — more or less.

There’s room for a lot within this self-contained world/universe/reality, from mischievous garden gnomes to authorial doppelgangers, but, at the end of the day, what’s most interesting about Cryptoid is its singularity, insularity, and internally-consistent logic, tone, and aesthetic. The term auteur is perhaps overused today, but, in this case, it certainly applies: there’s no mistaking an Eric Haven comic for a comic made by anyone else, and even if his work largely amounts to variations on a theme, it’s a theme that stands up to constant and further exploration, definition, and expansion.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply