Zine culture has been entwined with autobiography since the desktop publishing revolution of the 90s. Being able to easily print your own work and get it reproduced cheaply inspired a generation of writers and artists and the form remains a rich vein to this day. The intimacy of the minicomics object lends itself to autobio, like a diary or personal sketchbook. It’s appealing to those who want to share and explore who they are and what life means, and it’s become especially attractive to those whose voices have traditionally been silenced by the mainstream: women, people of color, and LGBTQIA people. Just as the early days of minicomics and zines created a mail network of like-minded artists, so too has the modern mini boom created networks for marginalized creators. Autobiographical minis stand apart from the more recent wave of graphic memoirs because the stakes are lower; a mini doesn’t have to tell your entire life story or even provide a sustained narrative. Just looking at a random sampling of minis I’ve acquired within the last year reveals how autobio can be a lifelong pursuit, a statement of identity, a way to explore mental health, or simply a way to engage the world.

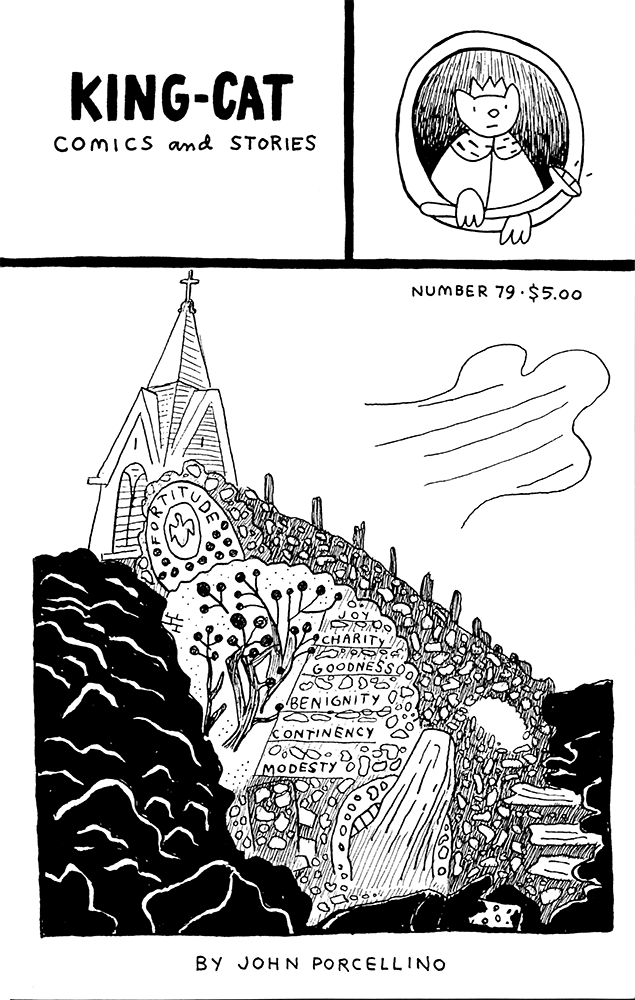

John Porcellino is a foundational figure in minicomics history, both as an artist and distributor. His Spit And A Half distro has long been an integral piece of creating and sustaining an interest in and market for minicomics, as his taste is impeccably sharp and also wide enough to encompass the newest and most exciting artists arriving on this small scene. Of course, Porcellino’s own career-long pursuit has been his series, King-Cat Comics And Stories. While it’s been collected in various formats over the years, those collections are supplemental. The simple and subtle pleasures of each individual issue are the core of the King-Cat experience.

Porcellino’s clear, simple, and stripped-down line is the key to his versatility as an artist. Whether he’s drawing a scene from nature, writing comics-as-poetry, talking about Zen, relating a personal anecdote, or just drawing a gag, the spareness of his line gets at the essence of his subjects. It’s an excellent example for young cartoonists to understand the difference between cartooning and illustration. Porcellino is a master of subtle gestures, body language, and quietly expressing emotions through his figures. His use of negative space is masterful. His panel-to-panel transitions are fluid. His panel layouts are clear, and his drawing only enhances what he’s trying to express — it never detracts.

The most recent issue of King-Cat (#79) marked his 30th anniversary, and it sees him in fine form. There’s an upbeat quality to this issue and an outpouring of actual stories missing from some recent issues, which relied more heavily on letters and observations about nature. Porcellino has always written elliptically about his physical and mental health struggles within the pages of King-Cat, leaving these details to his original graphic novel The Hospital Suite. Still, passages in his minicomics about pain and loneliness always made it clear when he was particularly struggling with these issues.

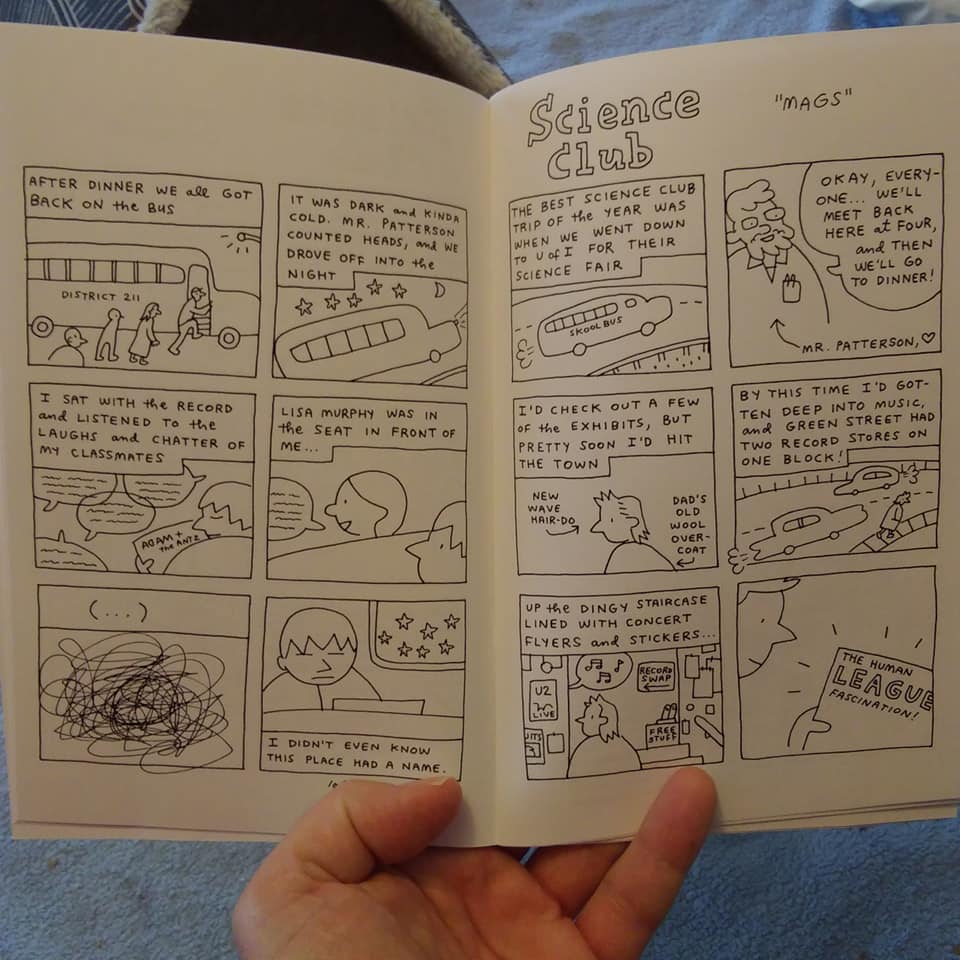

This issue of King-Cat is light on such details. Instead, the bulk of the issue is a series of funny reminiscences about his days in his high school Science Club. Porcellino doesn’t talk much about the club itself but instead is far more interested in the “kickass field trips” they went on. In particular, the focus is on liminal moments: bus rides between destinations, restaurants they went to, and brief stops in towns where Porcellino could find records. In one such store, he discovered a zine called Auhtistic Chainsaw Gazette, “And all the creative wires in my head started to spark and short-circuit. I stepped across a threshold from which I have never returned.” Later, he meets the person who made the zine, which only confirmed that he had fallen in with the right group of people. It took 79 issues and thirty years, but Porcellino finally revealed his origin story. It was a typically understated way for him to celebrate something, swerving the reader one way and then ending on an unexpected note.

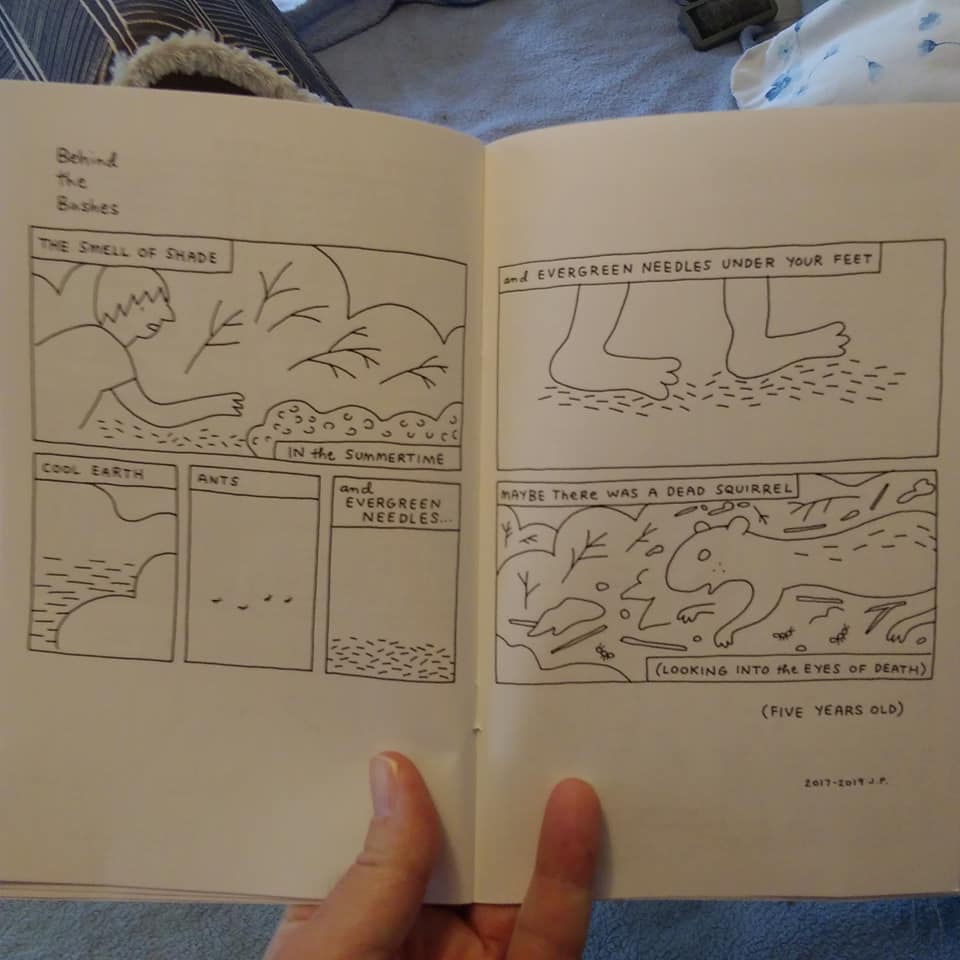

Even the comics-as-poetry in this issue of King-Cat is filled with this sense of joy. “Night Poem” uses a standard Porcellino poetic technique, paced so as to be read slowly as though one was to take a deep breath with each panel. The final panel, revealing his beloved dog Gibby popping up in an otherwise quiet night scene, is deliberately playful, as though Porcellino wants the reader to know that not every poetic observation has to be melancholy or profound.

That brightness continues throughout the rest of the issue. In various short pieces, Porcellino recounts an anecdote about the kindness of his grandfather, recalls the feel of pine needles under his feet as a child, and shows his wife Steph the mysterious Gravity Hill. There are plenty of the usual features a reader expects in King-Cat, like the traditional Top 40 list of things he likes, nature drawings, more gags about dogs, a letters column with cat drawings from correspondents, etc. He also reprints a Gabrielle Bell comic where Porcellino features prominently as a character, which doubles both as a gift for him and a gift for those readers who hadn’t seen it already. Throughout King-Cat #79, there’s a looseness to Porcellino’s line that speaks to the energy present in his pieces. He’s an artist still at the height of his powers. It’s no wonder that he’s been an inspiration to so many with his willingness to be vulnerable and real.

Certainly one descendent of Porcellino is Kevin Budnik, who regularly releases new issues of his diary comic It’s Okay To Be Sad. In terms of form, however, his comics have that familiar daily four-panel layout that James Kochalka used for years with his American Elf daily diary strip. There’s a beautiful simplicity in having the task of boiling down one’s day into four panels and creating something resembling a single thought or loose narrative. I’ve always found Kochalka’s work to be cloying and precious in a deliberately performative manner. Even when he was talking about important or emotional matters, there was a layer of artifice that kept the reader at bay.

That was also true of Budnik’s early work, like in his first collection, Our Ever-Improving Living Room. These strips are funny and get across a feeling of what it’s like to be an art student, but they don’t really spill any ink, so to speak. When Budnik started doing strips about his anxiety and eating disorder, one could feel the veil lift. Drawing those comics was clearly therapeutic for him, even if drawing them was sometimes difficult. Here, all of Budnik’s virtues as an artist are present: his pleasingly ratty line, his strong sense of pacing, his firm narrative voice, his knack for capturing the beauty of small moments, and his ability to break down days to their essence. He has turned his skills to being savagely honest about everything — especially himself.

In the January 2019 issue of It’s Okay To Be Sad, Budnik adds color to the equation, giving his strips an extra sense of richness. His use of color is sophisticated and subtle, as he accentuates his drawings but doesn’t overwhelm them. The very first strip in this book breaks down a session with his therapist as they discuss grief, guilt, and how to respect boundaries. Some later strips are dedicated to poetic moments in the Porcellino style, while others are part of an ongoing chronological account of his life. In this issue, he moves out of his apartment and finds a new one, for example, which is another opportunity for reflection. There are virtual tarot readings, offers to go to a nudist space, shenanigans with his cat, recalling and missing his recently-deceased father, and all sorts of observations profound and mundane. At the heart of Budnik’s work, though, is the desire and labor for the possibility of personal change and growth, both as an artist and a person. It’s a journey that doesn’t end, but it’s one where one’s progress can be measured, and Budnik’s output has become more assured as he becomes more comfortable in engaging with the world in such an open manner.

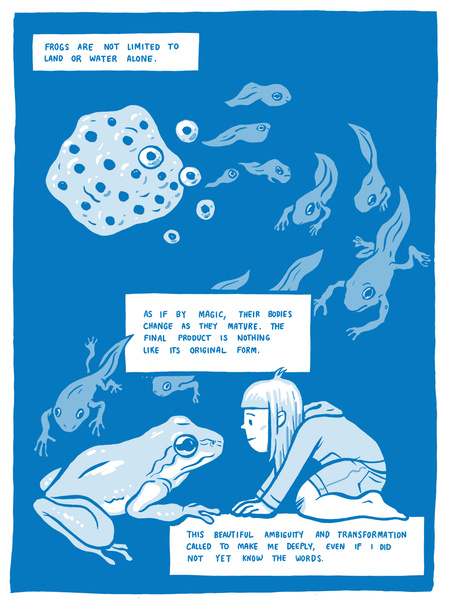

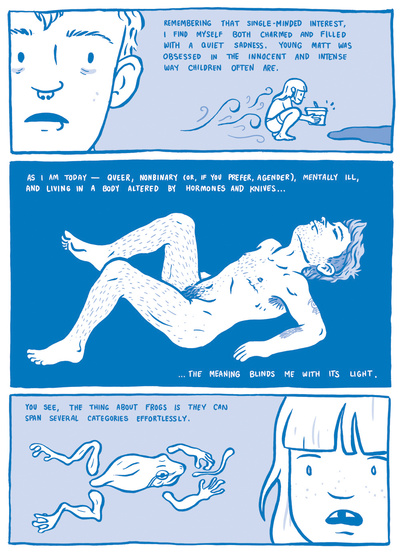

Likewise, transformation and identity are at the heart of M.R. Trower’s beautiful, heartfelt, and relentlessly honest autobio mini Frog. This is all about Trower’s lifelong struggle with gender identity, as they were AFAB (assigned female at birth) but never felt like a girl. Trower uses their lifelong fascination with frogs as a creature whose transformative stages are all radically different as a metaphor for their own journey of transformation, relating it as a journey without a destination as a non-binary person. While they discuss the ache of feeling like an alien in their own body and wishing that they had a penis, they also note that they don’t want to identify as a man, either. It’s the non-binary conundrum, one that butts up against not only cis and heteronormative norms and understanding, but also against many trans and queer narratives.

In telling their story, Trower’s very line transforms and shifts, often from panel to panel. They use a thick line and a cartoony style for childhood scenes, then shift to a finer line and detailed naturalistic drawings as they move into the present. The blue tones throughout the comic are welcoming and warm but also express melancholy. They also contribute to the frequent allusions to water and floating. Throughout the comic, as Trower allows themselves to claim a new identity, they refer back to a new stage of the frog’s development. They go from identifying as straight to bisexual to lesbian (disappointing a partner) to trans, although they never quite fit into a particular label. “I felt like a defective tadpole. Drowning with the dream of coming to dry land somehow always just out of reach.” Though they now identify as genderqueer, they also want hormones and top surgery, and this makes them feel like a defective non-binary person too.

The conclusion of Frog is one of understanding that they can’t choose a gender and focusing on the present as much as possible. There’s a beautiful visual metaphor where Trower emerges out of a pond, saying that they are not only the frog, but also “the water, the earth, and the air.” It’s being all this at once and neither at the same time; it’s understanding that there aren’t always answers. It’s finding a way to be in-between and still accept their fundamental humanity, even if others don’t. This is a deeply warm, immersive reading experience that celebrates Trower’s hard-won acceptance, communicates their journey bluntly and sometimes painfully, and expresses gratitude to those who helped along the way.

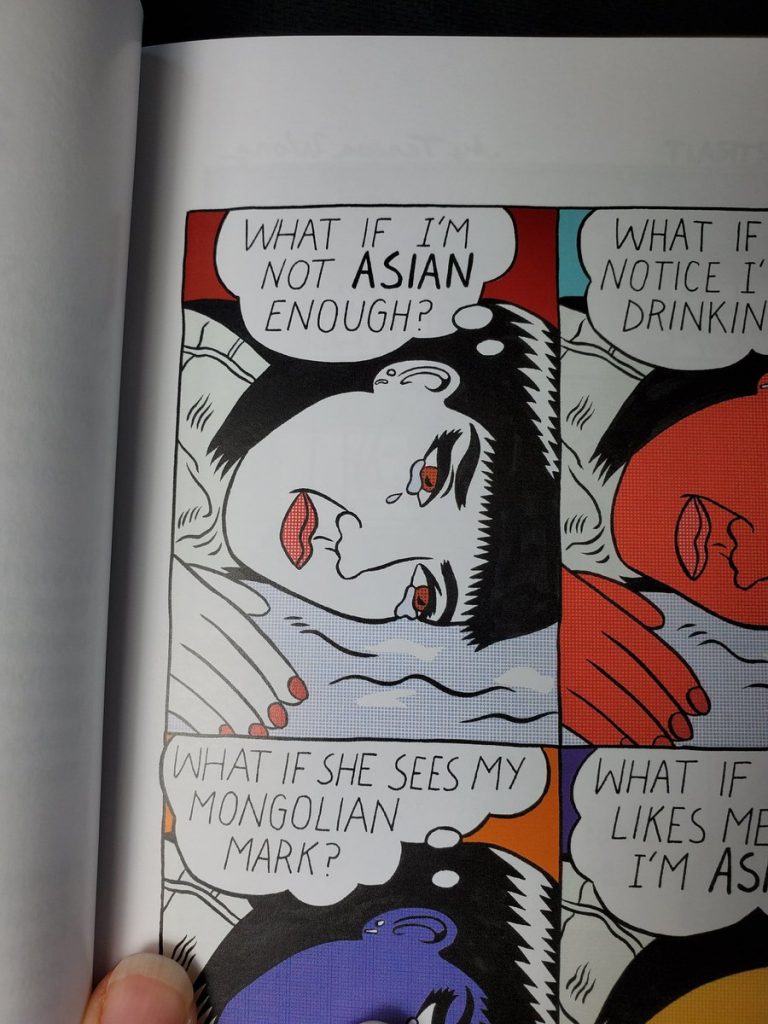

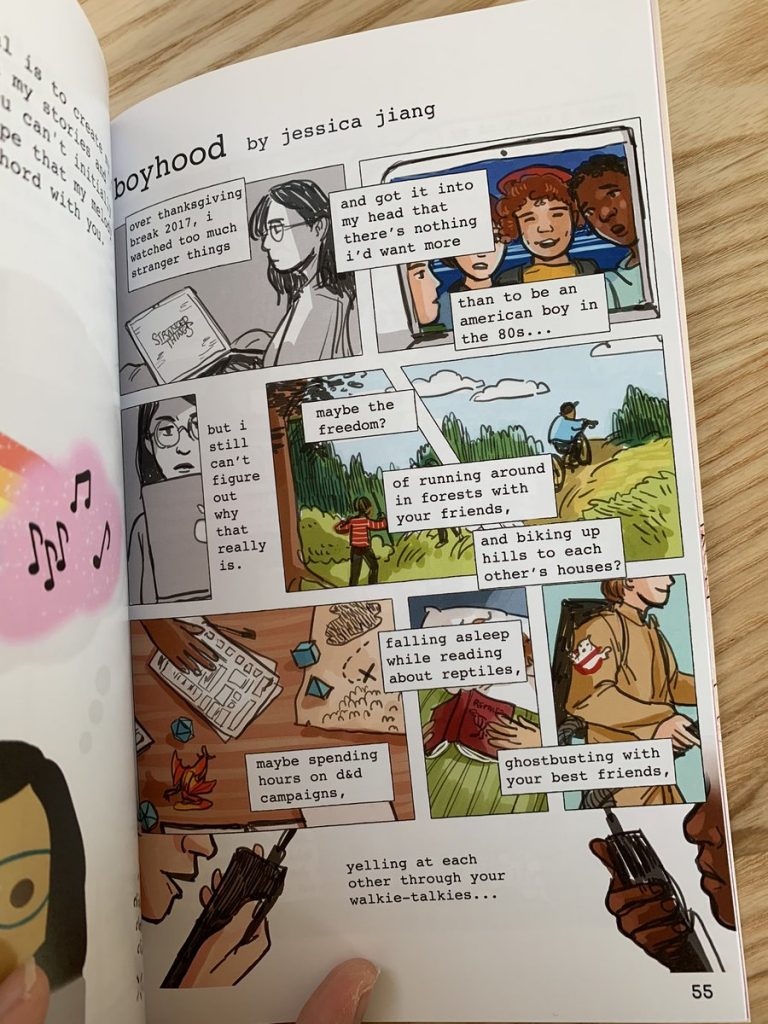

There are a lot of different ways to express identity. Threads That Connect Us is a minicomics anthology that explores racial identity, specifically that of Asians, Asian-Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Though the nature of these narratives differs from Trower’s journey, they are similar in the questions they ask (“Who am I? How do I fit in? Why do people treat me like this?”) and the assertions they eventually make (“This is who I am! Respect me!”). One common thread in the book is that the stories tend to be fueled by long-simmering anger and frustration on the part of the artists but also their pride in family, traditions, and identity.

That’s certainly true for the stories from two of the editors: Sam Nakahira and Filipa Estrela (The third editor, Nhi Luu, did not contribute a piece). Nakahira’s story is about autobiographical comics as her chosen form, discussing the criticism she receives from others for choosing autobio, as well as the perception that she’s almost expected to write about racism because she’s Japanese-American. That hurt is raw, and Nakahira uses a variety of different page design tricks to emphasize different moods, using her voice as an artist to defy stereotypes and make a claim for her right to tell her truth. Estrela, on the other hand, goes in a different direction. She arranges images of bright envelopes decorated with cartoon characters as though they were panels. She used to collect these before she came to the U.S., but she lost all of them when she came here. This story is about using one’s voice and creative skills not just to recreate one’s past, as she skillfully turns these images from her memories into something new as a comics story.

The opening pieces of Threads That Connect Us are by MariNaomi and Teresa Wong, who both tackle the feeling of not being “Asian enough” and self-loathing. MariNaomi’s piece cleverly uses Roy Lichtenstein-style panels to mimic the romance comic-style melancholy that she feels about her racial identity. Wong notes that her self-loathing was so severe that she deliberately removed prominent Asian features in her own graphic memoir. However, her delicate drawings of her children wonderfully express her realization that the facial features she hated about herself she now finds to be beautiful in them. Drawing her children and delighting in their beauty transformed her own understanding of how she thinks of and depicts herself because those are her features too.

Throughout Threads That Connect Us, the artists mourn what is lost, celebrate what is retained or reclaimed, and demand a voice and space for people and cultures that are not often depicted in the mainstream. Eunsoo Jeong’s clever “Koreangry” strips use what look like puppets to create her panels, and it’s an aesthetic that’s a punch in the face. It befits her righteous anger, as she lists grievances not just against obvious racists but also the disappointing frustrations she experiences with her own family and people. Rounding out the anthology is Shirley Pesto who mourns for her loss of speaking Cantonese, even as hearing it is still a comfort for her — a comfort that she tries to emulate in her art. Jessica Jiang talks about her obsession with the show Stranger Things, in part because the concept of having that kind of freedom to go on adventures is both “a gendered and raced concept.” The variety of styles and formats speaks to the incredible diversity even within this group of artists.

Like John Porcellino, each of these artists use autobio minicomics to cross the threshold into a means of self-expression that’s low-stakes in terms of economics and publishing, but extremely high-stakes in terms of its possibility of sparking epiphanies and acting as a therapeutic outlet, serving as an example for other marginalized individuals or groups to emulate. While some of the artists mentioned here also work outside of autobiography (Trower does science-fiction comics with heavy non-binary themes, for example), working in this form gives each of them permission to dig deep into their lives and express their honest understandings in a manner that is frequently poetic, deeply inspiring, and sometimes even confrontational. Their work in this form and their vulnerability expressed through it is a gift to every reader.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply