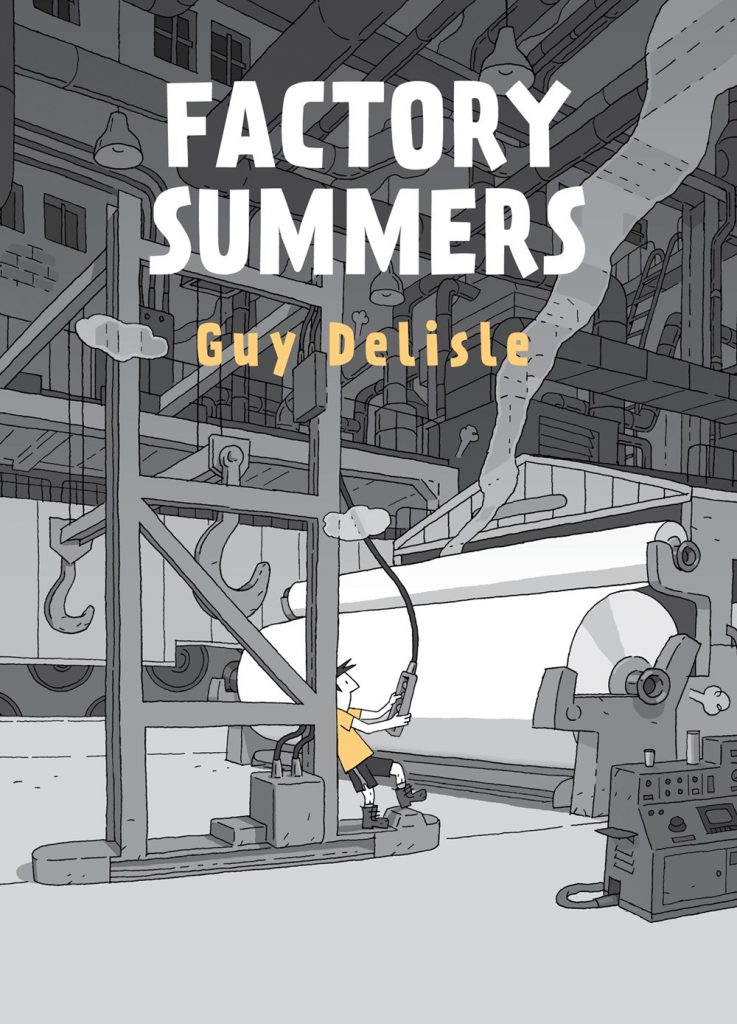

I’ve never worked in a factory, and I’m not sure that at this point in my life I ever will. But there’s something universal about Guy Delisle’s latest book, Factory Summers, published by Drawn and Quarterly in 2021. Originally published as Chroniques de Jeunesse (“Chronicles of Youth”), Factory Summers is about Delisle’s work in the Stadacona Mill in Quebec City on his summer breaks as an art student. The summer job is an institution of Western society; most young adults get one or at least try to. The summer job is a quintessentially transient thing, an interstitial moment between phases of life. But there is a lot of potential conflict and change in the ephemeral, and the summer job story is a perfect tool for Delilse to reminisce on his past and his relationship with his father.

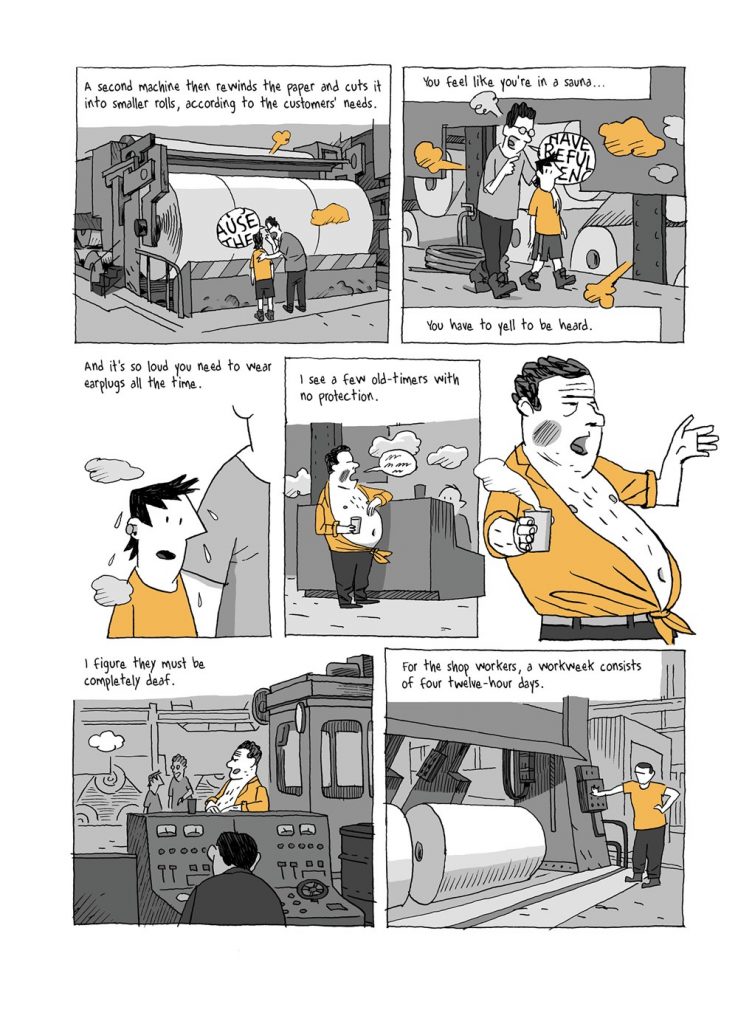

Factory Summers starts with Guy Delisle on the hunt for a summer job in between high school and college. His dad is an engineer at the local paper plant in Quebec City. It’s a pretty famous place — the place where newsprint is manufactured for big papers like The New York Times. Although he frets about his interview, Delisle has little trouble getting work, and it’s easy to see why: the work is exhausting and intense. Delisle’s job is essentially to babysit a giant roll of paper. If there is a failure in the roll, piles and piles of paper will ratchet out of the machine before it can be stopped; mess is inevitable, and that means cleaning it up. If the roll runs out, you put up a new roll. Little scraps of paper from the machine will need to be swept (or blown) away from the machine to prevent faults. Any faults or messes that the workers have to deal with are recycled, so to speak – all you need to do is to push that wet paper down a chute in the floor, and that pulpy mess will get reabsorbed into the process and start from scratch.

While I don’t recognize the factory floor and have never made it my business to work on one, I’m well acquainted with the danger that becomes Delisle’s constant companion in Factory Summers. Danger might as well be an illustrated character in the book for as much as it drives the narrative. The danger of a paper mill is fairly evident — masses of bulky paper, whirring turbines, screaming gears, and machines surround you at all times. It’s not so different in the rural heartland, where summer farmhands work next to spinning augers that can take your arm off in less than 2 seconds and unclogging grain bins where you can drown in wheat or soybeans. Delisle talks about industrial chemicals that made his throat sore for weeks. I’ve worked in hay mows where the temperature is well into the triple digits, all you breathe is dust and mold, and one wrong step means a 40-foot drop to bare earth or dirty concrete.

When you spend enough time in environments like that, danger becomes your brother. The jocular banter of blue-collar men takes on a morbid tone. While Guy Delisle mostly thinks about these moments in inner monologues, tales of death and dismemberment are the stuff of regular conversation between the men on the floor. On the factory floor, you’re face to face with your mortality all day, and that force will either make you see stars, make you swagger, or it will break you.

Delisle spends his time around a lot of swaggering and/or broken men, and, in moments of rest during shifts, he sits with other floor workers in a small air-conditioned shack. He’s the young guy, the easy target, the outsider, so it’s easy to catch shit in places like this. This is especially true since Delisle is an artist whose passion is not easily explained. But if you do enough work, the guys on the line will eventually come to include you, especially when the hard hat-wearing bosses come down from their offices on high. At that point, it’s a unified front, bullying and teasing be damned. This hierarchy of opposition in interpersonal relationships, and the way these relationships glide past each other is one of the major recurring themes of Factory Summers. The way that men communicate with each other, the grandstanding and posturing, the harassment, the dreaming, the dick-measuring, even the gruff gentleness, all are examined under Delisle’s microscope. Each moment in the shack, where Delisle has to explain that yes, he wants to be an animator, he is going to be an artist, feels familiar and tenuous.

Wrapped in this essential theme of masculine communication is Delisle’s relationship with his father, a distant man by habit if not by choice. Their relationship is strained by underuse; even though they work in the same building, Delisle’s father moves in and out of his life like a ghost – a glimmer noticed in passing, but as soon as you turn, it’s gone. Delisle comes at these personal reminiscences with something akin to bemused confusion. Delisle finds it hard to disentangle the Western ideal of masculinity and its effects on relationships between workers, fathers, and sons.

In the midst of all of this, Delisle is also telling his story of growing into adulthood. We see him struggle to make decisions, try to meet girls, and find a future that he’s going to love. In that sense he mostly succeeds; at the end of the book, he’s offered an animation gig and, in a snap decision, leaves the factory floor, never to return. In most of the English-speaking world, we know Delisle for his success as an author of travelogues, reportage, and parenting advice. Factory Summers feels like a much more foundational work. For me, it gets at the essence of the author more than any of his previous work. It’s a story of growing up and finding the world, being dissatisfied with that world, and coming to terms with that dissatisfaction.

In Factory Summers, the abrupt transfer of Guy Delisle to his new career as an animator leaves the narrative somewhat stilted, and if the book had ended at that point, I doubt I would know what to say about the work. But an epilogue clears the way and draws the entire narrative back onto itself. As Delisle and his brother clean up his father’s apartment after he dies, he finds stacks of his books, as well as encyclopedias and other detritus of a life lived in solitude. In a flash he finds himself standing over papers, bits, and bobs, and is again tasked with cleaning up, maintaining order, and taking care of things until they end. His grief, his memory, all of the things of his father’s life lie around him as he has to make a decision, and, like all those summers of his youth, he makes the same one. If it can’t serve you, if it can’t do what it is meant to do? Push it down the chute, and start the roll spinning again.

Leave a Reply