There’s a particular thing that Rodger Binyone does that is unique unto him. I call it “neon punk” not only because the descriptor works, on levels both aesthetic and intellectual, but also, admittedly, because I simply can’t think of anything better — which is either proof that I’m not all that particularly original, or that I’ve hit the nail right on the head, take your pick. Whatever the case may be, though, the simple fact is that Binyone’s comics are true auteur works: there’s no mistaking them for coming from the mind and hand of anyone else.

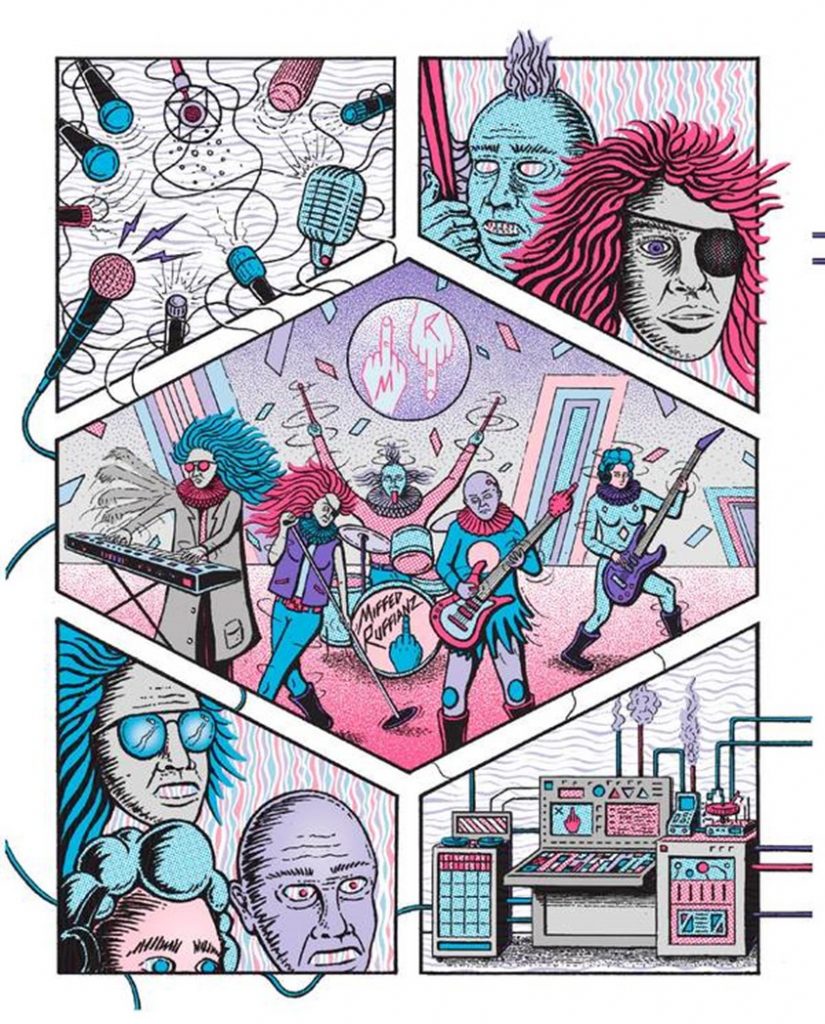

Which isn’t to say that they don’t necessarily fit rather comfortably somewhere along and within the makeshift gradations of a larger stylistic continuum — certainly Pat Aulisio and William Cardini come to mind to a certain extent, as do the more straightforward id-channelings of late-period Jack Kirby — but Binyone is unquestionably marching to the beat of his own drummer, even as he traverses a somewhat worn road of “cosmic trippiness.” Silver Sprocket, publisher of his latest, Miffed Ruffianz, refer to the artist as a “master of psychedelic mechanics,” and that strikes me as a notable example of truth in advertising in that Binyone marries mechanical precision with the free-form and free-wheeling ethos of psychedelia literally like no one else, but the mental “sound” conjured by this new work is hardly that of Yes or The Doors and is instead something halfway between Black Flag and Kraftwerk, if you can (or even care to?) imagine such a thing. And I can assure you that musical analogies come freely here because the Miffed Ruffianz of the comic’s title is a band — or, perhaps more accurately, a multi-species, revolutionary, techno-anarcho sonic battalion at war with their sworn enemy (as well as yours and mine), conformity.

That conformity has a specific face and name here — Regularz — but it could just as well be all squares of all stripes, and it’s not like Binyone is out to disguise this fact. Indeed, what this book (as well as, in fairness, most all his other comics) is about moreso than narrative, and, perhaps, even moreso than art, is attitude, and if your’s isn’t adequately rebellious, you’ve come to the wrong place. Certainly there’s irony aplenty in the fact that Binyone expresses this inherent punk sensibility in such a controlled and calculated manner, but that’s both part of the charm and a subversion of the staid and lifeless right where it lives and feels safest. I mean, if you can engineer a revolution, then of what use are engineers themselves? And let’s be honest — a well-timed and well-placed “fuck you” hits a lot harder than a random, haphazard one that could be directed at just about anyone, and for just about any reason.

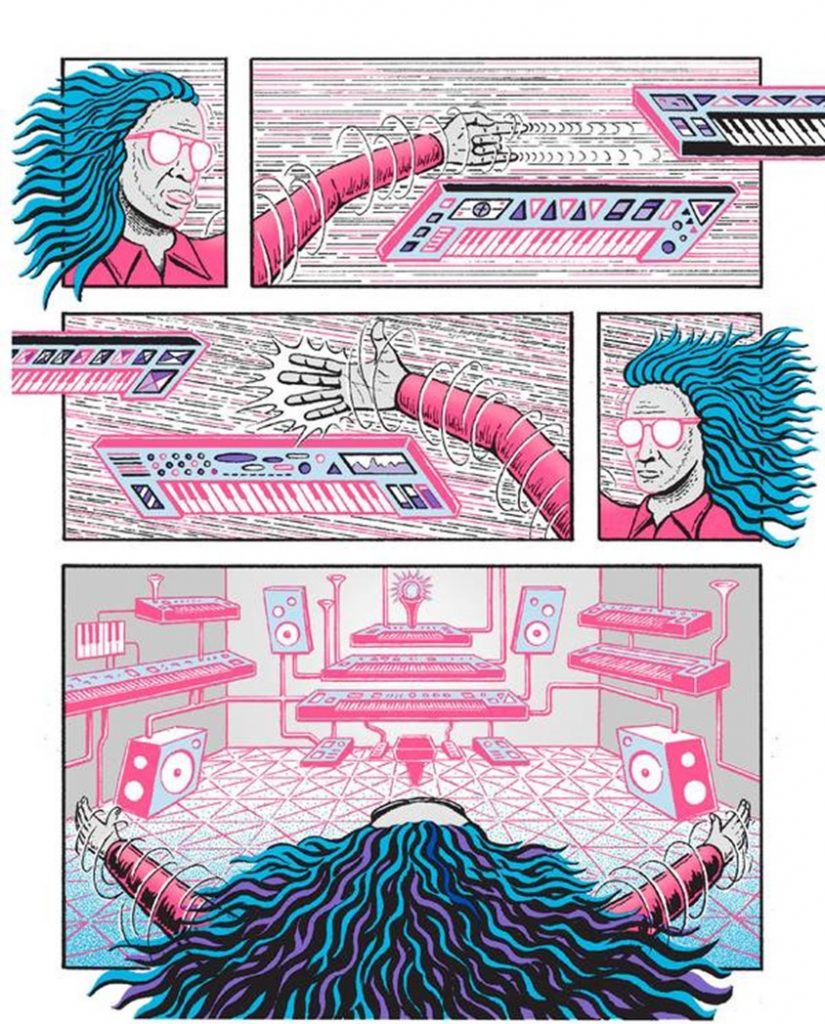

Still, I do keep coming back to that idea of engineering, of precision, and not without reason. In a Rodger Binyone comic, the production techniques utilized are utterly inseparable from the work itself, a crucial linchpin of the entire aesthetic experience he’s creating. Having gone the silkscreen and risograph route in the past, with Miffed Ruffianz he expands his horizons to Pantone printing, and to say his neon-infused pastels pop right off the page is like saying The Ramones played “kinda” loud. This is flat-out arresting art that comes at your optic nerve in the form of a full-frontal charge, brooking no opposition and taking no prisoners. It’s a welcome invader of your visual cortex, sure, but that doesn’t mean its intent is what you. I, or any other rational human being would describe as peaceful — but then, if you wanted relaxed and mellow, you’d be listening to Perry Como.

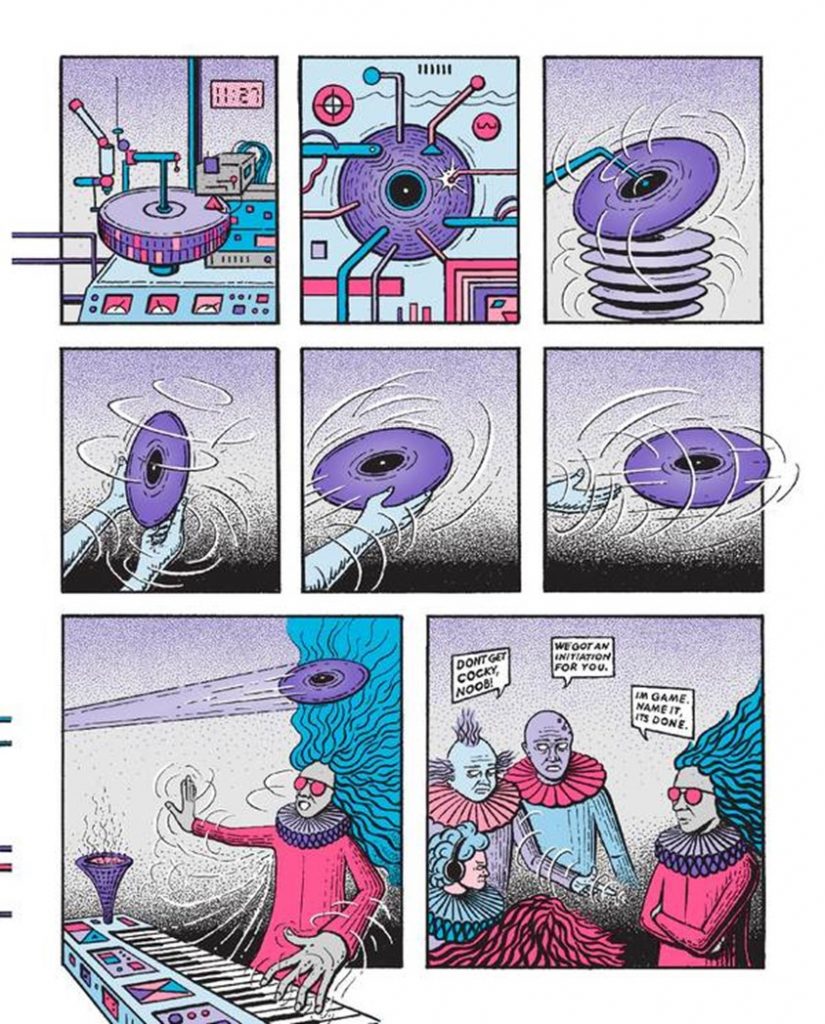

If there’s one criticism you could level at this lavishly-produced, oversized publication, it’s that in pure narrative terms it’s rather threadbare. Still, I would contend that “pure narrative terms” are the last thing on its metaphorical mind, and that bogging down the proceedings with too much plot, too much dialogue, and frankly even too much logic would ultimately stand in the way of Binyone getting his message across — and while that message is admittedly as simple as they come, it’s also vital, perhaps now moreso than ever. At its most basic, it boils down to “herd mentality sucks,” and at its most philosophically grandiose it’s “freedom is what it’s all about, baby,” and there’s really not much gulf between the two, nor should there be. After all, life is at its best, its most memorable, its most alive when every moment is charged with urgency, when every breath and heartbeat are pregnant with possibility. Enemies come in many shapes and sizes, sure, but, at the end of the day, they all have one thing in common: their goal is to stand between you and whatever the hell it is you feel like doing. If you’ve ever felt like moving your enemy out of the way by force is exactly what they deserve, trust and believe that Binyone not only gets that, he translates that urge into an exuberant visual language that brooks no compromise because it exhibits none.

Where that leaves us is anyone’s guess, but that’s also rather the point. Life is what you make of it, so make of it what you will. And while such a sentiment would seem to be diametrically opposed to discipline and responsibility on a conceptual level, the amount of each that has gone into the creation of Miffed Ruffianz proves that even when you’re hard at work, you can still have a good time, so hey — laissez les bontemps rouler, and never let ‘em stop. Anything can be a party if you really want it to be. Now excuse me while I check out of this review, open a bottle, and crank up the turntable. And if my neighbors decide to complain about the noise, rather than scream back at them through the open window, maybe I’ll just try inviting them over instead.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply