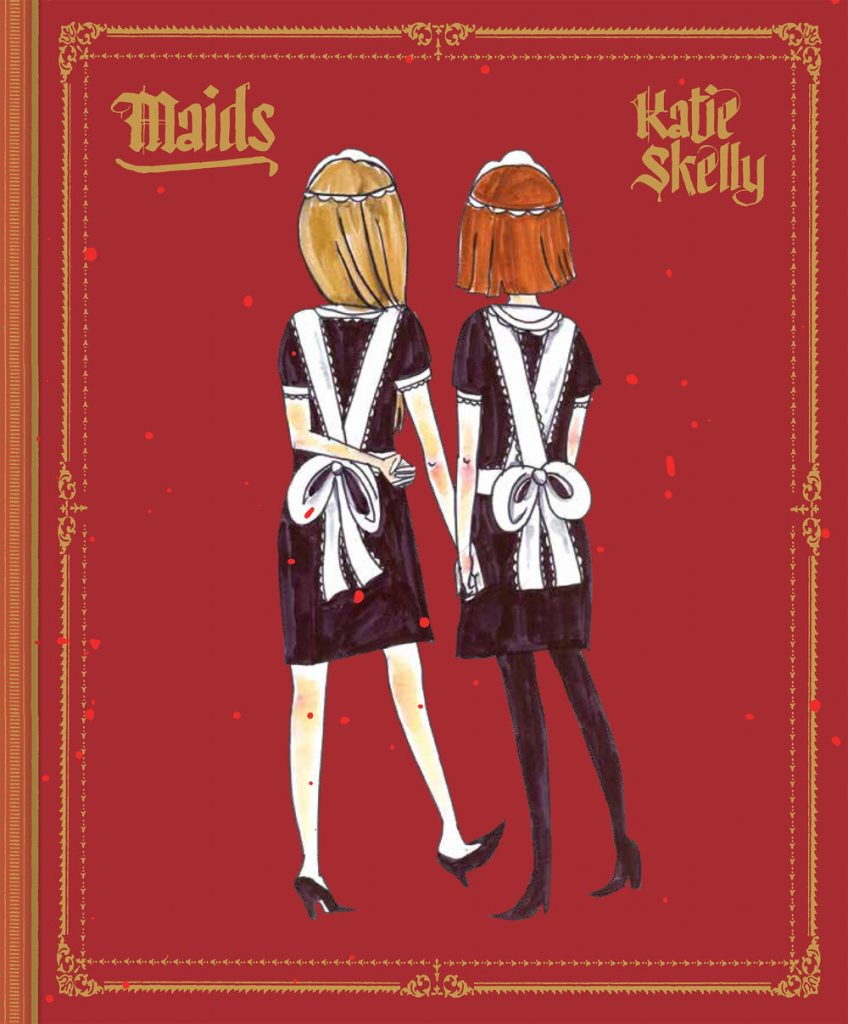

Katie Skelly is the most beguiling of cartoonists and Maids makes for her most deceptive work. Based on the killings committed by Christine and Leá Papin who savaged the bougie, moody, nasty wife and daughter of their employer in Le Mans, France in 1933; Skelly presents the events with cool elan while invoking Christ’s counsel, “Judge not, that ye be not judged” and thereby fashions a diabolic judgment-free-zone with no winners, only dead women.

Skelly has made her bones in the loaminess of exploitation; from Operation Margarine’s biker babes—Skelly’s choice to cast Chrisine as a blonde and Leá a brunette (IRL both were brunettes) winks at Margarine and Bon-Bon—on the hunt for thrills and revenge borne from fuckery of all kinds to the sex-positive Agent 9 in the collected series of erotic comics, Agency. The buckled, belted, and booted super vixens of Russ Meyer flicks and the giallo ingénues of Bava and Argento serve as muses, but True Crime is, perhaps, Skelly’s true medium. Her all-killer-no-filler digital only comic, Tonya, about figure skater and tabloid straw(wo)man, Tonya Harding, is Skelly’s most underrated (and unread) work. Tonya’s themes of body dysmorphia, trauma, and the toll of mental and physical abuse suffuse Maids. There would be no Maids without Tonya, even if such hyperbole amounts to little more than a mug’s game. Full Stop.

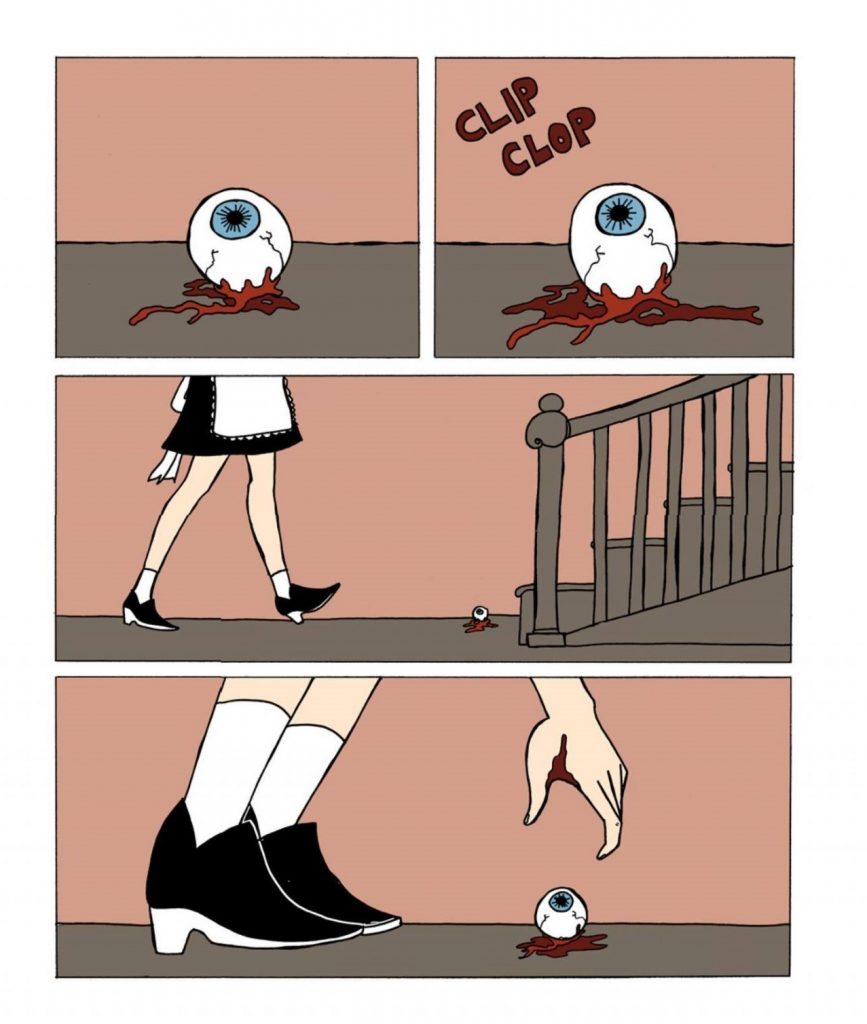

The first piece of information the reader learns in Maids is that someone (some body) is missing an eyeball. It’s not one of those comic eyeballs, a gag, round and glassy like a marble. No, this tad of ocular trauma comes with its optic nerve attached and there’s blood. Damage done.

As gross and gooshy as this eyeball appears, it’s a dodge. A guileless cartoonist to a fault, Skelly lives for misrule and she’s perpetually game to upend convention with charm, sophistication, and, yes, eyes wide open. She’s seen enough done-to-death eye opens—so de rigueur in film and certainly in “prestige TV” nowadays. Instead of mocking such a tried-and-true device outright, Skelly twists it, perverts it. As a storyteller, she knows the more hackneyed a trope, the more successful (again, think exploitation). The conventional image of the opening eye engenders “waking up,” a literal “woke” image. Skelly takes the opposite course; this isn’t a wake-up call — an open — it’s a close. Fin. It’s not an invitation; it’s a warning that foreshadows the coming storm and a ballsy bookend with the comic’s final eye-popping image.

Artful and artless all at once, this sequence of seven panels proclaims Skelly in full. Pure. Raw. Her line with its “all knees and elbows” idiosyncrasy appears simple, almost immature, but conveys confidence and cockiness in its overtness—all the information is set against austere backgrounds, in plain sight. And then there are those digitate “Skelly noses,” that stick out like finely tapered sore thumbs. Like the murderesses at the center of the story about to unfold, one dismisses Skelly’s straightforward style at their own risk.

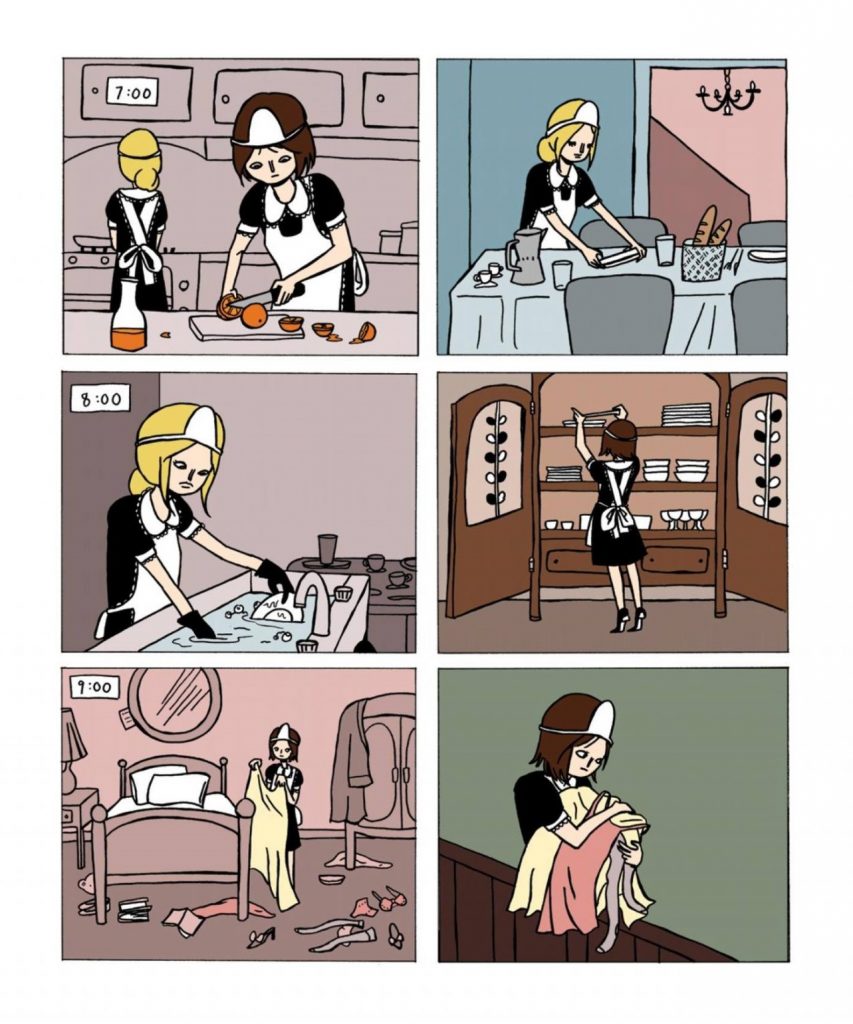

In the parlance of our times, Maids appears as yet another case regarding class, privilege, and wealth inequality. French citizens and the reigning intelligentsia (Jean Genet, John-Paul Sartre, and Jacques Lacan) at the time thought so too, as have generations of artists, writers, and filmmakers who have attempted to offer answers, nearly thirty by Wikipedia’s tally, not counting Skelly. Why did these working-class women, whom their employers considered inept, stupid, and meek, kill their social betters? Skelly is not mum on the matter—she’s team Papin, sure—but it’s not the only axe she’s brought to grind. Inequality of any kind (class or wealth) is not in question in Maids nor are the arduous hours the sisters work. In Chapter 4, Skelly hauls out the nine-panel grid, the cartoonist’s go-to for serious sequential story-telling, and spends four pages showing how the sisters spend their day. Yes, there are breaks to share a cigarette and a bite to eat, but there’s much more time spent cleaning than leaning. The repetition of those nine (thirty-six) panels brings home the domestic’s life in all its monotony. Around this sequence of tasks menial and culinary, Skelly sandwiches in scenes of verbal abuse from Madame Leonie Lancelin and her soon-to-be-married daughter, Genevieve. Neither woman acts like some fairy-tale caricature of “evil,” they are who they are given their status. During a dinner party, Leonie refers to the sisters as “rats.” She expects “another one will turn up any day.” Skelly doubles down on the disposability of the servant class when the family cat, an avatar for Leonie (her name makes for sly coincidence and killer irony), shows up during the party with a rat in its mouth. So these women are abusive and consider Christine and Leá lesser than and the cat is a cat … and? The reader expects (requires?) such behavior from the story’s antagonists, no? Skelly’s not passing judgment on any of these women, just providing facts.

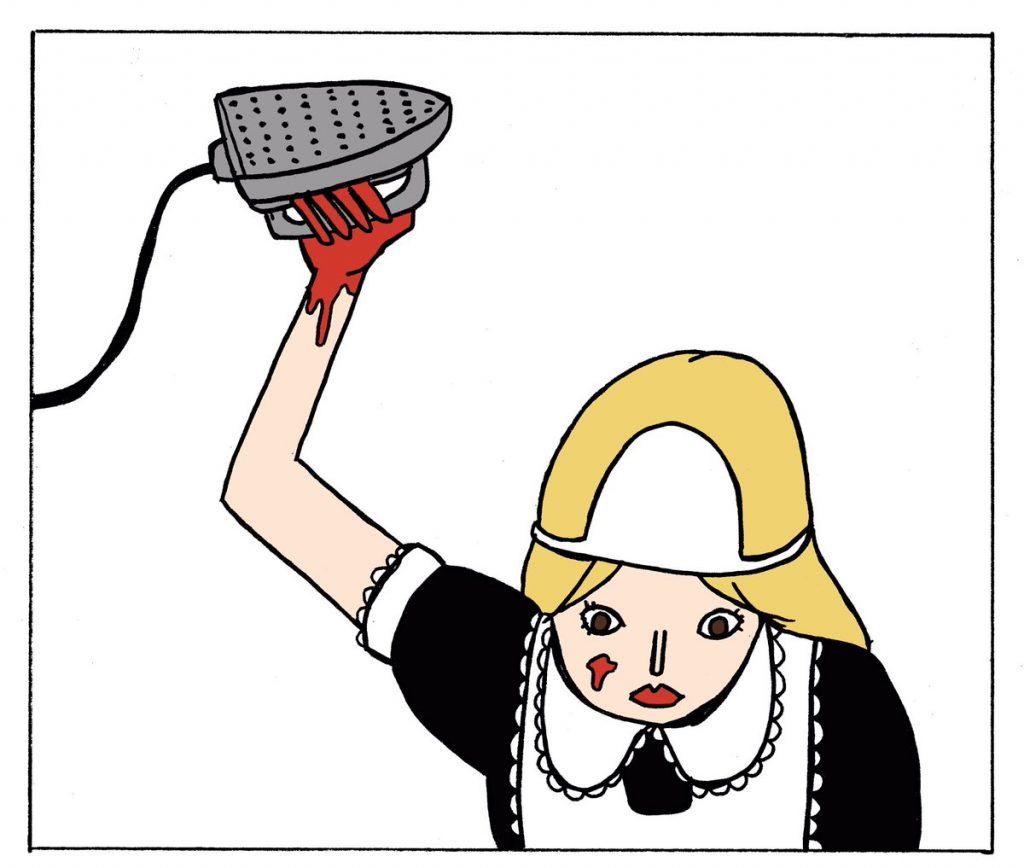

The traumas the Papins endured go beyond being bitched out by the “ladies” of the house and treated as subhuman. They’ve also suffered at the hands of an abusive mother and from the nuns at the convent where each was sent when their mother was done with them. The years of cruelty and neglect manifest in Leá as psychosis, perhaps even schizophrenia. Her mother calls out Leá’s hate for her when Christine is sent to the convent: “Look how hateful you are … your hands are all red.” Leá’s ‘red-handedness’ reoccurs when there is a threat she may be separated from her sister. Her final break happens when she sees Genevieve has stained her sheets and nightgown with menstrual blood. Genevieve dismisses the situation as yet another thing for the maid to clean up. The blood and Genevive’s reaction to Leá’s revulsion sends Lea from the room to Genevive screaming: “Are you slow?!” Alone and afraid of another possible pending separation, Leá’s (imagined) bloody mitts begin berating her, imps of the perverse, inciting her to violence, “I can be born of blood too … I’ve been trying to show you for years.” And like an invocation, Christine appears out of Leá’s fugue, a note, pure and easy. She steps forward to comfort, plan, and reckon.

If the sole purpose of Maids was to add a voice in a chorus of “eat the rich,” it wouldn’t be a comic by Katie Skelly. Like Tonya Harding, there’s more to the true crime story of the Papin sisters than a headline, Wikipedia entry, or what fits within a prescribed limit of characters. It would be easier (cleaner) to thrill to the bloodlust without conscience or consideration of the mental and physical strain of labor, the traumas and abuse visited upon the Papins or their sisterly bond. With one exception, there are no men in Maids. A reading through the lens of how women treat other women would be welcome, warranted. As would an analysis of how although the Lancelin women are better off than Papins, they are still women living in 1933, in a patriarchal system that treats them as little more than house cats. The themes of Maids contain multitudes and offer no easy answers because there aren’t any. Maids makes for a masterpiece for working women from a working cartoonist of the highest order.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply