They say that as you get older time moves more quickly. If this last decade is any indication, I should be in my 90s by tomorrow. The last ten years for me have been full of both major upheavals and quiet consistencies. The one through line in it all, though, has been comics. I started my site, Your Chicken Enemy, at the tail end of 2010, and through all of its permutations, it always had comics at its heart. Now, here, at SOLRAD, I get to take this focus, this love, to the next level.

I’ve always been leary of the concept of “Best” for a number of reasons. The first is the hypocritical subjectivity of the concept that the term inherently denies. Next is the fact that there is far too much content for any entity to have consumed in its entirety. So at YCE, we tried not to use the term “best”. Rather, embracing the celebratory nature of these sorts of lists, we called them “Books We Liked”. I’d like to continue that idea at SOLRAD. And that’s what this list is: Books I Liked in the last decade, the ones that stood out in my remembrance, the ones that linger still through the passage of time.

(The following are presented in alphabetical order by the creator’s last name)

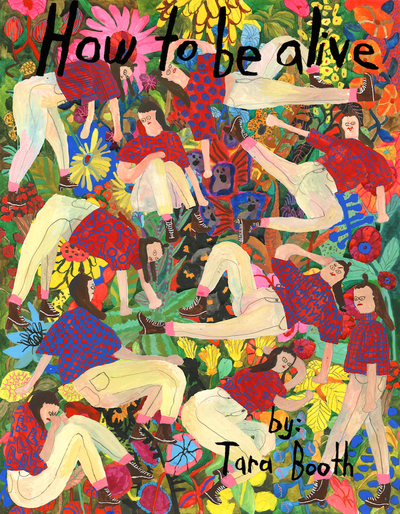

How to be Alive by Tara Booth (Retrofit/Big Planet Comics, 2017) – Collecting 40 of Tara Booth’s wordless, one-page, colorful and patterned gouache paintings, How To Be Alive reads like a secret spy camera recording a woman, perhaps Booth herself, in her car, her space, her world. She’s going through all the motions of living a life trying to come to terms with the small failures and equally small triumphs that comprise her day-to-day. From changing clothes to cutting hair, from gobbling prescriptions and wine and food, to finding matching socks, or just trying to get comfortable, these are the tiny dramas that engulf our days and ensure our perpetual discontentment with all the things that defeat us, even as we strive to be our best in a world that ultimately registers our existence only slightly. How To Be Alive is humanity in all its petty rawness.

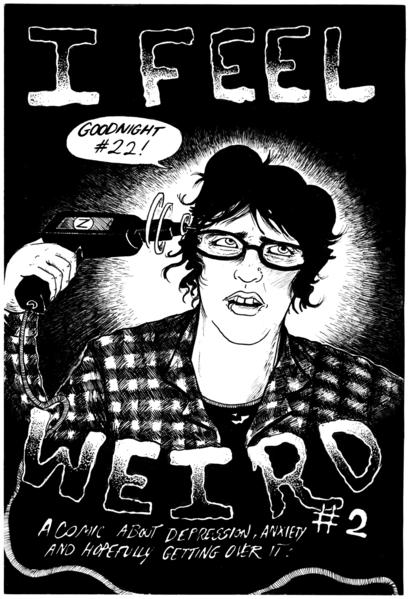

I Feel Weird by Haleigh Buck (Atomic Books, 2016-present) – Raw, confessional, naked, powerful, oftentimes funny, poignant, and full of truth, Haleigh Buck’s I Feel Weird series maneuvers through her own understanding of herself in her world and, in doing so, ends up touching upon the universal. Her thick-inked pages reflect the smudges and obfuscation we shroud ourselves in on our bad days. Her cartooning is damp with the desperate sweat stench that pervades our bedsheets during dark days when our depression won’t let us leave our rooms. Her panels and lettering are jagged with the electricity of anxiety and the charge of panic attacks. This is a visceral and ultimately healing series of comics. I Feel Weird reminds us that no matter what our asshole brains tell us, we are capable of spectacular things, things that will remain undone until we do them, and that we are the only ones who can make them a reality.

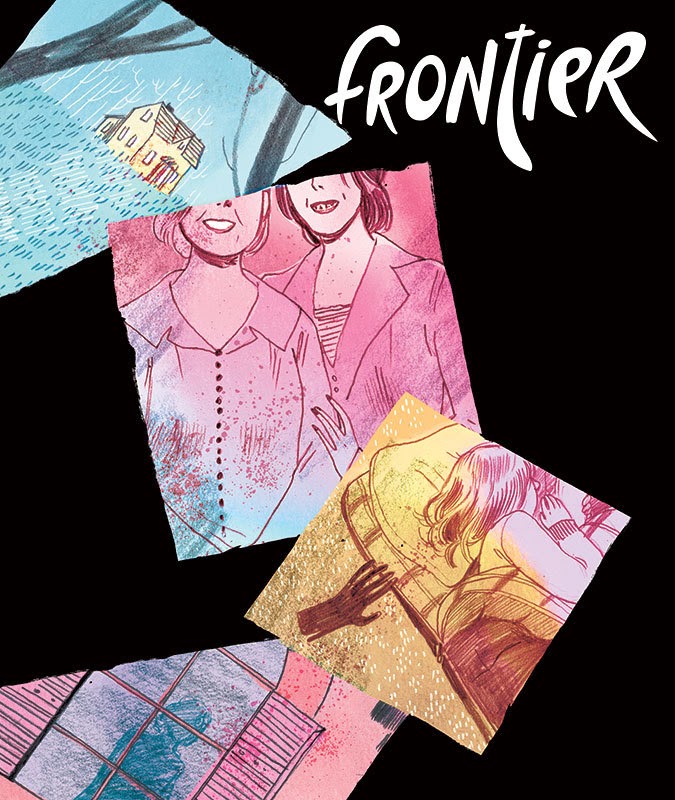

Frontier #6 (Ann by the Bed) by Emily Carroll (Youth in Decline, 2014) – In Ann by the Bed, Emily Carroll attacks the conventional narrative with a surgeon’s scalpel, cutting through cause and effect. She moves her reader through time and space, disconcerting as she disconnects, adding a layer of displacement to her tone. Her apt choices of art style and color use each add another emotional hue. She also varies the thickness of her inking to contract and expand, and her lettering changes to resonate with the mood. In Ann by the Bed, Carroll uses all the evocative tools that comics offer in order to create an amazing reading experience. It’s also one of the scariest comics you’ll read.

Nod Away by Josh Cotter (Fantagraphics, 2016) – Nod Away is the first of what Josh Cotter promises to be a seven-volume series. Ostensibly this first volume is a sci-fi story that circles around issues such as the human desire for exploration and connection, the power structure inherent in gender politics, and the gray area created in the intersection between science and morality. As the book unfolds, though, the reader feels there is something more complicated occurring in the periphery. Cotter is exploring profound questions about consciousness itself. Densely detailed and tightly packed, Cotter’s pages pull and push the classic nine-panel grid layout as the emotional beat demands. His layouts control the reader’s experience explicitly and play with expectations in order to keep things just off-balance enough to demand an active reading.

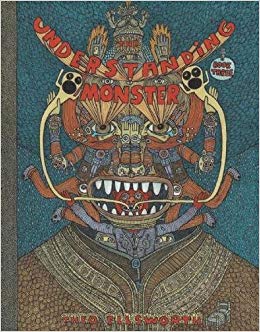

The Understanding Monster by Theo Ellsworth (Secret Acres, 2012-2015) – The Understanding Monster series by Theo Ellsworth demonstrates his trust in his audience. Ellsworth expects that, regardless of how alien the words and images appear in his books, the reader has the capacity to understand. Structured logic comes apart quickly in Ellsworth’s work, and it’s not fully replaced with a primal or visceral understanding either. Rather, The Understanding Monster demands a different way of interacting with the material. It requires faith and here, that faith is rewarded.

Dog Nurse by Margot Ferrick (Perfectly Acceptable Press, 2018) – Inscrutable, triumphant, and beautiful, Margot Ferrick’s Dog Nurse seems incredibly personal, yet it unfolds as if she is forcing a distance between herself and her art. In addressing issues like communication, compassion, self-efficacy, parenting, abuse, and innocence, there is sadness and hope at the core of Dog Nurse. Ferrick seems to be both exploring trauma and celebrating the discovery of one’s voice. She presents a dream-like meditation that verges on the revelatory. Pushing away direct identification, Dog Nurse operates on the periphery. The reader looks into a mirror when reading this comic but is unsure that the reflected image is really how they want to be seen.

Greenhouse by Debbie Fong (self-published, 2018) – Everything in Debbie Fong’s Greenhouse works in tandem to define both tone and theme. It’s an important meditation that reminds the reader of the importance of connection and of the need to be seen. Greenhouse speaks to the paramountcy of mattering to someone other than ourselves. It posits the truth that we grow best in the open among other flourishing things, not shut in, regulated, and alone.

Our Mother by Luke Howard (Retrofit/Big Planet Comics, 2016) – Luke Howard’s Our Mother is an exploration of the effects of anxiety disorder. It works in a structure that seems dispassionate, yet ends up poignant and powerful, getting to the truth behind trying to comprehend that which is incomprehensible. It reminds us that sometimes we become who we are because of what has happened to us, not through what we have chosen to occur. Our Mother is a book that demands an almost instant re-read. And then probably another reading after that.

Plans We Made by Simon Moreton (Uncivilized Books, 2015) – Simon Moreton takes apart the rawness of yearning in Plans We Made through narrative, through pace, but mostly through his simple lines and layouts. In Morton’s pages, forms are dissolved into naked shapes through which the reader makes meaning, attempts closure, and overlays the self. Here, what is less becomes more; each moment is about that which is unsaid and undrawn. Plans We Made is a quiet book. Yet, in Moreton’s hands, it has so much important things to say.

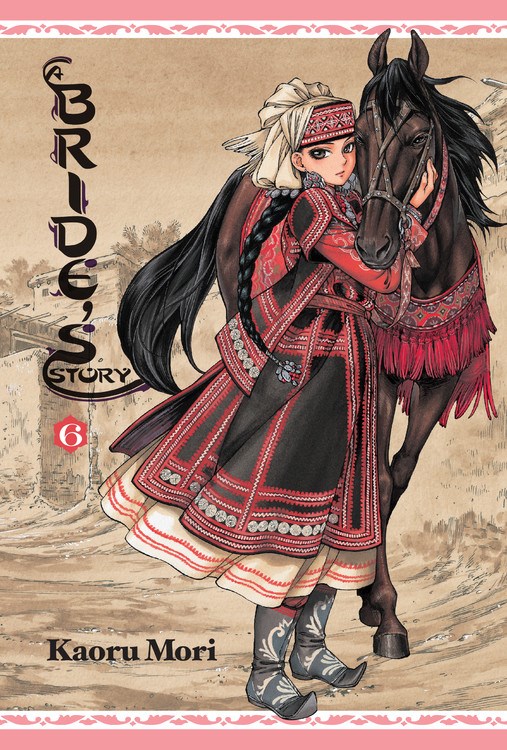

A Bride’s Story by Kaoru Mori (Yen Press, 2011-present) – I’ll admit that I haven’t read much manga, but when Alex Hoffman insists that you read THIS manga, you go to the library and check it out. Damn, am I glad I did. The 11 volumes of A Bride’s Story are a feast for the eyes and sustenance for the soul. The late 19th century story, for the most part, is focused on the budding relationship between a 20-year-old woman from a Central Asian semi-nomadic tribe and her 12-year-old husband. But this story is really a background for extensive character development, a rich examination of the various cultures of the area, an exploration of the relationship between humans and their environment, thick musings on art and science, and, hands down, some of the most kinetic, detailed, and beautiful cartooning I’ve ever seen. This is a series focused on the agency of women, the imprisoning aspects of cultural norms, and the importance of community. A Bride’s Story is thoroughly engaging on all levels.

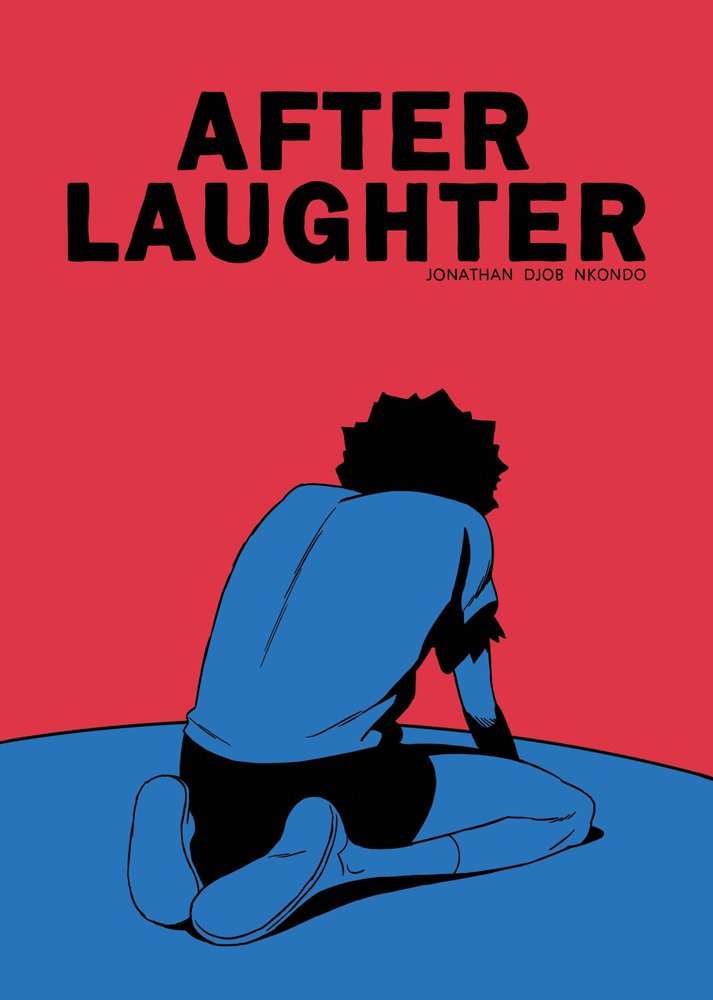

After Laughter by Jonathan Djob Nkondo (ShortBox, 2017) – After Laughter by Jonathan Djob Nkondo is, perhaps, a perfect comic. This wordless 44-page, black and white book reads as if it were a short film. It reflects movement and time, focusing attention and perspective in a manner rarely found in comics. Nkondo’s clever use of negative and positive space adds to what he is seeking to convey. Here, new truths are created. Here, new understandings arise. Here is a damn good comic.

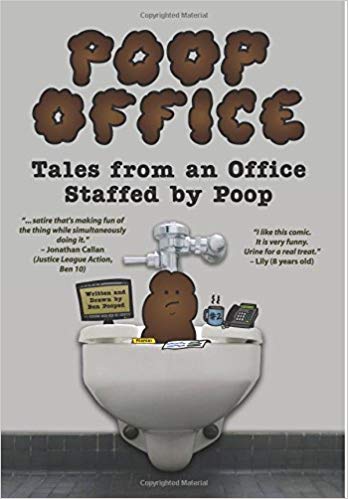

Poop Office by Ben Pooped (self-published, 2017) – Say what you will about Ben Pooped’s collection of gag comics featuring an office staffed by turds, this is Swiftian satire on an obtuse level. After reading it, it is almost impossible to operate in any corporate structure without breaking into a hollow existential panic. Crudely drawn, crudely executed, and just plain crude, it is political polemic and cultural diatribe — it points its shitty finger directly at your soul.

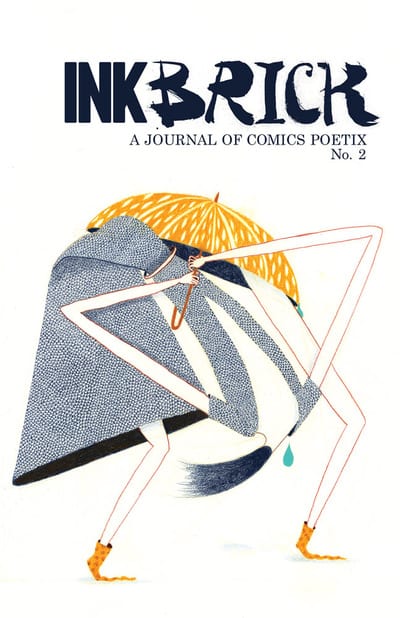

Ink Brick edited by Alexander Rothman, Paul K. Tunis, Alexey Sokolin, Matthea Harvey (various publishers , 2013-2019) – Nobody has done a better job of explaining, curating, and championing comics poetry than Alexander Rothman and Paul K. Tunis and their Ink Brick anthology. Since 2014, they’ve put out 10 volumes, publishing over 800 pages of original comics poetry by more than 100 creators. Comics poetry addresses the conversation between the parts of the brain that make both logical and emotional sense of the world. The typical way of reading must be reassessed for a moment in the face of comics poetry. To fully engage with it, the reader must lower his or her defenses and allow for chaos to supersede meaning for just a moment. It asks you to get uncomfortable, and then get quiet. Ink Brick provides the perfect space for this interaction, and it has done more for the genre than any other publication out there.

Tintering by Conor Stechschulte (self-published, 2017) – Its title taken from a quote from Agnes Martin (“Artwork has only a tintering of what it attempts to represent to the artist or responsive observers”), Conor Stechschulte’s Tintering examines the relationship between an artist and their art, and the obligations of observers of that art in perpetuity. It tells the story of five outsider artists who created public pieces to reflect their own particular vision, all of which were subsequently destroyed. Stechschulte does this through the means of broken objects, highlighting the transience of all things. As if an eternal recurrence, each story follows a similar pattern, yet is sprung from a unique moment of inspiration. I really love this book.

Eye of the Majestic Creature by Leslie Stein (Fantagraphics, 2011) – Leslie Stein’s Eye of the Majestic Creature series collects the story of Stein’s semi-autobiographical and wildly wonderful alter-ego, Larrybear. Her comics are open, colorful, funny, poignant, and beautiful to look at. Stein is a voice for a certain aspect of her generation, the ones you see feigning ironic detachment while inside they are either all honest excitement or vast empathy. While it’s just so much easier and cooler not to get emotionally involved, for people like Stein, that’s just not possible. Eye of the Majestic Creature captures this perfectly.

Frontier #7 (Sex Coven) by Jillian Tamaki (Youth in Decline, 2015) – When you do the work to have an emotional response to art, you are the owner of that experience. Authentic emotions are precious in a world where we are so often sold how to think about things, where outrage is manufactured, enjoyment is a science, and attention an algorithm. Nobody latches on to this preciousness more than young people, especially when their peer group embraces something, especially when they see that their parents don’t understand it, even more so when their parents fear it or hate it. Jillian Tamaki captures all of this in Sex Coven. The intensity of the reaction to music and the rituals it inspires are all laid out in this comic with fervor and excitement. Tamaki knows the proper moment to abstract her art to convey this, and when to focus on minutiae in order to set context and further her story.

What is Left by Rosemary Valero-O’Connell (ShortBox, 2017) – There is a certain softness in periwinkle and pink. They are almost non-committal colors, neither this nor that, calling forth malleability and tenderness. It’s the moment right before dawn. The cheeks of a newborn. All that possibility — fecund with that which comes next. Such is the palette from which Rosemary Valero-O’Connell paints her 36-page comic from ShortBox, What is Left, giving it an emotional tone that would otherwise elude her narrative. It is this choice that gives this space-wreckage story its core. These colors saturate Valero-O’Connell’s undulating, tentacled, and sinuous lines, adding movement and grace. What is Left transforms tragedy to beauty, and, by doing so, gives it a fundamental humanity.

Eel Mansions by Derek Van Gieson (Uncivilized Books, 2015) – Derek Van Gieson is a culture vampire, suckling at the teet of what passes for popular entertainment, and, in the bowels of his work, transforms it into a viscous plasma of a new reality. Eel Mansions is the blood that pumps through the heart of a society blissfully sedated by its constant need to be passively distracted. Horrific, humorous, and holy, nothing is like Eel Mansions.

A City Inside by Tillie Walden (Avery Hill Publishing, 2016) – Tillie Walden’s A City Inside is a book of hope, but one that does not mollify the complexities of life: its isolation and its din, the damage of the past and the uncertainty of the future. There is empathy and kindness here, as if Walden is as much an open heart as she is a powerful artist. All of the heavy intricacies of her lines in this book and the thick blackness that subsumes so much of the environments of her pages all point to a simple understanding and a lightness of communication. It is as if what Tillie Walden exhales here allows the rest of us to breathe.

Prince of Cats by Ron Wimberly (Vertigo, 2012)

In Prince of Cats, Ron Wimberly has full control of his craft: from the cartooning to the colors to the writing to the layout – it is complete in every aspect. It dares to tell the story of Tybalt from Romeo and Juliet, transported to Brooklyn in the mid-80’s, now made hip-hop and ninja, pierced and cocksure. By taking on this dare, Wimberly breathes new life into a tragedy that has been watered down through endless reimaginings and interpretations. He transforms it and creates a new tragic hero, one that is believable, one that is true, one that is flawed by hubris and empathy at the same time.

Extra Special Mention:

Casanova by writer Matt Fraction and artists Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon (various publishers, 2007-2017) – All comics might want to consider, at some point, becoming this damn fuckity.

Leave a Reply