So much of the experience of art is what you bring to it. I know that, as a teacher, nearly every time I sit down to approach a novel I’ve taught before, I find some new perspective in it that arises out of either my current understanding of the world or the dynamics of the student group to whom I will be teaching it. Art thrives in its ability to mutate and reflect back upon its audience that which they need at the time.

Sometimes, though, you return to a work, especially one that had a particular meaning for you in years past, and, through your present self, all you see are its flaws. The disconnect between the work’s importance and its disappointments can be jarring, and it might possibly make you reevaluate your original experience entirely, leading to some sort of existential crisis or just a profound sadness. This disconnect is at the heart of Victor Martins’ Cabra Cabra, the new issue from Kevin Czap’s and L. Nichols’ Ley Lines series.

With a fluid line and a unique sense of pacing and layout, Martins uses their tools as a cartoonist in Cabra Cabra to convey the disappointment and anger they felt upon rereading Orlando by Virginia Woolf, a foundational work of literature for them in their journey to self-discovery. It’s a tricky bit of business, for sure, walking the line between acknowledgment and ire, but Martins is able to balance on this tightrope sturdily enough to fully convey their ability to accept both their disillusionment in and their gratitude for the work as they read it today.

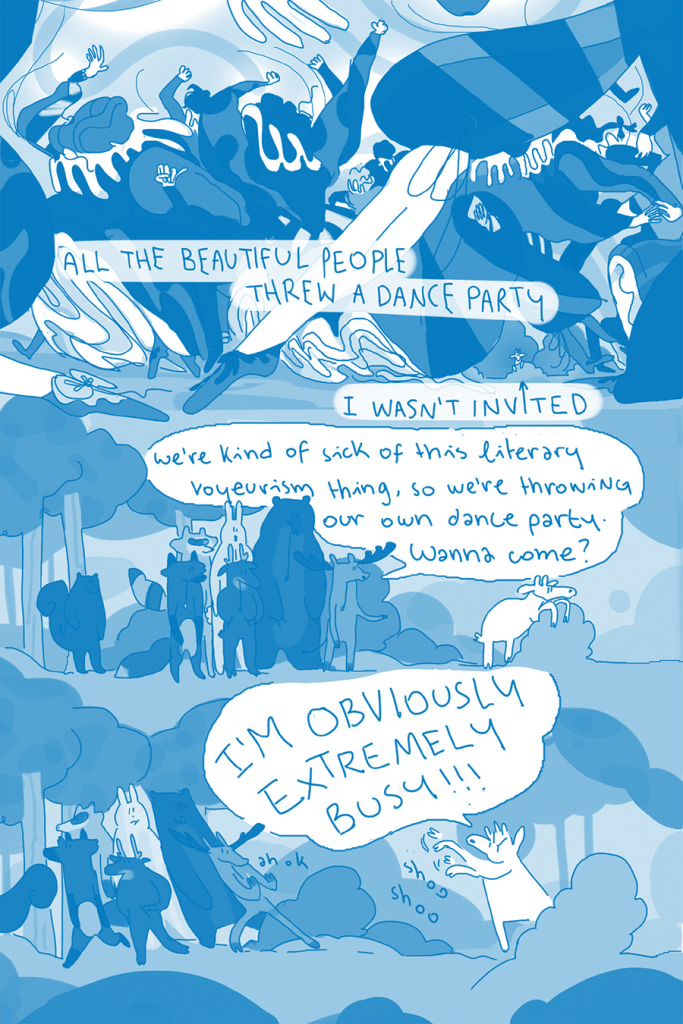

Cabra Cabra starts off as a rather plaintive rant; nearly two-thirds of its blue-inked, risographed pages are focused on Martins’ escalating fury directed towards Woolf’s blatant racism in Orlando. Martins uses an increasingly frenetic cartooning style to build this emotional heat, dispensing with panels entirely on a few pages, and allowing their lettering to dominate the work. This approach is meant to be loud, and it reverberates off the page. In the remaining pages, though, through the very clever use of a narrative twist, Martins both slows down the pace of the book and quiets it significantly. Martins indicates an understanding that they come to, reveling in the importance of the artistic moment, and conveying the significance and weight of finding work that speaks directly to its audience in ways they might otherwise have never heard. It is this concept of being seen that brings about the unfettered joy that Martins so beautifully communicates at the end of their work.

And it is this joy and the circumstances that surround it that elevates Cabra Cabra from a soapbox bloviation to something special and heartfelt and necessary.

Cabra Cabra is an example of what makes comics such a unique medium. Through Martins’ skills as a cartoonist, they are able to communicate that which is simultaneously an intellectual and emotional moment in a format that forces the audience to follow that very journey of understanding. It is as if Cabra Cabra is concurrently a poem, a diary entry, a work of visual art, and a dance. In its brevity, it finds weight. In its fluidity, it finds solid ground. In its art, it identifies and celebrates.

As Martins says at the end of their book, “It’s ok to move past things you loved. It’s okay to want to feel seen. It’s ok to expect better.” But they also acknowledge that “this racist white lady’s racist book will never not have been important to you.” And it’s in this final understanding, this acknowledgment, this truth, that Cabra Cabra opens up fully, takes its deep breath, and dances. It’s hard not to love this exquisite work of art.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply