Celebrated illustrator Art Young’s journey through hell, metaphorical as it may have been, was nevertheless a lifelong experience, beginning when he was a small child in Monroe, Wisconsin, where he was first exposed to a book of Gustave Dore engravings depicting scenes from Dante’s Inferno. To say it made a lasting impression would be quite an understatement.

In 1892, Young, by then a well-established newspaper cartoonist, gave Satan’s domain a go himself for the first time with Hell Up To Date, an illustrated ‘travelogue” of sorts depicting a smooth-talking big city newspaperman chatting his way through the fiery depths — and while I haven’t seen the story in its entirety myself, it seems as though Young may not have been entirely satisfied with how it turned out, given that he essentially re-worked it (to the point where several illustrations were re-drawn versions of the originals), with some additional material added, and published it in 1901 as Through Hell With Hiprah Hunt. As a showcase for Young’s stylistic evolution, it makes for an interesting time — his line at this juncture is much cleaner, his direct evocations of Dore’s woodcut engravings achieved with greater simplicity — but the only notable narrative difference was the swapping out of the comedic figure of newspaperman with titular revivalist preacher Hunt.

One could be forgiven, at that point, for believing Young was through with Hell, his career taking him from Chicago’s daily newspapers to the seminal Greenwich Village counterculture publication The Massess, but no — he wasn’t done, not by a long shot, even though he eventually became as well-known for his socialist views as he was for his drawing. Fast-forward, then to 1934 and what would be not only his last trip to Hell but the final major work of his storied career altogether: Art Young’s Inferno.

This is a remarkably class-conscious work that nevertheless doesn’t have the word “socialism” in it even once — Young perhaps judging his affiliation with the philosophy being a given in the minds of most readers at that point — it stands as being perhaps even more relevant now than it was at the height of the Great Depression and if that’s not a depressing summation of our current state of affairs, then I don’t know what is. Sensing (if you want to put it kindly, seizing upon if you choose to be more mercenary about things) its direct applicability to the here and now, Fantagraphics has just re-issued it in a handsome hardcover edition reproduced directly from Young’s original pages — be on the lookout for brushstrokes and penciled “margin notes” — and it’s hard to say which description, if you need to pick just one, suits the new volume best: labor of love or revelation.

Fortunately, we’re not obligated to choose, so we can just say it’s clearly and obviously both. And while the informative foreword by this edition’s curator, Glenn Bray, and the introduction by noted graphic designer Steven Heller set the stage and provide vital context, it’s still the work itself — its presentation now as near to the definition of “impeccable” as is probably humanly possible — that blows the mind, engages the heart, tugs at the funnybone, and stirs the senses.

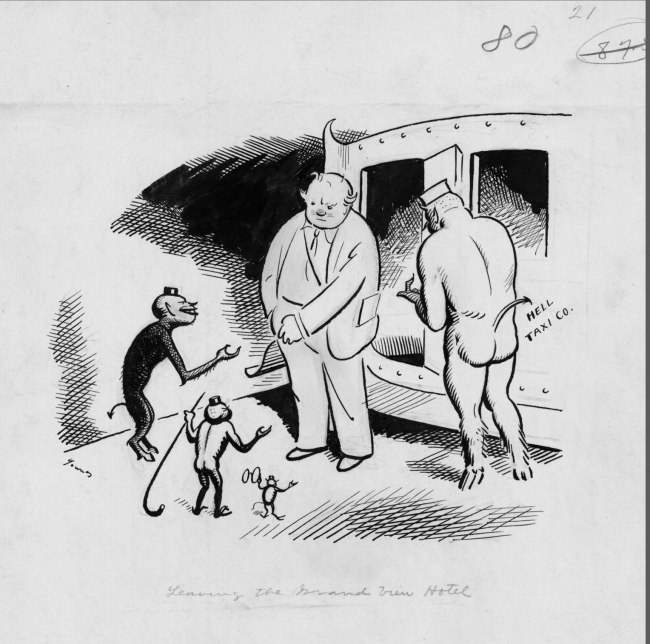

In Young’s Depression-era iteration of hell, the “monopolists” have taken their place alongside Lucifer himself as lords of the realm, and garden-variety sinners are relegated to sleeping in the streets while caves are rented for princely sums by the infernal oligarchs who have privatized everything in sight, the almighty Hell Water Power Co. standing as the most powerful corporate entity of the bunch. What happens when the capitalists are given the eternal “reward” they so richly deserve for their greed and avarice in this life? They continue to do the only thing they know how to do in the afterlife — gobble up everything in sight, exploit all the natural resources they can get their hands on, and start charging outrageous sums for everything to the ordinary folks.

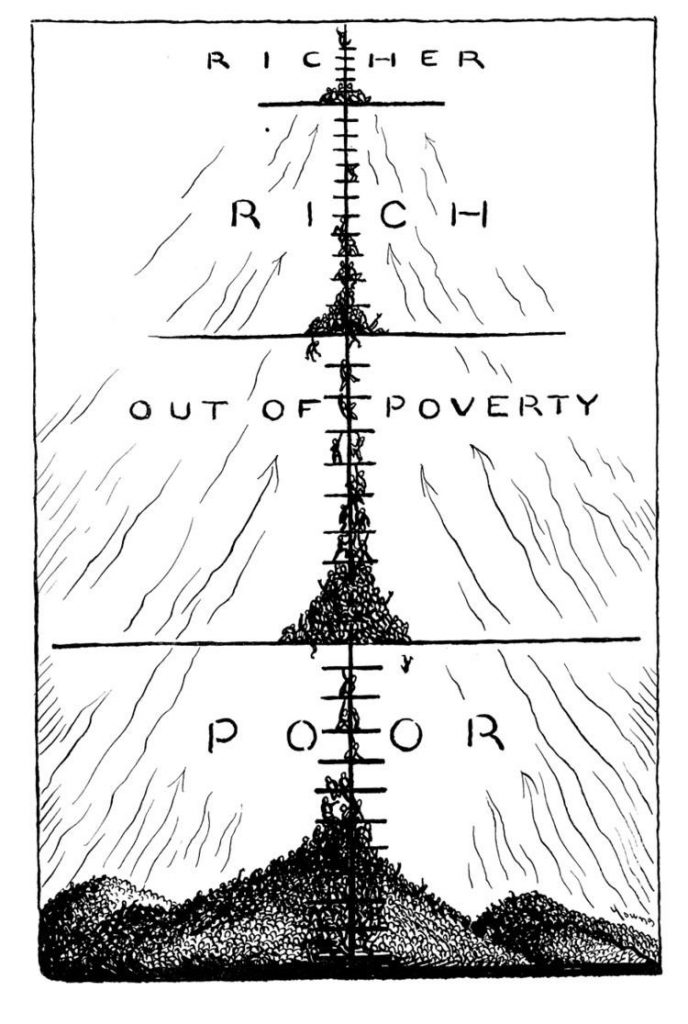

If you subscribe to the Christian conception of hell, it sounds bad enough as is — everlasting fire and torment and all that — but how about trying to navigate all that while you’re poor, to boot? Yes, friends, as with everything else, even the fiery depths become worse when you put businessmen in charge of it, and under their unforgiving rule, cool breezes sell for a dollar each, the fire department charges for the water they use to put out blazes, parks have admission fees, and hospitals only treat you for burn wounds if you can pay for it. In the tradition of Dante and Dore, everybody’s pretty well naked, but the masses couldn’t even afford to put shirts on their backs if such a thing were allowed. Social stratification is set in stone, the haves keep having more, and the have-nots are stuck fighting over the few scraps that drop their way. It’s tragic, it’s harrowing, it’s worse than Hell has ever been — and, of course, it’s also (sorry, but) hellishly funny in the way that only all-too-real satire can be. Case in point: gentrification is now so out of control that even Dante himself no longer recognizes the place and yearns for its lost “charm,” and physical tortures are being phased out in favor of mental anxieties, as working-class denizens struggle one against the other for that ever-elusive chance to “move up the ladder,” this illusory carrot on the stick bringing out the worst in people far more effectively than flaying or flogging ever could.

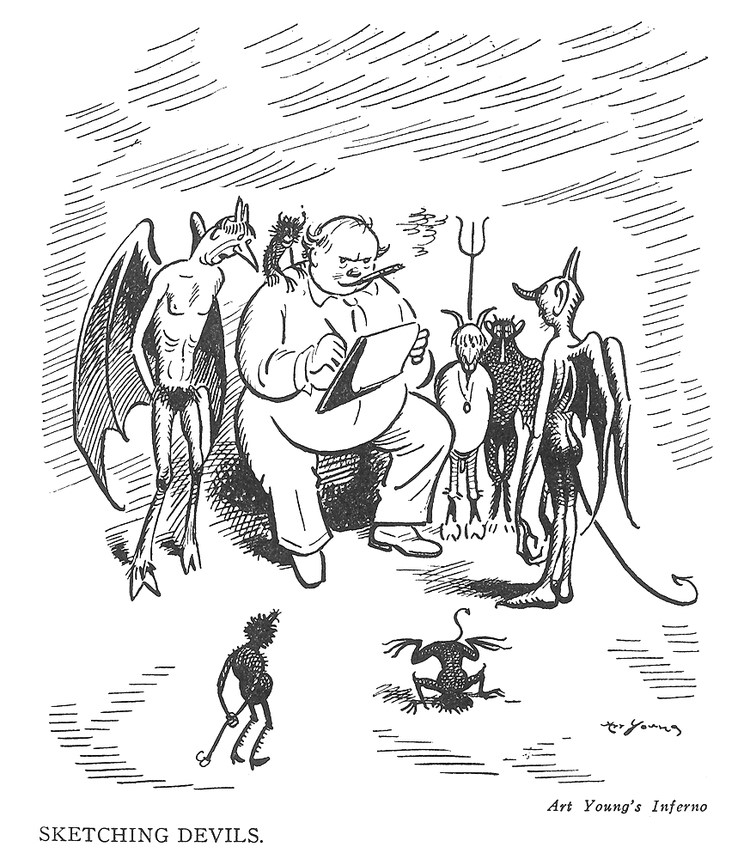

And while the essays accompanying the illustrations, written by Young and his “friend, admirer, and attorney” (possibly in that order?), Charles Recht, go some way toward expressing the uniquely capitalist deprivations of this new Hell, it is still Young’s illustrations that carry the load, his meticulous line, ingenious shading, and inventive figure drawing depicting a hell that chills you to the bone even as you can’t help but laugh at it. He perhaps saves his best for last — when no less than Satan himself is squeezed aside by the captain of industry — but the entire journey is something to behold, indeed. Dante and Dore would be proud of Young’s achievement, I’m almost sure of it, just as I can imagine Young would no doubt be overjoyed at this lush, elegant new edition — even if he’d be understandably crestfallen by the fact that it’s every bit as contemporary an analysis of the class structure in 2020 as it was in 1934. Hell eternal, indeed.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply