The thing I admire most about Lewis Hancox’s graphic memoir Welcome to St. Hell is its unassuming style. Hancox has described his aesthetic as “grungy,” and the cartooning can feel rough at times. Yet a reader who pays attention to Hancox’s often sophisticated page designs and paneling choices will quickly realize that his less-than-polished style is deliberate. It’s quite revealing that the handful of online reviewers who have smeared the book as “badly drawn” are clearly motivated by a grotesque ideological opposition to Hancox’s gender identity, rather than a sincere interest in his life or his cartooning. But more on that later.

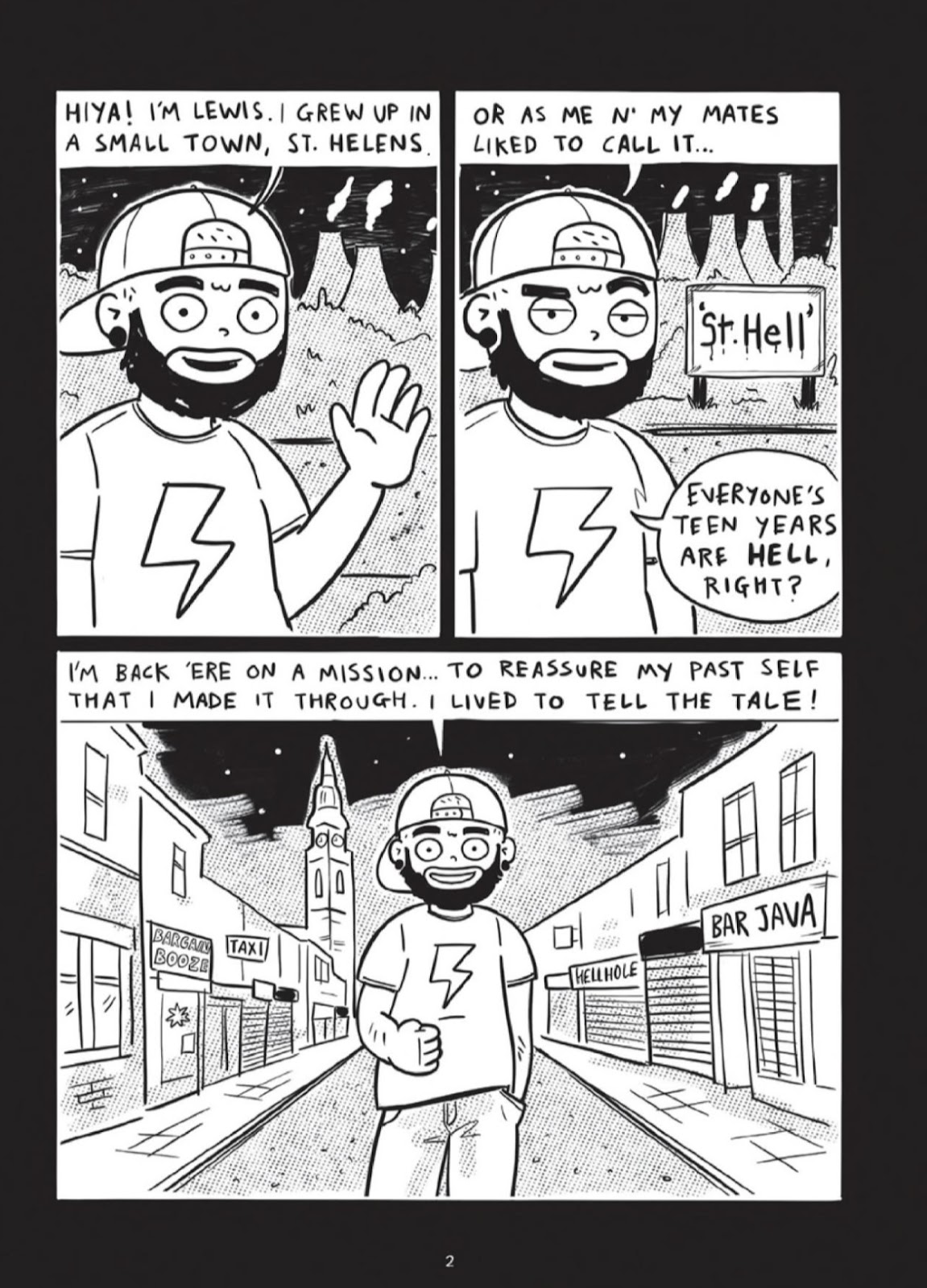

Welcome to St. Hell tells the story of Hancox’s teenage years and his gradual realization that he is trans. While the book is nominally structured as a straightforward chronology, Hancox also orchestrates an imagined dialogue between his younger and older selves: the older Lewis serves as narrator and sometimes as counselor and comforter to teenage Lewis, who isn’t always sure about his own identity but knows he doesn’t feel right being described as “a girl.” These narrative layers are interwoven, but visually distinct, as Hancox signals his older self’s appearances with a black backdrop that overrides the normal white gutters and marks the collision of past and present.

While this is undeniably a trans story — one crafted with the hope that trans teenagers will see something of themselves and find, as the book’s acknowledgments put it, “a cringy sort of comfort” — Hancox is also searching for a larger audience. “This isn’t just a transition tale,” he told Geeks Out. “It’s a journey of self-discovery, whilst trying to fit in at a hellish high school.” St. Hell is a pun on the name of Hancox’s hometown, St. Helens, and it’s the type of wordplay adopted by disaffected teenagers everywhere, the ones who feel trapped by their dead-end small towns. As narrator-Lewis remarks: “Everyone’s teen years are hell, right?”

It’s true that adolescence is a fundamentally uncomfortable experience. Journey-to-adulthood stories are probably the closest thing to a universal narrative structure that human beings have, and Hancox’s storytelling approach is particularly open and inviting. He wants everyone — trans teenagers, cis teenagers, adults of all genders — to read and relate to his story. At the same time, Welcome to St. Hell is punctuated by creative decisions that cut against a simple reading of the text as entirely universal and relatable for cis readers. It is a welcoming book, yes, but it also draws a clear line around the particular pain of growing up as a closeted trans kid, marking the experience as distinct from the undifferentiated mass of “normal” teenage angst.

In one striking sequence early in the book, Hancox depicts his eleven-year-old self as he makes an agonizing choice about gender presentation: Pants or skirt? It’s a wardrobe binary that narrator-Lewis describes as “a decision of doom,” a phrase that sounds melodramatic but reflects real psychological and social stakes. Teenage-Lewis wants to wear pants and wants to look like a boy but is scared of being found out and mocked. In the end, there is only one choice: to wear the skirt and pose as a “real girl,” no matter how false and uncomfortable that identity feels. Yet the cruel irony is that wearing a skirt isn’t enough to help Lewis fit in. In a situation that inverts his original anxiety (i.e., wearing boy’s clothing but being outed as a girl), his schoolmates single him out as “a boy in a skirt.” While narrator-Lewis remarks that the observation is true (“I was a boy in a skirt”), the taunt is an act of bullying.

It’s a moment with the potential for broad relatability, especially for anyone who has ever been mocked for their appearance. Who wouldn’t feel embarrassed, as Lewis does? But Hancox uses the comics page to tease out the particular — that is, trans — subjectivity of his younger self’s discomfort. His panels literally bisect teenage-Lewis’s body: In the page’s upper half, his head and torso are surrounded by his derisive schoolmates, while his skirt and legs are isolated below in a separate panel. It’s as if the markers of Lewis’s blurred gender identity are literally fracturing, his short, boyish hair splitting away from his “real girl” skirt. The natural reading order of the page further emphasizes the break. Our eyes want to move, not from top to bottom, but left to right where, in the page’s second panel, Lewis’s friend Jess shoots back at the bullies on his behalf: “Piss off! She’s a girl!” (While well-intentioned, Jess’s comment seems to inadvertently reinforce Lewis’s dysphoria in the moment.)

The tricky balancing act that Welcome to St. Hell achieves as both a broadly appealing coming-of-age memoir and a specifically trans story is, I suspect, why it has been viciously attacked by transphobic hate movements. After the book was shortlisted for a 2023 Waterstones Children’s Book Prize in the UK, a wave of review bombing and a petition to remove the comic from consideration for the prize both followed. The far right is, of course, doing its best to eliminate all LGBTQ comics from public life, but the precise nature of the deranged responses that Hancox’s comic has attracted is worth its own scrutiny.

Perhaps the most striking attack came from a transphobic activist on Twitter, who photoshopped a key page on which Hancox draws a “map” of his pre-transition body. The original is a vulnerable, uncomfortable image that, among other things, describes his breasts as “fatty lumps that need to be gone.” But this Twitter user mutilated Hancox’s work by imposing their own warped vision of body positivity, replacing his uneasy descriptions with cheerful, cringeworthy messages (breasts are “normal and useful”) and denigrating his experience of gender dysphoria as the product of “uncaring people … telling [him] there is something wrong with [his] body.” This transphobe even went so far as to visually edit Lewis’s expression, changing an anxious face into a smiling one.

The vandalism follows from a flawed assumption: Namely, that the image — and Welcome to St. Hell as a whole — will influence young girls to hate their own bodies. That is, at best, a willful misunderstanding of what Hancox is doing; I read the page in question as a clear attempt to convey the visceral, physical anxiety he suffered from growing up in the wrong body. But to actually rewrite the text represents more than just a misreading; it’s an aggressive and invasive act. It’s also a reminder that censorship is never merely an act of erasure. There is always a message to replace what’s been silenced. In this case, the message is this: that trans kids’ experiences aren’t valid; that their feelings are false and manufactured by malicious actors; that they must force themselves to fit into bodies that cause them pain.

Hancox, of course, is articulating precisely the opposite message. Artistic talent alone isn’t going to win the fight for trans liberation. But it does give me hope that a well-crafted book like Welcome to St. Hell exists, while the best transphobes can do is react and scream and photoshop their propaganda onto a comic none of them are skilled enough to create.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply