Leslie Stein’s memoir comics have always had a deeply existential quality. Her latest, I Know You Rider, continues to explore the relationship between seeking out sublime moments as a way of not only feeling happiness but also establishing meaning in her life. However, this book not only sees Stein exploring aesthetics and ontology but also ethics and epistemology as well. She takes a deep dive into not just what makes her happy but also considers a number of alternate paths she might have taken by spending time with her friends. That biggest dive into another life comes when she learns she is pregnant and decides to have an abortion. While that’s the framework the book revolves around, the other events in the book are no less significant in her meditations on what she really wants out of life.

There’s always been a deep relationship between form and content in Stein’s work. In her quasi-autobiographical series Eye Of The Majestic Creature (collected in two volumes by Fantagraphics), she worked in black & white using a combination of whimsically minimalist but rubbery lines for character design and a dense stippling technique that gave her drawings weight and power. All of this was in service to a magical realist depiction of her life where her stand-in character Larrybear often engaged in conversations with her best friend, a guitar named Marshy. Most of these comics focus directly on the primary tension in Stein’s work: a deep, abiding sense of introversion bordering on solipsism and an aching need for connection. The visual whimsy of the absurdist elements was balanced against the darker themes she explored, all contained in a tight grid.

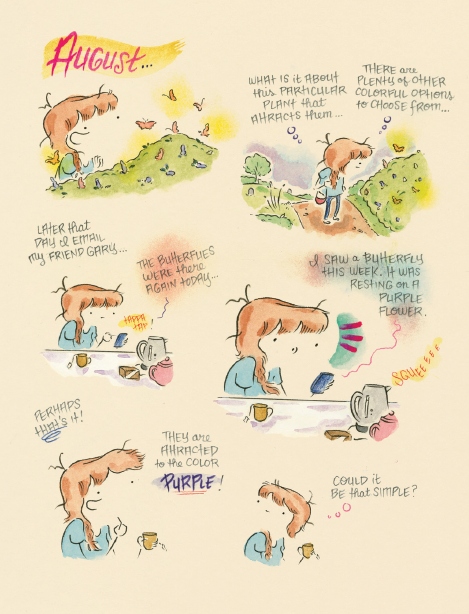

Stein has noted that she moved in a different visual direction as a result of one of her many formal experiments. Starting with Bright-Eyed At Midnight and then its subsequent follow-up Present, Stein has used an open-page layout with a watercolor approach that almost entirely subsumes line. Stein was a minimalist before with regard to character design, but her own self-caricature is dominated by the auburn of her hair and her colorful outfits. Her own face is just two dots for eyes and variations on a tiny curve for a smile, and that’s it. No chin, no cheeks, no nose, and she frequently doesn’t even bother using a line to fill in the shape of her head. She leaves it all to negative space and the reader to fill in, allowing them instead to focus on her vibrant and cheerful use of color. She is still a humorist at heart, keeping the tone light throughout with regard to most of her interactions. At the same time, the gag she thinks of while working, “Yelp For Babies,” is an interesting presage for the rest of the book.

In an interview with The Paris Review, Stein said regarding her decision to use color that “I was working nights at the bar and so wasn’t seeing daylight at the time. I brought light and color into my life through the drawings.” There were other formal changes that went along with this decision that were directly related to accessibility and sharing her work with the public. Eye Of The Majestic Creature was originally a minicomics series. It was a loose narrative that went in some unusual directions, but it was still self-contained in this magical-realist world. Stein’s first color experiments popped up on Tumblr and were eventually serialized in Vice. As a result, she started writing shorter vignettes that were later collected with a loose theme.

I Know You Rider started as a cryptic Instagram post regarding her abortion but turned into her most cohesive personal narrative. The opening scene, set prior to the title page, is simply Stein wandering around a “bucolic cemetery” in Brooklyn. Here, Stein delights in being outside and luxuriating in the sublime beauty of nature, which she conveys through her use of color. The very first image we see is a staggeringly beautiful drawing of the outside of the cemetery, meshing the looseness of her line with colors that accentuate its most outstanding features. The image is the only one on the first page, as Stein is walking up to the building, and it’s meant to convey a sense of awe. It’s awe not just at the structure itself but at the beauty she sees in it and its gardens.

In Kantian terms, this is the experience of the sublime. It is grounded in a particular time and space, but the description of this feeling we experience is our understanding of what he would call the ideal world. For Kant, this is a reflection of God, an experience that we can try to describe and turn into a narrative, but it is important to understand that the narrative is not the experience. We can talk about it and around it, but never quite get at “it”. This brief sequence is a recapitulation of Stein’s personal experience with the sublime and how it functions as the foundation of why she’s an artist. In trying to convey her experience of the sublime, she herself creates sublime images.

This is important information and it pops up again throughout the book, but Stein covers a lot of different ground here. After this brief vignette and the title page, the next vignette sees her in an abortion clinic a few months later. Stein goes back and forth in time throughout the book, telling a little of that particular story at a time that provides the meat of the plot. Along the way, she talks about her relationship with the man with whom she got pregnant, her thoughts on children and having children, and a variety of other encounters with friends and relatives. If her other books are about that tension between loneliness and needing to be alone, this narrative shows someone who’s come to terms with that tension and allowing herself to find fulfillment in both states.

What Stein grapples with instead are the fundamental questions of philosophy. The fundamental question of aesthetics, “What is beauty and why is it important?”, is covered by her other work and summarized in that first vignette. However, she asks the fundamental questions of ontology (“What is being?”), epistemology (“What can we know?”), and ethics (“What should we do about others?”) as well. Along the way, she takes on another dilemma: What does it mean to live a life with meaning vs a life where we seek happiness?

In Stein’s understanding, all of these questions are related. Providing a framework to connect them all has been the primary project of philosophy for thousands of years, from Aristotle’s work on virtue to Kant’s creation of rules-based, deontological ethics to Mill’s utilitarianism. What we can know affects how we can act. There’s a running gag in the book, which treats these difficult questions with light-hearted humor, where Stein starts reading different philosophers but is put off of them because they are problematic. She tells a friend of hers with a philosophy degree that she was going to read Heidegger, the man who invented existentialism, until she learned he was a Nazi. So he recommends Nietzsche instead (“All artists love Nietzsche”), and she starts reading The Birth Of Tragedy until someone on a plane says that he’s problematic because he focused on the racist German composer Wagner. So he recommends Descartes instead, ie, the “I think therefore I am” guy.

What’s funny about this progression is that all three philosophers were well known for taking a wrecking ball to the history of philosophy with their works. Descartes revolutionized epistemology with that statement, with the self-evident proof that the only thing I know is that I am thinking these thoughts. All other knowledge stems from that first revelation. Heidegger rejected that, believing that all thought and language was self-delusional because it denied the one important thing about ontology: we are all going to become non-existent, and we do everything we can to deny that fact. Nietzsche destroyed the Kantian system of ethics based on knowledge as anti-humanist on its face and offered no solution other than a total withdrawal from society.

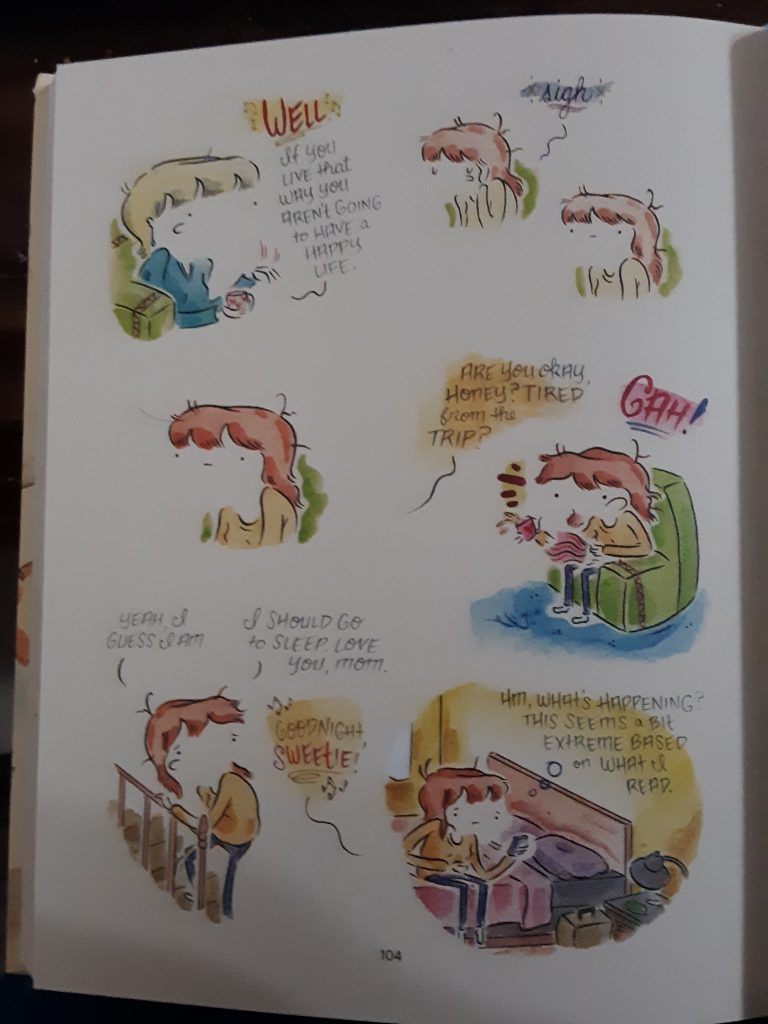

Notably, none of these three men had any interest in ethics. How should we treat others, and why? However, as the other foundational aspects of philosophy nagged at Stein, it was this question of ethics that was most important to her. There’s a discussion she has with her mom where she asks her about the moral implications of bringing children into the world. She asks the theoretical question “What if you were opposed to the very idea of having children even though you wanted them?” Her mom replies, “So you’d be living based on your ideals? Well, if you live that way, you aren’t going to have a happy life.” That is a deft summary of what it means to be virtuous vs what it means to be happy, a distinction that Stein eventually recontextualizes later.

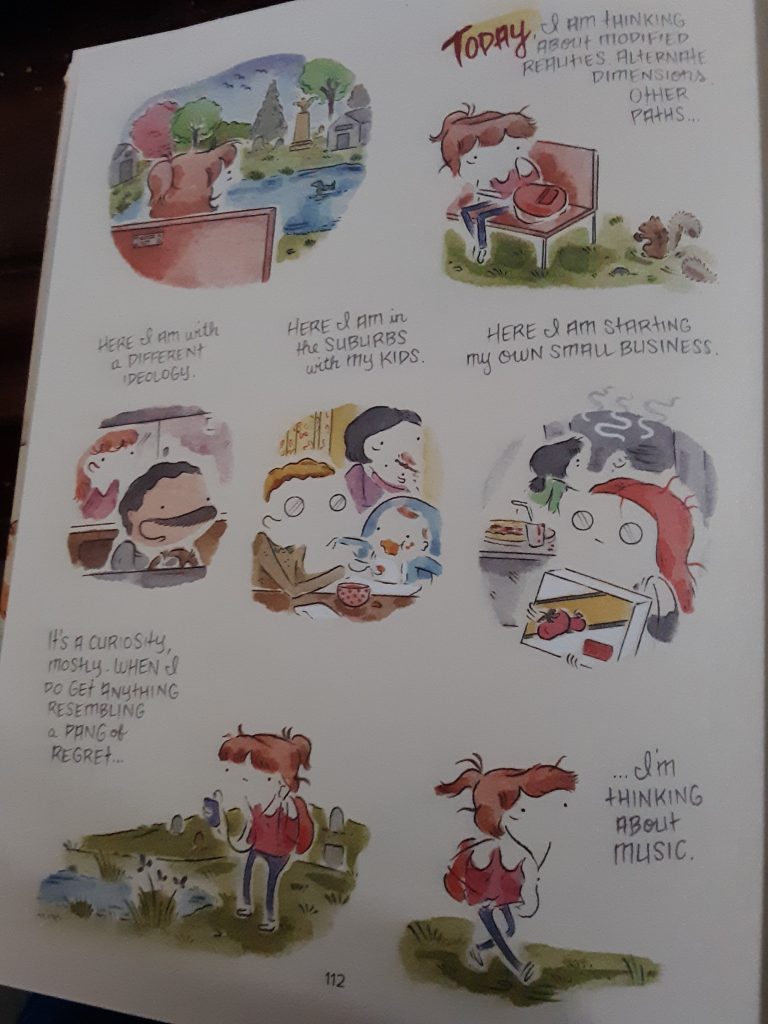

There are several visits in the book that she has with friends that are meaningful in their own right, but also serve the larger context of being looks into alternate universes. There’s a life where she could be living in the suburbs with twins and a husband, like a friend she visits. There’s a life where she’s starting a small business like her friend with a pizza parlor, one who decides that having children is immoral. There’s a life where her entire philosophy of life is different, like a taxi driver with six children. There’s a life where she decided to have that baby. For Stein, these encounters and her genuine interactions with others provide epistemological and ontological clues for her own life.

What do we do about others? At the very least, we can imagine trying to live their lives, thinking about the decisions they must make and why they make them, and doing this without judgment. There is a deep sense of acceptance in this book that goes along with a fundamental understanding that rigidity of thought leads to unhappiness. She allows herself to mourn the experience of her abortion and simply accept the feelings that she has, which allows her to eventually move on. The man who got her pregnant and said that he didn’t believe in relationships eventually became her boyfriend, displaying his own ability to expand and evolve when circumstances changed.

There’s another author that Stein doesn’t mention in this book whose work is pertinent, and that’s Jean-Paul Sartre. In particular, Nausea stands as perhaps the finest distillation of both what it means to use the tool of phenomenology to understand the world and how it plays into destroying the core of every belief system and idea about happiness as part of existentialism. Sex, religion, politics, relationships, etc. alone all lose their sense of meaning for the protagonist. The only thing that provides a hint of happiness at the end, and this is something Heidegger hints at as well in his work, is music. Stein is a guitarist who used to be in the band Prince Rupert’s Drops, and some of the last sequences in the book follow her on a snowy night where she makes a connection with two different bands in completely different genres. She admits that of all the “lost universes” she had pondered, the only one that truly gave her any sense of regret was not playing anymore. It was a coincidence that she was out that night and made these connections, and the idea of coincidence vs fate is another running theme in the book. One musician she makes a connection with says that there are no coincidences, while her philosopher friend says that pretty much everything is a coincidence.

What Stein comes to understand is that it doesn’t matter; the important thing is that she has managed to link her passion for art in the form of music with collaboration. It’s an act that inherently recognizes the value in another person, that acknowledges that you see them and they see you. It creates and rewards empathy. These are the fundamental aspects of humanism, and Stein understands that aesthetics can create this bridge between existentialism and ethics.

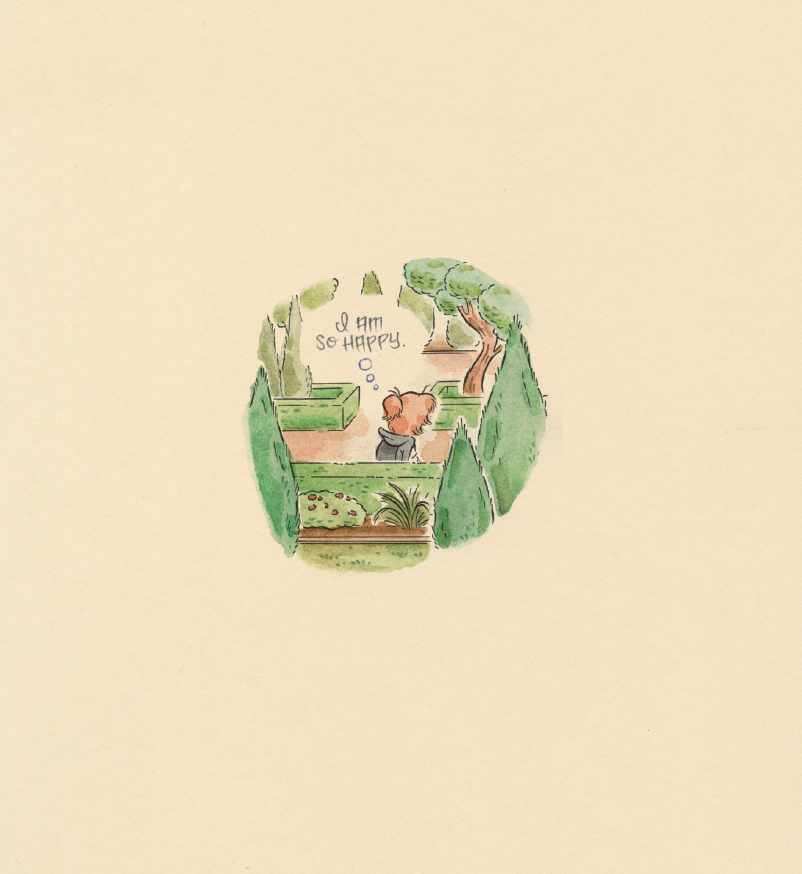

The final scenes in the book are a callback to the first, as she and her boyfriend visit the gardens at the Alhambra in Spain. He casually tells her that he loves her and she tells him that she loves him too, as she reaffirms how much she loves being outside, surrounded by beauty. The last image we see of her is where she says, “I am so happy,” much as she did earlier in the book where she was walking around a different set of gardens. What’s different here is the shared aesthetic experience they have together. The final image of the book is another breathtaking drawing of a structure surrounded by trees, brought to life through her vibrant use of color. It’s an affirmation of her journey as an artist and a person and an understanding that pursuing beauty isn’t simply restricted to appreciating what we see; it can be cultivated through our relationships as well.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply