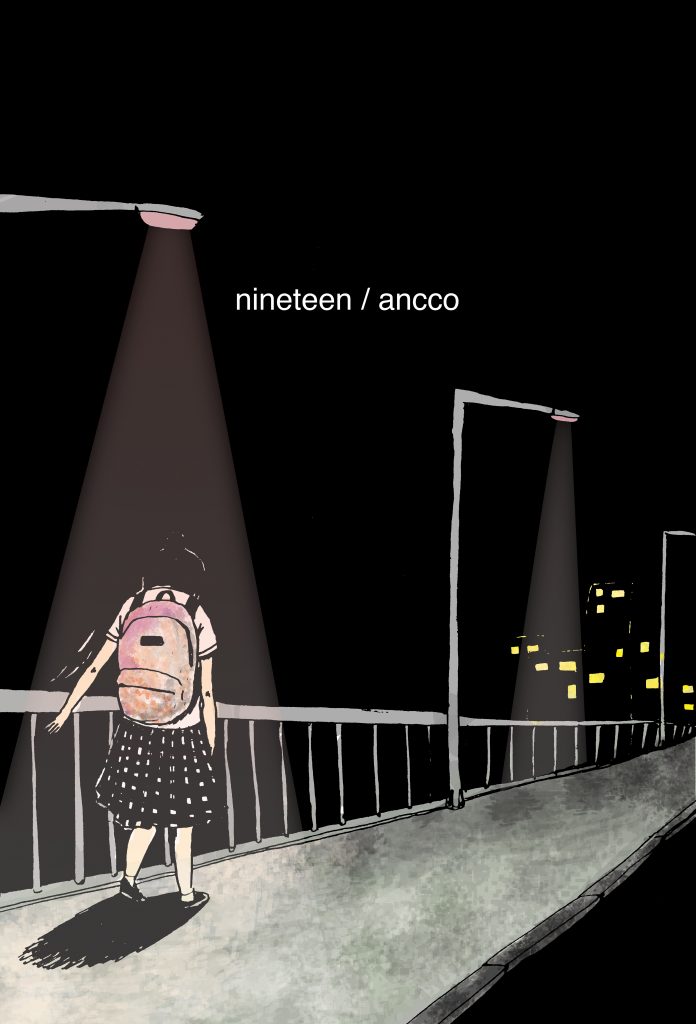

Originally published in Korea in the late aughts, Ancco’s Nineteen is a collection of semi-autobiographical short stories that describe the nervous liminality of late adolescence. Her tough-talking teenage protagonists are at turning points, staring down the barrel of adulthood with little idea of what’s next or how to proceed. Their families—both the parents and the children—struggle with various dysfunctions, which include cycles of abuse and addiction. This makes growing into a fully developed, self-sufficient adult all the harder and more painful to attain. As they messily negotiate the people they are/will become, they act out, rebel, and suffer the consequences—come what may. Ancco’s hard-edged tell-it-like-it-is narratives, sprinkled with sardonic humor, meld perfectly with her grittily detailed drawings, resulting in a work of cracked beauty.

Though it’s not stated, my guess is that the stories are presented chronologically. I say this because the first few feature rougher, more jagged character designs, with many minute details and much crosshatching, delineating gritty urban streets and modest middle-class apartments. Generally speaking, as cartoonists progress in their art, they tend to simplify or streamline their visuals. Ancco’s cartooning gift is evident from the very start, and it’s gratifying to see how her talent evolves over the course of these pages.

The early stories focus squarely on themes of familial ties, which, as ever, are burdened with issues. The opener, “Mom,” begins with its heroine, Boram, visiting her stricken mother in the hospital. It then flashes back to scenes from their fraught relationship, which alternates between tenderness and anger.

The mother is shown as highly supportive of Boram, especially as Boram studies for her upcoming GED test. Although Boram does study, she also goes on drunken binges with her friends—the kind of binges that ultimately result in vomiting in the gutter. In one scene, mom confronts her daughter post-binge and berates her: “Why are you doing this to me?” Boram’s pointed reply: “You think you have the right to say that to me, Mom? Worry about yourself.” Her mother responds by slapping her. Ancco then cuts to the next morning, where Boram awakens with a hangover, only to find her mother has prepared a full breakfast for her.

Later still, mom is stumbling around the house drunk, cooing to her daughter as if she were a young child (“Is my Boram studying?”), much to Boram’s disgust. It’s implied that these cycles play out over and over between the two, though whether Boram has inherited her mom’s alcoholism or she’s just acting out behaviors she’s familiar with is not known. My guess is that she’s indulging in the time-honored teenage tradition of testing out limits, of seeing what she can get away with. At any rate, we understand that the two are bound by mutual love, pain, and feelings of guilt and shame.

“Grandma,” the second tale, continues along similar themes, though it features a different, nameless young protagonist (which strengthens the universal feel of the troubled families in Ancco’s work). Here the young woman describes a loving, empathic relationship between her and “Granny,” but, as in the first story, the specter of alcoholism clouds things (here it’s granny’s drinking that’s problematic). But the love and support are still evident.

Ancco’s character work in both of these stories has an arresting, off-kilter immediacy. She draws her cast with very large heads, small bodies, and shortened arms and legs. But the grotesquery doesn’t feel misanthropic (as in say, the early work of Daniel Clowes), it simply emphasizes her characters’ awkward imperfections and common humanity. In later stories, her line becomes more confident but the awkward quality (happily) remains.

A later story, “Wild Roses,” explores another grandmother-granddaughter relationship, though this time the emphasis is on the grandmother’s attempts to be involved in her family’s lives, particularly that of the granddaughter. But the grandmother is generally dismissed. Her thoughts or observations are thoughtlessly trivialized, especially by her own daughter. The ending etches out the grandmother’s loneliness and isolation in heartbreaking relief. The fact that her granddaughter recognizes that she’s neglecting her gramma and feeling bad about it—but not making the actual effort to do much about it—rings painfully true. Empathy is a start, but, by itself, it’s not enough.

The stark, brutal titular story offers us yet another protagonist, Kyung-Jin, who, like Boram in “Mom,” lets off steam by going out drinking with a couple of her high-school friends and getting into trouble at school. When a teacher catches her drawing an X-rated comic instead of doing her schoolwork, she slaps Kyung-Jin right across the face. Even worse, after coming home late after another night of troublemaking with her friends, Kyung-Jin is viciously beaten by her father.

Afterward, sitting with one of her pals out in the dark, with a gash on her head still bleeding, she has a good cry—then immediately minimizes the incident: “I don’t ever think or worry about my life…Even now I’m just crying because it hurts, I’m not thinking about anything else. What a joke…” As distressing as her situation is, it’s not clear that this reaction is healthy or unhealthy. Is it strength, resilience? Or is Kyung-Jin just numbing herself, giving up? Or a combination of the two? Ancco lets the reader decide.

A common thread throughout these stories is this lack of resolution, this liminality. The stories don’t so much wrap up as just stop, reflecting the fragile sense of self of each teenager, the question of “what next” hanging heavily over each like a shadow. To Ancco, I suspect, Teenagedom is in itself an open question.

“Do You Know Jinsil?” is another tale featuring a trio of bawdy teen girls out carousing one night. This time, the story focuses on peer pressure and scapegoating. We don’t meet the character Jinsil until the end of the story, but, by then, we fully understand she is like Stephen King’s Carrie, the butt of every joke. The main girl in the story is highly uncomfortable with Jinsil’s victimization and doesn’t add to it, but when given a chance to reach out to Jinsil she doesn’t take it. Ancco does a great job with this moment, creating a recognizable scenario and populating it with three-dimensional characters, opting for subtle realism rather than Afterschool Special didactics.

Rounding out her teen-girl/family stories, Ancco includes an ancillary piece called “Life,” a first-person narrative (adapted verbatim from a real internet post), featuring a young gay man who has just discovered that he is HIV-positive and understandably in emotional turmoil over it. Given his paralysis at the thought of talking honestly with his family about his diagnosis, the story fits in well with the general sense of teenage malaise and lack of agency in the rest of the book. It is, however, the one story in which sexuality comes into play.

In another piece that seems to be straight auto-bio, “My Dogs and I,” Ancco offers a simple scenario of a young woman feeding her four dogs outside on a cold night. She makes a sort of ritual of it, feeding them in her own peculiar order. Bear gets his first: “Since you’re the biggest, you get the most,” followed by Kyung-Ja, who “just had a baby, so she’s next.” At one point she cries a little over another dog that has passed: “I wish Jindol was here.” The ending features a whimsical moment with her waving goodbye and the dogs following suit. It’s a sweet little comic with a slightly dank atmosphere. You can practically feel the cold night air offset by the warmth of the fire she has built for her pack. The ease and simplicity of her relationship with the pups contrasts strikingly with the tumultuous human relationships depicted elsewhere.

Among all her dramatic stories Ancco intersperses a series of short, diary-like comics, each about four-pages long and each emphasizing her dryly self-deprecating, sometimes downright cranky humor. These comics, drawn with much less background detail than the teen stories, lighten the load and help round out the overall collection. They also depict the aftermath of the teen stories: no longer under the thumb of parents and teachers, you are free to screw things up all you want. Only now you have to fully accept the consequences. These stories include: “I’m Sorry,” which describes a disastrous haircut she tries to give her boyfriend; “Me and My Guitar,” which relates her clumsy attempts to learn to play the instrument; and “School of Kyung-Jin,” in which she talks about her regular day-to-day as an actual young adult.

In my favorite, “Happy New Year,” she muses on aging: “To my surprise I turned twenty-four.” An interesting factoid she shares is that in Korea people turn a year older on New Year’s Day, instead of on their birthdays (at birth, a person is considered to be one years old). She notes that she always seems to be the direct opposite of the somewhat glamorous lady that she’d always imagined she would become. She muses that when she finally reaches inevitable life milestones such as getting married or having a baby, they will seem unreal (“How can I be having a baby?”). It’s existentialism lite, and it’s all funny and relatable.

“Happy New Year” ties in somewhat to the closing story, the ten-page “I’m Off to Geomun Island,” which is about the heightened expectations Ancco brings to a weekend getaway and the inevitable disappointment that follows when things just don’t gel satisfyingly. The ending is fairly expected but it’s still amusing.

In exploring the many dimensions of late adolescence with her unromantic yet always sympathetic eye, Ancco clears away the gloss of too many Hollywood and YA fantasies and captures the weird Jekyll-and-Hyde quality of those unfurling years. These alternatingly grim and sweet stories ring with authentic lived experience and coalesce into a unified, satisfying whole. Read it and remember.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply