I’ve always considered Andi Watson to be a pleasant artist. Exceedingly so even. When I look at his pencil work on Love Fights or Glister, I find myself filled with the desire to boil water in a kettle and make myself tea and biscuits. Just looking at these simple (yet precise) lines gives me the sort of emotional comfort one needs in this day and age — a rest, a dream. Watson’s new release, The Book Tour, on the other hand, is not restful; it’s almost the opposite in fact, closer to being a nightmare. It’s still identifiably a Watson book, though, he has not shifted his style considerably since I last saw his work, only now he utilizes the same skills to make the reader uncomfortable.

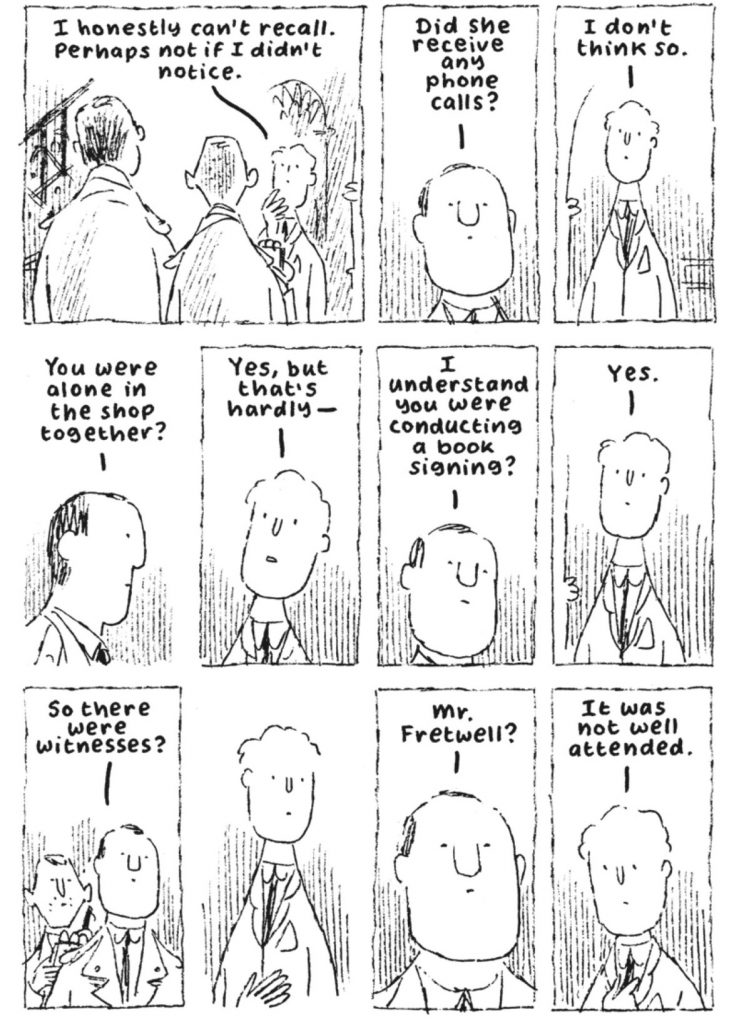

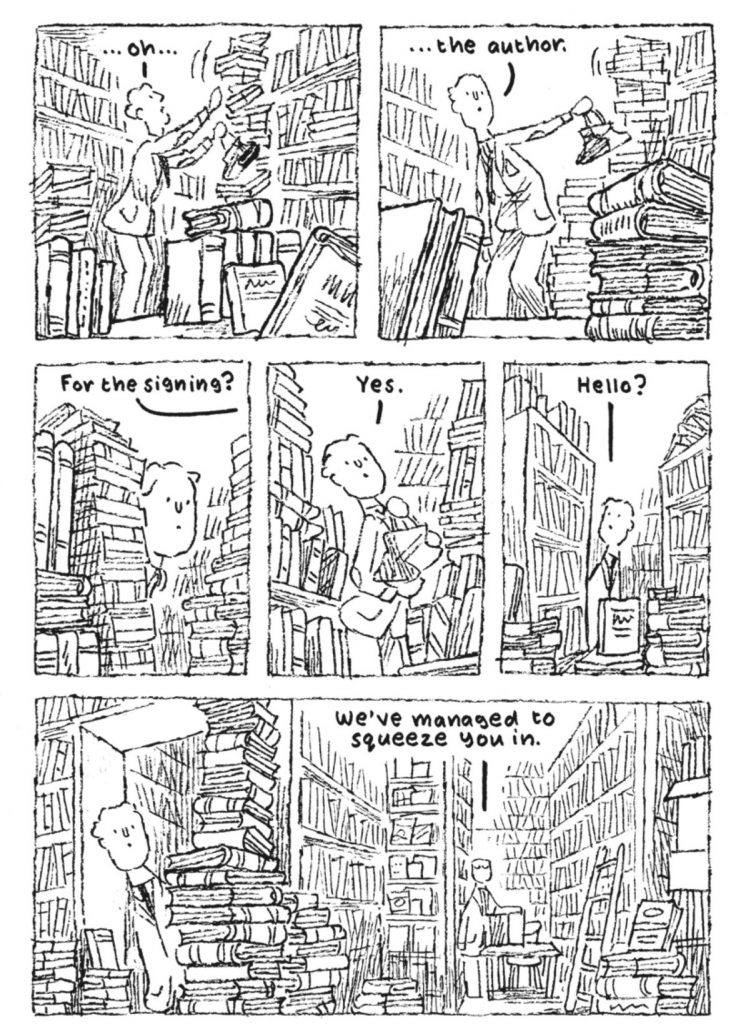

In The Book Tour, minor writer G.H. Fretwell ventures on a tour to promote his new book. Things seem to fall apart from the get-go: Fretwell’s luggage is stolen from him, no one shows up at the signing events, his publisher keeps extending the tour while trouble brews at home, the food is lousy. Also, there is a killer on the loose and wherever Fretwell goes everyone seems convinced he’s got something to do with it. The word Kafkaesque seemingly wrings itself into being. Indeed, the very name and description of the novel Fretwell wrote, Without K, evokes Kafka’s ghost.

Conjuring Kafka brings with it certain expectations. We have been told, repeatedly, that in the world of Kafka people are persecuted for no reason. Josef K, in The Trial, is generally seen as an innocent man, hounded by an authority he does not understand. It’s such an accepted piece of literary interpretation that I knew it before I even opened page 1 of The Trial. Just like one doesn’t need to crack the covers of Animal Farm to know what Orwell thought about Stalin.

However, just because something is accepted doesn’t make it true. In his memoir, The Discomfort Zone, Jonathan Franzen writes about studying in Germany and having his teacher force him to re-examine The Trial: “What was actually on the page, as opposed to what I’d expected to find there, was so unsettling that I’d shut my mind down and simply made believe that I was reading. I’d been so convinced of the hero’s innocence that I’d missed what the author was saying, clearly and unmistakably, in every sentence.” Josef K is abusive towards his neighbor Fräulein Bürstner, but the book is so persuasively written from his point of view that we simply fail to note these abuses unless they are pointed out.

It’s unclear whether Josef is ‘guilty’ of whatever mysterious crime he is charged with, but it is obvious that even if he was, he would fail to acknowledge it. In his own mind, he is forever the victim. Watch Orson Wells adaptation of The Trial (1962), in which Anthony Perkins plays Josef K just two years after he shot to stardom as Norman Bates, look at the constant nervousness and coiled anger within Josef. It is not just a simple story of a man being bullied, there is something sinister beneath that man’s surface.

Does Watson imply that Fretwell is a killer? No. That is never in doubt throughout The Book Tour. Yet we must not mistake his suffering for decency. Halfway through the book people are astounded to learn that he is completely unaware that there’s a killer on the loose, especially considering how often we see him bury his nose in a newspaper. Even the reader clocks the fact before he does. When asked about his ignorance of what appears to be national news, Fretwell can only answer that he only reads the literary supplement. Except he does not really read it, he’s simply searching for a review of his new book.

In short, this is an individual who is predisposed to assume that if things go bad, it is because the whole world is against him. Fretwell is an author with no interest in the world around him (a bad author, in short). His book, about a travelling salesman who suspects his wife ran away, is thus an echo of his self-centeredness and general distrust towards others. No wonder he has problems at home. To see yourself in him, in his persecution and pain, is also to reflect on your relation to the world around you.

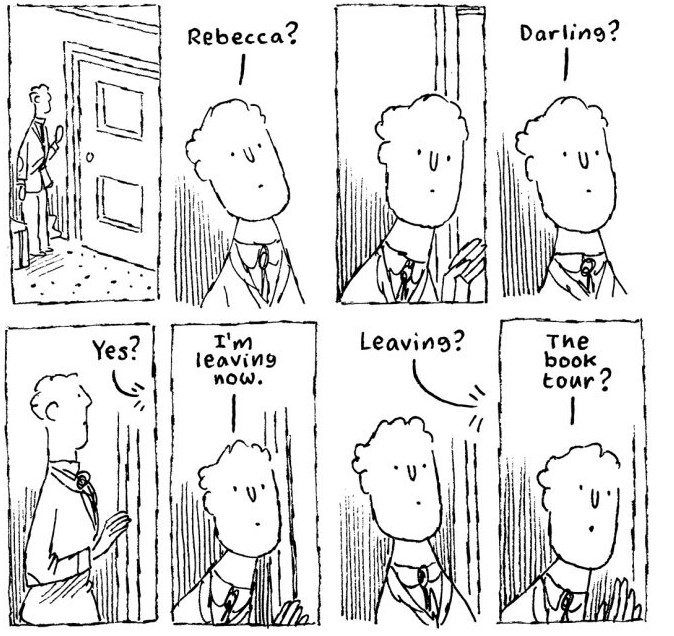

Watson still has the same straightforward esthetic developed throughout his previous output. The characters’ features are narrowed down to the minimal number of lines which renders them almost like caricatures. Faces are simple but extremely expressive. With a single line shift, Watson is able to change the whole mood of conversation: a fake smile (worn by a professional businessman) easily becomes a blank expression which then becomes boredom. Watson has iron-grip control of his figures and character acting; you can always tell what everyone is feeling (and how their words contradict their emotions). This is important because The Book Tour features a lot of talking heads, one long conversation piece after another. It’s a story about people constantly lying to one another, framed in the language of professional manners.

There’s a growing sense of dread and paranoia throughout the proceedings. Whenever we turn, the world seems to slide from “uncaring” to “downright sinister”. It reminds me, oddly enough, of Eddie Campbell’s work in From Hell, not so much in the visual likeness (Campbell is far more detail oriented and naturalistic in his characters) but in the mood it builds. From Hell was about a world that was utterly indifferent to the fate of the protagonists, harsh and cold on both physical and emotional levels. The Book Tour also depicts such a world.

With a few carefully framed shots of book stores, buildings, and small rooms Watson is able to suggest a sense of place and the mood it brings with it. The repetitive nature of the page layout and design (we are constantly witnessing events from the same angle) becomes an intentional tool of the artist. It’s a cramped and tight comic about a person who is constantly feeling strangled. After a while it appears as if Fretwell is in prison, and we are looking at him through the bars.

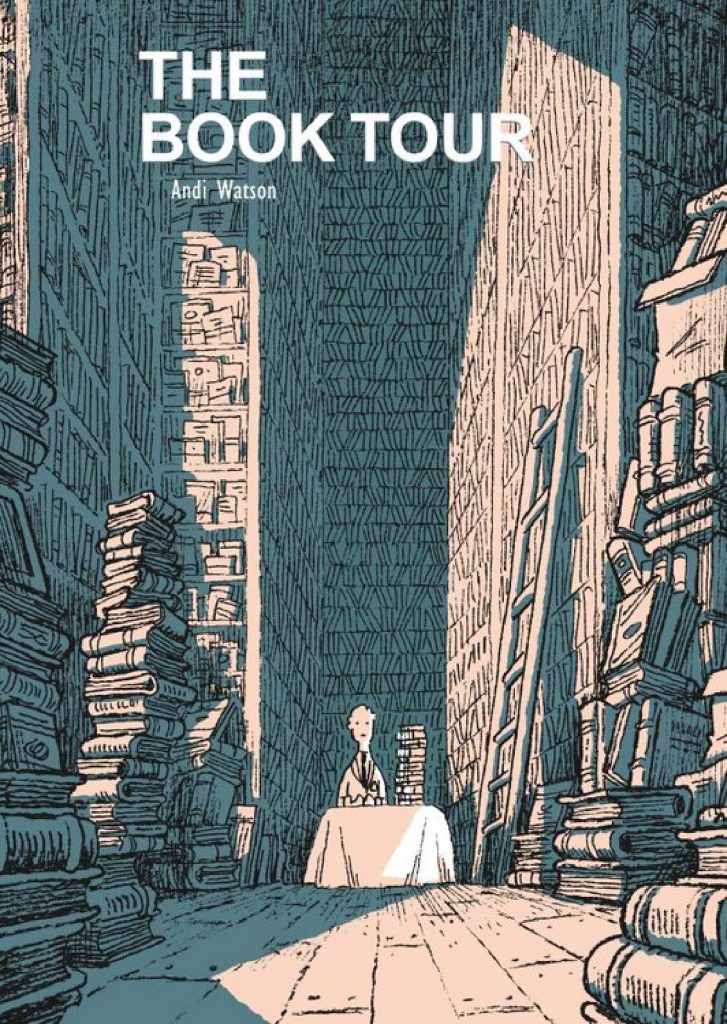

But if life is a prison, it is one Fretwell built around himself. Whatever happens to him, wherever events take him, he responds to them with the same blank stare and quiet indignity – never wanting to make a fuss, never shouting, never challenging. When he actually ends up in physical jail, it doesn’t feel like much has changed: his behavior, his routine, his thinking. Look at him on the cover, a man alone surrounded by a pile of books, looking straight at the readers without showing a hint of emotion. His strange and terrible journey didn’t change him in the slightest, it simply helped him to understand what he always was.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply