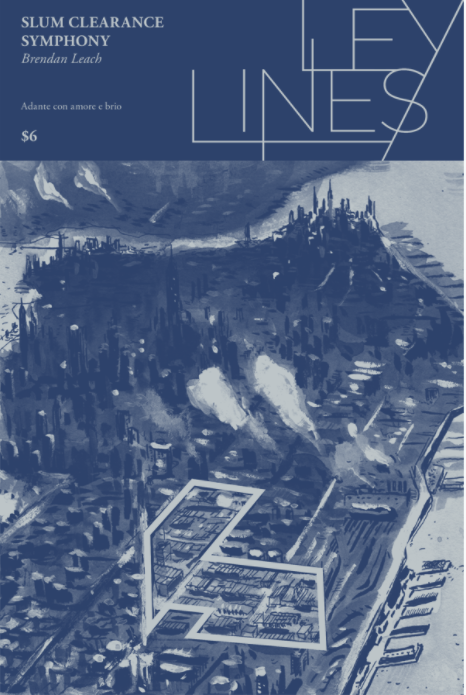

Keith Silva: Brendan Leach’s Slum Clearance Symphony, the latest in the Ley Lines series, co-produced by Grindstone and Czap Books, presents a thought experiment best embodied, perhaps, by the idiomatic inability to make an omelet without breaking a few eggs. The metaphorical omelet in this instance is Lincoln Center in New York City and the metaphorical eggs, the lives and culture of human beings.

Eggs and omelets aside, history hangs heavy in Slum Clearance Symphony. As Leach lays out, the Housing Act of 1949, designed to address the decline of urban housing, spurred uber city planner—and popular Zoom background fixture—Robert Moses, who knows a good deal when he sees (seize?) it, to remake New York City. With “sugar daddy” Uncle Sam helping fit the bill, Moses clears a tidy 16.3-acre parcel in Uptown Manhattan to build, arguably, an architectural showpiece for the greatest achievements of art and culture human beings have endeavored to create. This “great right” came at the “little wrong,” as Moses would have it, of razing the San Juan Hill neighborhood, home to thousands of low-income black and brown people.

Cultural erasure and displacement make for a hard sell, doubly so under the unctuous header, “urban renewal.” Leach has his villain in Moses and a cast of thousands of “have-nots” in the African American and Puerto Rican community who called San Juan Hill home. One of these inhabitants was Thelonious Monk whom Leach casts as a border-crosser between the “before” and “after.”

It’s not difficult to discern on whose side Leach leans. In a clever transition, he moves from a panel showing searchlights shooting up over a dwarfed Philharmonic Hall bulwarked by bulldozers, cranes, and temporary fencing to Moses’s back as he looms over a tabletop model of the completed project like a cartoon criminal mastermind.

Leach’s line looks light and quick, as if he were there on-site sketching what he’s chronicling in images instead of words. There’s a uniform unevenness to the straight lines and sharp angles of the architecture in his art that charms in its lack of detail, austere yet authentic, lived in. Leach constructs the story in much the same way, moments cobbled into a forever present like a collection of birthday cards on a mantle or vegetables ripening along a lintel. There is, yes, a symphonic quality to the story that begins quite cannily assembling the musicians, threads through the production of Wise and Robbins’s West Side Story (which was filmed during the construction), and ends with the dirty work of progress by asking (but not answering) who ends up on what side of the “meat axe” and why.

Well, Elkin, assemble the musicians and tell me how you like your omelet?

Daniel Elkin: I like omelets that honor their ingredients and are kinda spicey, Silva — just like Leach’s Slum Clearance Symphony.

In Leach’s telling of the opening night ceremonies of Lincoln Center, New York City Mayor at the time, Robert F. Wagner, sees Bob Moses’ edifice as an opportunity to “lend a strong hand in creating a better understanding between people all over the world for a better day of peace and understanding.” Leach then has then-Governor of New York Nelson Rockefeller opining that “the nations of the world will unite in showing their skill, invention, arts, and aspirations and doing so will educate the people to know their dependence on one another and create peace through understanding.” Even then-President Eisenhower is quoted as saying, “here will develop a mighty influence for peace and understanding throughout the world.”

The arts as a conduit for “peace” and “understanding” is the wadded aspiration you often hear bandied about by those who, typically, are funding these endeavors, those with the cultural cache and power base from which to define “art”, “culture”, and even “understanding.” Demarking what is “good” in these worlds, unfortunately, often gets tied up in what is “profitable.” And “understanding” for them, is really another word for “getting behind OUR way of thinking.”

“Peace” as the result of everybody toeing the party line.

Art as a disruptive force is only given its power when it can be commodified. It’s just a perpetuation of the system in the end. Can it change people’s lives? In the case of Slum Clearance Symphony, it can upend them entirely. Or, as Bob Moses said, “in order to get progress done people must be inconvenienced.”

Cultural institutions represent the values of the political will of those in power. That which is lauded as beneficial to all mankind has been filtered through a particular lens. If swaths of disenfranchised individuals must be “inconvenienced” in the process, it is always in the name of the advancement of “us all” — the “us” in this case, of course, being those who are doing the “inconveniencing”.

Brendan Leach is reminding us of this hypocrisy. Slum Clearance Symphony is reportage, not polemic. Leach’s choices of what to highlight in his storytelling is, assuredly, political in nature, but he is not wearing any sort of diatribe on his sleeve. Simply by expanding the focus, by allowing other voices into the narrative, he captures a fuller picture.

Is there cultural value to institutions and edifices like the Avery Fisher Hall, David H. Koch Theater, and David Geffen Hall? Of course, especially in the name of perpetuating a particular vision of value. These are temples, after all, whose eyes are a thousand blind windows.

And yet….

The arts do have an inherent importance, don’t they? There is a basic human need to create. There is only connection through expression. Acts of fabrication can bring beauty, pause, consideration, and, yes, “understanding”. They are fundamental to defining who we are and what we share, and, therefore, need venues for their dissemination. But the arts also need a fundamental openness and honesty at their core. There is an added value to each act of creation if we all understand what needed to be destroyed in order for it to exist.

And this is the added value of Slum Clearance Symphony.

Silva: My friend, let us speak plainly. I am more than happy to sit choir-side while my favorite firebrand for the dispossessed, you, rails from the rostrum. Of Leach’s argument, you write, “[he] is not wearing any sort of diatribe on his sleeve,” [only] “expanding the focus [for] other voices [and] a fuller picture.” Really? Leach is no impartial observer and Slum Clearance Symphony ain’t no study on the “objective.” It’s art. The style may be “reportage,” but “not polemic” (my emphasis), uh-uh, nope. Would you not have taken to your soapbox if what Leach delivers was not thick with opinion and a strong point-of-view? We agree Leach’s symphony trucks no sympathy for Moses. There’s no need for Moses supposes-es, everyone knows he was corrupt and politically speaking, as crooked as a dog’s hind leg. Damn, Elkin, there’s a whole book about it! To borrow a phrase, “other than that Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play?”

Leach stands for those who were written out of the narrative, at that time. Slum Clearance Symphony is proof a “fuller picture,” as you say, exists, should be seen, and not forgotten. A tear in the salted sea for sure, but in a rare time of reckoning (for some) in America, Leach’s voice is welcome and on time. What I’d like to know, Elkin, is how Slum Clearance Symphony works as what it is, a comic. You’re a pile of gasoline-soaked rags in the corner of the garage for this kind of stuff (or art, if you prefer). Leach barely has to strike the match. But is his bias not worth some interrogation as well?

Let’s begin at the beginning, with the violinist who is seen practicing and then performing the film score to West Side Story with her fellow musicians. Leach invests several pages in this unnamed woman’s story as he cuts and pastes together the destruction/construction of San Juan Hill/Lincoln Center. Her sections are shaded (and printed in blue) while the rest of the narrative is left unshaded with one (heavy-handed) exception, which I’ll address. Leach shows this woman working on her art in a space (Lincoln Center) that a cubicle and open-plan workspace dweller alike would kill for. She’s dealing with some physical pain which causes her to make mistakes, but she has “union insurance” and receives regular treatment. This woman is the epitome of a working musician and card-carrying artist, literally. So she has to take the subway to and from her job … and? Is the reader supposed to view this woman’s career as a symptom of what that ‘white devil’ Moses hath wrought i.e. she can make a living at her art? She ain’t no Thelonius Monk, but she’s putting bread on the table. You dig?

Further, Leach draws two panels of audience members during the philharmonic’s performance, each is a study in apathy. One is of a kid diddling on a cell phone and the other shows a woman waking her sleeping “honey,” whom we can assume is her partner and who has dozed off during “America.” [Insert your best joke here] Why does Leach include these different although similar audience reactions to this performance? What’s the point? Perhaps that is precisely what Leach is about throughout: what’s the point of (fill in the blank) if it’s ignored by “the people” it was made to entertain. Lincoln Center was built for both philistines and intellectuals, their money is the same color, you see, “for a small fee in America!” Don’t lay that at Moses’ feet.

Leach leaves the violinist off to ride the rails and evaporate into the cityscape. Her part played, she disappears — like many of the residents of the San Juan Hill — from the narrative. If Leach is trying to conflate an anonymous paid artist with medical insurance and housing (one supposes) with the displaced San Juan Hill residents, that’s a bit of stretch, dontcha think? And so, I ask, again, “what’s Leach’s point?”

The other moment Leach breaks out his shading tool is during a sequence showing the making of West Side Story. The actor George Chakiris, who played Bernardo in the film, was of Greek ancestry and not Puerto-Rican so like so many of his castmates his skin was darkened for the cameras. Leach shows make-up artists (more artists!) getting Chakiris “camera-ready.” Leach shades Charkiris’s face to show the transformation from Greek to Latin. Here’s where the “you-are-there” style of the comic works well, unremarked although clearly marked. But what is the reader to make of this? Is this example of brown-face supposed to comment on racial insensitivity in Broadway and Hollywood in the 1950s and 1960s respectively? Is the reader supposed to draw a connection between Chakiris’s brown face and Moses’s rampant erasure of a black and brown space? Where or with whom does Leach want to place blame, if at all?

My point, my friend, is for all Leach’s carefully constructed cat’s cradle of a narrative, he leaves more loose threads than, it seems, you’re willing to admit as you champion the powerless and call out the power brokers. You drape yourself in your finest sandwich board and clang away about peace, love, and understanding (not to mention art v. commerce) while papering over what this comic doesn’t show as it tells. We know. We know. Leach provides the ‘feels,’ but does he also advise to ‘do as I say, not as I do?’

Elkin: The problem with soapboxes, although they do provide one with the “higher ground” as it were, my friend, is that they are slippery bastards upon which to stand, especially when damp from the hot spittle of the person shouting forth from atop it.

Yet I stand with and upon my seemingly precarious position, and I will continue to sound my coarse cry. All perspectives are, in some manner, political. You see what you want to see in order to construct the narrative that best aligns with your understanding of how the world works. Where you put your eyes and focus is a product of your choices; how you convey what you have witnessed is filtrated through your comprehension.

You ask, “(w)here or with whom does Leach want to place blame, if at all?” I answer that blame is not the game here. Rather it is expanding the vision, opening the eyes, either seeing the fullness of the picture or reminding you of what you may have missed at your first glance.

This is why Slum Clearance Symphony is so successful as a comic. Comics are, of course, traditionally, the intersection of words and pictures, each with its own part to play in constructing narrative and tone. Leach’s “light and quick” line and “uniform unevenness” adds to the idea that not everything is as clear as we want it to be. In the very act of cartooning itself, Leach blurs the lines — he emphasizes the idea that not all narratives tell a complete story.

You talk about the violinist who “can make a living at her art,” yet you may not have the full picture of what this “living” is that she is “making”? So much of her journey seems concerned with this idea. There is the idea that her cushy violin gig at this cultural edifice is not enough to sustain the “living” she is “making”. She tells a younger musician, “But it’s getting harder to keep up my other gigs…” before being nearly run down by a Mercedes driven by a swanky-dressed couple who are about to dine alfresco. She boards the 7 train to Queens — presumably where she lives. Is this the good life? Are these struggles? Again, Leach makes no direct statements. There is no tirade or harangue. Rather, Leach makes choices as to what he wants his audience to see. He lets you choose the meaning of these panels. In a way, this is a classic example of the old adage about the text reading you. The understanding you make of what Leach has proffered tells us something about you, as much as it tells us something about me.

It’s the perspective upon the perspective. Don’t narrow your focus. Expand. Contain multitudes.

What cost is her “living”? Is it worth it? Is it fair? It depends upon what you understand those questions to mean.

I’m reminded of the words of the great American poet Lindsey Buckingham who once wrote, “Buy another fixture, Tell another lie, Paint another picture, See who’s surprised.”

Loose threads are only loose if you ignore the rest of the shirt, Keith Silva. Your final question about “doing as I say not as I do” might be more slippery than the soapbox upon which I have straddled here.

Still, all in all, I have no doubt that you would join me up here if I were to simply make the statement that Brendan Leach’s Slum Clearance Symphony is a great comic, a foundation from which an interesting conversation can spring, and solid work of art.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply