On the one hand, it’s hard to believe that Johnny Ryan’s notoriously — and deliberately — amoral gross-out comic Prison Pit was nine years in the telling, running in semi-annual single “issues” from 2009 to 2018. After all, it’s seldom, if ever, that these sorts of “extreme” narratives are anything other than short strips — it’s rare that they run even the length of a standard 32-page comic book, much less end up becoming 700-plus-page epics, and there’s good reason for that: a visceral gut-punch tends to have more impact than a series of body blows that the recipient (in this case, the reader) becomes inured to over time. On the other hand —

if there’s one cartoonist who has proven that he can fairly consistently “one-up” himself when it comes to sheer depravity, it’s Johnny Ryan, who’s literally made a career out of dreaming up one “politically incorrect” grotesquerie after another. As such, his work has (entirely understandably) polarized audiences almost from the outset, not only because of its inherently rancid nature and subject matter, but because while he certainly hasn’t changed much, the reading public has. In point of fact, the racism, sexism, and homophobia that oozed from the pages of Ryan’s earlier series, Angry Youth Comix, are now generally acknowledged to be no laughing matter, and their historical prevalence in the underground and small-press comics of the past is something that’s now actively being grappled with rather than simply swept aside as a product of their times. All of which is undoubtedly a good thing.

This may not, however, simply be a “one hand or the other” situation. I would posit that there is a third thing to consider, and that is that there will probably always be that class cut-up cartoonist, the kid who sits in the back and doodles all kinds of gross-out illustrations in his notebook. Crude, unsophisticated, borderline-blasphemous shit that he uses to get attention or elicit a reaction, even if that reaction is just “dude, you’re sick.” And while, yes, it’s true that this kind of cartooning isn’t objectively “good,” there’s often an undeniable energy to it, an intensity that one only finds in stuff that’s coming straight from the id, through the pencil or pen, and onto the page. Chances are that Johnny Ryan was that kid in high school — and while the rest of us went and grew up, he simply got a lot more focused on what he was already doing.

Now, lest I come off as somebody who is in any way opposed to free creative expression, I should state for the record that being forced to face up to the ugliest aspects of human existence is a vital and necessary thing. Where the entirely valid criticisms of Ryan’s work have a point, though, is when they state that there’s been no real indication that he’s exposing the idiocy of racism, sexism, or homophobia for examination, rather, he’s simply playing these “third rail” subjects for cheap laughs at best, or giving a tacit “okay” to them at worst.

I’m of two minds on this latter opinion, but I generally agree with the former. Back in the dim and dusty past, when Prison Pit was initially solicited as his take on hyper-masculinity and ultra-violence, I was expecting a shift of venue away from the strip malls and suburban squalor of Angry Youth Comix, but not of tone. And while the exploits of ‘roid-rage protagonist Cannibal Fuckface –I’m going to give Ryan the benefit of the doubt and assume the C.F. initials are either a total coincidence or an inside joke that the cartoonist who uses that pseudonym is cool with — fighting to survive, and to make sure anyone and everyone else who crosses his path doesn’t, in the permanent intergalactic battle royale that the book takes its title from are, in fact, no different than what one would surmise them to be going in, the tone is very different, indeed.

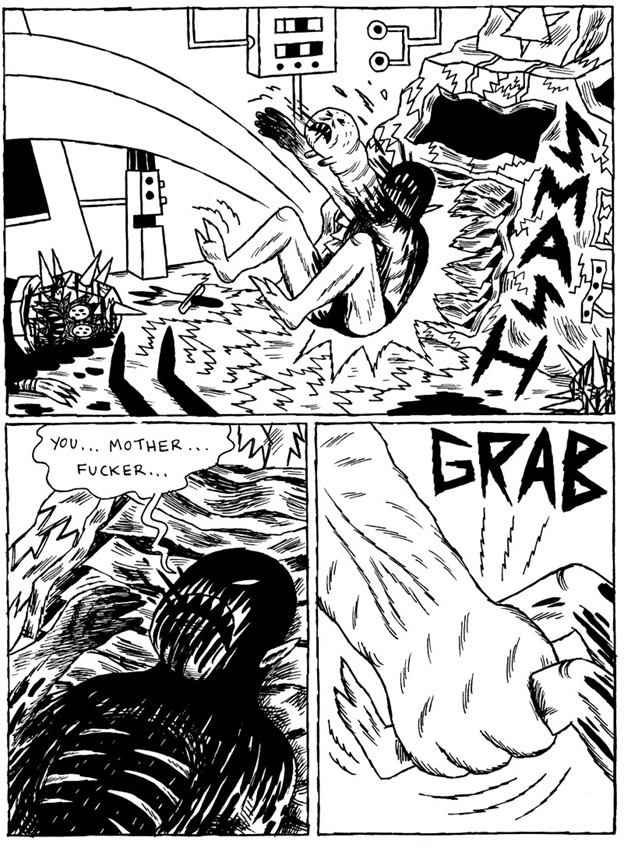

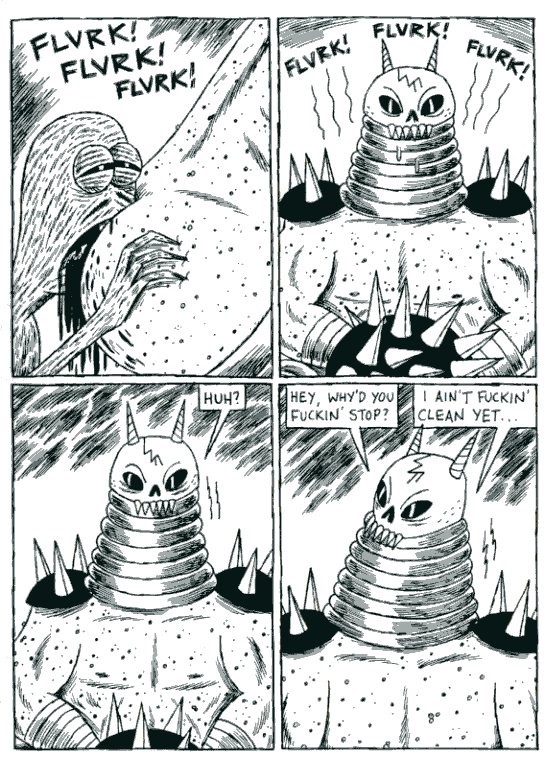

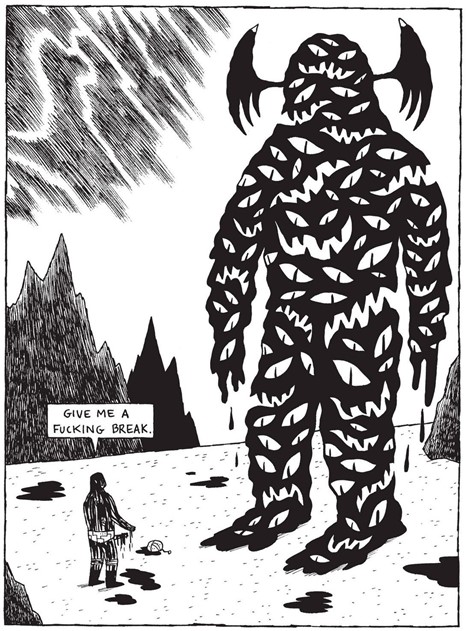

Granted, this tonal shift takes some time to register, and is more noticeable when the work is consumed as a whole, as in Fantagraphics’ just-released compendium edition, than it was in single volumes spaced 12 or more months apart. Frankly, when read in “singles,” the first few, at least, come off as little more than mindless splatter-fests, but by the midway point, a kind of forlorn resignation to the depths one must sink to in order to get by in the most inhospitable environment imaginable, coupled with a deep nihilism that actually makes narrative and philosophical sense, all things considered, really does register. I mean, if you knew that every fight to the finish you had with an alien robot or monster or warlord only meant that you lived to fight in one more, well — sooner or later — that would get to be a real bummer. And while Ryan’s pen illustrations do, in fact, retain that kind of “class cut-up” energy mentioned previously — complete with requisite crudeness — his facility with expression is communicative enough that he’s able to stamp this point of view into most of the proceedings even with only a very minimal (and minimalist) assist from his threadbare dialogue. Any one of those class cut-up kids scribbling in their notebooks or on their desks can delineate a kick-ass battle scene — not many can show how much it absolutely sucks to find oneself in one after another after another.

This being a Johnny Ryan book, of course, none of this is particularly subtle — but that absolute lack of subtlety actually pays dividends in the end, when Cannibal Fuckface, having finally vanquished Slitt, the warlord he believes responsible for all his misery, comes face-to-face with the shadowy “power that be” that fashioned him into such an unstoppable homicidal force in the first place and is offered a choice between complete and total freedom, the life of his dreams, or destroying the entire universe just to get revenge on his keepers. You probably already know when option he selects — and if you don’t, I’m not going to be the one to give it away. While there’s no particular pathos at play as C.F. makes his decision, there is pathos aplenty to be found in the fact that there is no pathos. There was never any choice, never any doubt, and there’s little by way of any hesitation on his part — but rather than portraying this as something either stupidly hilarious or, in a pinch, simply just “fucked up,” Ryan shows it to be a tragic inevitability, his “hero” reduced to a hollowed-out shell thanks to a lifetime spent doing nothing but killing.

It’s a painfully obvious point made by painfully obvious means — Ryan drags it out for several pages — but by this point, anything less than clobbering you over the head with it would feel inherently dishonest. Prison Pit is all about sickeningly juvenile excess, about depravity for the sake of depravity and nothing else, but at least Johnny Ryan is prepared to admit there’s something not just wrong, but downright sad about that. As such, this isn’t a book that’s shocking for its brutality and its immaturity, but for its — thoughtfulness? And yeah, I can’t believe I just typed that, either.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply