The most notable things about MariNaomi’s comics are her powerful empathy for her characters and her capacity for forgiving flaws. That extends to her own autobiographical comics, as she not only finds ways to forgive others but also extend that kind of understanding to herself. In her young adult trilogy Life On Earth from Lerner Books, she approaches the fundamental difficulty in human relationships and ethics with the trope of a teen whose disappearance was rumored to be linked to aliens. That difficulty is how unreliable language is in helping us to express our true feelings about things or to feel that we are understood by others. This unreliability results in the fracturing of relationships because our fears and insecurities are amplified by the fact that we can never really know what other people are thinking or feeling. This ultimately leads to isolation instead of community.

The stakes in the book are low and localized, but there are hints that there are ripples that extend across time when toxic relationships, isolation, and mistrust loosen the bonds of society. In the final book of the series, Distant Stars, the aliens that are guiding the formerly missing girl, Claudia Jones, make this explicit. We only see them in a few scenes, including when they are in Claudia’s head, but they are here to intervene in certain relationships in order to help foster love and understanding. Why they’re doing it and the mechanisms behind their mission aren’t important; what is important is that they have a genuine, positive effect on others.

The first volume of the series, Losing The Girl, focuses on a number of friendships and relationships falling apart. It centers around Nigel, a skater who’s also a bit of a player; he’s trying to make a move on his crush, Emily. Emily is involved with Brett, a jock who’s secretly a sensitive artist dealing with a family secret. Their relationship fizzles when she gets pregnant and has an abortion. Emily’s best friend was Paula, but Paula feels like she is taken advantage of too often. The second book, Gravity’s Pull, expands the circle. Darren is Paula’s abusive ex who is furious when he sees that Paula is going out with Johanna, whom Brett loves and considers to be his best friend. Emily rescues her friend Celine from being raped, but Emily can’t stand Paula.

With an easygoing storytelling style, MariNaomi skillfully expands and then contracts the plot threads connecting the characters. In a small high-school community, this intimacy feels natural and earned, as opposed to simply being a plot machination. The second book sees these conflicts heightened and then suddenly relaxed or resolved, thanks to Claudia’s presence. Distant Stars sees every relationship either mended or at least resolved healthily, and that alien intervention really amounts to little more than people opening up to each other.

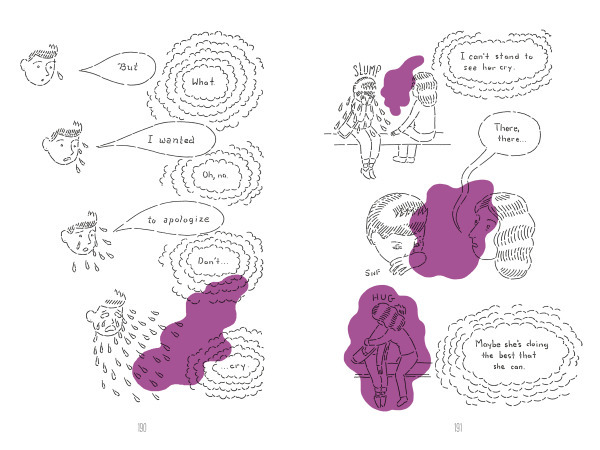

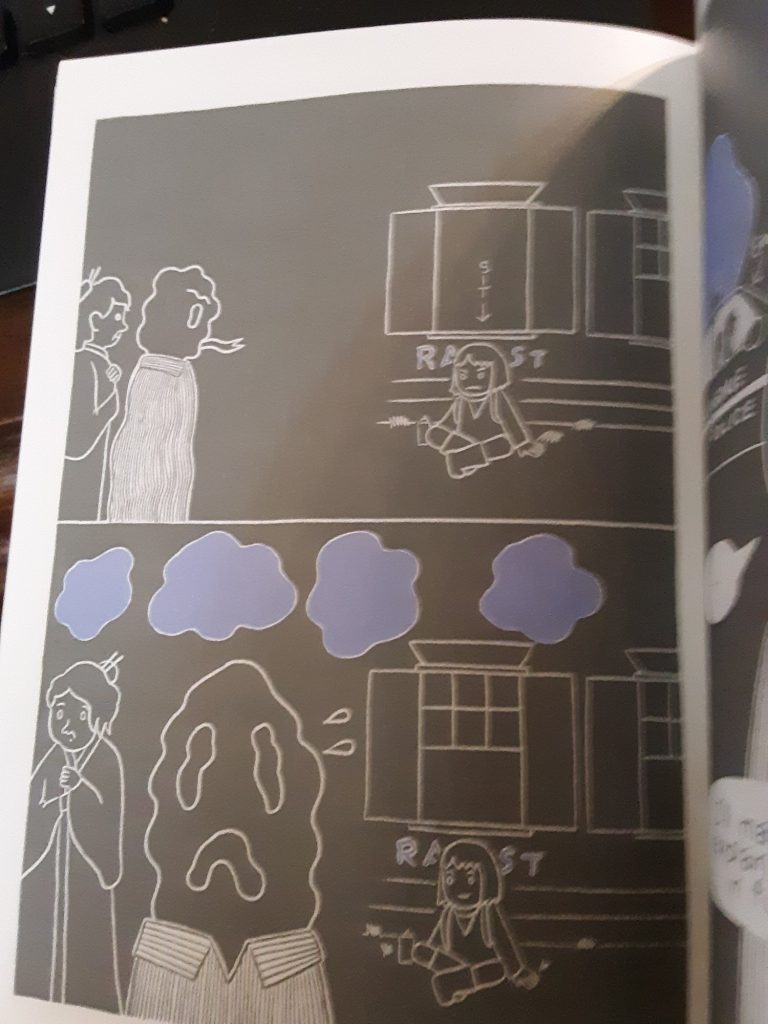

MariNaomi cleverly solves the problem of how to depict different points of view in Distant Stars by literally depicting each character’s narrative differently as a visual strategy. Nigel is cartoony and simple, his dreadlocks sticking out like tubes. Brett is all grayscale and gloom. Darren, reflecting on his abusive father and his own unresolved anger, is nothing but thick black lines. Johanna is nothing but freckles, and her scenes involve some unusual foreshortening. Emily is all about drama and her chapter involves a number of dramatic close-ups. Paula, always a nervous wreck despite her brave demeanor, sees the world and herself in a line that almost vibrates, threatening to dissolve at any moment. Celine’s chapter is perhaps the most clever. She’s feeling vulnerable and immaterial since she was assaulted, and so her self-image is faded and a little childlike. The experience made her regress a little, but her anger is now being redirected to inappropriate targets. When Emily gently nudges her in a different direction, Celine’s self-image and the world around her is sharper and clearer. In each instance, MariNaomi smartly and directly allows the reader to understand that the way we see the world shapes our understanding of reality in a fundamental way. That understanding is inherently limited.

MariNaomi addresses this last point by introducing color into the book. Every story is in black and white…except when Claudia intervenes and introduces warm, abstract colors into the scenes. The colors can’t be seen, but they are clearly felt. Experiencing the colors means different things for different characters. For Darren, it’s a sharp left turn away from violence and into the bumpy process of self-actualization. For Celine, writing out “rapist” in purple on her assailant’s house is a way to literally redirect her anger. For Paula, it’s understanding and forgiving Emily after Emily apologizes to her, finally understanding that her friend was trying her best.

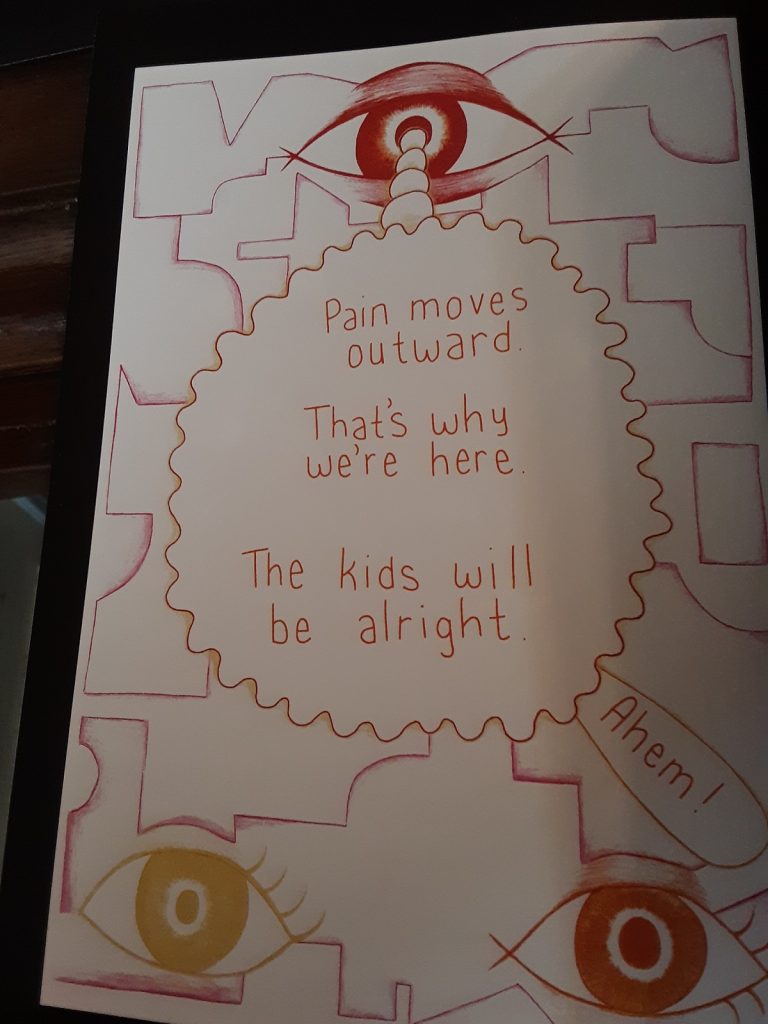

The colors all emanate from “the Claudia Joneses:” Claudia and the two other beings now with her. Once again, the chapter featuring her shows her reading and understanding the thoughts and emotions of everyone around her, and she subtly gives everyone pause as to what they do and say next. She allows everyone to access and express the best versions of themselves. She understands the fragility of human relationships and connections and how ugly words linger and fester.

MariNaomi loves her characters. This doesn’t mean that she wasn’t going to put them through difficult situations. Indeed, the teens in this book go through the wringer. However, she gives all of them a gift in the form of these bonds that the reader can see are being reforged. As Claudia notes (very much in the voice of the author), it could have easily gone horribly awry, but by helping this small group of people, she gives them a chance to build bonds with new people. She gives them the gift of vulnerability and trust. She gives them the gift of forgiveness and forgiving others. She doesn’t make their lives perfect; instead, MariNaomi gives them the tools they need to handle tragedy, heartbreak, and loss. For just a moment, the characters understand what other people are experiencing, and that creates a powerful sense of empathy that will make them want to use their new interpersonal tools. In the end, Distant Stars is ultimately a book about how growth and maturity can only come with forgiving yourself and others.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply