Queer comics are nothing new, but it is pleasantly surprising how normal and mainstream they are becoming. They are now lauded critically and are seen as commercially viable, celebrated as they should be for being able to exist after hard-fought battles in publishing throughout the years. Some recent well-received Young Adult graphic novels that focus on queerness are Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me by Mariko Tamaki and Rosemary Valero-O’Connell, On a Sunbeam by Tillie Walden, Bloom by Kevin Panetta and Savanna Ganucheau, and The Magic Fish by Trung Lê Capecchi-Nguyễn. Another recent addition to the thriving and varied queer YA scene is The Girl from the Sea by Molly Ostertag, released by Scholastic’s Graphix imprint. A colorful fantasy tale about a youthful lesbian relationship, it is a cute-enough ride that unfortunately fails to dig deep enough into the depths of the queer experience. Instead, the seeming avoidance of actual queer conflict ends up leaving the book with a bit of a hollow message.

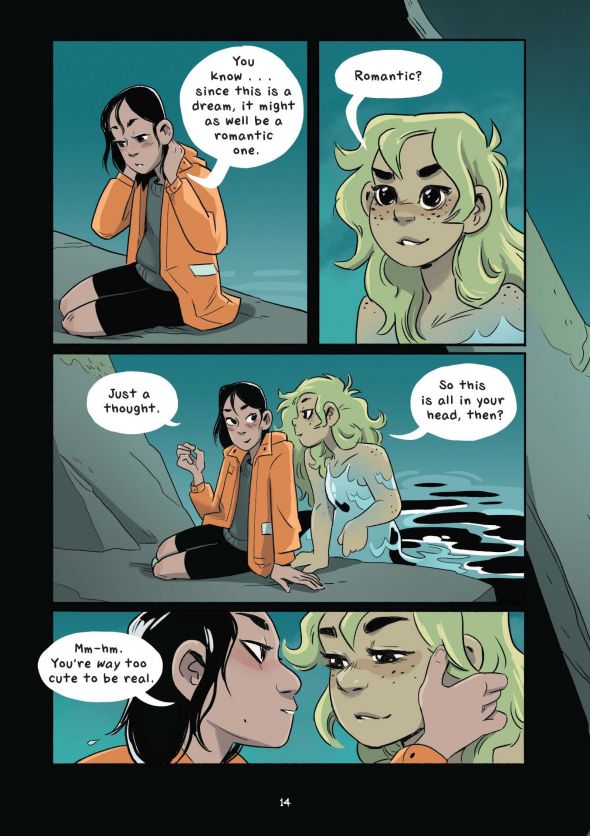

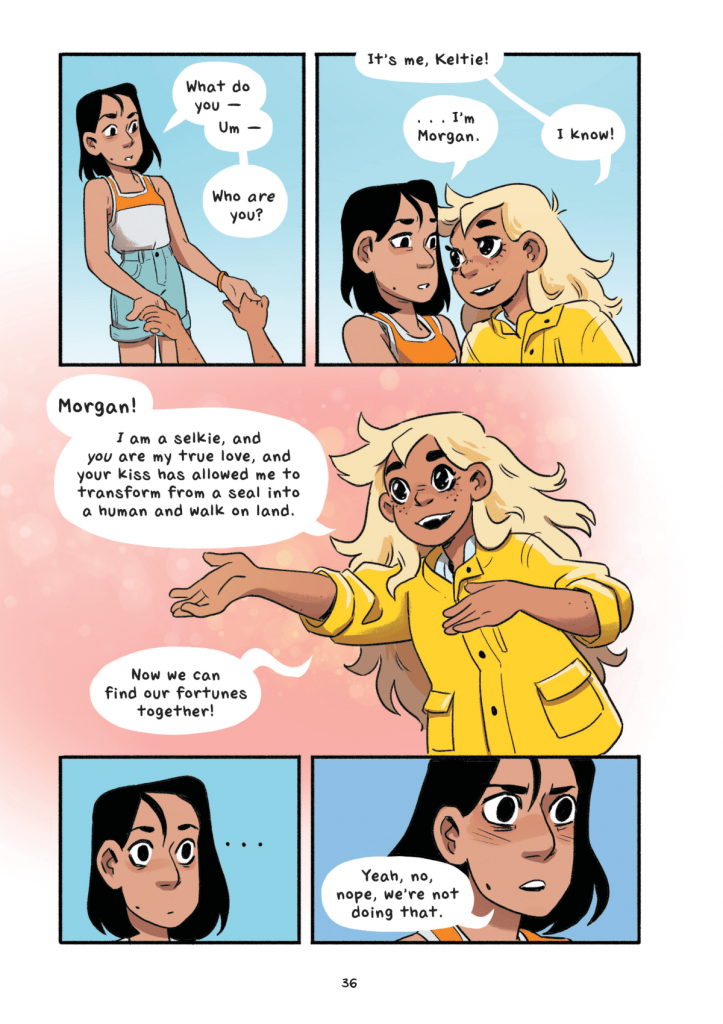

The story starts with Morgan Kwon, a closeted high schooler, falling off a cliff and into the sea one night, about to die. As she reflects upon her last moments, she is saved by a selkie named Keltie, who has taken the form of a human. Convinced that this is a dream, Morgan kisses her, and we are treated to the first time in the story that Morgan allows herself to be honest about who she is. It just so happens that “true love’s kiss” gives Keltie the ability to walk on land, and the two begin a relationship that Morgan struggles to keep secret. For the first half of the book, the plot vacillates between Morgan hiding Keltie, for fear of being outed, and tender moments where they steal each other away to say sweet things (and make out a lot), with the fantasy aspect taking a backseat. Eventually, she has to tell her friends and family the truth about her sexuality, but it is done with a surprising and, to be honest, underwhelming simplicity. This conflict-averse approach seeps into many aspects of the book, and it feels like we only ever scratch the surface of anything that might challenge readers.

This glib queerness is most apparent around halfway through when we reach a boiling point for Morgan; she is outed and forced to come out to her mother. But the fears that dictated her actions and plans throughout the book up to this point are proven to be unfounded by an easy acceptance by her loved ones. Not every coming-out experience is terrible, for sure, but there are usually complicated feelings from both parties that have to be reconciled. Even acceptance comes with a lot of caveats, missteps, and learning. But in Ostertag’s depiction in The Girl from the Sea, there seems to be none, and the only problem with Morgan coming out is Morgan herself.

Part of the issue here is in a narrative sense; there’s no drama. “Tensions” between family and friends are resolved in just a few pages. Morgan’s mom quickly accepts her, declaring that she has “always been an ally.” Morgan’s friends are also taken aback, but quickly congratulate her before moving on with their day. Morgan’s best friend is the only outlier, as she is upset, not because she doesn’t understand, but because Morgan didn’t trust her enough to confide in her. The queerness itself is never the point of conflict in this book, it’s the lack of trust in those close to Morgan. It’s a missed opportunity to delve into the grit of Morgan’s psyche. Rather than dissecting the specifics of why she would not trust her ally mother, nor her heteronormative friends, it’s waved off in the story as a “nobody would understand” type of issue, which feels vague and a little superficial.

I suppose it’s a step forward when a book is not exclusively centered on YA queerness and trauma – and I guess what we see here is an attempt to normalize the coming out experience as uneventful – but, by approaching it this way, Ostertag focuses on every other character but Mogan, and, again, prevents her journey from being emotionally resonant. Queerness is not normalized here; it’s treated as almost non-existent.

This is particularly noticeable because being closeted is the main driving force of Morgan’s character and her most definable quality; she begins the story with a plan to leave the island for “any city”, specifically “to be gay, far away from this tiny town.” We are led to believe that she fears, or perhaps even has witnessed, bigotry, and is preemptively protecting herself. So, when that conflict has been built up so much, it is disappointing, rather than cathartic, when it finally happens. It is important to show queer happiness, and readers who are looking for that will definitely find it here. But the book lacks emotional force because the climax of Morgan’s personal journey is resolved easily and without effort, resulting in it feeling unearned.

Lack of conflict and consequence permeates the book. The main plot after Morgan comes out, which is to prevent a yacht from sailing over a seal rookery, is resolved when someone simply asks about it (off-page, of course). Morgan’s friends and brother think she’s weird, until they don’t, once she explains herself. And what happened to Morgan’s grandparents, who apparently have issues with Morgan’s mom? Is there an implication of culture and upbringing dividing them? Would they have issues with Morgan’s sexuality? The different elements of this book, including queerness and intersectionality, seem to exist in a vacuum, only present for the amount of time that the reader spends looking at it, informed by nothing, with no interior life, and no history.

I have to repeat that queer media should not be focused exclusively on queer suffering. Marginalized creators should not have to or be expected to deal with these issues. But when seeming queer suffering is set up as one of the main conflicts of the story, a lack of nuance can make the themes ring hollow. As a YA book, I think that it could stand to be a bit more challenging, as it is intended for readers who are coming into adulthood and are able to process more sophisticated ideas. And in the grand scheme of comics, it’s hard not to make comparisons to other works that deal with queer themes with a much more deft hand. The manga series Our Dreams at Dusk by Yuki Kamatani (who is asexual and non-binary) similarly deals with coming out, but with much more complex themes of self-hatred, denial, and not being ready to come out. Cheer Up: Love and Pom Poms by Crystal Frasier and Val Wise deals with being trans and how even when people can be supportive, they can still alienate you. Both of those series center characters in high school, but seem to really interrogate the totality of conflicting feelings queer youth have: the desire to be true to yourself, but also the desire to be “normal.” They’re messy, inspiring, poignant, and feel reflective of reality. That’s what’s missing from The Girl from the Sea.

As an Asian-American woman and self-identified lesbian, I really wanted to relate to this story. But everything here just felt too easy, and it never challenged societal expectation nor investigated the complexities and struggles of being queer, which is, ultimately, what a book that sets up queerness as conflict like this must deliver. If your book focuses on queer youth overcoming adversity in society, there’s nothing wrong with making their journey complicated and difficult. Normalizing easy coming-out experiences is great, but catharsis can only be cathartic if it’s borne out of struggle.

“Sometimes you have to let your life get messy. That’s how you get to the good parts” is what Morgan’s mom says after Morgan has come out to her. The trouble is, this book avoids all of the messiness that gay teens inevitably run into as they navigate queerness in a heteronormative world. Ostertag, in this sense, is right: in order to appreciate the good parts of our experience, we can’t be afraid to let our queer stories get a little messy.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply