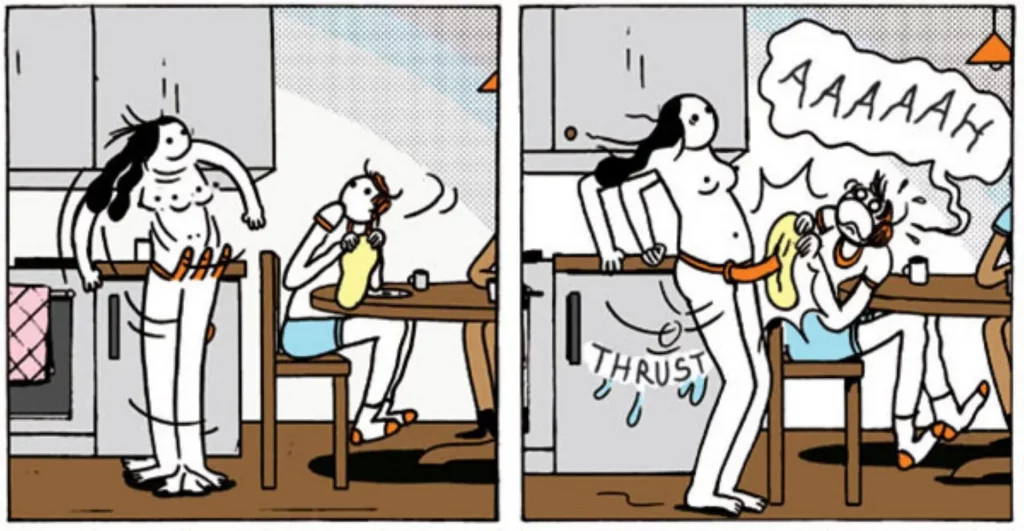

In the first few pages of Tara Booth’s Nocturne as well as in an early vignette in Elizabeth Pich’s Fungirl, there’s a sequence where the nameless female protagonists appear wearing a strap-on dildo. In neither case is this meant to be shocking, transgressive, empowering, or even erotic. For Booth, it’s the start of one long gag with the precise mechanics of a Boob McNutt strip from Rube Goldberg. For Pich, her Fungirl character simply walks into the kitchen wearing a strap-on and nothing else because this is typical behavior for her. The scene ends with several pancakes being pinned on her protuberance.

For both artists, this type of scene is entirely business as usual in their comics. It’s not that their characters don’t suffer from the kind of body image problems imposed by a patriarchal society with impossible beauty standards. In fact, it’s a frequent topic of discussion, or in the case of Booth (whose comics are silent), illustration. For Booth’s stand-in and Pich’s Fungirl, it’s clear that both characters just stopped giving a fuck a long time ago. There’s a sense that long before the reader is introduced to these characters, they are self-aware enough to realize that there is no way for them to fit into conventional society, so they may as well pursue every freaky desire, every pleasure large and small, every whim and urge for adventure that they can conceive on a moment-to-moment basis. Their concerns are far more immediate and modest than worrying about careers, conformity, or anything other than what might bring them pleasure and/or relief next. This surrender brings a kind of enlightenment: the understanding that the experience of being embodied is absurd, ridiculous, and completely stripped of dignity.

The result for both books is that they both have lead characters with horrible boundaries but a great deal of goodwill. They are chaos agents who blow in winds both good and ill. They are fun until they go too far. They are manipulative but also stir complacent characters out of their own personal miasmas. They are walking cringe generators, but one can’t help but laugh.

Pich and Booth explore similar ideas in different ways. Booth’s comics are not only silent but her deliberately crude and expressive line is paired with a painted approach. Her comics have more in common with Egon Schiele’s paintings than a typical comic, and she fully exploits her grotesque, exaggerated, blobby character design for laughs. Every movement and gesture is so exaggerated and cartoonish that one can’t but laugh at the contrast between what is initially illustrated (the sex scene) and then laugh again at the structure of her humor. For both Booth and Pich, it’s not unlike reading Peter Bagge’s series HATE; Bagge’s rubbery character design and exaggerated expression made the frequent sex scenes ridiculous, not arousing.

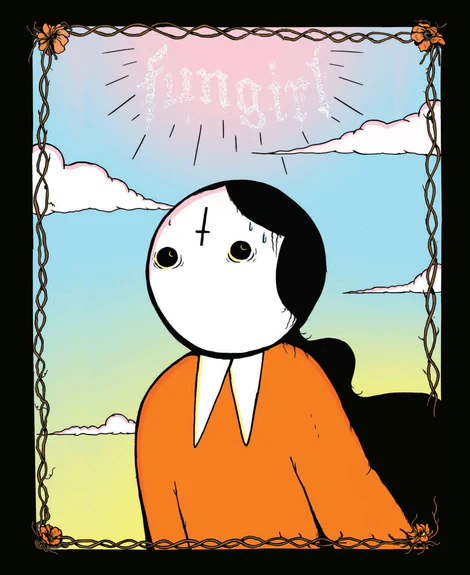

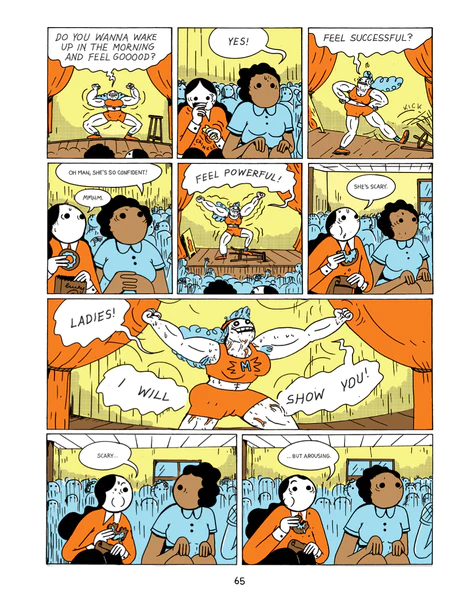

Pich’s Fungirl is closer in spirit and execution to Bagge’s work than Booth’s. Even Pich’s flat color palette is reminiscent of Bagge’s later issues of HATE. A lot of the gags are verbal, but it’s the eccentric character design that unlocks everything else. Fungirl’s round head, black dot eyes, lack of a mouth, and red shirt with a white collar make her a superb vehicle for all kinds of nonsense; her appearance as an iconic and slightly abstracted figure makes it easier to quickly project any emotion. She is the walking definition of irrational confidence, as she is competent in nothing, bullshits her way through life, takes advantage of others whenever possible, and gets away with it in part because she’s great at cunnilingus. Every now and then, she gets a wake-up call that she lacks ambition and direction, but she usually manages to ignore those moments of clarity.

Both Nocturne and Fungirl may seem like freewheeling chaos at first, but both Booth and Pich have rock-solid structures supporting all of this nonsense. In Nocturne, the young woman is fucking her boyfriend with a strap-on (him wearing socks and a t-shirt is such a hilariously perfect detail) and then stops, asking him to turn around for a surprise. She opens a box with a cat-o’-nine-tails, and with a beatific smile, slashes his ass with the whip. Hoping for a dildo of some kind, he’s furious and throws her out. The slow, panel-by-panel process of her putting on her clothes (still wearing the strap-on, mind you), putting the whip back into the brightly-colored gift box, and sadly backing away is an awkward, cringe-worthy triumph.

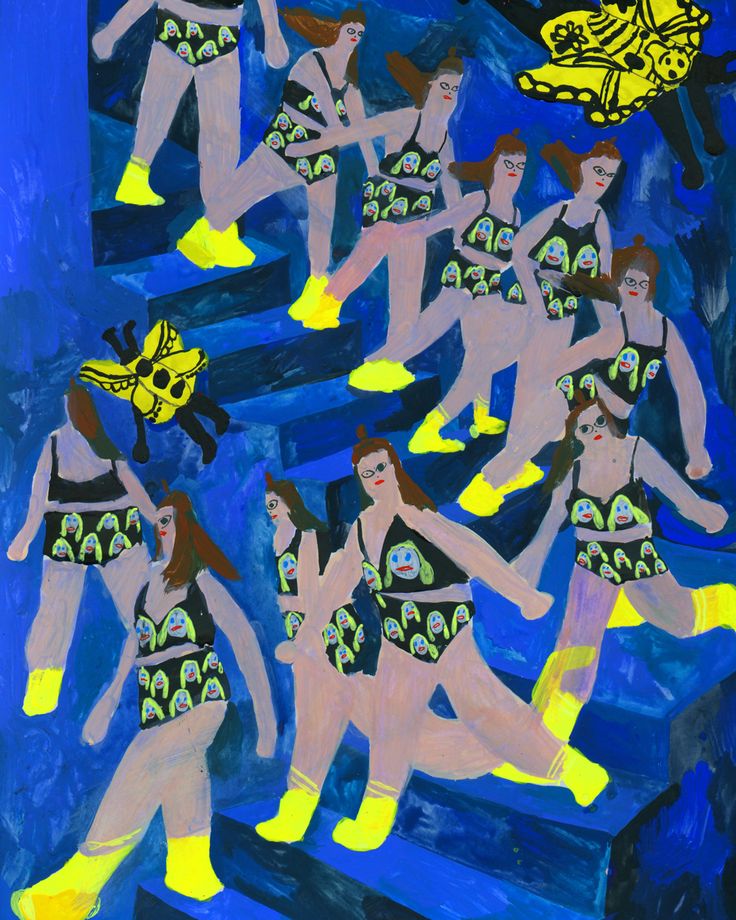

The second act finds her tossing and turning as she tries to go to sleep. Sleep eludes her, angering her into trying to exercise her way into exhaustion. It fails, but she finds a bottle of sleeping pills in her medicine cabinet, and she promptly swallows the whole bottle. She tries to exhaust herself again as her pupils become extremely dilated and a magical butterfly gently brings her downstairs using a De Luca effect that also brings Marcel Duchamp’s famous Nude Descending A Staircase to mind. Walking past her roommate, she goes to the fridge, takes out her roommate’s cake labeled “Don’t touch my fucking cake!” and proceeds to stick her face in it. After all, the butterfly told her to do it.

Gorged on red velvet cake, and its remains smeared on her face, she is finally able to sleep. Her furious roommate barges into her room; it’s evident that they’ve had conflicts before by the dismissive expression on the first woman’s face. However, when she touches her face and finds cake, Booth pulls off one of the most hilarious storytelling solutions I’ve ever seen. The protagnist reaches for the cat-o’-nine-tails, still in its gift box, and hands it to her roommate. The roommate is absolutely delighted by the thoughtful gift, ties the very willing woman to the wall, and rears back with the whip as everyone lives happily ever after. As always, if you see Chekhov’s cat-o’-nine-tails in Act 1, you’d better see it used in Act III. Booth is absolutely committed to the importance and immediacy of each moment and makes the reader follow along, creating a weird sense of pacing that enhances this final, unexpected punchline.

While Nocturne is short (66 pages), Fungirl is more expansive at over 250 pages. There aren’t any clear chapter breaks, except for the use of absurd interstitial illustrations, such as Fungirl and Peter imagined as Wayne and Garth from Wayne’s World. While there are a number of twists, turns, and blind alleys in the narrative, there is actually a fairly coherent, character-driven plot in Fungirl. Fungirl is an aimless hedonist who knows she doesn’t fit in but flouts societal conventions as a way of finding her own space. However, her lack of purpose secretly eats away at her. Her flatmate is sensible Becky, an overworked nurse who dreams of becoming a doctor. She and Fungirl were once involved. Becky’s boyfriend is Peter, an overly sensitive kindergarten teacher who spends most of his time at their apartment. He’s worried that Becky doesn’t take him seriously.

As a chaos agent, Fungirl disrupts healthy boundaries and habits, but she also shakes up inertia and complacency. She pushes Becky to apply to medical school and recognizes her brilliance. She shakes up Peter on a regular basis and encourages him to be more direct. Fungirl rescues Peter from a gang of frat bros by throwing her period blood on them. She concocts an elaborate revenge scheme against a rock star mortician (he lectures that “there’s one thing we all wish for in death…to be sexy!”) who slighted her boss. Staged necrophilia was involved. There are some similarities to Simon Hanselmann’s work as well, with Peter being a bit like Owl and Fungirl acting a lot like Werewolf Jones, minus the wanton cruelty.

As the absurd vignettes and adventures pile up, their consequences have meaning. Fungirl is fired from her job by accidentally burning down the “jar room” of oddities at the mortuary. Peter kisses Fungirl and tells Becky it was Fungirl’s fault. Becky goes to med school and things get worked out with Peter. Fungirl hits rock bottom with her fuck-ups. In addition to pissing off her friends and getting fired, she’s defenestrated by a lover and lands on an innocent woman on the sidewalk. In fact, she crushes the woman’s eye with her vulva. Fungirl talks to the victim in the hospital, not letting on that she fell on her, and the victim bemoans that there isn’t a vulva emoji. Then, the victim dies.

This leads to the grandest and silliest adventure yet, but one that’s also somehow emotionally resonant and Fungirl’s redemption arc. She travels to the far-off island where emojis are approved, has a hallucinogenic vision quest, and eventually comes to the Ministry of Emojis. She fills out an application, takes a photo of her own vulva as reference, and heroically finishes her totally nonsensical, meaningless quest. When the emoji is ready, she sends it to her friends. Of course, the only thing she’s done is make a gesture outside of her own pleasure and does something out of duty and not just guilt, but a desire to make amends. The book ends with her saying, “Now what?”, because this is just the very beginning of trying to find an ambition, but it finishes her particular character arc for Fungirl.

The acceptance of the absurdity of being embodied is what allows both Fungirl and Booth’s character to pursue pleasure. They have a total lack of shame with regard to their desires, and it’s clear that they take great pride in providing pleasure for others, as well (it’s one of Fungirl’s more selfless qualities, in fact). That pride in their pleasure is a pretty radical act, but what’s even more radical for Booth and Pich is that all of that is secondary to emphasizing the sheer ridiculousness of sex while treating desire (especially that of women) and sexuality as givens. What’s shocking about Fungirl and Booth’s character isn’t their sexuality, it’s their utter lack of boundaries that then leads to a series of hilarious escapades.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply