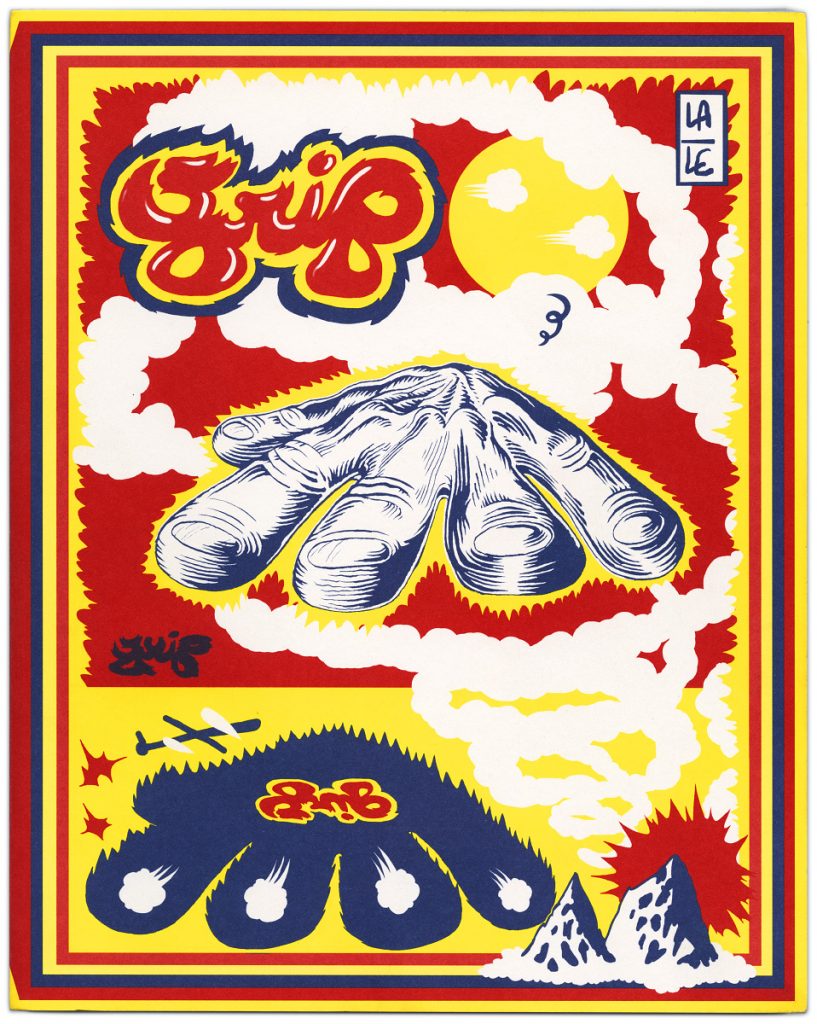

Wonder and awe permeate the experience of reading Lale Westvind’s Grip. Better yet, it manages these states while also rejecting the juvenile and fascistic elements of [male] adolescent power fantasies found in mainstream superhero comics, mine and many’s entry point into comics. Grip provides a distinctly feminist power fantasy that centers its main character’s development of her superhuman abilities as a craft utilized towards greater autonomy, inner peace, and collaboration. In doing so, Westvind celebrates the lives of craftspeople and blue-collar workers, showing the vitality of the lives devoted to making and serving, and the opportunities fostered through access to that embodied knowledge.

While the structure of Grip initially mirrors superhero origin stories, Westvind’s tale quickly departs from it following the character’s encounter in an alley with a force, represented as a gust of air, that imbues her with the ability to manipulate any matter she touches. After first struggling to understand and accept her new power, the nameless hero encounters a mentor, introduced to her by the protagonist’s maternal figure, that possesses a mastery of similar abilities. Then the mentor leaves, never to be seen again, the first in a series of women that support this new stage of life, and demonstrate a horizontal tutelage disinterested in hierarchies. In Grip’s first part [the book was initially released as two risograph-printed volumes], the hero repeatedly encounters other women that seem to live fearlessly, who encourage her development while avoiding maternalism. In one such scene, the protagonist drops a bunch of plates in a trial of her ability to spontaneously produce additional limbs and other body bits. In response, the presiding hostess, another master of dexterity and cash registry, looks on lovingly, and the scene then…moves on from the incident, resuming the hero’s trials with her abilities while working as a server. The hostess recognizes the hero will better develop her abilities through trial-and-error and gentle support rather than hostile reprimands or micro-corrections in behavior.

The typical super power fantasy would eventually pivot the narrative towards the hero deciding that the responsible use of her powers would be crimefighting. That path never comes into view for the protagonist however as she decides to live out the hostess’ dream of visiting a mountain and is taken there by another woman. Initially it seems that this change in locale might be temporary, the equivalent of Bruce Wayne’s pre-Batman years of travel, yet the rest of the book exclusively features the protagonist’s mostly solitary time in this mountain region comprised of woods, fields, and cliffs. There, she further extends the reach of her ability through constant experimentation, communion with her ancestors and comrades, and contemplation of the natural world. The tension in the second part emerges from the protagonist’s engagement with ever more impressive feats of manipulation. The hero clearly revels in her power, evidenced by the recurring thin smile that emerges whenever she flexes her abilities, whether they’re devoted to deconstructing a tea kettle, splitting wood into the bones of a home, or converting flowers into edible material.

Grip also shifts the political imaginary of where comic makers align themselves among class strata. Though comic creators are overwhelmingly among the poor and working-class, as well as often carrying intersecting identities that further marginalize them, they have maintained an image within the mainstream popular imagination as being largely middle-class, or even rich [white men]. I think this happens because many of the formative underground comix from the 1970s and 80s that achieved mainstream success (i.e. comics read by snobs that say they don’t read comics) tended towards depictions of blue-collar folks and craftspeople as background figures, lacking the assumed complex interiority and ennui of their protagonist. Westvind’s book, in contrast, carries an abiding respect for all workers in her renderings of people laboring.

The mostly women-coded bodies in Westvind’s book don’t play to the male gaze. They have bulk and musculature unconcerned with stereotypical femininity, and they dress with prioritization for labor and comfort. When a panel features a woman, they’re busy with whatever task they’re engaged in, not stopping to offer the reader a pinup to titillate or endear the reader to them.

Westvind’s feminist view of bodies also extends to the men-coded characters in Grip, like the cooks in the diner from the book’s first half. Although sweating, the cooks’ depiction don’t inspire disgust or pity for their chosen jobs. There’s no characterization of their movements as oafish or repulsive, but, rather, demonstrates an appreciation for what the cook endures—high temperatures, an onslaught of orders—in their work. Grip shows this through pages depicting the network of labor required to get a burger on a plate. In fact, the only person who ever appears as a caricature is the main character’s boss at the mailing company, who the reader first meets introducing the hero to her work station in one form, and then a few pages later as a buffed-out version of himself, sunglasses included. The subtext is that he has profited from the main character’s superhuman ability to malleableize objects in the material world to sort and mail items fast, and his consequential wealth has inflated his ego. The main character soon leaves the job to work as a server at the diner she frequents, working alongside others in similar class positions, the impression being that though she continues to have technical superiors, she’s not quite as susceptible to advantageous superiors able to financially advance from her labor.

Westvind’s drawing style reinforces this class connection, exemplifying that comics art is the result of a body at labor in addition to an intellectual product. Westvind does this through drastic perspective shifts in quick succession that sometimes impress a feeling more of being in the hero’s mind at work rather than the seeing work being done. These feats are not always clear in their depiction of what literally occurs to the item because they prioritize force and movement, maintaining a sense that energy is circulating between the item and the person manipulating it. Grip’s art reminds me of that story told about Katsuhiro Otomo where he colored an explosion in Akira dot by dot despite the labor required in order to imbue the explosion with the energies of each of those dots. Similarly, Grip’s art regularly calls attention to itself as the product of a body in motion, every page refuting doubt that what Westvind is doing is work. Though the story-ending motorcycle is impressive in its completed state, its completed image pales to the previous pages showing it come together from the earth, through the hero’s hands and mind, and toward remaking each element into something unlike its unprocessed counterpart.

Grip’s concern with labor also comes through in how time plays out when the protagonist is creating. Even though the hero possesses superhuman abilities, she also relies on care, precision, and will to complete her work, and Westvind regularly slows the action down to show how much work every detail requires. Near the book’s end, the hero begins her most painstaking project yet, building that motorcycle from scratch. Unlike the supply chains that dominate our world’s contemporary manufacturing, the hero goes through piece by piece to form her ideal cycle. After forming the motorcycle’s body, she starts the final unseen element. She melts a boulder, sifts through it for traces of precious metals then pounds the material with embiggened hands. The hero then stretches the material to extend its surface area and bends it into loops across a double-page spread. Finally, she takes the resulting coil between both hands and compresses it to the necessary size before inserting it to the motorcycle’s engine; this final, seemingly minuscule, part having taken seven pages of matter manipulation to produce.

What Grip leaves me with is a greater appreciation of the embodied and time-intensive work comic creators put in to make books readers typically quickly consume. Grip’s apparent infusion of Westvind’s bodily energies constantly calls readers to attend to the labor involved in making every line and piece of color. As workers everywhere face an increasing crunch, Grip calls on readers to recognize the humanity of craft workers in frontline communities. Grip gives readers a glimpse of a fantastic world where the word “work: does not inspire Garfield’s feelings about Mondays, but the opportunity to participate in co-making and shaping the world.

Images of Lale Westvind’s Grip are courtesy of Perfectly Acceptable Press.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply