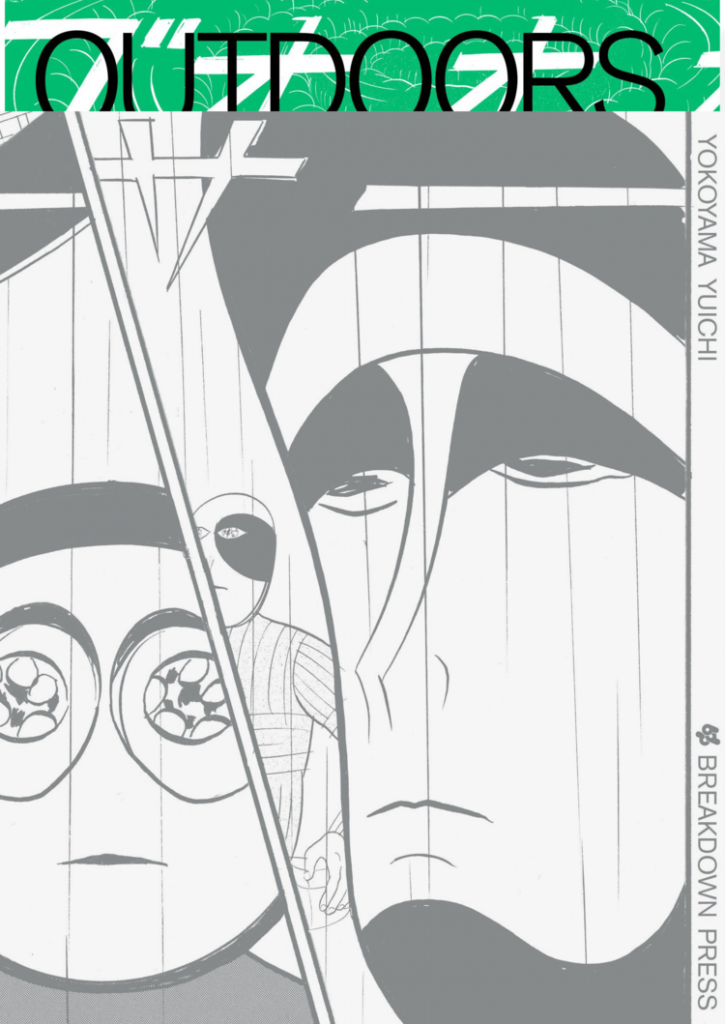

Innovative to the point it borders on being mysterious, the work of “neo-manga” auteur Yuichi Yokoyama never fails to impress precisely because it’s nevertheless eminently approachable, even inviting — and while his latest work to be translated into English by Ryan Holmberg (who also interviews Yokoyama for the book’s engrossing “backmatter” section), Outdoors (2019, Breakdown Press; original Japanese publication date 2009), is considered something of a less-than-essential, “smaller” entry in his lengthy oeuvre by some scholars of the medium, it’s still a fine example in microcosm of his recurring themes and concerns, as well as a worthy-enough subject of study and analysis in its own right. It may not enjoy the trailblazing reputation of Travel or Iceland, it is true, but its welcome (to say nothing of long-overdue) re-issue for Western audiences will hopefully go some way toward burnishing its bona fides as something well beyond a “stop-gap” project situated between more purportedly “major” works.

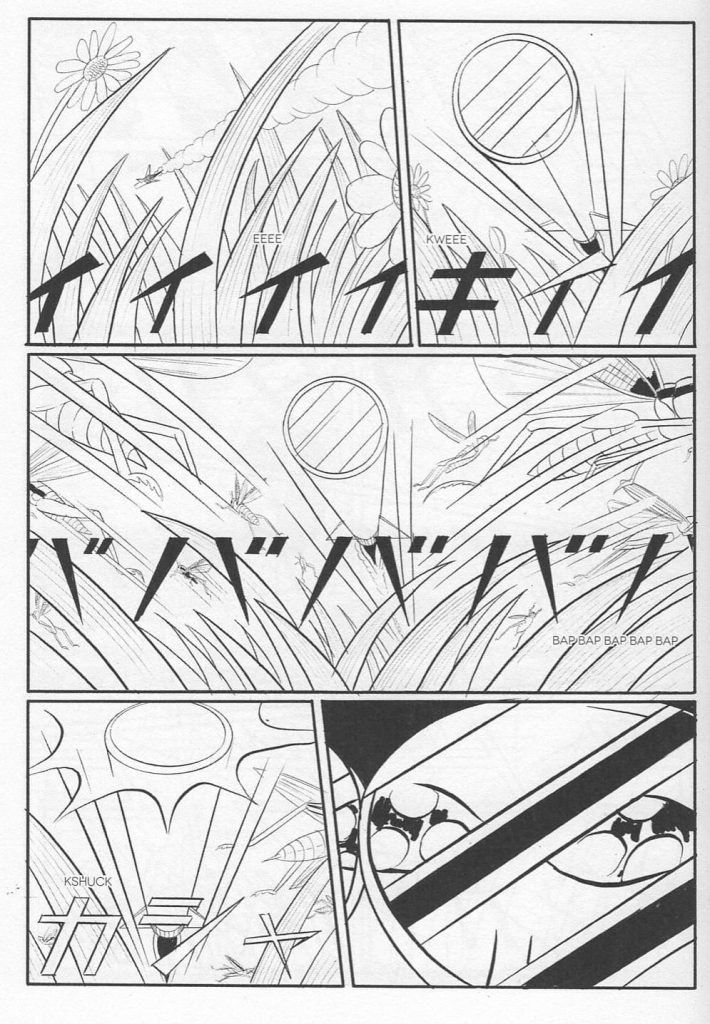

Granted, if you’re new to Yokoyama this may not, in all fairness, represent the best place to get started, but it’s by no means a “bad” one, either. As a matter of fact, one might reasonably contend that this trilogy of thematically-linked short stories (simply titled 1, 2, and 3) offers first-time readers a chance to reflect upon and absorb the marvels and wonders of each before moving on to the next — never a bad idea when you’re coming to something with fresh eyes. And considering that the first entry in Outdoors is a kind of “Cliffs Notes”-style truncation of the core concerns that animated Travel, budget-conscious comics consumers (I would assume that means nearly everyone at this particular point in time) may find this volume a pretty solid “more bang for your buck”-type of package. This story focuses on a drone transmitting images of the natural world back to its operator rather than passengers on a train as its predecessor did, but the “man (and his implements) vs. nature” dynamic is nevertheless present and accounted for (and obviously so, at that), and its fast-paced, even frenetic, pacing is a sudden and intriguing change of pace for Yokoyama, who’s best known for more lethargic, free-form story structures, and this focus on breakneck action is extremely well suited to the story’s narrow hyper-focus upon the mechanical object itself and its actions.

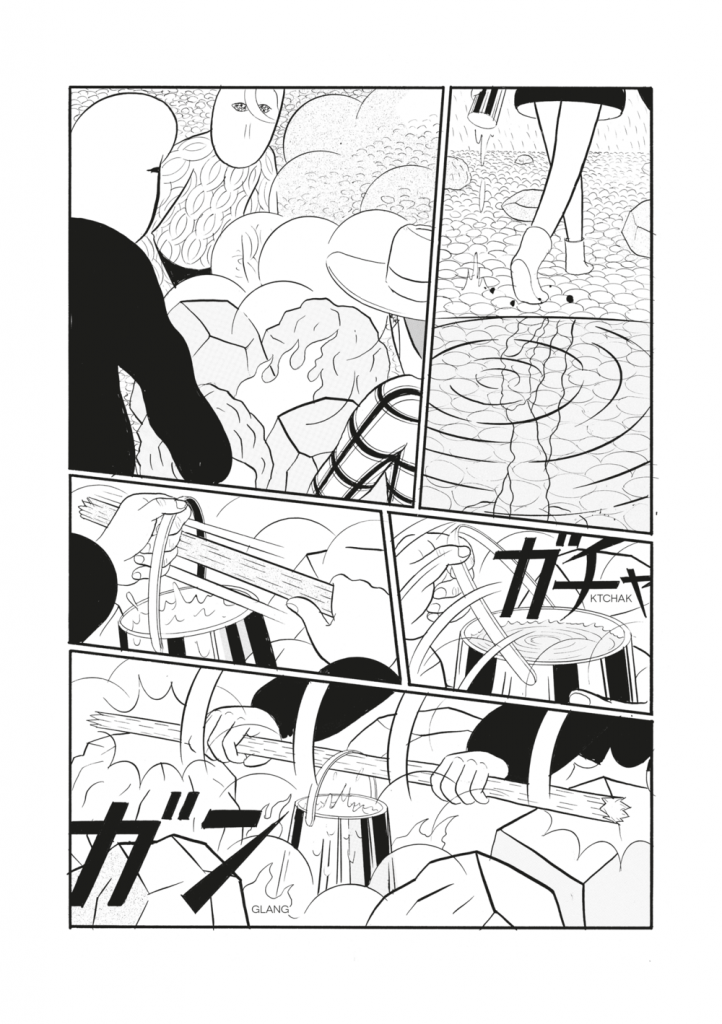

Ingeniously, Outdoors then presents a narrative much more in line with its author’s usual timing and pacing, a 60-page deluge of rain that starts as a shower and develops into a torrential downpour — one from which its four masked protagonists must individually take shelter, in equally-individual structures. You’re correct to assume that varying degrees of success are achieved, but that’s only part of the fascination here, the larger aspect of it being the hows, whys, and wherefores these varying levels are arrived at, as well as the visual observations of each of the principals involved. It’s staggering stuff, delineated in a manner that privileges the impact of what’s being seen over its nuts-and-bolts mechanics, and also offers plenty of room for interpretation when it comes to deciphering the reasons behind the artist’s bold choices for illustrating what should be, by rights, a fairly straight-forward type of story. If pressed, I might very well say that this second entry is my personal favorite of the bunch.

The third story in Outdoors represents both a thematic continuation and a rather abrupt career transition of sorts for Yokoyama himself, presaging the more hard-edged tone that Iceland would adopt. A trio of figures dressed in varying iterations of Old West garb set up camp in technologically marvelous ways, make a futuristic version of “Cowboy Coffee,” and “shoot first, ask questions later” in response to noise from the bushes, the end result of which is an antelope stampede upon their makeshift outdoor “lodgings” that leads to even more reckless gunfire — but none of the bullets hit their targets, because they may not even be there. This is terrific, action-centric, intense visual storytelling that demands much from readers and offers little by way of clear answers, but that’s a big part of Yokoyama’s appeal: he communicates universal concerns in a personal, even visceral, manner, but refuses to insult your intelligence and hold your hand through the process. The answers are there, never fear, but yours may not mirror those of another reader.

That being said, the act of translating these images from your eyeballs to your brain is one of the sublime pleasures of not just Outdoors, but of all Yokoyama works. His unusual, idiosyncratic, and bold “camera angles” are frequently both demanding and rewarding of the keen attention a reader pays to them. There’s no “easy” way to look at and read these comics, but their dynamism, their delicacy, and their sheer bravado consistently engage in a kind of dance with each other, all elements ultimately congealing and coalescing into a style of sequential storytelling that is utterly unique in the most precise sense of the word.

That uniqueness had led to Yokoyama accruing a large audience at home, and a fervent and loyal cult following around the rest of the globe. His work unmistakably bears, in all ways and at all times, the one true hallmark of auteurship, that being: it’s his and his alone and there’s no mistaking it for anyone else’s. The imprint he leaves upon the page — and, by extension, upon the readers of his pages — is unlike any other, and once it gets its hooks into a person, there are times when simply nothing else will do. These are comics that are mainlined directly into the visual cortex and then rationalized, providing a one-two punch as strong as — I kid you not — any art, anywhere in the world, in any medium. And while it’s hardly advisable for anyone who may be reading this to spend an excessive amount of time outside the house under present, coronavirus-dictated conditions, I’m going to buck all the experts that you should be listening to and instead recommend in the strongest possible terms that you get Outdoors immediately — and stay there for as long as you like.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply