There are many things you need to know about rising star Emma Hunsinger. Despite still being in her twenties, she’s having the kind of career that most cartoonists only dream about. For instance, she just had a ten-page spread published in The New Yorker (yes, ten pages, longer than any comic in the history of the magazine). There are agents and editors swirling around her. She’s had offers for books and anthologies. And she’s in the midst of finishing her second year at The Center for Cartoon Studies, where her thesis adviser is none other than Tillie Walden, one of the most successful artists to graduate from the school.

But here’s something else you need to know about Emma Hunsinger: she’s really, really cool. She’s as self-deprecatingly funny and intuitively bright as her comics. As Emma and I talked over breakfast, I found myself wanting to hear about her process of making comics as well as also wanting to plan for a road trip like we were best pals.

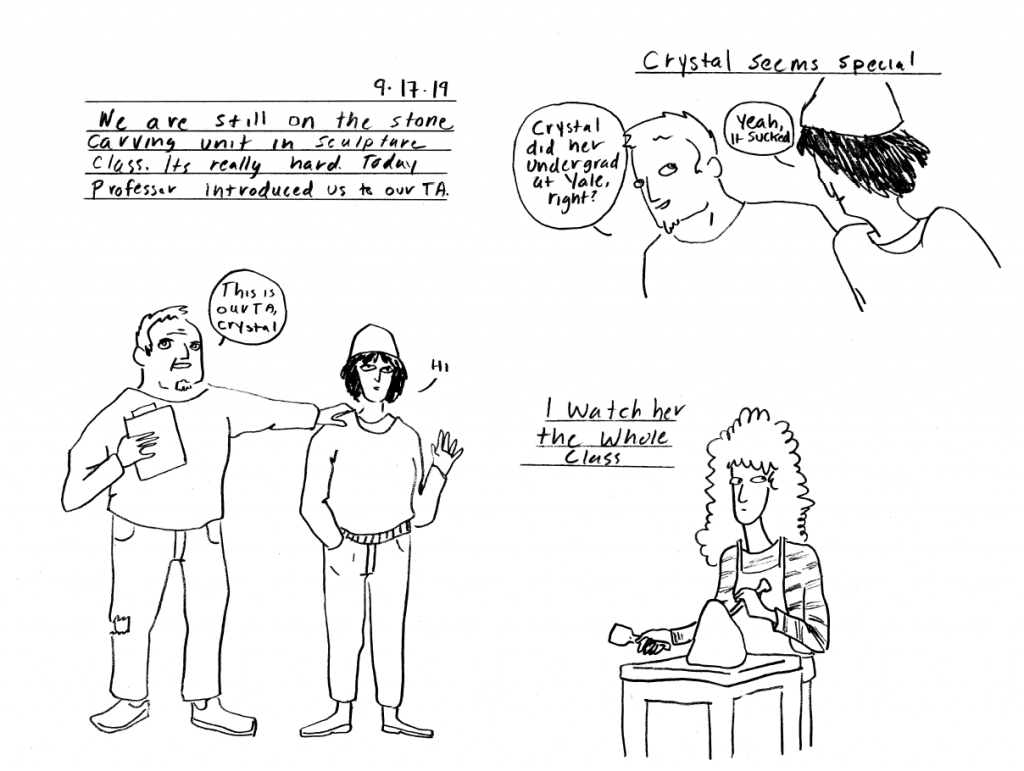

If you haven’t read Emma’s breakthrough New Yorker cartoon, “How To Draw a Horse” it’s about a young girl’s fascination with drawing horses and using that to get closer to another girl in her class. It’s awkward and honest but also hilarious. Her first-year, “mini-thesis” project at CCS was a comic called “Chunk,” which Rob Clough listed as one of his favorites of the decade. In “Chunk,” Hunsinger follows a group of art students in a sculpture class who fall in love, fall out of love, and come to terms with life and its lessons. Plus, it somehow manages to include several pages of a sex fantasy with Wonder Woman. In other words, it’s amazing.

Here’s something else to know about Emma: she has wanted to do this her entire life. While other kids dreamed of being astronauts and professional baseball players, Emma told her teachers that she wanted to write comics for The New Yorker, which makes all this early (and deserving) success even more thrilling to those of us who are her classmates at CCS.

Emil Wilson (EW): I’m going to start off with a big question to get the ball rolling. Are you an artist who writes, a writer who draws, or neither?

Emma Hunsinger (EH): It’s funny because I feel like I talk about this a lot. I know what my drawings look like and I know I’m not the best artist in the world. But I also know I’m not the worst. I’ve never been interested in writing prose or poetry. So I guess the answer by default is neither. That’s what I love about comics. It’s like tricking people into thinking you’re really talented, when your real talent is knowing how to combine a lot of things you’re sort of good at to make something greater than the sum of its parts. I think if you typed out all the text in my comics it would read like histrionic high school poetry.

EW: Okay, so then what are the things you’re good at when it comes to making comics?

EH: Having fun, especially when I’m drawing. I make myself laugh when I draw. It’s happened a few times in the (senior art) studio. I’m in the first room and the people in the other room will hear me giggling and I’m all by myself because I’m drawing something that’s making me laugh. It’s a problem too, though; if I draw something I really like I stand up cause I’m so excited, and then once I’m up I usually get distracted.

EW: What makes you laugh?

EH: I really laugh when I find a good way to hide something in a drawing. It’s rare but it has a high payoff. My favorite thing to do when I was regularly submitting New Yorker cartoons was to draw posters for things in the background of the cartoon. I keep drawing people in the dermatologists office so I can put in a poster for “lumps and bumps.”

EW: Tell me about your background and what led you to comics.

EH: I always wanted to be a cartoonist: I submitted my first cartoon to the New Yorker when I was 12. We had this project in seventh grade where you have to do a history of yourself and what you expected of your future self. I wrote that I wanted to sell cartoons to The New Yorker BEFORE I got to high school; I gave myself one year to start selling gag cartoons to The New Yorker.

I got into comics freshman year of high school: my history teacher was new to the school and was very enthusiastically starting a “Graphic Novels Club.” I didn’t know what a graphic novel was and was really curious, but also terrified of doing anything that could be perceived as ‘uncool’ so I didn’t join. Then one day he caught me drawing a worksheet in class and told me in front of all the lacrosse boys that I should come to the Graphic Novels Club. I was mortified but the whole thing somehow fueled the fire and I was desperate to actually see what a graphic novel was.

The teacher helped start a graphic novel section in the school’s library that I was, of course, too terrified to look at, lest someone think I was a nerd or something. I went in during lunch one day when the library was sort of empty and I could finally look at the graphic novels section without being seen. I decided that when I had the chance, I would check out this one graphic novel called Blankets by Craig Thompson.

Of this whole story, this is the thing I remember the most vividly: Right before Christmas break I was in the library with the basketball team (I was on the JV basketball team) and I knew I could NOT wait another week. So I went and grabbed Blankets off the shelf, checked it out, and HID IT UNDER MY SWEATSHIRT, so that none of the basketball girls would ask me about it and slipped it into my backpack.

I literally could not wait to read this book. That night we had to go to a Christmas party and I didn’t care. I sat on the couch at our friend’s house the entire time and read Blankets. I’d never been so into anything in my life. I swear I couldn’t hear anything around me. I was getting my world rocked by this book. I had never seen anything like it. I read every graphic novel in the school’s library, and when I finished that, read almost every one at the public library over the course of my next four years in high school.

EW: How does it feel now that you’ve accomplished getting work into The New Yorker and fulfilling your seventh-grade dream?

EH: It’s so anticlimactic. I wanted this for so long and, when I finally got the copy of the magazine, I was standing alone in my apartment and there was my name in The New Yorker and I thought Okay, I did it. Then I just put it on a shelf and haven’t looked at it since. You work so hard before you get there. Before I sold a cartoon I submitted maybe hundreds of cartoons. I learned a lot of lessons that have really served me. The best lesson was how to get rejected. They’d say that I was close, but no. Or there’d be radio silence. The New Yorker gets a thousand cartoons a week, so they can’t respond to everyone who submits. But getting rejected helped me understand why I’m doing this. I’m not doing this because I want to have the most cartoons in The New Yorker. I’m doing this because I have ideas that are fun. I also learned a good lesson about the editors’ tastes. There are some cartoons that The New Yorker simply can’t accept. You could craft the perfect joke; millions and millions of people will love this joke and it’ll be one of the greatest gags ever, but if a majority of The New Yorker audience won’t understand it, then the magazine won’t buy it. I learned to not take that personally. That editors have a job to do and their rejection doesn’t say you’re no good, it mostly says “it’s not right for us.”

With “How to Draw a Horse” in the magazine it’s like, what more could I want? I’ve stopped thinking about material goals like selling a book (though I would love to sell a book). What’s important to me is to keep making work that’s good. A lot of people said a lot of really nice things about “How to Draw a Horse” and I set the bar really high for myself.

EW: How does that affect your thesis and the work you’re doing right now?

EH: For my thesis it became pretty clear right off the bat that this would be a good time to discover then hone my process. Before CCS, I was doing gags and no long-form stuff at all, so I’ve taken this year to figure out how I work. And that’s been what’s really important. I’m trying not to think about career moves and focus instead on how I get the best work out of myself.

EW: And what have you discovered?

EH: I’m trying to best figure out how to get unstuck. I’m writing this little comic and I keep getting miserably stuck in the story. I learned it’s really important that when I get stuck I need to stop working and do something else. Right now, my hobbies are walking or taking a shower or lying down and thinking. Sometimes I walk to the gas station and treat myself to a Gatorade or some gum. Every now and then I will drink one beer and play Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons really loud. Going to the movies helps too. These are my hobbies for real, I’m what you would call “very boring.” I mean, I’m a fun person but I don’t do much; I’ll probably develop more of a life after I graduate.

EW: How would you describe your work?

EH: My work is over-dramatic, but it isn’t totally nauseating because it’s also pretty silly. My dad always says “you can pretend to be serious, but you can’t pretend to be funny.” It’s one of his dad-sayings (every dad has them), so I heard it a lot and it really made me think about the relationship between serious and funny. I think for me, in my work, to make something really emotional there has to be a balanced amount of foolishness. It’s how life is and so it makes things more real.

EW: What’s it been like coming out through your comics?

EH: That’s a good question, especially since I never had a real coming out. I eked out of the closet. When my comic got published, it was when a lot of people in my life found out I was gay. Looking back, it was a great way to do it. I don’t like coming out. I’m a little bit straight-passing cause I have long hair. But it’s been a relief for me because I don’t have to explain myself; you can just read it. It feels okay to be open and vulnerable in my work and that’s the stuff I love to read anyway. And it seems to be the work that other people enjoy reading too.

EW: Who influences you?

EH: Casey Nowak’s Diana’s Electric Tongue. That was one of the first comics I read that got me really excited. That story felt like A STORY. I love Eleanor Davis. I love Mickey Zacchilli because her work is so wild and so evocative and it always makes me laugh. I took a class from Patrick Crotty at the RisoLAB at SVA. I love his work. Freddy Carrasco and his book Hot Summer Nights. Carta Monir on ZEAL had this comic called Lara Croft is my Family and that paved the way for “How to Draw a Horse.” In that comic, she talks about family vocabulary and it was so similar to the experience with my family. It made me realize that if you can pinpoint these little, little moments that happen to everybody but are hard to describe, then it’s really beautiful for a reader to see it. I just got Disa Wallander’s new book; I would like my work to be as delightful as hers.

EW: What would you do if you weren’t making comics?

I’ve been asked that question before and before I answer it, I need to get more specifics on the scenario. Do I have all the talent and ideas that I have now or am I a totally different person?

EW: You have all the talents you have now. But you can’t make comics.

EH: I’m not letting myself?

EW: They outlaw you. You’re banned from comics. You have to go find other work.

EH: (laughs) Oh okay. Wow. I’m going to assume then that I’m miserable. So then I’d be a mailman. Lately I’ve been craving stability almost more than anything, and people will always need the postal system, so there’s security in that. I also love walking and uniforms. I’m boring, remember? Being a mailman would keep me baseline happy while I was outlawed from comics.

EW: Tell me about your experience with The Center for Cartoon Studies. What brought you here?

EH: I was technically a professional cartoonist selling work to The New Yorker, but I felt my cartoons didn’t look very professional. I was really frustrated with my art and felt like I didn’t know what I was doing. I wanted to be better. I had the opportunity to come here, which has been huge. I’d never been a good student before I got here. I have almost no attention span, but then I came here and got to do this thing that I’m crazy about and I became a great student.

I was happy to get out of New York. And it was so nice to be around people who were doing this. Everyone in my class is doing really different work and everyone has such different goals. But we’re linked by this drive to be cartoonists. I loved my first year here. I loved rising to the occasion. I have a really special, fun, interesting group of people in my class. I couldn’t have done “How to Draw a Horse” without them. For my big assignment at the end of the first year, I did “Chunk,” which was super informative for me. First, because I didn’t use panels and the whole thing felt really different. At the time, I was working at a local print shop, so I was printing stuff for other people and it had to look really professional. I got a lot of insights about how I wanted “Chunk” to look. I knew I wanted it perfect-bound and that I wanted it to be 300 pages, which looking back now was crazy. I ended up settling for 112 pages, which is still a lot.

EW: And how’s the second year? What’s it like working on your thesis with Tillie Walden?

EH: For the second year, the big difference is that it’s all on you. At CCS, you get out what you put in. The first year, I pushed my limits and went all in. I took a lot of opportunities. For the second year, you have to set your schedule yourself. I’m lucky that my schedule is flexible so I can pour a lot of time into my thesis. I love working with an advisor and working with Tillie is amazing. I think Tillie and I are a really good fit. I asked for her because over the summer I was getting a lot of attention from Middle-Grade publishers and I was thinking about writing for young people which Tillie does exceptionally well; plus she had gone to the school herself, which is an advantage when picking an advisor because they know what’s expected of you and such. I’m so glad she said yes, I’ve had the best time working with her.

Tillie gave a Visiting Artist lecture last year and she talked about her process and working spontaneously. I work that way too. Lately, I’ve been thinking about the feedback process. I can imagine a version of myself that doesn’t want to take advice from anyone, but there’s been work that I’ve shown Tillie, and she’ll point out things to pay attention to and it’s incredibly helpful. It takes a while to trust other people to know what’s best with your work. But Tillie has made my work so much better.

EW: When you think about your craziest dreams for the future, what comes to mind?

EH: I have this nonsense dream of being the writer on The L Word. I don’t know why, I never even watched the original. I just feel like I’d enjoy it. If there were a way to be a mailman and a cartoonist, you know I’d do that.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply