The only thing I enjoy more than listening to rock-and-roll is watching films or reading books and articles about rock-and-roll bands. Give me a basic cable subscription, an idle afternoon, and Jim Forbes narration and I’ll be your huckleberry. Like the barbaric yawp that was VH1’s “Behind the Music,” Koren Shadmi’s All Tomorrow’s Parties takes a cradle-to-grave approach to the Velvet Underground. Unfortunately for Shadmi, he’s working in a medium in which the restless feelings ginned up by Forbes’s tease into commercial breaks don’t translate and so what results has, at times, all the charm of a Wikipedia entry. Only when Shadmi goes off script into cubby holes, cold water flats, and derelict piles does this sick and dirty story swing with a sort of big straw hat swagger and a dissonance – appropriate to the Velvets – from an otherwise cliched cookie-cutter rapturous rock doc. TV show of the late 90s and early 00s. Ask Mort Todd, he of the defunct 90s imprint, Marvel Music, music comics are, unfortunately, like so many Sunday clowns.

Critics, sycophants, and normies have tried to pigeonhole the Velvet Underground since their infamous debut, The Velvet Underground & Nico splashdowned. And yet the Velvets are – will always be – (almost) too offbeat to be accepted into the mainstream which is the appeal. The Velvet Underground is from the street, a bunch of weirdo pioneers establishing a hand-me-down colony in the straight world.

To wit, it’s hard to find any one thing in popular American culture or history that augurs the Velvets. Perhaps the only pop culture ephemera that comes closest is a line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the one that goes, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” As it slouched out of the swampy bayous, cotton fields, and dusty crossroads of the American South towards an undetermined Bethlehem, rock-and-roll and myth making have gone hand in shiny-shiny leather glove.

Only in recent years as more sober and hip artists, academics, and critics have begun to revise and unpack the love and theft central to the historical record that makes rock-and-roll rock-and-roll have its originators i.e. African Americans began to receive their due. To borrow from Herman Melville, another journo and myth-maker, pop culture’s rock-and-roll icons, the white ones, mostly, are – “as pasteboard masks.” The rhythms laid down by boogie-woogie, gospel, blues, and country music are the different colors of tears in the paintbox of rock-and-roll which, for the Velvet Underground, are but streetlight fancies. And yet, and yet, the Velvet Underground remains (somewhat) aloof in the historical record, they remain on the margins, idiosyncratic, singular, and still their influence remains (ahem) legendary. It’s here where, cribbing from the Wikipedia entry for the debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico, the requisite Brian Eno quote, which was actually said by Lou Reed to Eno in conversation enters the chat: “while the album only sold approximately 30,000 copies in its first five years, “everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band!”

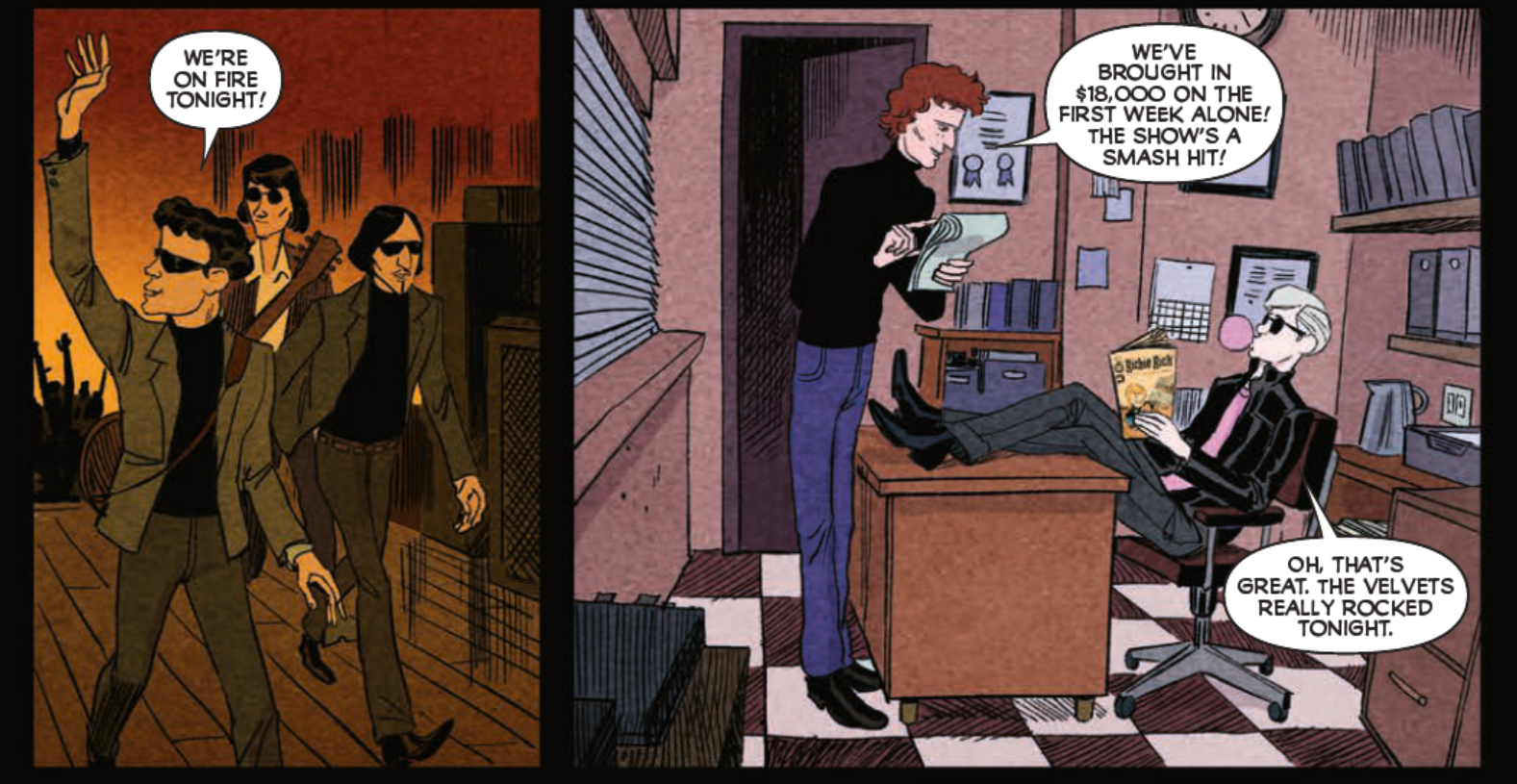

Like the members of the Velvet Underground themseleves, Shadmi’s All Tomorrow’s Parties embodies the idiom of “too clever by half;” however, it’s not nearly as scrappy as its subjects or their story and that’s the rub. Here is a rock-and-roll outfit of castaways and cut-outs managed by Andy Warhol – raconteur, workaholic, visual artist, and film director – during rock-and-roll’s adolescence. Warhol and the Velvets stood at that well-trodden crossroads of art and commerce like no one before. To go further, it was kind of his “thing.” Add to this Warhol’s chumminess with the market and you’re talking about an unmatched cultural exemplar of the 20th century. Not since the dynasties of the Borgias and Medicis has patronage been as important or influential. Would there have been a Michaelangelo without Lorenzo de’ Medici? Like those Middle Age kingmakers, the Velvet Underground was, for Warhol, yet another project in an assembly-line-like set of projects (printmaking, painting, film, etc.), another way to tap into the zeitgeist which Warhol craved and abhorred in equal measure especially if it could be exploited. VU fit into his bigger project which was, as always, Warhol himself writ large.

And so Shadmi chooses to begin his examination/exhumation of the Velvets at the end: the death of Andy Warhol on the island of Manhattan on February 22, 1987, to be precise. Shadmi understands there’s no Velvet Underground nor its subsequent legend without Warhol and, so, his end is the beginning. And here’s where Shadmi’s intentions get off on the wrong foot from the jump. Shadmi’s choice to hover over Warhol’s bedside like some visitor from night’s Plutonian shore as he expires while accurate to the ontology of the Velvet Underground’s story it is pedestrian and hokey – descriptors never applied to the band itself – and yet this image of a bald Warhol may be what Warhol pursued in his art, to make an audience revel and reflect on the beauty of the mundane and monotonous mixed with a black angel’s death song.

Warhol’s demise allows Shadmi to unfold his hagiography amidst one of life’s more painful and anxiety-ridden experiences: a reunion of parted lovers, in this instance, at the funeral for a friend. Our former paramours are Lou Reed and John Cale, if you (didn’t) know, you know. For better or for worse, Reed and Cale’s relationship is the story of the Velvet Underground and the Velvet Underground is Reed and Cale’s story with Warhol serving as some initiating force. Reed and Cale are the Romulus and Remus (another set of legendary myth-makers) of the Rome that was the Velvet Underground with Warhol in the role of the she-wolf. From Warhol’s funeral in ‘87, Shadmi travels back to ‘59 to the Welsh row houses and Long Island suburban cul-du-sacs to check in with Cale and Reed, respectively. Again, for Velvet Underground-ologists, this is so much well-trafficked ground it might as well include a radioactive spider or murdered parents. I would never number myself among those VU superfans (more of a tourist), but the next time I see, read, or hear a re-telling of poor Lou being strapped down and administered ECT in its most primeval and least humane state will be too soon. Same goes for Cale’s Welsh upbringing riven with alcoholic/absent adults and suicidal struggles.

As with all similar approaches to slavishly adhere to “the record,” the windup is part of the tedious ritual of such narratives. For those readers who don’t know Reed cut a goofy, novelty song, “The Ostrich,” or Cale’s obsession with John Cage’s avant-garde approach to music which spurred Cale’s further travels down the rabbit hole of Eastern drone, mazel tov. Slogging through all this Velvet’s juvenalia one wonders when Shadmi will allow a glimpse at the proverbial (fireworks) factory.

Of course, that blessing is bestowed in due time when Reed and Cale – fresh from their earliest forays into heroin experimentation while living their somewhat-romantic lifestyle with fellow vagabonds-in-residence amongst the penury of Manhattan’s Lower East Side circa the early 60s – encounter Warhol which allows them entrée into “The Factory.”

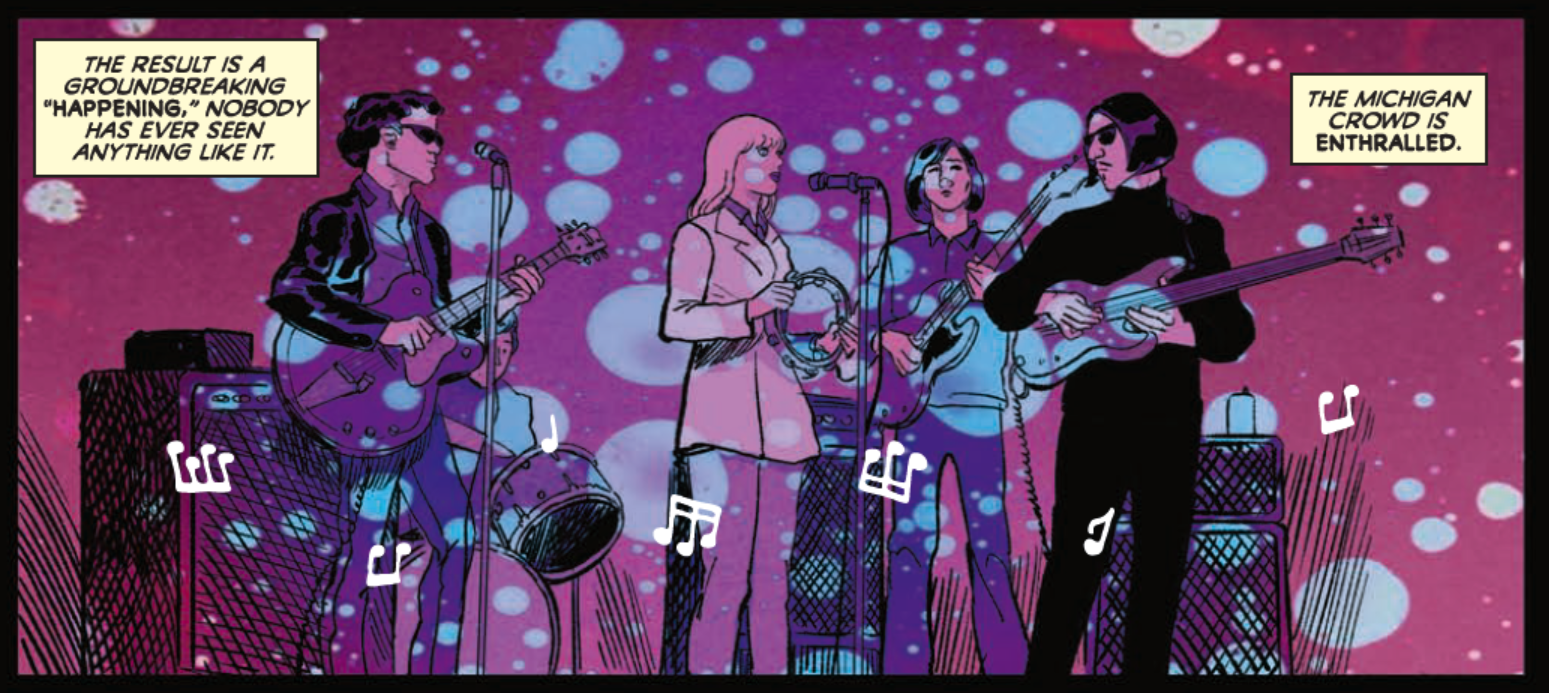

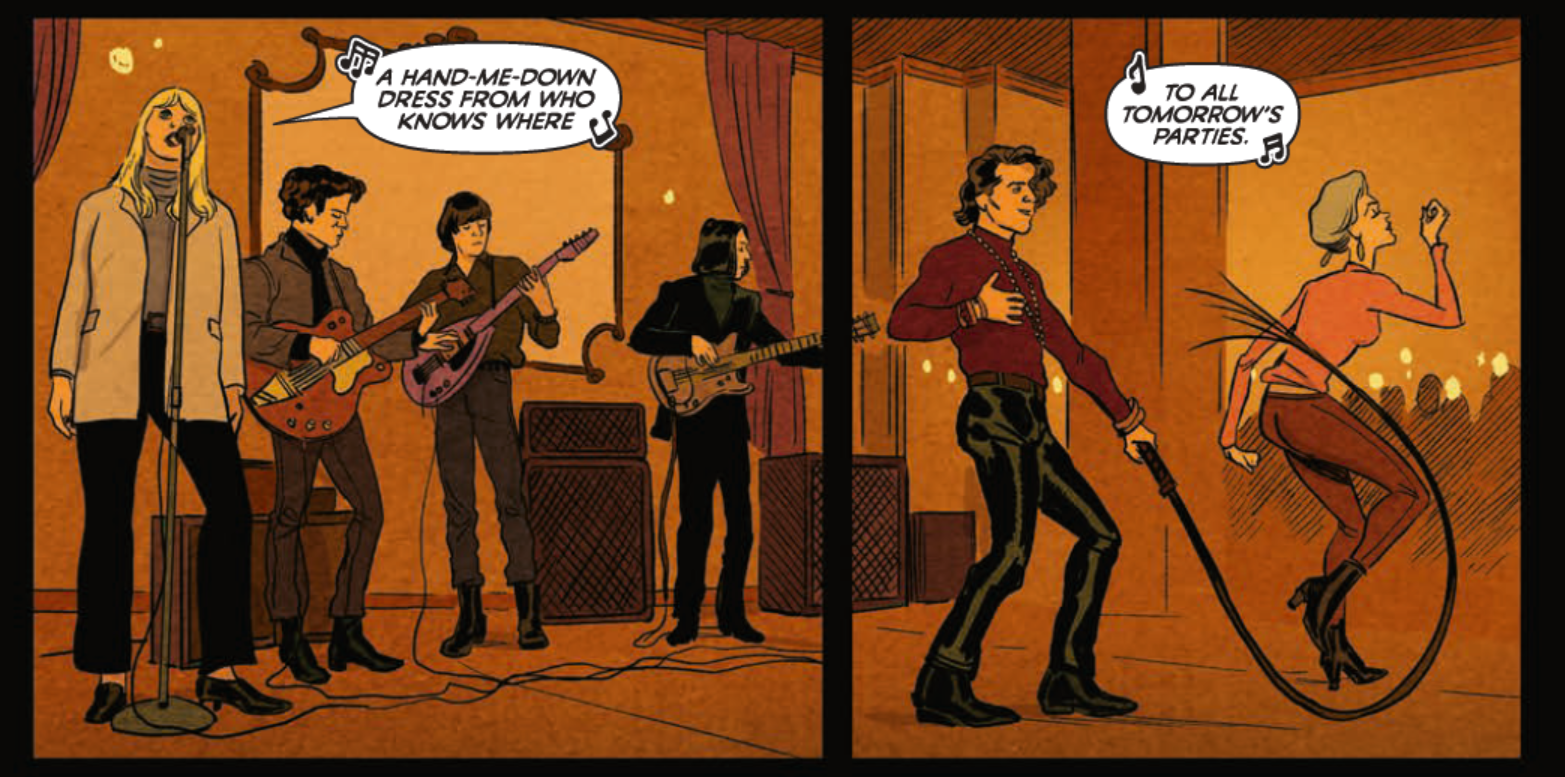

Show me a band that is tight but loose when they perform and I’ll show you to the woodshed. Taken from its rural roots, “woodshedding,” is how jazz cats and early bluesmen with names like Pinetop and Furry honed their craft. And it’s how any artist, rock-and-rollers included, reach their ten thousand hours – to borrow from that old chestnut, “how do you get to the Exploding Plastic Inevitable? Practice. Practice. Practice.” Seeing a half note or demisemiquaver floating mid-air beside a drawing of someone holding a guitar or a raking a bow across a violin or the lettered “Toom Toom Toom” of a Moe Tucker drum fill comes across as ersatz, weak sauce, a blackened shroud. But if you’re telling the tale of a band, especially one like the Velvet Underground, what shall a poor girl wear, to coin a phrase?

In the backmatter of “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” Shadmi includes his process work, a personal essay, and, appropriate to his project, a bibliography. What those non-fiction sources can’t account for is what the “behind-the-music” and other such shlock leaned into with abandon, the re-enactment. What are, I’d reckon, private recollections of conversations, personal memories, or peripheral glimpses gleaned from those Velvet Underground biographies are when Shadmi shines.

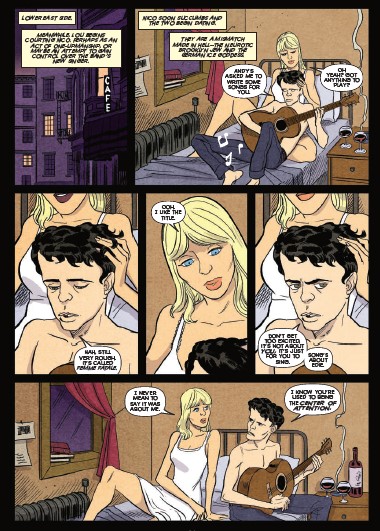

Such as his (re)imagining Lou and Nico holed up in some Lower East Side apartment. He draws Reed like the crucified Christ draped across Nico’s slim fawn-like frame like some proto-punk pietà as he plinks and plunks through, he says, “a still very rough” Femme Fatale. This moment juxtaposes a similar transactional conversation that occurs on the previous page between Cale and “it girl” Edie Sedgewick. Shadmi captures the spirit of each of these titanic personalities without having to rely on actual events. By showing, not telling, an intimate romantic moment, Shadmi draws out Lou’s ire, paranoia, and contempt for Nico and, perhaps, all human existence – a nihilist worldview Reed cultivated, cherished, and celebrated throughout his life – it’s no secret Lou loathed and didn’t dislike Nico and all she symbolized, but no one who could produce “The Marble Index” was as phony or untalented as Lou and Nico’s detractors claim. When it comes to Nico, Lou knew it when he wrote it, “you’d better watch your step.”

The song “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” from which Shadmi borrows his title, is a pipe dream of a Cinderella story, a paean to be included, to finally be a part not apart. The character in the song wishes for something that may never and, cynically, won’t ever happen and, if it does, it will only end in a hand-me-down gown stained with the tears of a clown. Acceptance is ephemeral, always fleeting, ask the Velvets. Unless, of course, like Warhol, you make it yourself. That’s where one finds The Velvet Underground, in liminal space, neither fish nor fowl. Shadmi’s work is in attendance – a part, but sadly, not apart – at those mythical future fêtes. Perhaps “I’ll Be Your Mirror” would have been a better song title to ape, to tell this legendary tale, perhaps, perhaps.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply