It’s always a tricky task to review a work when it’s still ongoing, but good is good and bad is bad, and while it’s considered poor form to give away the game so early, there’s absolutely no doubt that cartoonist Colin Lidston’s The Age Of Elves (Paper Rocket Minicomics, ongoing) is very good. It’s also richly deserving of far more press attention than it’s received so far, and so I’m hoping to do my bit to address that glaring oversight by, yes, reviewing it before it’s finished. And, frankly, it’s so damn enjoyable that I hope it’s a long way from being finished.

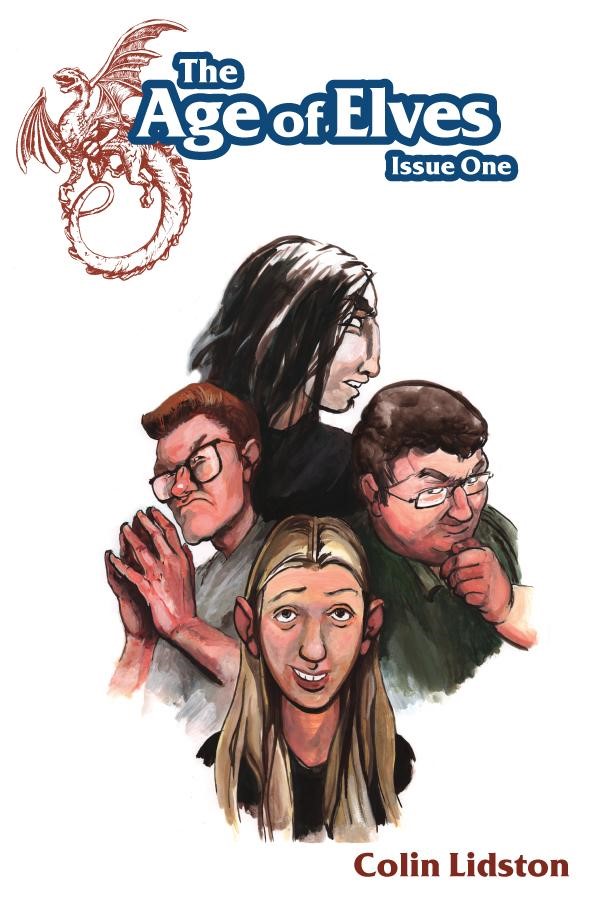

The premise of this roughly-annually-published series is simple enough: teens Sarah, Jamie, Bram, and Evan are a tight-knit group of hard-core tabletop/role-playing gamers, but their “geek culture” interests range far and wide (one of the best scenes in any of the four issues to date comes in #1 when the group gets in a heated, but good-natured, debate about what was actually in the suitcase in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction), and they’re all living for their trip to GenCon, the world’s largest gaming convention. For Sarah, who Lidston casts in the role of the audience’s eyes and ears, the trip has an additional level of “make-or-break” importance: she has dreams of becoming a fantasy illustrator and hopes to both meet and pass samples of art to Rachel Canty, her idol in the field.

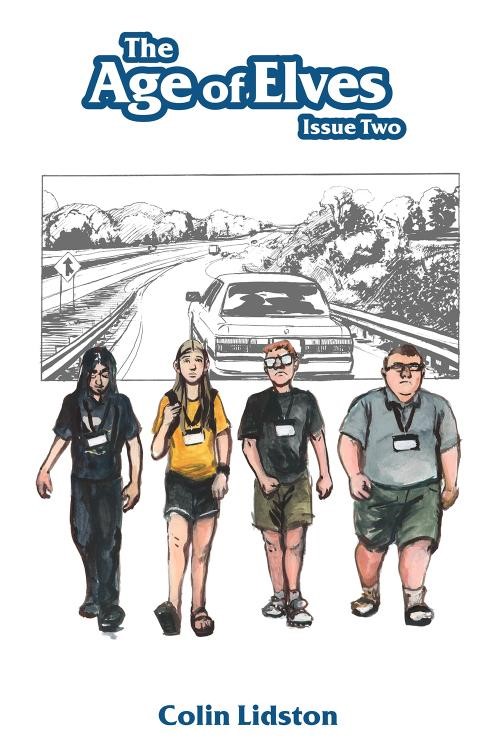

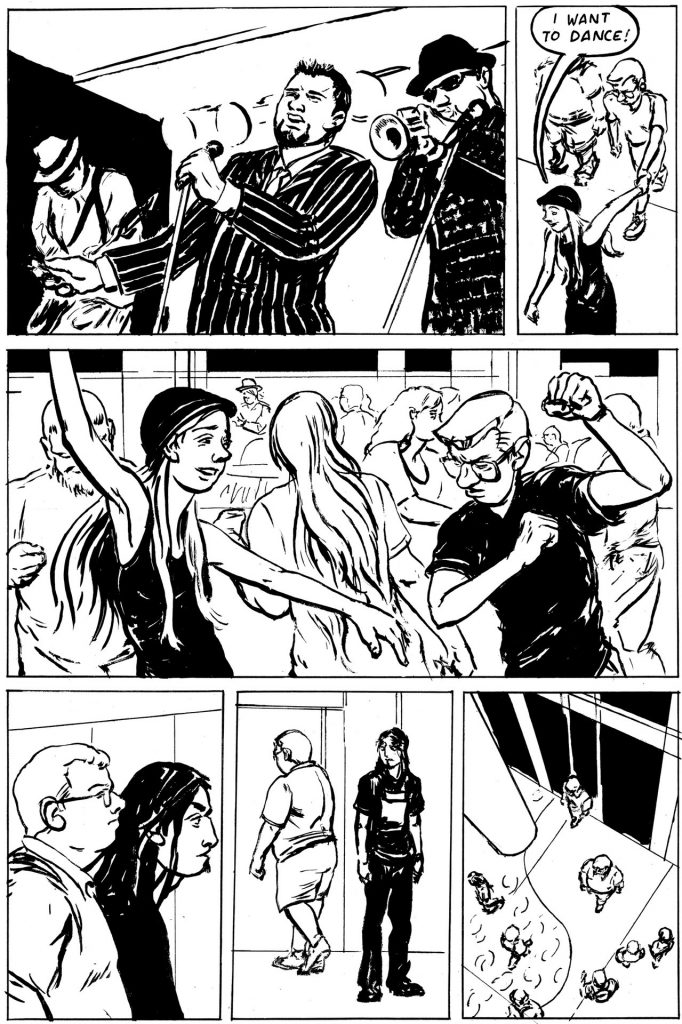

Spoiler alert — they do, in fact, make it to GenCon (most of issue two takes place entirely in the close quarters of the Honda Civic they use for their road trip), and, so far, half the series has taken place there, showing the highs, lows, and in-betweens of what happens when a group of largely-sheltered young folks finds themselves in, if you’ll forgive the term, “nerd heaven.” On the plus side for our quartet, they finally get to meet geeks other than themselves — on the minus side, well, they finally get to meet geeks other than themselves. And said “other geeks” all seem to have about ten years on them, at least. While there’s some mild interpersonal drama within the group, it’s their wide-eyed exposure to an even wider (and wilder) world that is the main focus here, and Lidston’s uncanny ability to channel exuberance and reluctance in equal measure, with an appropriately “brave face” front for social purposes (“act like you’ve been there before,” as the saying goes — even if you haven’t), has an air of genuine lived experience to it. He is, therefore, either channeling some of his own memories here or so damn good at faking it that he may as well be.

By way of full disclosure, I should make it plain that gaming and fantasy art are not only things I’ve never been into, and I have no real interest in them to this day — but I can’t help but find these kids almost immediately relatable. Their late-night gaming campaigns, fueled by pizza and Mountain Dew; their fight-to-the-death arguments over the most pointless minutiae of various fictional “universes” before making up and being best friends again five minutes later; their pinching pennies earned at shit gigs to go and have the best weekend of their lives — there was a time when the “cool” cartoonists would have laughed at all this and treated it with disdain, but Lidston shows the unique social “glue” that comes from being the only outcasts in town with something less than romanticism, but something far more brave and honest than mere “gawk at the losers” cynicism. No cheap and easy targets here — only real people.

Still, sharp as his dialogue is, realistic as his characterization is, and simple-yet-gripping as his plotting is, it would all be for naught if the art wasn’t up to the task of being appropriately communicative. Fortunately, though, there’s no need to worry on that score — this is strong cartooning with plenty of personality. Realistically-rendered bodies and faces, expert use of varying line weights, and smooth expression of motion are just some of the tools in Lidston’s bag, but they serve him every bit as well as a full supply of arrows in the backpack (or whatever it’s called, my ignorance is showing) of a Dungeons & Dragons archer. It’s mildly stylish stuff, especially when it comes to his use of rich and inky blacks, but, by and large, it concerns itself with being functional above all, and that makes all the difference in the world. Sarah, for instance, may not necessarily verbalize what she’s thinking as she strikes up a tentative friendship with an older LARPer couple, but her face always clues readers into what’s happening inside her head.

The subtexts running throughout here aren’t just artistic, they’re also narrative — what happens when you get to the nearest thing you have to a holy land? In what ways does it measure up to your dreams or expectations, and in what ways does it fall short? Is this the last hurrah for this group of friends, or do the middle-aged cosplayers offer a glimpse of their own futures? If so, is that what they want — to the extent that they even know? All of these characters are fairly well-centered in terms of knowing who they are, but is who they are who they want to be? And how do they close that gap if it’s not? Adolescence is a years-long crossroads almost by definition, of course, but in The Age Of Elves, Colin Lidston reminds us that there’s so much wonder and freedom inherent in life’s transitory phases that we’d all do well to cleave to at least some of that mindset throughout our lives. We are all capable of being or becoming whoever we choose to be — even if that’s a mystical warrior princess for five or six hours on a Saturday night. And while it’s perfectly fair to say that it mines similar thematic territory to that of Netflix’s Stranger Things and Kieron Gillen and Stephanie Hans’ Die from Image Comics, the crucial distinction is that in those works, the characters find their purpose (and, in some cases, their redemption) only when their fantasy worlds literally become reality — Lidston’s approach is both more honest and more revealing, in that he demonstrates what happens when people’s fantasy lives shape and inform their reality. It’s extraordinary stuff and is shaping up to be one of the most unique “coming of age” narratives the comics medium has seen in quite some time.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply