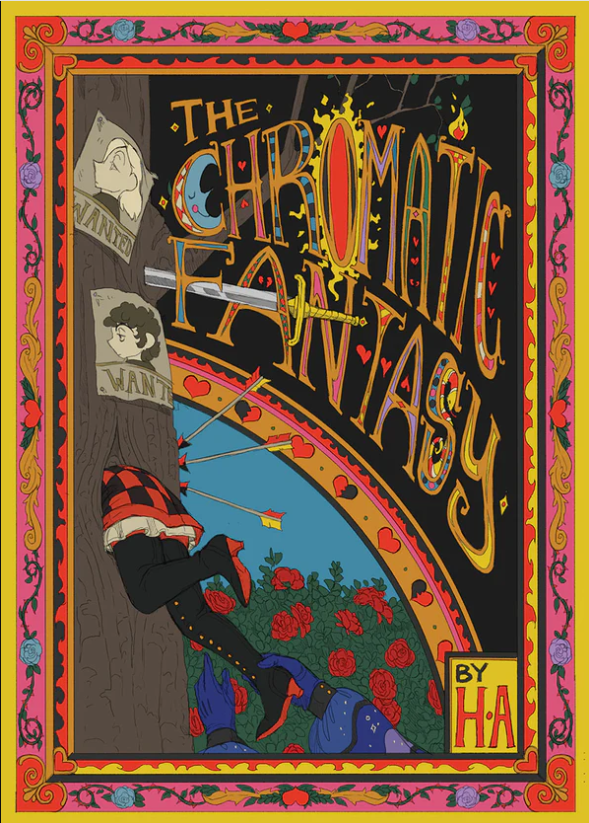

About halfway through reading H.A.’s 2023 graphic novel The Chromatic Fantasy, I found myself thinking about the tweet that goes “If you gave a medieval peasant a Dorito they would die instantly.” Anachronisms are funny; it’s understandable that the image of flavor-blasting a 13th-century guy dominated Twitter for a few weeks. I was thinking about this old tweet because despite being set in medieval Europe(ish), one of The Chromatic Fantasy’s two main characters had just described their daily routine thusly: wake up, cigarette, 24 oz vanilla latte from Starbucks, experience IBS. “Ok,” says the other. “I think there are some lifestyle choices that could help you with the IBS.”

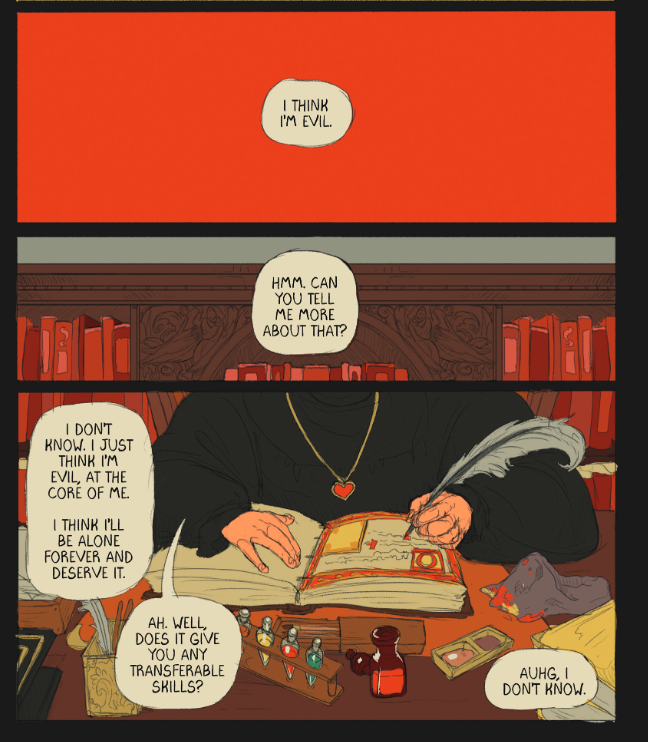

The experience of reading The Chromatic Fantasy is one of tonal and technological whiplash. It follows Jules, an ex-nun who makes a deal with the Devil and gets exiled to party, gamble, and flirt to his heart’s content while being impervious to all harm. Jules meets Casper (the IBS-haver) as they’re trying to steal from one another. They develop a relationship first as co-criminals and then as more serious lovers. The comic has a medieval aesthetic, but it’s set in a fantasy realm that is technologically porous. The main character sometimes has a smartphone. There’s trans healthcare at Starbucks. A sword lies on the bedside table next to a Monster Energy.

Both Jules and Casper are trans men, and both have problems with authority figures whose demands begin with what looks like love, only to turn into authoritarianism. For Jules, this is first his abbess and then the Devil; for Caspar, his former employer the Queen. Their relationship, in contrast, is open and creative, providing what’s implied to be a bandage for past wounds. So while the story starts as “be gay, do crimes”, Jules and Casper become examples of how people can flourish when they’re not being controlled.

As much as it’s mostly aesthetic, the medieval visual inspirations for this comic are clear. My favorite visual aspect is the clothing, which H.A. draws in layers and heavily involves cloaks, flowy dresses, and headgear. The chapter dividers are lettered like an illuminated initial in a medieval manuscript, with the characters around them like marginal illustrations. The comic lives up to its name throughout with neon flourishes and multicolor lettering, which reminded me of the flowers and leaves you can find in French marginalia, in particular.

From a medievalist’s perspective (hi!), it’s tempting to see this comic as its own attempt to place transness in the Middle Ages. In the introduction to Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt note that despite the differences between medieval and modern conceptions of gender, gender transgressions from the past nevertheless allow the construction of a trans history: “these texts showcase what medieval people were told to believe, the ways that gender was being considered and discussed, and the questions that were being asked that these texts tried to answer: trans lives could be envisioned and, therefore, trans lives could be lived.” M.W. Bychowski argues that it’s wrong to conceive of transness as a narrow 20th and 21st century phenomenon. Rather, it’s a “part of the biodiversity of the human species” aided in the Middle Ages in the same way as now by things like clothing choices and name changes.

So, yes, there were trans men in the medieval period, and maybe they were even going to Ye Old Starbucks. But H.A.’s comic is not trying to make an argument about presence or absence in actual history. In an interview, they seem hostile to that idea, saying, “I also just think the pursuit of ‘historical accuracy’… is just a gargantuan task anyway, especially for a kind of dumb comic, so I may as well just be wrong in ways that are obvious and funny.” H.B. adds more explicitly: “In many ways, the story isn’t really about the middle ages, anyway. It’s about gay people right now.”

Jules’s struggle against the Devil and what it represents – the suggestion that he hasn’t really escaped his life as a nun and that he might be doomed to be a woman – follows him through all his adventures with Casper. Even when he joins a queer theater group and goes on bigger heists, he deals with the usual “what am I doing with my life?” which anyone in their 20s might be familiar with, but also the lingering feeling that his new happiness is temporary. His inability to die is a plus, but increasingly it becomes another source of apathy: if he can’t die, then why care about surviving? While I felt the comic’s ultimate resolution of Jules’s struggle was rushed given how central it is to the story, it further represents that the only obstacle to Jules and Casper “living happily ever after” is the judgment of others about what role they’re supposed to fill.

H.A.’s comic is not concerned with representation in a broad sense. But although it doesn’t share a project with trans medieval studies, it does share a result: trans lives being envisioned and, therefore, “lived”. The comic also feels like a response, on some level, to the neverending demand that trans history prove itself to a hostile audience. If a trans person’s existence in the medieval period is seen as just as impossible as a smartphone, then why not write a story where there are both? Being playful with the use of medieval aesthetics stretches the place those aesthetics can hold in our imagination, and that’s a good thing. So embrace the anachronism: like the spice on a cool ranch Dorito, it only makes the overall package tastier.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply