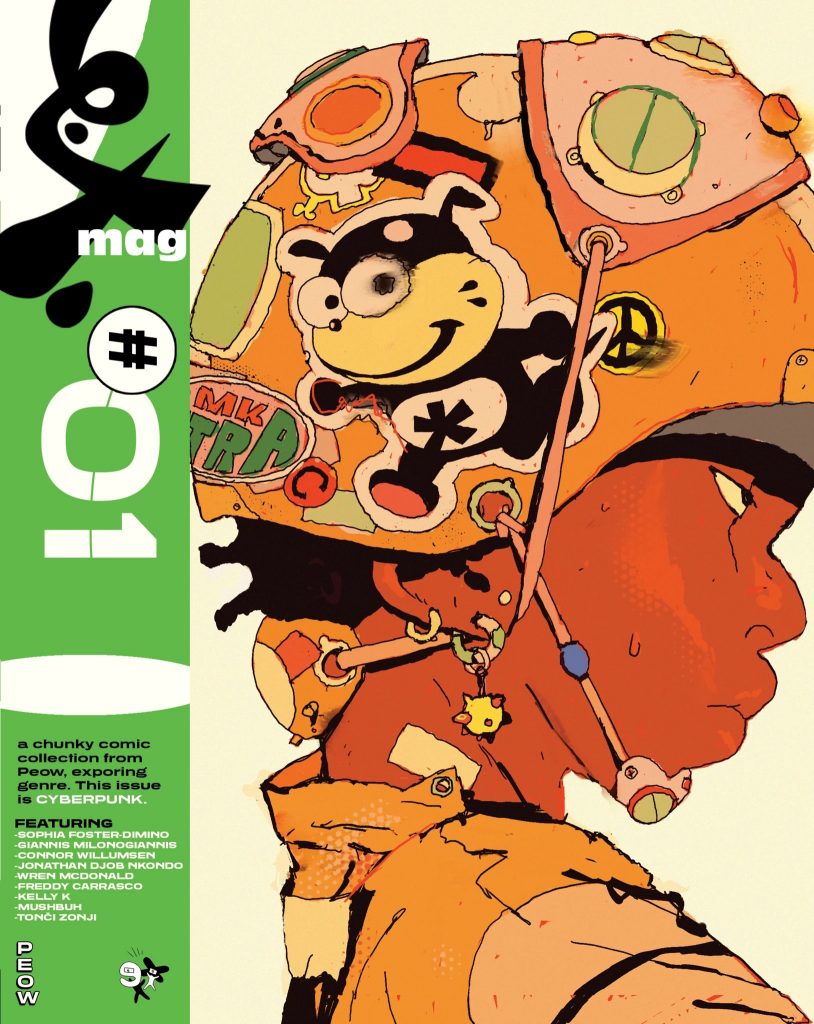

The first book in Peow Studio’s Ex.Mag, a new series of genre-focused anthologies, is focused on the theme of cyberpunk. This volume opens with the following definition “a subgenre of science fiction typically set in dystopian societies dominated by technology, often featuring artificial intelligence, cybernetics and antiheroes railing against distorted social order” and it bears the legend “high tech / low life” (paraphrasing genre prophet William Gibson). For Ex Mag, editor Wren McDonald has chosen a bunch of extremely talented creators for a dazzling showcase of science fiction tales. Individually, the stories here are mostly winners; but is this enough?

Ex.Mag #1 is as well-curated as anything else in the Peow Studio catalog. It’s a neat-looking package with a strong aesthetic sense and some very welcome touches that make it stand out as an anthology; the “artist interview cards” that end the book are a great way to explore the artists involved in a visual manner. The talent list is almost enviable, starting with McDonald himself (carrying on from his cyberpunk graphic novel SP4RX), and including Giannis Milonogiannis (Old City Blues), Jane Mai (P.E.O.W), Sophia Foster-Dimino (Sex Fantasy), and more. What this book lacks, however, is a mission statement; there isn’t a forward by the editor explaining what it means to make a cyberpunk collection in the year 2020. Unlike something as generic as “science fiction” or “horror,” which could be almost anything the author wants it to be, cyberpunk carries certain expectations.

The genre was formulated in the 1980s, not as some conscious moment (at least, not at first), but as a collection of popular breakout writers with shared thematic, or at least aesthetic, interests. These interests were very much of their time, especially the fascination (by mostly white males) with Japanese culture as something both exotic and novel. Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology (edited by Bruce Sterling) was published in 1986 and seemingly set both the tone and limitations of the movement: out of 12 stories in that anthology, 11 were by male authors, and all of them were white. While Japan had its homegrown crop of writers and artists, in America the genre quickly showed its preferred “type” and continued the tradition of “radical” anthologies, such as Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions, which dared to challenge the status quo but not the editor’s Rolodex.

Like other forms of radical art movements, cyberpunk was quickly consumed and commodified by the culture at large, becoming another aesthetic choice, a skin in a video game. Indeed, in the year 2020, when one googles the words “cyberpunk,” it is likely that the first result would not be the novels of Neal Stephenson and Bruce Sterling, or even the manga of Masamune Shirow, but the video game Cyberpunk 2077, a bulky production of a major studio, working to satisfy the largest audience possible.

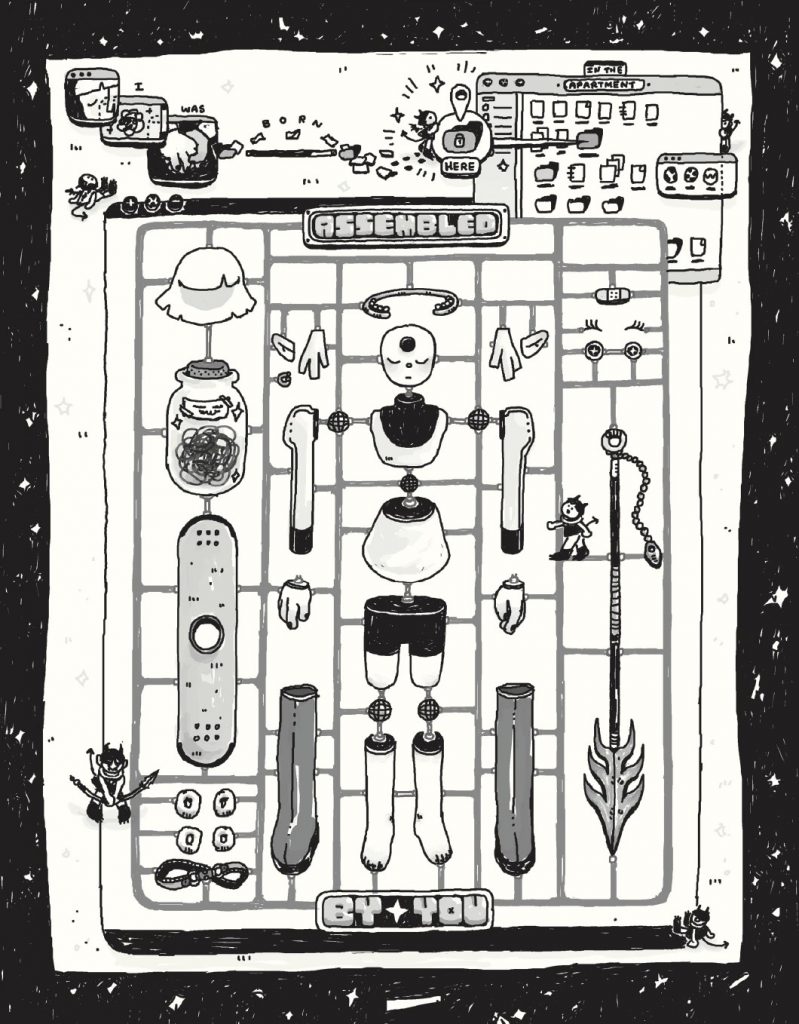

Against the crowd-pleasing tendencies of Cyberpunk 2077 and the monolithic nature of its predecessors, Ex.Mag #1 feels fresh and vibrant. The stories sprawl in different directions; most of them don’t feel shackled by previous iterations of the genre. Sophia Foster-Dimino’s “On Show Now,” the first story, not only looks great with its color scheme (black and white meets bright green), it has a smart extrapolation of existing technologies and fashions which are part of the world-building, but whose existence never overwhelms the story’s delicate probing of the protagonist’s inner life. In the story, a new dating app is used to convey the personality of potential dates by presenting virtual manifestations of personalities as art exhibits – showing the growing interconnectedness of art, self, and living spaces.

Likewise, Jonathan Djob-Nkondo’s “Between the Sun and the Tides” uses his free-flowing pencils and talent for atmosphere — he dedicates a full-page to a single wave rising in a beautiful shot that oscillates between the crushing power and beauty of nature — for a story about the passage of time and the nature of obsession. Both of these stories, and several more, show that a cyberpunk anthology can be more than a greatest hits album.

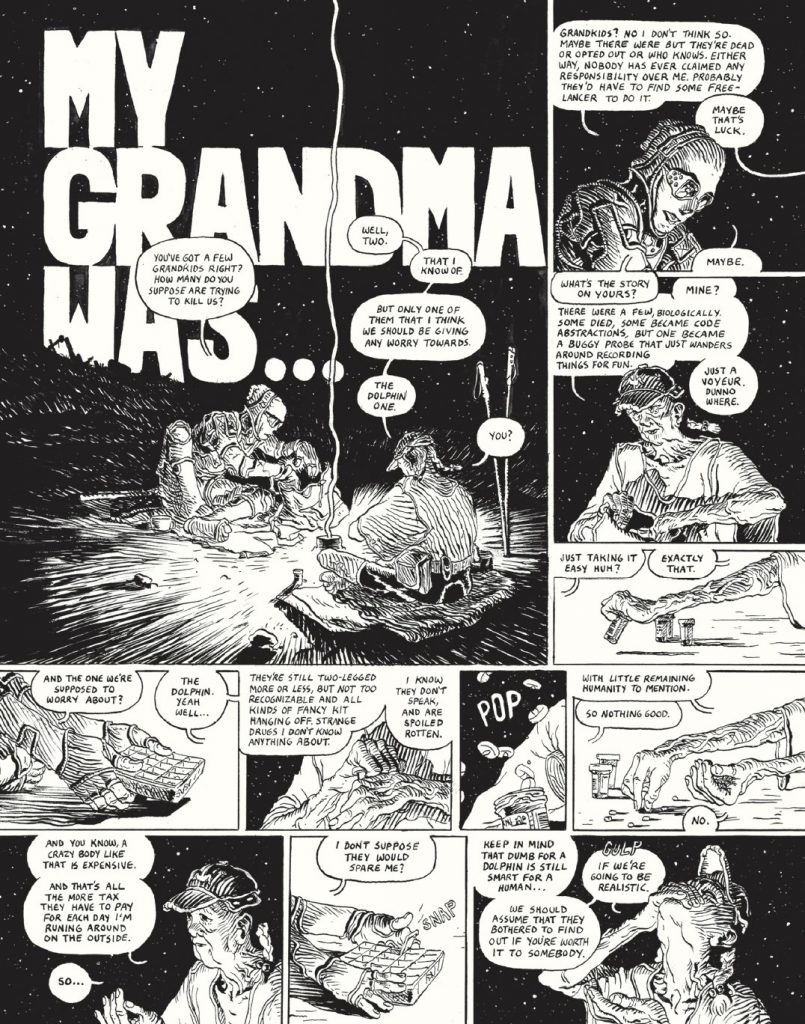

On the opposite side of the spectrum, McDonald’s own “Suncrest” and Milonogiannis’ “Polygon Bird” exist quite firmly within the established boundaries of the genre, both in terms of plot and design. Milonogiannis’ story even contains several scenes that utilize old 3D graphic designs for particularly retro-charm. Likewise, the short art pieces by Freddy Carrasco and Tonci Zonjic, both of which are better described as mood pieces rather than stories, evoke familiar images of cyber-bodies as wrecked futures. None of these are bad, and, whatever else you might say, they all look phenomenal, but compared to the previously mentioned expressive stories these fail to bring anything new to the table.

An anthology, especially a themed one, is not just a random assortment of stories. By his choice of stories, the way they are presented, even the order of publication – the editor is meant to tell us something. Ex.Mag #1 is a fine collection of tales, but it is not clear that it has a point of view about “cyberpunk” in general, and cyberpunk in 2020 in particular. Our present can be conceived as the nightmare those 1980s authors dreaded. We don’t have cyberspace, but we have social networks. We don’t have some anonymous Japanese corporation controlling governments, but Disney is gaining power every day. Mass surveillance has become the norm; though even the most cynical of those authors wouldn’t dream how easily we’d let the means of surveillance into our home. Ex.Mag #1 came out in 2020, but, in many ways, it feels like it could have been published a decade, or even two, ago. It seems odd to live in the now and see stories that still dream about the future with the visual language of Blade Runner and A Ghost in the Shell.

Jane Mai’s “Cyber Story 3049 by Michael C.” is the one story that directly challenges our notions of the genre. Granted, it does so via a one-note gag, but it’s a funny one-note gag. Plus, it’s short enough not to overstay its welcome. Still, the reader must ask – what does such a broad parody means in the context of the rest of the anthology? Ex.Mag #1 doesn’t need to be one thing, but it does need to know what it wants to be. As it stands, this is a grab bag of exploration, repetition, deconstruction, and absurdism without any clear point of view or natural progression. On their own, the stories here are worth your while, but the collection as a whole lacks the final finesse that would make it into a statement.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply