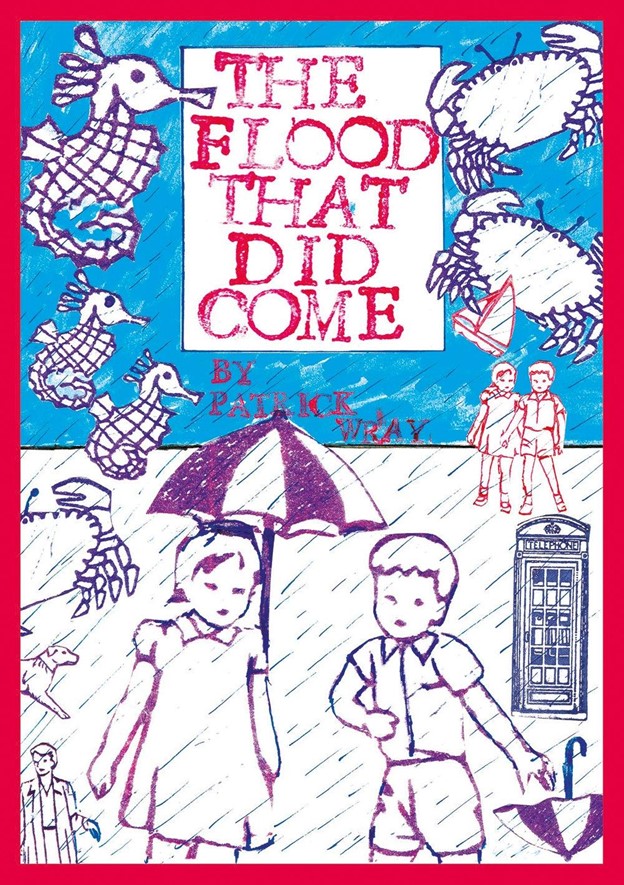

Following in the proud tradition of some of the more experimental releases from its publisher, Avery Hill (think George Wylesol’s Internet Crusader or Abe Christie’s Swear Jar), multimedia artist Patrick Wray’s debut graphic novella, The Flood That Did Come, leaves a mark by dint of both its content and approach, its formal ingenuity being every bit as critical to its success as its tantalizingly oblique story. There are gaps in our knowledge left there deliberately by the author, but enough is on the page for us to limn out most of the particulars we need in order to form an impression of both what’s going on and how Wray is going about communicating it — and impressions, literally and figuratively, are precisely what he’s all about creating.

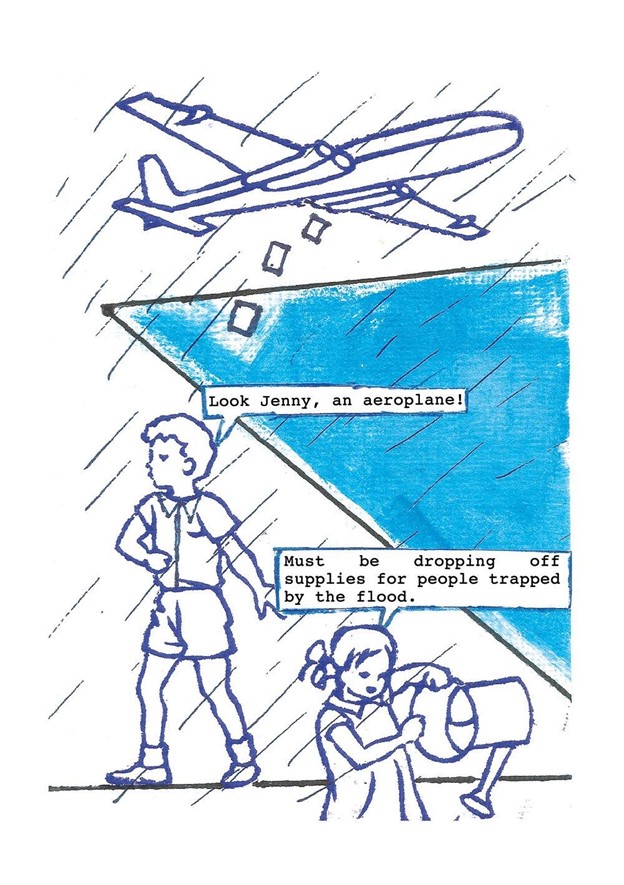

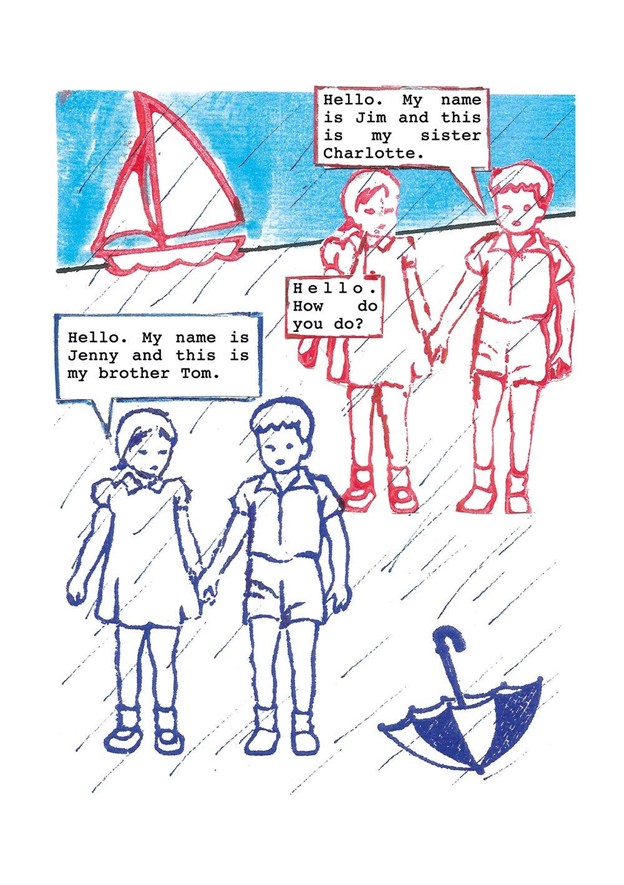

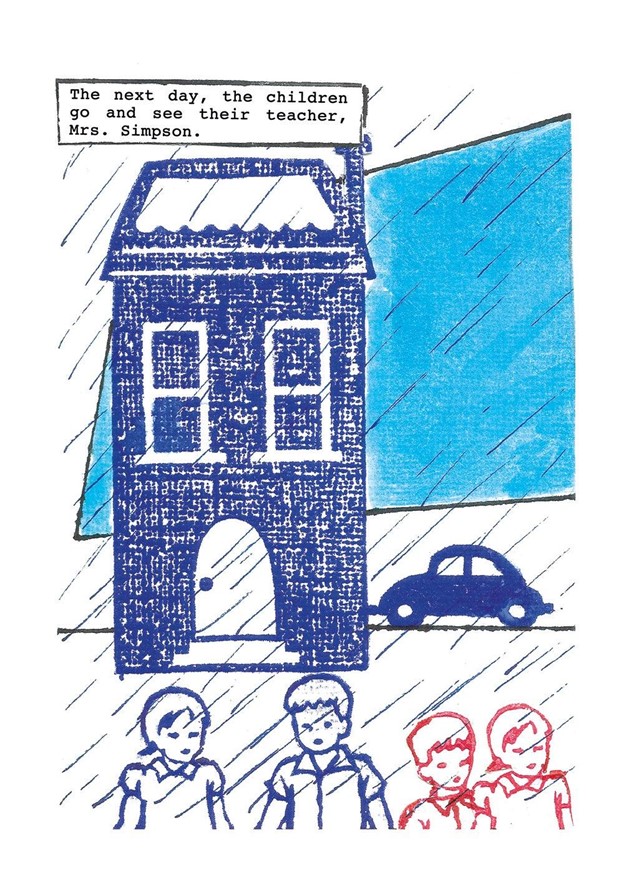

Consider that this slim book isn’t so much “drawn” as it is assembled and structured, with Wray relying on imagery created by woodblock stamps and a limited palette of inks. As a conceit, it’s certainly clever on its face, but it’s also thematically appropriate, lending a sense of unreality, of substantiality that is either incomplete or at least compromised, that follows through into the entirely unnatural dialogue and the plot itself, which is heavy on concept, light on details. We know there’s been a flood — a deluge, even, and likely more than one — that has left most of Britain submerged at worst, uninhabitable at best, but the sheltered “Home Counties” suburban hinterland of Pennyworth has largely been spared. Life goes on as near to normal as possible within this privileged hamlet, and that sense of relief tinged with privilege is ever-present in the attitudes of youthful brother and sister protagonists Tom and Jenny — until their doppelgangers, Jim and Charlotte, show up, heralding the opening salvo of an “eminent domain”-style claim from the nearby village of Brook Falls. And that’s when the shit hits the fan in that traditional cutting, understated, entirely British sort of way.

If you’ll recall Phil Ochs’ spoken introduction to his satirical and prescient folk classic “Love Me, I’m A Liberal,” he talks about the kind of nominal “left-winger” that is, in his words, “ten degrees to the left of center at the best of times, ten degrees to the right of center when it affects them personally,” but is still desperate to be thought of as one of the “good guys” (predicting Clinton/Biden-esque, Wall Street-friendly Democrats five decades early), and that’s certainly a fair summation of the outlook of Pennyworth’s citizenry. They are, after all, oh so concerned about the well-being of their fellow countrymen and women — that is, until they start showing up. One might recall that Ochs went on to sing, “I love Puerto Ricans and Negroes — as long as they don’t move next door.” That only slightly applies here, though, and not just because these folks are all white: for one, unlike the Black and Hispanic Americans moving into formerly all-white neighborhoods in the late 1960s, the people of Brook Falls aren’t looking to live side by side so much as they are to take over, dusting off archaic laws in order to buttress their claim to dominion over Pennyworth, nor are they entirely without resources. There is talk of advanced technology, for one thing, even if the robots, when they do show up, are as deliberately archaic in their appearance and function as most everything else on offer here — but bubbling under the surface of all this polite conflict is the central question of whether or not these communities can simply … ya know … co-exist rather than come to blows. And finding a way to do so might be especially crucial since it appears another flood may be imminent.

There is, then, an awful lot to unpack here, and even if the story is set in the year 2036, its concerns are very much steeped in the present day: environmental catastrophe, political collapse, social and economic stratification, resource scarcity, “build the wall”-style isolationism, the soullessness of suburban existence — this book should be required reading in all gated or “master-planned” communities.

But what hope does a group of plucky youths have when they’re charged with the task of dismantling the entire edifice of basically all of the failures of the “grown-up world” in one go?

Wray’s deliberately naive art and writing style (oftentimes the adults and kids alike sound like they’re quoting verbatim from public safety-style brochures and announcements), and his positioning of youths as the voices of unintentional wisdom seem to be advancing a view that naivete and innocence are the only way to avoid catastrophe — check that, the only way to avoid another catastrophe — and, in a pinch, that makes for a quaint moral. Yet, somehow, a quaint moral seems entirely apropos within the scope of this project, perhaps even a necessary component of its raison d’etre. Water, after all, isn’t the only deluge on offer in these pages — delightful contradiction, a visual and narrative anachronism, and a know-and-wink deliberate lack of sophistication are all in plentiful supply as well, and even if what Wray has wrought here may not (hell, likely won’t) necessarily register with every reader, there’s no denying that it’s a truly singular experience.

Granted, that may be a fairly qualified endorsement of The Flood That Did Come, but it’s in no way an unenthusiastic one. Quite the contrary, in fact. For those with sensibilities broadly considered to be “off-kilter” and who enjoy seeing tried-and-true themes explored via new and interesting artistic methodologies, this book falls somewhere between a clever, largely successful experiment and a truly innovative, borderline-”outsider” art. As mentioned earlier, Wray concerns himself more with making impressions than he does hard-and-fast statements, so I’m still in the process of deciding precisely how much I like what he’s created here, but like it I surely did — and the extent to which I find myself pondering both what it does and, just as importantly, how it does it should be proof positive that the impression it makes is both deep and lasting.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply