As manga has been exponentially growing in popularity here in America, we’ve been fortunate to get many great collections of short stories by legendary artists from Japan’s comic-making history. In the last year or so, I’ve really enjoyed the new compilations from Drawn & Quarterly of Yoshiharu Tsuge and Kuniko Tsurita, as well as Viz’s recent reprint of Rumiko Takahashi’s Mermaid Saga. Around the same time, I discovered Glacier Bay, the new small press devoted to modern underground manga. In 2020 they released two volumes of the anthology series Glaeolia, which are full of exciting new work by current Japanese indy cartoonists. All of this has continued to lead me to a greater understanding of manga as a very broad art form. While I’ve had a nice time with these collections, I find that I have difficulty digesting the works.

Arriving at the end of a short story in a large anthology, I feel a need to move on to the next story. I forget to sit with and ruminate on what I read previously. Maybe this is some sort of ADHD thing, but I wonder if the story is done a disservice by this format. I’d much rather read these stories in the form of a mini-comic or graphic novella (I’ve even considered photocopying the stories into homemade zines for myself to read). The process of getting to the end of a story and closing a book gives me a nice finality to what I just went through and that can cause a great deal of reflection and catharsis. Besides, the activity of reading a small book object is a very pleasurable experience in general. I don’t have to struggle to hold a heavy tome open with my carpal tunnel-ravaged hands. In fact, I can read it with one hand while I sip my coffee.

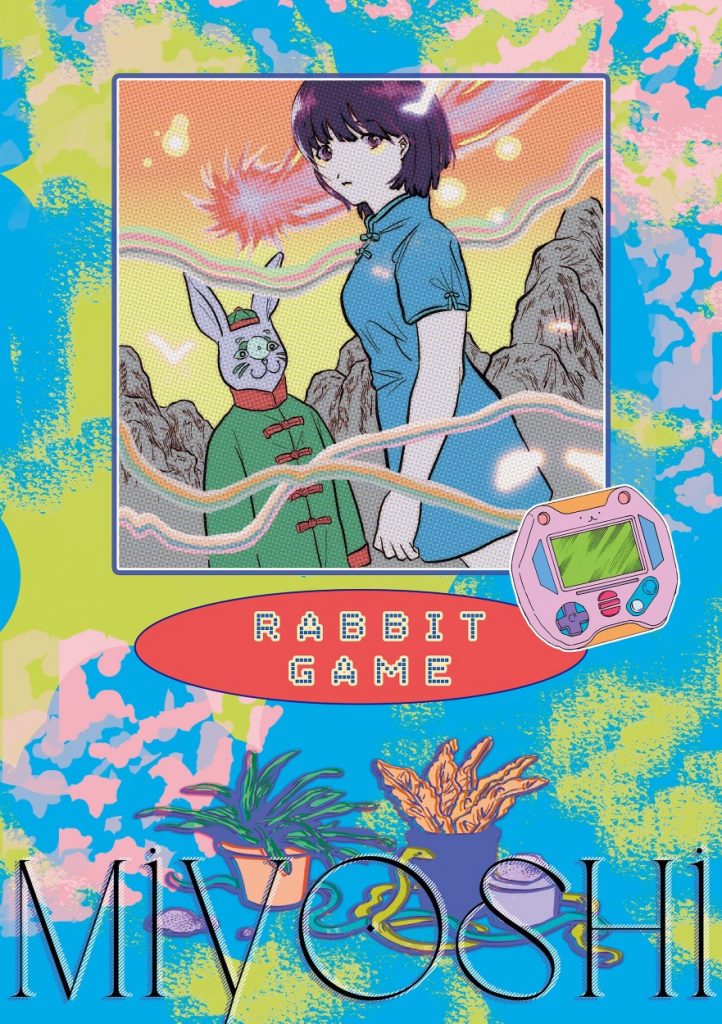

A particularly wonderful small book object is Rabbit Game by Miyoshi, published this year by Glacier Bay. It is a teen love and surreal horror comic that delivers everything with brutal efficiency. Right upfront you get a teenager, Inaba, bragging to her friend, Tooru, that she’s eaten a rabbit corpse. Inaba, as a character, is well-realized as someone who likes to act weird and say wild things to get reactions from her friends. For example, she tells Tooru that her grandmother was a machine and that she is a princess from the moon. This mysterious aloofness causes Tooru to become obsessed with her in the most awkward teen way possible. So they spend a lot of time together, and she gets him to buy a videogame called “Rabbit Game” that may or may not be cursed. Meanwhile, Tooru keeps hearing rumors that Inaba is actually dating their childhood friend Kawamoto (who has, incidentally, joined a cult.) Again, this leads to some extremely well-represented youth-in-love angst. Eventually, Tooru starts to fantasize about Inaba while playing Rabbit Game and begins dreaming about getting sucked into the game’s universe with his friends. The story gradually transitions into very spooky “is this a dream or am I awake” sequences which lead to a finale that doesn’t offer any concrete answers, for which I was very appreciative.

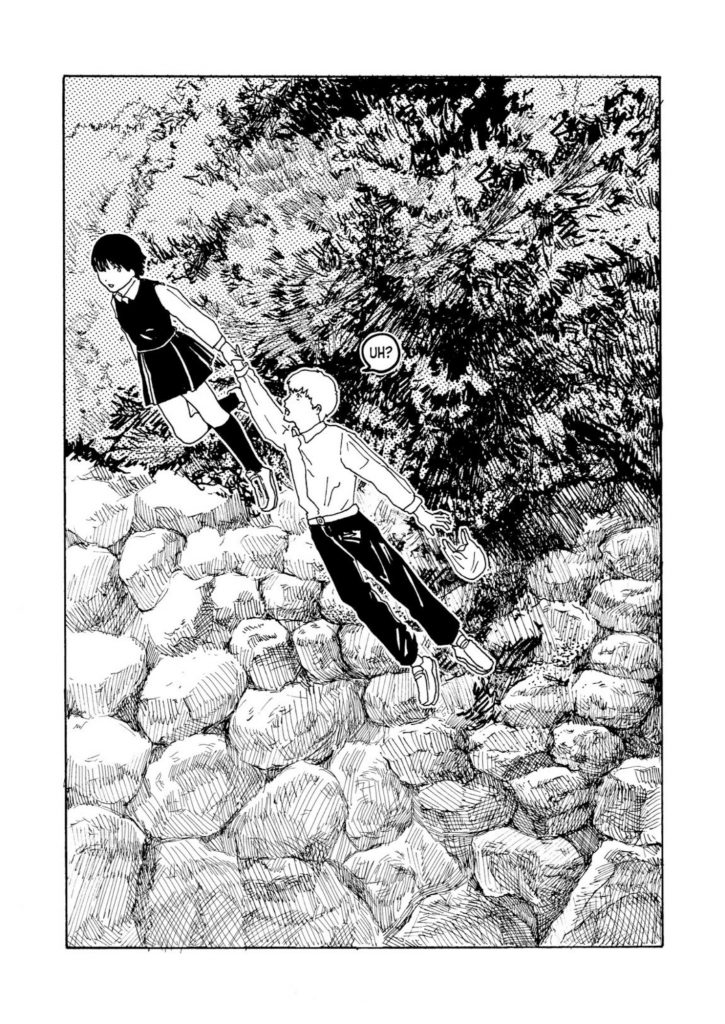

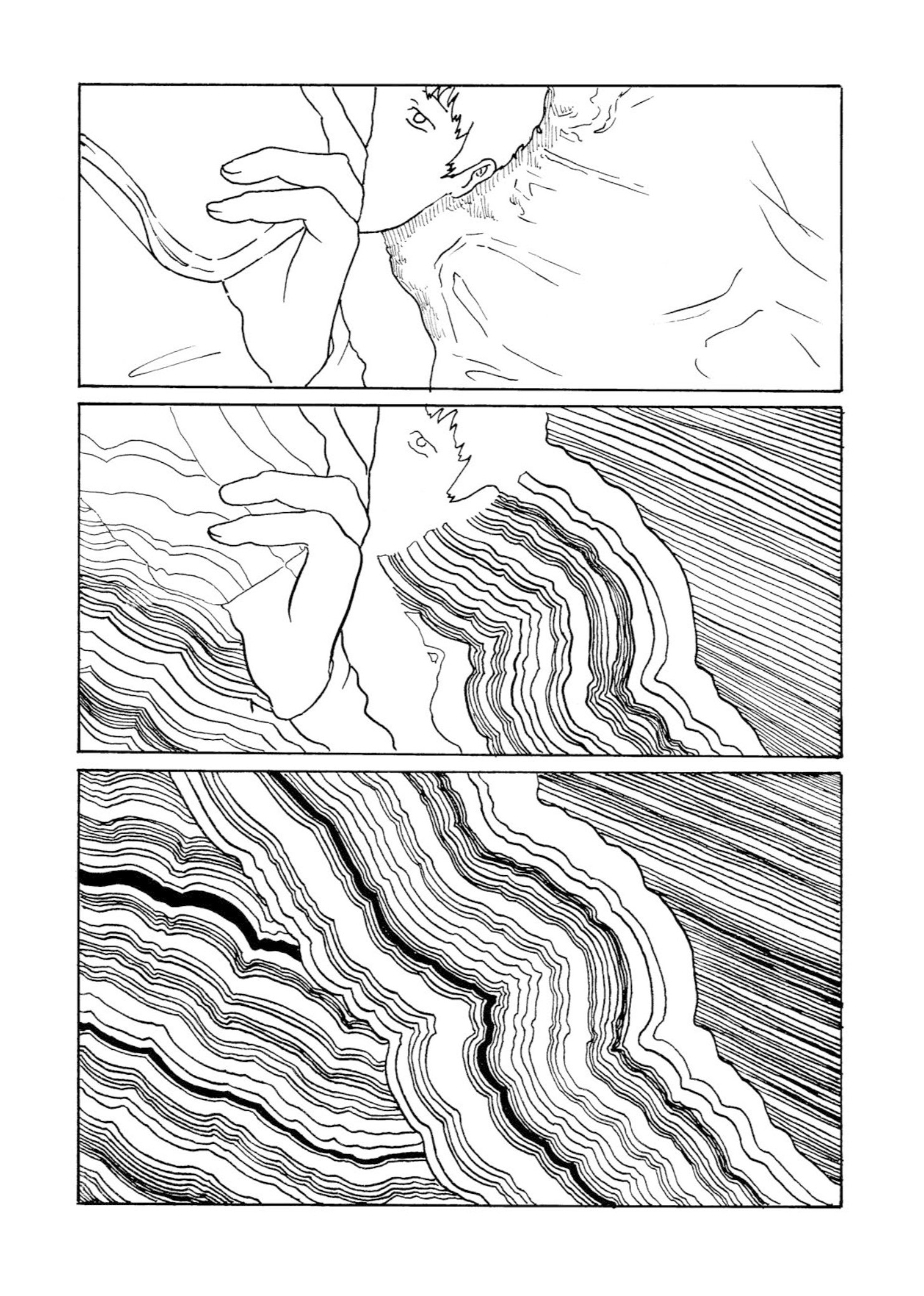

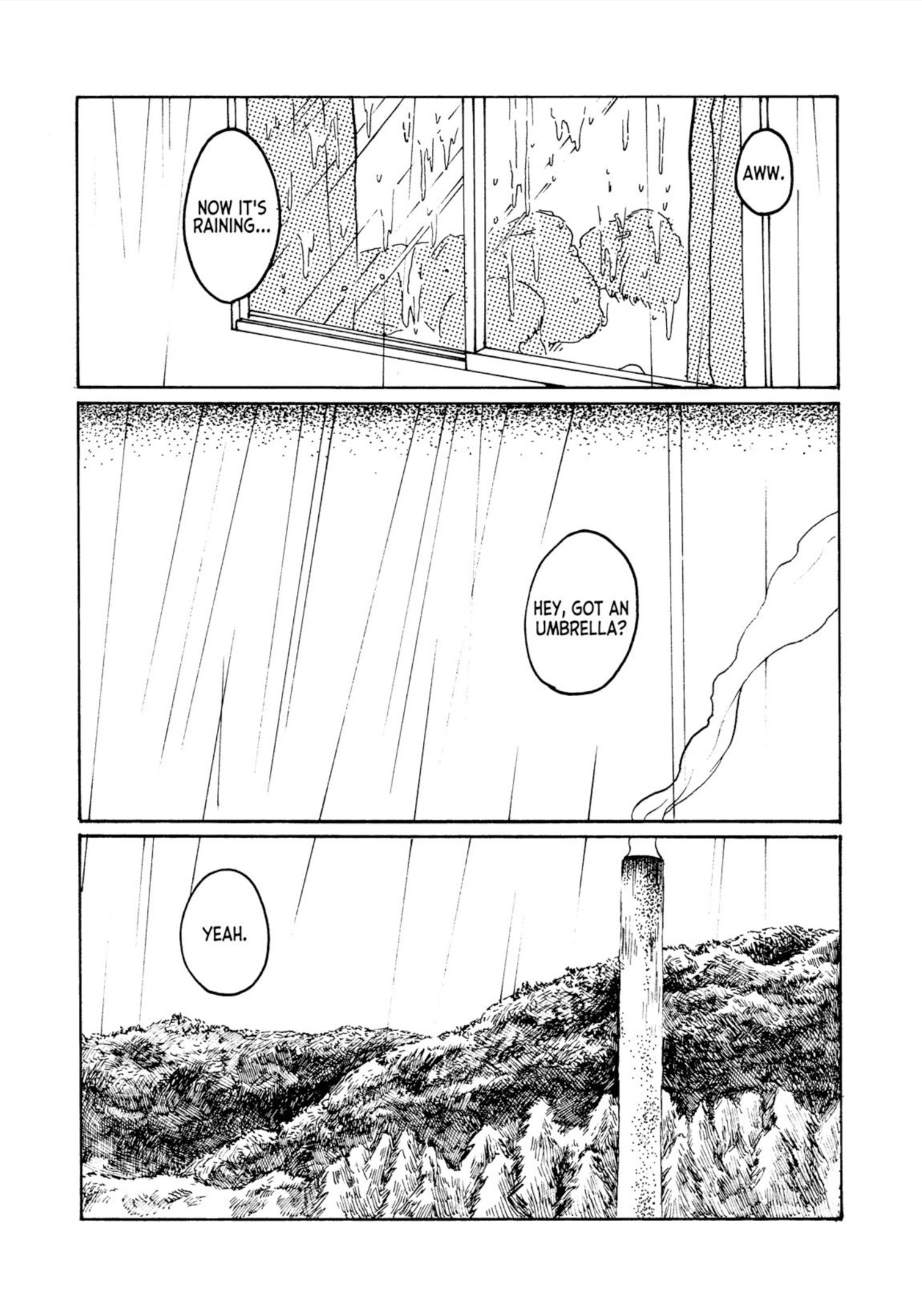

What makes Rabbit Game so effective and the reason I love it so much is that Miyoshi and book designer Emuh Ruh use every aspect of the comic book format in a way that creates atmosphere and draws a reader into the story: everything from the wild cover design that immediately makes me go “what the heck is this!?”, to the use of a zip-a-tone effect which creates an eerie, shadowy quality on each page. Miyoshi uses layout and page turns to devastating effect. There are so many moments where I turned the page and gasped because of the beauty and scope of what was revealed. One ingenious scene transition moves from Tooru looking out a window at the rain to the rain traveling down the page to reveal the next location. Later there’s a double-page spread that completely knocks my socks off, wherein Inaba finally takes Tooru’s hand and they start flying. It’s all in his head but it perfectly captures that very specific feeling of being a teen in love.

There’s a lot going on in this short manga. Food horror, teen love, loss and trauma, cultists, dream logic, and perhaps some commentary about kids getting too sucked into video games, all the while delivering a consistent and viscerally unnerving atmosphere. Early on, a jelly roll is compared to the insides of the rabbit that Inaba ate. Characters’ faces are often obscured or cut off halfway, and panels are often focused in a way that keeps characters cut off in an unsettling way. As the story turns more into surreal horror, the layouts and transitions get appropriately “out there.” Characters get pulled away from reality by the video game and their bodies bleed out into thick lines of static as they transition to the fantasy world (this same static imagery is used on the inside covers which is another one of those design decisions that I really appreciated).

It’s hard to talk about the second half of the book without spoiling the story, but one of the most intense sequences is a completely upsetting bit where Inaba opens a food platter and a dead, naked Inaba is revealed as the meal. She’s standing next to Tooru and offers him a knife. “You wanted to do this with me, am I wrong?” She says. Tooru: “No… That isn’t what I meant.” Inaba: “This is what it means. This is no different from what you want.”

I love this book. I love how it tells its story, the way it’s drawn, and the way it is put together. My only complaint is the slightly rubbery texture on the cover, but that seems to be what everyone is using these days, so I’m sure there’s a good reason for it. Other than that nitpick, Rabbit Game is an incredibly satisfying manga to spend a quiet moment with, and, to me, there’s almost nothing better.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply