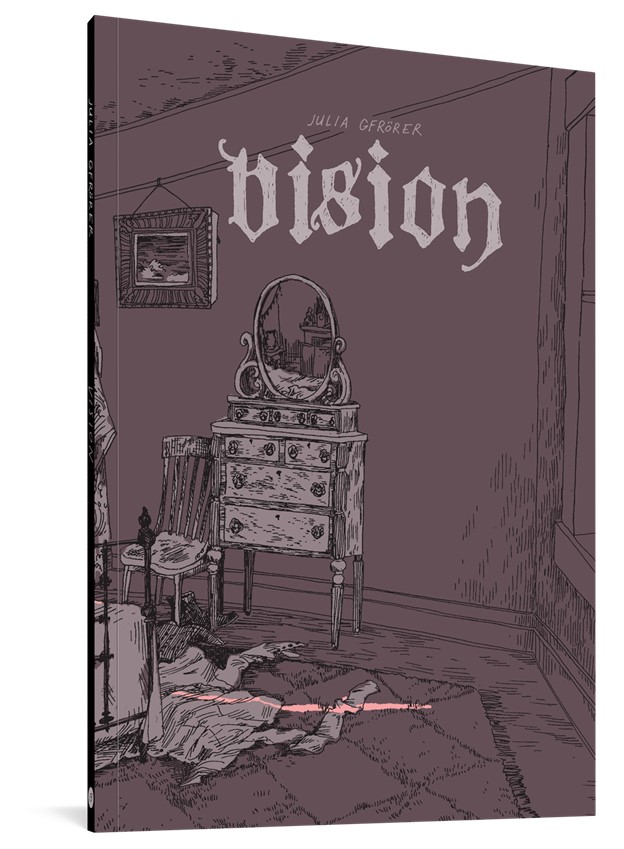

Julia Gfrörer is one of the most exciting cartoonists working today, applying her elegant but raw linework and sparse, immediate dialogue to stories that focus on very particular themes and concepts that she’s come to establish as her own, and which I’ll allow her to expound on herself rather than doing the disservice of attempting to address them in advance. Suffice to say, she is the very definition of an auteur, and I heartily encourage anyone who hasn’t done so yet to check out her comics. I spoke with her on the occasion of the impending release of her new book, Vision, her third with publisher Fantagraphics, which may offer the most conceptually tight examination of the subjects that inspire and haunt her in equal measure to date. Many thanks to Julia for her time, and to Jacq Cohen for making the initial arrangements. To have a look at more of Julia’s work, including items she has for sale, please visit http://thorazos.net/

Ryan Carey for SOLRAD: First off, the basics — how long have you been cartooning, and what attracted you to the comics medium in the first place?

Julia Gfrörer: I confess I’ve never been much of a comics reader. My BFA is in fine art. What won me over to the medium was that my ex-husband and I moved to Portland in late 2007, and almost everyone we met in the art community was also involved in comics in some way, and when they found that I could draw they encouraged me to join them there. I guess you could say it was peer pressure? At least that’s how I remember it now, after the fact—this all seems like a lifetime ago.

Carey: Your three books with Fantagraphics are all “of a piece” in terms of publication design, paper stock used, etc. Are you involved in that end of the process? I ask because, aesthetically, the format for your books is very much “pitch perfect” for the types of stories you’re telling.

Gfrörer: Thank you! The book design is a collaboration between myself, my editor Eric Reynolds, and Fantagraphics’ in-house book designer Paul Baresh. As a bookmaker myself, there were certain things I wanted: uncoated textured card stock for the cover, a wraparound cover design (most of my zines also have wraparound covers), black endpapers, and natural-colored interior pages. I think the French flaps were Eric’s idea. We came up with that design for Black Is the Color back in 2013, and it worked pretty well, so we stuck with it.

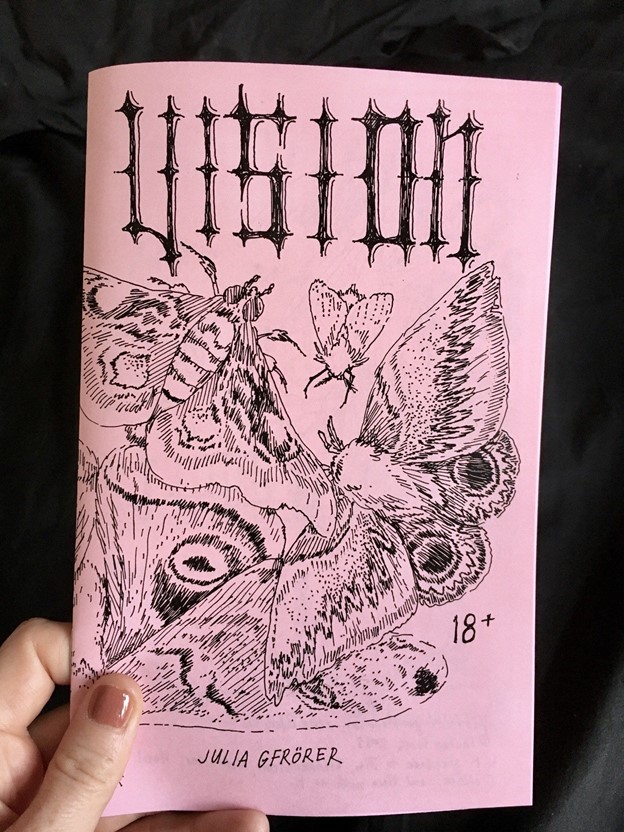

Carey: You’re also a fairly prolific self-publisher, and Vision, in fact, started out as a series of self-published minis. Is self-publishing something you intend to continue doing for as long as you’re able?

Gfrörer: Of course! I love Fantagraphics dearly, but there are certain aspects of self-publishing that are always preferable. Zines are very cheap to produce, and immediate—if I have a stack of drawings, it only takes a few bucks and a couple of hours in front of the copier to turn it into a book. A book for a publisher will have been completed for a year or more before it’s released, and I have no patience and can’t plan ahead to save my life. I can finish drawing in the morning and be selling copies of the finished zine the same afternoon (I’ve done this for conventions more often than I like to admit). I can charge less for zines, and they’re less precious. A zine is ephemeral, it’s not made to last forever, and I like that. I’m uncomfortable with the book as an art object. To me, a book is just the box a story comes in.

Carey: Moving from medium to message — horror. I think it’s fair to say most of your work falls within the loose parameters of that genre. What is it about horror that draws you to it as an artist, or don’t you feel your work to be “horrific” or “horrifying” at all?

Gfrörer: Oh, I think it’s absolutely horror. I would call it pornography, too. Why my work is like that is a difficult question for me to answer, because I don’t exactly choose what kind of stories I write. In my brain there’s a faucet, it’s turned on most of the time, and I hold a bucket under it and catch whatever I can, but I can’t really control what comes out. I’m attracted to stories of people in extremis. I’ve never had the kind of depression that manifests as lethargy or anhedonia. Even my suicidal urges were always passionate, almost ecstatic. Horror stories feel more true to me.

Carey: Black Is The Color was set, if I’m not mistaken, in the 17th century, while your newest, Vision, is set in the Victorian era. Is this a conscious choice, this sort of moving forward in time, and do you foresee setting your next book nominally even closer to present times?

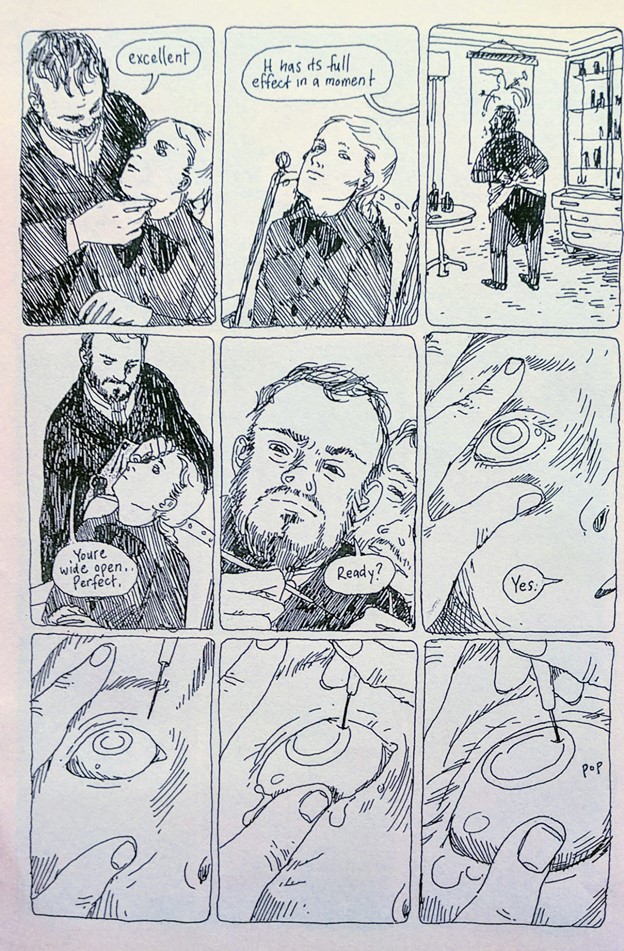

Gfrörer: Black is the Color was the earlier book. The era in which the story is set is dictated by what it needs to do. Vision is set in the late Victorian era (though in America, so not precisely “Victorian”) because I wanted to include a certain type of spring-loaded fleam or lancet, and that was the time period when such things were in use. A lot of the story was shaped to accommodate the fleam. But also, it is a story which self-consciously references Gothic horror, and it makes sense to stage it with imagery that readers will immediately connect to that genre. The big spooky house, the invalid, the corsets, the ghost — that creates a certain expectation of what the story will do, and then the ways that expectation is or isn’t met create a discourse. Having said that, it would be nice to write a book that takes place in 2020, because I would have to do a lot less research.

Carey: Speaking of Victorian and Gothic, there has long been a kind of aesthetic correlation drawn between the two eras. Do you think there is anything more to that connection, such as similar social mores or societal attitudes? Are there some underlying elements that seem to cause the two different epochs to coalesce and congeal into one sort of aesthetic whole, or should we just blame Alice Cooper for that?

Gfrörer: This question might be better addressed to a scholar of literary history, but to be brief: “Gothic fiction” is the name of a genre of romantic horror which was popular in roughly the Victorian era. It’s called that because some of the earliest works in the genre were set in the late medieval period, roughly when what we now know as Gothic architecture was in vogue (there’s no “Gothic era” per se, the word “Gothic” just means German). But the “Gothic” as conceived in the Victorian imagination is a very different thing from the reality of the people who lived in the late middle ages, and, likewise, our imagination of the Victorians is different from how they experienced themselves, a Victorian novel set in the middle ages is fundamentally different from a contemporary novel set in the time period, and so on. No matter what era we place our stories in, we never really write about any era but our own. As for what inspired the trend of medieval revivalism that began in the late 18th century, I really couldn’t say.

Carey: A recurring theme that I’ve noticed within your work is the marriage of the intimate and the frightening — not just on a “be careful what you wish for” level, but something far deeper: that we instinctively fear that which we desire most, and desire most that which we fear. Do you have any particular theories as to why that dichotomy seems almost central to the human condition?

Gfrörer: Not a theory, exactly — as a matter of fact desire and fear share a single brain circuit. In a sense they’re the same experience of arousal perceived in two different ways, and one can be mistaken for, or even enhance, the other — people feel sexual desire more readily after a fright, for example. Their symptoms are so alike (in psychology this phenomenon is called “misattribution of arousal”). I think involuntary responses are always exciting, the physical response to an emotional state — tears, trembling, sexual arousal — it’s thrilling to find your body, this cumbersome thing you’re responsible for, suddenly out of your control. It’s thrilling to make someone else feel that.

Carey: Along those lines, escape from everyday toil and drudgery into realms both fantastic and frightening are core conceits in both Black Is The Color and Vision. Is there a subtle message here about the true horrors of life being those that we subject ourselves to when we simply “go through the motions,” so to speak?

Gfrörer: You say “go through the motions” as if it’s a negative thing, and “we subject ourselves to” as if it were optional. Actually chores are value-neutral and mandatory. As long as life goes on, the bread must be baked, the animals tended, the children soothed, the fire fed, the clothes taken off and put back on again. It’s quite remarkable how little your despair matters when the rent is due. I suppose there’s something squalid in that, but then everything about being human must be squalid. The true horrors of life are frequently found in the domestic sphere, which is also where chores tend to be, but I don’t think that implies causation. Chores can be a solace, too.

Carey: What inspires you to make art? And by that, I don’t merely mean WHOSE work you take inspiration from, but what concepts, ideas, unresolved aspects of the human condition, etc. do you find compelling enough that you want to explore them?

Gfrörer: I’m interested in tragic love stories, obsessive sex, conflicted morals, betrayed trust, unreasonable demands, lies, self-harm, suicide. I can already tell this is an asshole answer, but I’m trying very hard to be honest. I like pain. I’ll chase anything that bleeds. The scene in “The Knight of the Cart” where Lancelot cuts his hand breaking open Guinevere’s window in the dark and unknowingly leaves her bed bloodstained — I could live on only that for the rest of my life.

Carey: Both Laid Waste and Vision revolve around characters who are tasked, voluntarily or otherwise, with being protectors or caregivers. Is there something about that role that you feel lends added pathos to your narratives?

Gfrörer: The books are based on my own experiences of being an involuntary (and largely inadequate) caregiver. It’s not symbolic. It’s just what they’re about. Black Is the Color is about that, too — Eulalia finds Warren on the brink of death and tries to help him. Maybe it’s less obvious there because she does such a terrible job.

Carey: And, finally — sex and death. What is it about the two that link them so inextricably in our minds? There is an element of danger in the intimate situations (physical and otherwise) you depict that reminds us of the connection between the two, and you do a masterful job of “upping the ante” with each as your narratives progress — in fact, it feels very much as though you may be channeling your own subconscious both through and within your art. Is the act of giving oneself over to a lover necessarily tied to the negation of the self, or is there a biological reality at play as well? That the act which leads to the creation of new life reminds us of our own mortality and that we’re, in a sense, tasked with creating those who will replace us? I’m guessing you may have some thoughts and feelings on the matter since you intertwine desire with at least the potential for destruction so frequently.

Gfrörer: I would hasten to point out that there is no procreative sex in any of my graphic novels (the theme of supernatural creatures stealing semen from mortal men for something akin to procreation appears in I believe two of my minicomics). It might not do to peer too closely in to the mystical association of sex and death — it’s not a puzzle I would want to solve. You know the joke, I think Žižek tells it in The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema, where the punchline is (imagine Žižek saying this, as Mary Magdelene) “I showed to Christ my pussy and he said, what a terrible wound, it should be healed!” And the moral of the story is that sometimes people enjoy their wounds. I’m sure vats of ink have been spilled about the relation of the sex drive to the death drive by people much cleverer than me, but if you see me running endlessly back and forth between the two it’s only because I enjoy them. I don’t really want to understand them. I would rather continue to lose myself in them.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply